Ole Rømer facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Ole Rømer

|

|

|---|---|

Ole Rømer, portrait by Jacob Coning from c. 1700

|

|

| Born |

Ole Christensen Rømer

25 September 1644 |

| Died | 19 September 1710 (aged 65) |

| Nationality | Danish |

| Alma mater | University of Copenhagen |

| Known for | Rømer's determination of the speed of light Rømer scale Cycloid gear Light-time correction Altazimuth mount Meridian circle |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Astronomy |

| Signature | |

Ole Christensen Rømer (Danish: [ˈoːlə ˈʁœˀmɐ]; 25 September 1644 – 19 September 1710) was a Danish astronomer who, in 1676, made the first measurement of the speed of light.

Rømer also invented the modern thermometer showing the temperature between two fixed points, namely the points at which water respectively boils and freezes.

In scientific literature, alternative spellings such as "Roemer", "Römer", or "Romer" are common.

Contents

Biography

Rømer was born on 25 September 1644 in Århus to merchant and skipper Christen Pedersen (died 1663), and Anna Olufsdatter Storm (c. 1610 – 1690), daughter of a well-to-do alderman. Since 1642, Christen Pedersen had taken to using the name Rømer, which means that he was from the Danish island of Rømø, to distinguish himself from a couple of other people named Christen Pedersen. There are few records of Ole Rømer before 1662, when he graduated from the old Aarhus Katedralskole (the Cathedral school of Aarhus), moved to Copenhagen and matriculated at the University of Copenhagen. His mentor at the University was Rasmus Bartholin, who published his discovery of the double refraction of a light ray by Iceland spar (calcite) in 1668, while Rømer was living in his home. Rømer was given every opportunity to learn mathematics and astronomy using Tycho Brahe's astronomical observations, as Bartholin had been given the task of preparing them for publication.

Rømer was employed by the French government: Louis XIV made him tutor for the Dauphin, and he also took part in the construction of the magnificent fountains at Versailles.

In 1681, Rømer returned to Denmark and was appointed professor of astronomy at the University of Copenhagen, and the same year he married Anne Marie Bartholin, the daughter of Rasmus Bartholin. He was active also as an observer, both at the University Observatory at Rundetårn and in his home, using improved instruments of his own construction. Unfortunately, his observations have not survived: they were lost in the great Copenhagen Fire of 1728. However, a former assistant (and later an astronomer in his own right), Peder Horrebow, loyally described and wrote about Rømer's observations.

In Rømer's position as royal mathematician, he introduced the first national system for weights and measures in Denmark on 1 May 1683. Initially based on the Rhine foot, a more accurate national standard was adopted in 1698. Later measurements of the standards fabricated for length and volume show an excellent degree of accuracy. His goal was to achieve a definition based on astronomical constants, using a pendulum. This would happen after his death as practicalities made it too inaccurate at the time. Notable is also his definition of the new Danish mile of 24,000 Danish feet (circa 7,532 m).

In 1700, Rømer persuaded the king to introduce the Gregorian calendar in Denmark-Norway – something Tycho Brahe had argued for in vain a hundred years earlier.

Rømer developed one of the first temperature scales while convalescing from a broken leg. Daniel Gabriel Fahrenheit visited him in 1708 and altered the Rømer scale, the result being the familiar Fahrenheit temperature scale still in use today in a few countries.

Rømer also established navigation schools in several Danish cities.

In 1705, Rømer was made the second Chief of the Copenhagen Police, a position he kept until his death in 1710. As one of his first acts, he fired the entire force, being convinced that the morale was alarmingly low. He was the inventor of the first street lights (oil lamps) in Copenhagen, and worked hard to try to control the beggars, poor people, and unemployed of Copenhagen.

In Copenhagen, Rømer made rules for building new houses, got the city's water supply and sewers back in order, ensured that the city's fire department got new and better equipment, and was the moving force behind the planning and making of new pavement in the streets and on the city squares.

Rømer died at the age of 65 in 1710. He was buried in Copenhagen Cathedral, which has since been rebuilt following its destruction in the Battle of Copenhagen (1807). There is a modern memorial.

Rømer and the speed of light

The determination of longitude is a significant practical problem in cartography and navigation. Philip III of Spain offered a prize for a method to determine the longitude of a ship out of sight of land, and Galileo proposed a method of establishing the time of day, and thus longitude, based on the times of the eclipses of the moons of Jupiter, in essence using the Jovian system as a cosmic clock; this method was not significantly improved until accurate mechanical clocks were developed in the eighteenth century. Galileo proposed this method to the Spanish crown (1616–1617) but it proved to be impractical, because of the inaccuracies of Galileo's timetables and the difficulty of observing the eclipses on a ship. However, with refinements, the method could be made to work on land.

After studies in Copenhagen, Rømer joined Jean Picard in 1671 to observe about 140 eclipses of Jupiter's moon Io on the island of Hven at the former location of Tycho Brahe’s observatory of Uraniborg, near Copenhagen, over a period of several months, while in Paris Giovanni Domenico Cassini observed the same eclipses. By comparing the times of the eclipses, the difference in longitude of Paris to Uraniborg was calculated.

Cassini had observed the moons of Jupiter between 1666 and 1668, and discovered discrepancies in his measurements that, at first, he attributed to light having a finite speed. In 1672 Rømer went to Paris and continued observing the satellites of Jupiter as Cassini's assistant. Rømer added his own observations to Cassini's and observed that times between eclipses (particularly those of Io) got shorter as Earth approached Jupiter, and longer as Earth moved farther away.

Oddly, Cassini seems to have abandoned this reasoning, which Rømer adopted and set about buttressing in an irrefutable manner, using a selected number of observations performed by Picard and himself between 1671 and 1677. Rømer presented his results to the French Academy of Sciences, and it was summarised soon after by an anonymous reporter in a short paper, Démonstration touchant le mouvement de la lumière trouvé par M. Roemer de l'Académie des sciences, published 7 December 1676 in the Journal des sçavans. Unfortunately, the reporter, possibly in order to hide his lack of understanding, resorted to cryptic phrasing, obfuscating Rømer's reasoning in the process. Rømer himself never published his results.

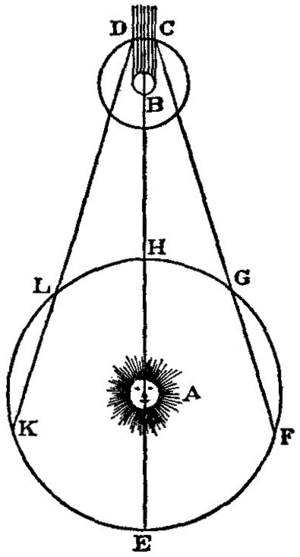

Rømer's reasoning was as follows. Referring to the illustration, assume the Earth is at point L, and Io emerges from Jupiter's shadow at point D. After several orbits of Io, at 42.5 hours per orbit, the Earth is at point K. If light is not propagated instantaneously, the additional time it takes to reach K, which he reckoned about 3½ minutes, would explain the observed delay. Rømer observed immersions at point C from positions F and G, to avoid confusion with eclipses (Io shadowed by Jupiter from C to D) and occultations (Io hidden behind Jupiter at various angles). In the table below, his observations in 1676, including the one on 7 August, believed to be at the opposition point H, and the one observed at Paris Observatory to be 10 minutes late, on 9 November.

| Month | Day | Time | Tide | orbits | average (hours) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| May | 12 | 2:49:42 | C | ||

| 2,837,189s | 18 | 41.48 | |||

| June | 13 | 22:56:11 | C | ||

| 4,748,019s | 31 | 42.54 | |||

| Aug | 7 | 21:49:50 | D | ||

| 611,765s | 4 | 42.48 | |||

| Aug | 14 | 23:45:55 | D | ||

| 764,718s | 5 | 42.48 | |||

| Aug | 23 | 20:11:13 | D | ||

| 6,729,872s | 44 | 42.49 | |||

| Nov | 9 | 17:35:45 | D | ||

By trial and error, during eight years of observations Rømer worked out how to account for the retardation of light when reckoning the ephemeris of Io. He calculated the delay as a proportion of the angle corresponding to a given Earth's position with respect to Jupiter, Δt = 22·(α⁄180°)[minutes]. When the angle α is 180° the delay becomes 22 minutes, which may be interpreted as the time necessary for the light to cross a distance equal to the diameter of the Earth's orbit, H to E. (Actually, Jupiter is not visible from the conjunction point E.) That interpretation makes it possible to calculate the strict result of Rømer's observations: The ratio of the speed of light to the speed with which Earth orbits the sun, which is the ratio of the duration of a year divided by pi as compared to the 22 minutes

365·24·60⁄π·22 ≈ 7,600.

In comparison, the modern value is circa 299,792 km s−1⁄29.8 km s−1 ≈ 10,100.

Rømer neither calculated this ratio, nor did he give a value for the speed of light. However, many others calculated a speed from his data, the first being Christiaan Huygens; after corresponding with Rømer and eliciting more data, Huygens deduced that light travelled 16+2⁄3 Earth diameters per second, which is approximately 212,000 km/s.

Rømer's view that the velocity of light was finite was not fully accepted until measurements of the so-called aberration of light were made by James Bradley in 1727.

In 1809, again making use of observations of Io, but this time with the benefit of more than a century of increasingly precise observations, the astronomer Jean Baptiste Joseph Delambre reported the time for light to travel from the Sun to the Earth as 8 minutes and 12 seconds. Depending on the value assumed for the astronomical unit, this yields the speed of light as just a little more than 300,000 kilometres per second. The modern value is 8 minutes and 19 seconds, and a speed of 299,792.458 km/s.

A plaque at the Observatory of Paris, where the Danish astronomer happened to be working, commemorates what was, in effect, the first measurement of a universal quantity made on this planet.

Inventions

In addition to inventing the first street lights in Copenhagen, Rømer also invented the meridian circle, the altazimuth, and the passage instrument (also known as the transit instrument, a type of meridian circle whose horizontal axis is not fixed in the east-west direction).

Ole Rømer Medal

The Ole Rømer Medal is given annually by the Danish Natural Science Research Council for outstanding research.

The Ole Rømer Museum

The Ole Rømer Museum is located in the municipality of Høje-Taastrup, Denmark, at the excavated site of Rømer's observatory Observatorium Tusculanum at Vridsløsemagle. The observatory opened in 1704, and operated until about 1716, when the remaining instruments were moved to Rundetårn in Copenhagen. There is a large collection of ancient and more recent astronomical instruments on display at the museum. The museum opened in 1979, and has since 2002 been a part of the museum Kroppedal at the same location.

Honours

In Denmark, Ole Rømer has been honoured in various ways through the ages. He has been portrayed on bank notes, the eponymous Ole Rømer's Hill is named after him, as are streets in both Aarhus and Copenhagen (Ole Rømers Gade and Rømersgade respectively). Aarhus University's astronomical observatory is named The Ole Rømer Observatory (Ole Rømer Observatoriet) in his honour, and a Danish satellite project to measure the age, temperature, physical and chemical conditions of selected stars, was named The Rømer Satellite. The satellite project stranded in 2002 and was never realised though.

The Römer crater on the Moon is named after him.

See also

In Spanish: Ole Rømer para niños

In Spanish: Ole Rømer para niños