Montgomery Bus Boycott facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Montgomery bus boycott |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Civil Rights Movement | |||

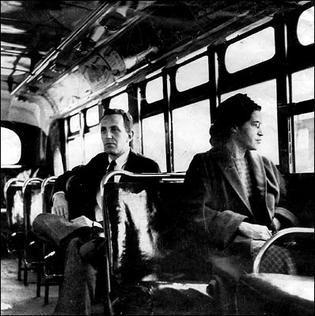

Rosa Parks on a Montgomery bus on December 21, 1956, the day Montgomery's public transportation system was legally integrated. Behind Parks is Nicholas C. Chriss, a UPI reporter covering the event.

|

|||

| Date | December 5, 1955 – December 20 , 1956 | ||

| Location |

Montgomery, Alabama, U.S.

|

||

| Caused by |

|

||

| Resulted in |

|

||

| Parties to the civil conflict | |||

|

|||

| Lead figures | |||

|

|||

The Montgomery Bus Boycott was a major event in the Civil Rights Movement. It occurred in Montgomery, Alabama where the city buses were segregated. Black passengers were required by law to ride in the back of the bus. On December 1, 1955 Rosa Parks, an African American woman, refused to give her bus seat to a white person. She was arrested and sent to jail. In protest about 40,000 black people boycotted the Montgomery city buses, refusing to ride. The boycott lasted 381 days. On November 13, 1956, the United States Supreme Court issued its decision to desegregate the buses. In response the city of Montgomery passed a law allowing black passengers to sit anywhere on the buses. The boycott ended on December 20, 1956. Many important people in the civil rights movement took part in the boycott. This included Reverend Martin Luther King, Jr. and Ralph Abernathy.

Contents

History

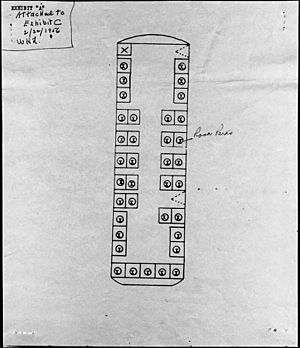

Under the system of segregation used on Montgomery buses, the ten front seats were reserved for white people at all times. The ten back seats were supposed to be reserved for black people at all times. The middle section of the bus consisted of sixteen unreserved seats for white and black people on a segregated basis. White people filled the middle seats from the front to back, and black people filled seats from the back to front until the bus was full. If other black people boarded the bus, they were required to stand. If another white person boarded the bus, then everyone in the black row nearest the front had to get up and stand so that a new row for white people could be created; it was illegal for white and black people to sit next to each other. When Rosa Parks refused to give up her seat for a white person, she was sitting in the first row of the middle section.

Often when boarding the buses, black people were required to pay at the front, get off, and reenter the bus through a separate door at the back. Occasionally, bus drivers would drive away before black passengers were able to reboard. National City Lines owned the Montgomery Bus Line at the time of the Montgomery bus boycott. Under the leadership of Walter Reuther, the United Auto Workers donated almost $5,000 (equivalent to $55,000 in 2022) to the boycott's organizing committee.

Rosa Parks

Rosa Parks (February 4, 1913 – October 24, 2005) was a seamstress by profession; she was also the secretary for the Montgomery chapter of the NAACP. Twelve years before her history-making arrest, Parks was stopped from boarding a city bus by driver James F. Blake, who ordered her to board at the rear door and then drove off without her. Parks vowed never again to ride a bus driven by Blake.

In 1955, Parks completed a course in "Race Relations" at the Highlander Folk School in Tennessee, where nonviolent civil disobedience had been discussed as a tactic. On December 1, 1955, Parks was sitting in the foremost row in which black people could sit (in the middle section). When a white man boarded the bus, the bus driver told everyone in her row to move back. At that moment, Parks realized that she was again on a bus driven by Blake. While all of the other black people in her row complied, Parks refused, and she was arrested for failing to obey the driver's seat assignments, as city ordinances did not explicitly mandate segregation but did give the bus driver authority to assign seats. Found guilty on December 5, Parks was fined $10 plus a court cost of $4 (combined total equivalent to $153 in 2022), and she appealed.

E. D. Nixon

Some action against segregation had been in the works for some time before Parks' arrest, under the leadership of E. D. Nixon, president of the local NAACP chapter and a member of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters. Nixon intended that her arrest be a test case to allow Montgomery's black citizens to challenge segregation on the city's public buses. With this goal, community leaders had been waiting for the right person to be arrested, a person who would anger the black community into action, who would agree to test the segregation laws in court, and who, most importantly, was "above reproach". When Colvin was arrested in March 1955, Nixon thought he had found the perfect person, but the teenager turned out to be pregnant. Nixon later explained, "I had to be sure that I had somebody I could win with." Parks was a good candidate because of her employment and marital status, along with her good standing in the community.

Between Parks' arrest and trial, Nixon organized a meeting of local ministers at Martin Luther King Jr.'s church. Though Nixon could not attend the meeting because of his work schedule, he arranged that no election of a leader for the proposed boycott would take place until his return. When he returned, he caucused with Ralph Abernathy and Rev. E.N. French to name the association to lead the boycott to the city (they selected the "Montgomery Improvement Association", "MIA"), and they selected King (Nixon's choice) to lead the boycott. Nixon wanted King to lead the boycott because the young minister was new to Montgomery and the city fathers had not had time to intimidate him. At a subsequent, larger meeting of ministers, Nixon's agenda was threatened by the clergymen's reluctance to support the campaign. Nixon was indignant, pointing out that their poor congregations worked to put money into the collection plates so these ministers could live well, and when those congregations needed the clergy to stand up for them, those comfortable ministers refused to do so. Nixon threatened to reveal the ministers' cowardice to the black community, and King spoke up, denying he was afraid to support the boycott. King agreed to lead the MIA, and Nixon was elected its treasurer.

Boycott

On the night of Rosa Parks' arrest, the Women's Political Council, led by Jo Ann Robinson, printed and circulated a flyer throughout Montgomery's black community that read as follows:

Another woman has been arrested and thrown in jail because she refused to get up out of her seat on the bus for a white person to sit down. It is the second time since the Claudette Colvin case that a Negro woman has been arrested for the same thing. This has to be stopped. Negroes have rights too, for if Negroes did not ride the buses, they could not operate. Three-fourths of the riders are Negro, yet we are arrested, or have to stand over empty seats. If we do not do something to stop these arrests, they will continue. The next time it may be you, or your daughter, or mother. This woman's case will come up on Monday. We are, therefore, asking every Negro to stay off the buses Monday in protest of the arrest and trial. Don't ride the buses to work, to town, to school, or anywhere on Monday. You can afford to stay out of school for one day if you have no other way to go except by bus. You can also afford to stay out of town for one day. If you work, take a cab, or walk. But please, children and grown-ups, don't ride the bus at all on Monday. Please stay off all buses Monday.

The next morning there was a meeting led by the new Montgomery Improvement Association (MIA) head, King, where a group of 16 to 18 people gathered at the Mt. Zion Church to discuss boycott strategies. At that time Rosa Parks was introduced but not asked to speak, despite a standing ovation and calls from the crowd for her to speak; she asked someone if she should say something, but they replied, "Why, you've said enough." A citywide boycott of public transit was proposed, with three demands: 1) courteous treatment by bus operators, 2) passengers seated on a first-come, first-served basis, with black people seated in the back half and white people seated in the front half, and 3) black people would be employed as bus operators on routes predominately taken by black people.

This demand was a compromise for the leaders of the boycott, who believed that the city of Montgomery would be more likely to accept it rather than a demand for full integration of the buses. In this respect, the MIA leaders followed the pattern of 1950s boycott campaigns in the Deep South, including the successful boycott a few years earlier of service stations in Mississippi for refusing to provide restrooms for Black people.

The MIA's demand for a fixed dividing line was to be supplemented by a requirement that all bus passengers receive courteous treatment by bus operators, be seated on a first-come, first-served basis, and that Black people be employed as bus drivers. The proposal was passed, and the boycott was to commence the following Monday. To publicize the impending boycott it was advertised at black churches throughout Montgomery the following Sunday.

On Saturday, December 3, it was evident that the black community would support the boycott, and very few Black people rode the buses that day. On December 5, a mass meeting was held at the Holt Street Baptist Church to determine if the protest would continue. Given twenty minutes notice, King gave a speech asking for a bus boycott and attendees enthusiastically agreed. Starting December 7, J Edgar Hoover's FBI noted the "agitation among negroes" and tried to find "derogatory information" about King.

The boycott proved extremely effective, with enough riders lost to the city transit system to cause serious economic distress. Martin Luther King later wrote, "[a] miracle had taken place." Instead of riding buses, boycotters organized a system of carpools, with car owners volunteering their vehicles or themselves driving people to various destinations. Some white housewives also drove their black domestic servants to work. When the city pressured local insurance companies to stop insuring cars used in the carpools, the boycott leaders arranged policies at Lloyd's of London.

Black taxi drivers charged ten cents per ride, a fare equal to the cost to ride the bus, in support of the boycott. When word of this reached city officials on December 8, the order went out to fine any cab driver who charged a rider less than 45 cents. In addition to using private motor vehicles, some people used non-motorized means to get around, such as cycling, walking, or even riding mules or driving horse-drawn buggies. Some people also hitchhiked. During rush hours, sidewalks were often crowded. As the buses received few, if any, passengers, their officials asked the City Commission to allow stopping service to black communities. Across the nation, black churches raised money to support the boycott and collected new and slightly used shoes to replace the tattered footwear of Montgomery's black citizens, many of whom walked everywhere rather than ride the buses and submit to Jim Crow laws.

In response, opposing whites swelled the ranks of the White Citizens' Council, the membership of which doubled during the course of the boycott. The councils sometimes resorted to violence: King's and Abernathy's houses were firebombed, as were four black Baptist churches. Boycotters were often physically attacked. After the attack at King's house, he gave a speech to the 300 angry African Americans who had gathered outside. He said:

If you have weapons, take them home; if you do not have them, please do not seek to get them. We cannot solve this problem through retaliatory violence. We must meet violence with nonviolence. Remember the words of Jesus: "He who lives by the sword will perish by the sword". We must love our white brothers, no matter what they do to us. We must make them know that we love them. Jesus still cries out in words that echo across the centuries: "Love your enemies; bless them that curse you; pray for them that despitefully use you". This is what we must live by. We must meet hate with love. Remember, if I am stopped, this movement will not stop, because God is with the movement. Go home with this glowing faith and this radiant assurance.

King and 88 other boycott leaders and carpool drivers were indicted for conspiring to interfere with a business under a 1921 ordinance. Rather than wait to be arrested, they turned themselves in as an act of defiance.

King was ordered to pay a $500 fine or serve 386 days in jail. He ended up spending two weeks in jail. The move backfired by bringing national attention to the protest. King commented on the arrest by saying: "I was proud of my crime. It was the crime of joining my people in a nonviolent protest against injustice."

Also important during the bus boycott were grassroots activist groups that helped to catalyze both fund-raising and morale. Groups such as the Club from Nowhere helped to sustain the boycott by finding new ways of raising money and offering support to boycott participants. Many members of these organizations were women and their contributions to the effort have been described by some as essential to the success of the bus boycott.

Victory

Pressure increased across the country. The related civil suit was heard in federal district court and, on June 5, 1956, the court ruled in Browder v. Gayle (1956) that Alabama's racial segregation laws for buses were unconstitutional. As the state appealed the decision, the boycott continued. The case moved on to the United States Supreme Court. On November 13, 1956, the Supreme Court upheld the district court's ruling.

The bus boycott officially ended on December 20, 1956, after 382 days, with Day 1 being December 5, 1955. The Montgomery bus boycott resounded far beyond the desegregation of public buses. It stimulated activism and participation from the South in the national Civil Rights Movement and gave King national attention as a rising leader.

See also

In Spanish: Boicot de autobuses de Montgomery para niños

In Spanish: Boicot de autobuses de Montgomery para niños