Citizens' Councils facts for kids

Citizens' Councils logo

|

|

| Abbreviation | WCC |

|---|---|

| Successor | Council of Conservative Citizens |

| Formation | July 11, 1954 |

| Type | NGO |

| Purpose | Maintaining segregation and white supremacy in the South. |

|

Membership

|

60,000 (1955) |

|

Founder

|

Robert B. Patterson |

The Citizens' Councils (commonly referred to as the White Citizens' Councils) were an associated network of white supremacist, segregationist organizations in the United States, concentrated in the South and created as part of a white backlash against the US Supreme Court's landmark Brown v. Board of Education ruling. The first was formed on July 11, 1954. The name was changed to the Citizens' Councils of America in 1956. With about 60,000 members across the Southern United States, the groups were founded primarily to oppose racial integration of public schools: the logical conclusion of the Brown v. Board of Education ruling.

The Councils also worked to oppose voter registration efforts in the South (where most African Americans had been disenfranchised since the late 19th century) and integration of public facilities in general during the 1950s and 1960s. Members employed tactics such as economic boycotts, unjustified termination of employment, propaganda, and outright violence. By the 1970s the influence of the Councils had waned considerably due to the passage of federal civil rights legislation. The councils' mailing lists and some of their board members found their way to the St. Louis–based Council of Conservative Citizens, founded in 1985.

Contents

History

Founding and activities

In May 1954, the US Supreme Court ruled in Brown v. Board of Education that the segregation of public schools was unconstitutional. At the time, schools and other public facilities were segregated by state laws in Southern states. The Citizens' Councils were founded in Indianola, Mississippi two months after the Brown v. Board ruling. The recognized leader was Robert B. Patterson, a plantation manager and a former captain of the Mississippi State University football team. Additional chapters were established in many other southern towns in following years.

At this time, most Southern states enforced the racial segregation of all public facilities; in places where local laws did not require segregation, Jim Crow harassment enforced it. From 1890 to 1908, most Southern states passed new constitutions or laws which disfranchised most blacks by imposing barriers to voter registration and voting. Despite the fact that civil rights organizations won some legal challenges, such as the prohibition on white primaries, most blacks were still disfranchised in the South in the 1950s. They risked retaliation by challenging the segregation of seating on buses as well as the segregation of seating at lunch counters, including segregation in department stores. The risks did not end immediately after the passage of the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

Patterson and his followers formed the White Citizens Council in response to increased civil rights activism, activism which it responded to with economic retaliation and violence. The Regional Council of Negro Leadership (RCNL), a grassroots civil rights organization founded in 1951 by T. R. M. Howard of the all-black town Mound Bayou, Mississippi, was based 40 miles from Indianola. Aaron Henry, a later official in the RCNL and the future head of the Mississippi NAACP had met Patterson during their childhood.

Within a few months, the White Citizens Council had attracted members whose racist views were similar to the views of its leaders; new chapters developed beyond Mississippi in the rest of the Deep South. The Council often had the support of the leading white citizens of many communities, including business, law enforcement, civic and sometimes religious leaders, many of whom were members. Member businesses, such as newspaper publishing, legal representation, medical service, were known for collectively acting against registered voters whose names were first published in local papers before additional retaliatory actions were taken against them.

Racist ideology

Council members published a book which was titled Black Monday. The book detailed their belief that African Americans were inferior to white people which served as the basis for their belief that the races must remain separate. "If in one mighty voice we do not protest this travesty on justice, we might as well surrender," one of the authors, Mississippi Circuit Court Judge Tom P. Brady, wrote.

Extension outside the South

In August 1956, their official newspaper reported councils in "at least 30 states" in places such as Chicago, Cleveland, Detroit, Los Angeles, St. Louis and Newark.

In 1964, the Councils published two advertisements in the newspapers of several cities, the first claiming that Lincoln was a segregationist and the second citing Thomas Jefferson's quotes claiming that "nature, habit, opinion have drawn indelible lines of distinction between" both races.

As a result, interest for the Councils in the Pacific Northwest and Missouri emerged. Likewise, the 1964 George Wallace campaign created interest in Indiana and Wisconsin. Two full-time organizers were named to create councils outside the Deep South: former John Birch Society staff member Kent H. Steffgen was named for California, where the recent riots created interest for the Councils, and Joseph McDowell Mitchell, the actor of the "Battle of Newburgh", was named for Virginia, Maryland and Washington.

Demise and reconstitution

By the 1970s, as white Southerners' attitudes towards desegregation began to change following the passage of federal civil rights legislation and the enforcement of integration and voting rights in the 1960s, the activities of the White Citizens' Councils began to wane. The Council of Conservative Citizens, founded in 1985 by former White Citizens' Council members, continued the agendas of the earlier Councils.

Activities

Publishing and broadcasting

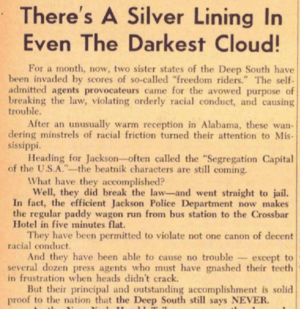

Unlike the secretive Ku Klux Klan but working in unison, the White Citizens Council met openly. It was seen superficially as "pursuing the agenda of the Klan with the demeanor of the Rotary Club". From October 1954, the council published a newsletter, The Citizens' Council, which evolved into a magazine in October 1961 and continued to be published until 1989 as The Citizen.

From 1957 to 1966, the Citizens' Council had a broadcast program, The Citizens Forum, where they exposed their doctrine of segregation. First broadcast by the WLBT as a television program, it switched to a radio format and was broadcast from Washington, DC, using congressional studios with the help of people like Eastland. Various personalities such as Eastland or John Bell Williams were interviewed there. From 1966, they did emissions from African countries such as Rhodesia, interviewing Ian Smith.

Among its other activities, throughout the last half of the 1950s, the White Citizens' Councils produced racist children's books, for instance, teaching that heaven (in the Christian conception) is segregated.

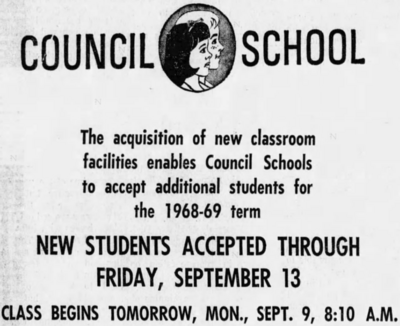

Council Schools

The White Citizens' Council in Mississippi prevented school integration until 1964. As school desegregation increased in some parts of the South, in some communities the White Citizens' Council sponsored "council schools," private institutions set up for white children. Such private schools, also called segregation academies, were beyond the reach of the ruling on public schools. Many of these private "segregation academies" continue to operate today.

The Council sponsored a system of twelve segregated schools in Jackson, Mississippi.

Voter suppression

Citizens' Councils conducted voter purges to remove Black voters from election rolls.

Before the practice was found illegal in a federal court case of 1963, the Council pushed a public challenge law allowing two voters to challenge another voter to see if he was lawfully registered, a provision they used to purge the rolls of Black voters. In one parish, Bienville Parish, 95% of Black voters were purged. Similarly, the Council distributed such pamphlets as "Voter Qualification Laws in Louisiana: The Key to Victory in the Segregation Struggle" to white registrars and required them to participate in mandatory seminars about preventing Black registration and purging Black voters.

Political influence

Many leading state and local politicians were members of the Councils; in some states, this gave the organization immense influence over state legislatures. In Mississippi, the State Sovereignty Commission was established, ostensibly to encourage investment in the state and promote its public image. Although funded by taxes paid by all state residents, it made grants to the segregationist Citizens' Councils, in some years providing as much as $50,000. This state agency also shared information with the Councils that it had collected through its secret police-type investigations and surveillance of integration activists. For example, Dr. M. Ney Williams was both a director of the Citizens' Council and an adviser to governor Ross Barnett of Mississippi.

Barnett was a member of the council, as was Jackson mayor Allen C. Thompson. In 1955, in the midst of the bus boycott seeking integration of seating on city buses, all three members of the Montgomery city commission in Alabama announced on television that they had joined the Citizens' Council.

Numan Bartley wrote, "In Louisiana the Citizens' Council organization began as (and to a large extent remained) a projection of the Joint Legislative Committee to Maintain Segregation." In Louisiana, leaders of the original Citizens' Council included State Senator and gubernatorial candidate William M. Rainach, U.S. Representative Joe D. Waggonner Jr., the publisher Ned Touchstone, and Judge Leander Perez, considered the political boss of Plaquemines and St. Bernard parishes near New Orleans.

On July 16, 1956, "under pressure from the White Citizens Councils," the Louisiana State Legislature passed a law mandating racial segregation in nearly every aspect of public life; much of the segregation already existed under Jim Crow custom. The bill was signed into law by governor Earl Long on July 16, 1956, and went into effect on October 15, 1956.

The act read, in part:

An Act to prohibit all interracial dancing, social functions, entertainments, athletic training, games, sports, or contests and other such activities; to provide for separate seating and other facilities for white and negroes [lower case in original] ... That all persons, firms, and corporations are prohibited from sponsoring, arranging, participating in or permitting on premises under their control ... such activities involving personal and social contact in which the participants are members of the white and negro races ... That white persons are prohibited from sitting in or using any part of seating arrangements and sanitary or other facilities set apart for members of the negro race. That negro persons are prohibited from sitting in or using any part of seating arrangements and sanitary or other facilities set apart for white persons.

In 1964, the Councils' membership was said to be nearly all supporting Barry Goldwater.

Major media outlets observed the support George Wallace received from groups such as White Citizens' Councils. It has been noted that members of such groups had permeated the Wallace campaign by 1968 and, while Wallace did not openly seek their support, he did not refuse it.

See also

In Spanish: Citizens' Council para niños

In Spanish: Citizens' Council para niños

- Racism in the United States

- Racism against Black Americans

- Civil Rights Movement

- States' rights