Nilgai facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Nilgai |

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Boselaphus tragocamelus | |

| Conservation status | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | |

| Phylum: | |

| Class: | |

| Order: | |

| Family: | |

| Subfamily: | |

| Genus: |

Boselaphus

|

| Species: |

B. tragocamelus

|

| Binomial name | |

| Boselaphus tragocamelus Pall., 1766

|

|

The Nilgai (Boselaphus tragocamelus) is an antelope.

It is one of the most commonly seen wild animals of northern India and eastern Pakistan. The mature males appear ox-like and are also known as Blue bulls. The nilgai is the biggest Asian antelope.

Contents

Description

The nilgai is the largest antelope in Asia. It stands 1–1.5 metres (3.3–4.9 ft) at the shoulder; the head-and-body length is typically between 1.7–2.1 metres (5.6–6.9 ft). Males weigh 109–288 kilograms (240–635 lb); the maximum weight recorded is 308 kilograms (679 lb). Females are lighter, weighing 100–213 kilograms (220–470 lb). Sexual dimorphism is prominent; the males are larger than females and differ in colouration.

A sturdy thin-legged antelope, the nilgai is characterised by a sloping back, a deep neck with a white patch on the throat, a short mane of hair behind and along the back ending behind the shoulder, and around two white spots each on its face, ears, cheeks, lips and chin. The ears, tipped with black, are 15–18 centimetres (5.9–7.1 in) long. A column of coarse hair, known as the "pendant" and around 13 centimetres (5.1 in) long in males, can be observed along the dewlap ridge below the white throat patch. The tufted tail, up to 54 centimetres (21 in), has a few white spots and is tipped with black. The forelegs are generally longer, and the legs are often marked with white "socks".

While females and juveniles are orange to tawny, males are much darker – their coat is typically bluish grey. The ventral parts, the insides of the thighs and the tail are all white. A white stripe extends from the underbelly and broadens as it approaches the rump, forming a patch lined with dark hair. Almost white, though not albino, individuals have been observed in the Sariska National Park (Rajasthan, India) while individuals with white patches have been recorded at zoos. The hairs, typically 23–28 centimetres (9.1–11.0 in) long, are fragile and brittle. Males have thicker skin on their head and neck that protect them in fights. The coat is not well-insulated with fat during winter, and consequently severe cold might be fatal for the nilgai.

Only males possess horns, though a few females may be horned as well. The horns are 15–24 centimetres (5.9–9.4 in) long but generally shorter than 30 centimetres (12 in). Smooth and straight, these may point backward or forward. The horns of the nilgai and the four-horned antelope lack the ringed structure typical of those of other bovids.

The maximum recorded length of the skull is 376 millimetres (14.8 in). The dental formula is 0.0.3.33.1.3.3. The milk teeth are totally lost and the permanent dentition completed by three years of age. The permanent teeth get degraded with age, showing prominent signs of wear at six years of age. The nilgai has sharp ears and eyes, though its sense of smell is not as acute.

Ecology and behavior

The nilgai is diurnal (active mainly during the day). A 1991 study investigated the daily routine of the antelope and found feeding peaks at dawn, in the morning, in the afternoon and during the evening. Females and juveniles do not interact appreciably with males, except during the mating season. Groups are generally small, with ten or fewer individuals, though groups of 20 to 70 individuals can occur at times. In a 1980 study in the Bardiya National Park (Nepal), the average herd size was of three individuals; In a 1995 study in the Gir National Park (Gujarat, India), herd membership varied with season. However, three distinct groupings are formed: one or two females with young calves, three to six adult and yearling females with calves, and male groups with two to 18 members.

Typically tame, the nilgai may appear timid and cautious if harassed or alarmed; instead of seeking cover like duikers it would flee up to 300 metres (980 ft)-or even 700 metres (2,300 ft) on galloping-away from the danger. Though generally quiet, nilgai have been reported to make short guttural grunts when alarmed, and females to make clicking noises when nursing young. Alarmed individuals, mainly juveniles below five months, give out a coughing roar (whose pitch is highest in case of the juveniles) that lasts half a second, but can be heard by herds less than 500 metres (1,600 ft) away and responded to similarly.

In India, the nilgai shares its habitat with the four-horned antelope, chinkara, chital and blackbuck; its association with the gaur and the water buffalo is less common. In the Ranthambore National Park (Rajasthan, India) the nilgai and the chinkara collectively prefer the area rich in Acacia and Butea species, while the sambar deer and the chital preferred the forests of Anogeissus and Grewia species. In India, the Indian tiger and the lion may prey on the nilgai but they are not significant predators of this antelope. Leopards prey on the nilgai, though they prefer smaller prey. Dholes generally attack juveniles. Other predators include wolves and striped hyenas.

Diet

Herbivores, the nilgai prefer grasses and herbs; woody plants are commonly eaten in the dry tropical forests of India. Studies suggest they may be browsers or mixed feeders in India, whereas they are primarily grazers in Texas. The nilgai can tolerate interference by livestock and degradation of vegetation in its habitat better than deer, possibly because they can reach high branches and do not depend on surface vegetation. The sambar deer and nilgai in Nepal have similar dietary preferences. Diets generally suffice in protein and fats. The protein content of the nilgai's should be at least seven percent. The nilgai can survive for long periods without water and do not drink regularly even in summer. However, a nilgai died in Dwarka (India) allegedly due to the heat wave and acute shortage of water.

Reproduction

Gestation lasts eight to nine months, following which a single calf or twins (even triplets at times) are born. In a 2004 study in the Sariska reserve, twins accounted for as high as 80 percent of the total calf population. Births peak from June to October in the Bharatpur National Park, and from April to August in southern Texas. Calves are precocial; they are able to stand within 40 minutes of birth, and forage by the fourth week. Pregnant females isolate themselves before giving birth. As typical of several bovid species, nilgai calves are kept in hiding for the first few weeks of their lives. This period of concealment can last as long as a month in Texas. Calves, mainly males, bicker playfully by neck-fighting. Young males would leave their mothers at ten months to join bachelor groups. The lifespan of the nilgai is typically ten years in Texas.

Habitat and distribution

Nilgai prefer areas with short bushes and scattered trees in scrub forests and grassy plains. They are common in agricultural lands, but hardly occur in dense woods. In southern Texas, it roams in the prairies, scrub forests and oak forests. It is a generalist animal-it can adapt to a variety of habitats. Though sedentary and less dependent on water, nilgai may desert their territories if all water sources in and around it dry up. Territories in Texas are 0.6 to 8.1 square kilometres (0.23 to 3.13 sq mi) large.

This antelope is endemic to the Indian subcontinent: major populations occur in India, Nepal and Pakistan, whereas it is extinct in Bangladesh. Significant numbers occur in the Terai lowlands in the foothills of the Himalayas; the antelope is abundant across northern India. The Indian population was estimated at one million in 2001. The nilgai were first introduced to Texas in the 1920s and the 1930s in a 6,000 acres (2,400 ha) large ranch near the Norias Division of the King Ranch, one of the largest ranches in the world. The feral population saw a spurt toward the latter part of the 1940s, and gradually spread out to adjoining ranches.

Population densities show great geographical variation across India. Density can be as low as 0.23 to 0.34 individuals per km2 in the Indravati National Park (Chhattisgarh) and 0.4 individuals per km2 in the Pench Tiger Reserve (Madhya Pradesh) or as high as 6.60 to 11.36 individuals per km2 and Ranthambhore National Park and 7 individuals per km2 in Keoladeo National Park (both in Rajasthan). Seasonal variations were noted in the Bardiya National Park (Nepal) in a 1980 study; the density 3.2 individuals per km2 during the dry season and 5 per km2 in April (the start of the dry season). In southern Texas, densities were found to be nearly 3–5 individuals per km2 in 1976.

Images for kids

-

Nilgai in the Gir National Park, Gujarat (India)

-

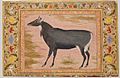

Nilgai illustrated by Ustad Mansur for Jahangir (1605–27), c. 1620

See also

In Spanish: Nilgó para niños

In Spanish: Nilgó para niños