Medieval Jerusalem facts for kids

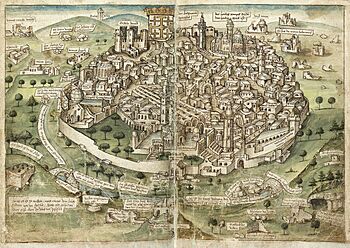

Jerusalem in the Middle Ages was a major Byzantine metropolis from the 4th century CE before the advent on the early Islamic period in the 7th century saw it become the regional capital of Jund Filastin under successive caliphates. In the later Islamic period it went on to experience a period of more contested ownership, war and decline. Muslim rule was interrupted for a period of about 200 years by the Crusades and the establishment of the Christian Kingdom of Jerusalem. At the tail end of the Medieval period, the city was ceded to the Ottomans in 1517, who maintained control of it until the British took it in 1917.

Jerusalem prospered during both the Byzantine period and in the early time period, but under the rule of the Fatimid caliphate beginning in the late 10th century saw its population decrease from about 200,000 to less than half that number by the time of the Christian conquest in 1099. The siege of Jerusalem by the Crusaders saw much of the extant population at the time massacred as the Christian invaders took the city, and while its population quickly recovered during the Kingdom of Jerusalem, its population was decimated to less than 2,000 people when the Khwarezmi Turks took the city in 1244. The city remained a backwater under the Ayyubids, Mameluks and Ottomans, and would not again exceed a population of 10,000 until the 16th century.

Contents

- Terminology

- Byzantine rule

- Early Muslim period (637/38–1099)

- Crusader control

- Khwarezmian control

- Ayyubid control

- Mamluk control and Mongol raids

- Mamluk rebuilding

- Ottoman era

- See also

Terminology

The term Middle Ages (in other words: the medieval period) in regard to the history of Jerusalem, is defined by archaeologists such as S. Weksler-Bdolah as the time span consisting of the 12th and 13th centuries.

Byzantine rule

Jerusalem reached a peak in size and population at the end of the Second Temple period: The city covered two square kilometers (0.8 sq mi.) and had a population of 200,000. In the five centuries following the Bar Kokhba revolt in the 2nd century, the city remained under Roman then Byzantine rule. During the 4th century, the Roman Emperor Constantine I constructed Christian sites in Jerusalem such as the Church of the Holy Sepulchre.

John Cassian, a Christian monk and theologian who spent several years in Bethlehem during the late 4th century, wrote that 'Jerusalem can be taken in four senses: historically as the city of the Jews; allegorically as 'Church of Christ', analogically as the heavenly city of God 'which is the mother of us all,' topologically, as the soul of man".

In 603, Pope Gregory I commissioned the Ravennate Abbot Probus, who was previously Gregory's emissary at the Lombard court, to build a hospital in Jerusalem to treat and care for Christian pilgrims to the Holy Land. In 800, Charlemagne enlarged Probus' hospital and added a library to it, but it was destroyed in 1005 by Al-Hakim bi-Amr Allah along with three thousand other buildings in Jerusalem.

From the days of Constantine until the Arab conquest in 637/38, despite intensive lobbying by Judeo-Byzantines, Jews were forbidden to enter the city. Following the Arab capture of Jerusalem, the Jews were allowed back into the city by Muslim rulers such as Umar ibn al-Khattab. During the 8th to 11th centuries, Jerusalem's prominence gradually diminished as the Arab powers in the region jockeyed for control.

Early Muslim period (637/38–1099)

Rashidun period (630s–661)

Domination of the countryside

Southern Palestine was conquered by the Muslims under the commander Amr ibn al-As following their decisive victory over the Byzantines at the Battle of Ajnadayn, likely fought at a site about 25 kilometers (16 mi) south-southwest of Jerusalem, in 634. Although Jerusalem remained unoccupied, the 634 Christmas sermon of Patriarch Sophronius of Jerusalem indicated that the Muslim Arabs were in control of the city's environs by then, as the Patriarch was unable to travel to nearby Bethlehem for the ritual Feast of the Nativity due to the presence of Arab raiders. According to one reconstruction of the Islamic tradition, a Muslim advance force was sent against Jerusalem by Amr ibn al-As on his way to Ajnadayn. By 635 southern Syria was in Muslim hands, except for Jerusalem and the Byzantines' capital of Palestine, Caesarea. In his homily of the Theophany (Orthodox Epiphany), c. 636–637, Sophronius lamented the killings, raids, and destruction of churches by the Arabs.

Siege and capitulation

It is unclear when Jerusalem was precisely captured, but most modern sources place it in the spring of 637. In that year the troops of Abu Ubayda ibn al-Jarrah, head commander of the Muslim forces in Syria, besieged the city. History Records Caliph Umar (r. 634 – 644), who was headquartered in Medina, made one or several visits to Jabiya, the Muslims' principal camp in Syria, in 637–638. The modern historians Fred Donner and Hugh N. Kennedy assess that he came to address multiple administrative matters in the newly conquered province. While in Jabiya, Umar negotiated Jerusalem's surrender with a delegation from the city, as the Patriarch insisted on surrendering to the Caliph directly rather than his commanders.

The earliest known Muslim tradition of Jerusalem's capture was cited in the history of al-Baladhuri (d. 892) and credits the Arab commander Khalid ibn Thabit al-Fahmi for arranging the city's capitulation with terms guaranteeing Muslim domination of the countryside and safeguarding the city's inhabitants in return for tributary payment. Khalid ibn Thabit had been dispatched by Umar from Jabiya. The historian Shelomo Dov Goitein considered this tradition to be the most reliable narrative of Jerusalem's capture. Another account, that contained in the histories of al-Ya'qubi (d. 898) and Eutychius of Alexandria (d. 940), holds that a treaty was agreed between the Muslims and Jerusalem's inhabitants, though the terms were largely the same as those cited by al-Baladhuri. The 10th-century history of al-Tabari, citing the 8th-century historian Sayf ibn Umar, reproduces the capitulation agreement in detail, though parts of it may have been altered from the time it was made. Although Goitein considered Sayf's account "worthless" on account of Sayf's general unreliability, the historians Moshe Gil and Milka Levy-Rubin have argued that the tradition was largely authentic. The agreement for Jerusalem was generally favorable for the city's Christian inhabitants, guaranteeing the safety of their persons, their property, and churches, and allowing them the freedom of worship in return for payment of the jizya (poll tax). Byzantine troops and other residents seeking to evacuate the city were given security assurances from the time they left Jerusalem until they reached their point of departure from Palestine. Gil assessed that Umar adopted a lenient approach so that the inhabitants could continue their way of life and work and thus be able to subsidize the Arab tribesmen garrisoned in Palestine.

The treaty cited in al-Tabari, and later Christian sources, contained a stipulation barring Jewish residency alongside the city's Christians, a continuation of a ban started in the days of Emperor Hadrian (r. 117 – 138) and renewed in the days of Emperor Constantine (r. 306 – 337). Among them was the history of Michael the Syrian (d. 1199), who wrote that Sophronius negotiated the ban on Jews residing in Jerusalem. (see below).

Several later Muslim and Christians accounts, as well as an 11th-century Jewish chronicle, mention a visit to Jerusalem by Umar. One set of accounts held that Umar was guided by Jews who showed him the Temple Mount. In the Muslim and Jewish accounts, a prominent Jewish convert to Islam, Ka'b al-Ahbar, recommended that Umar pray behind the Holy Rock so that both qiblas (direction point of Islamic prayer) lay behind him. Umar rejected the suggestion, insisting that the Ka'aba in Mecca was the sole qibla; Jerusalem had been the original qibla of the early Muslims until Muhammad changed it to the Ka'aba. The Muslim and Jewish sources reported that the Temple Mount was cleaned by the Muslims of the city and its district and a group of Jews. The Jewish account further noted that Umar oversaw the process and consulted with Jewish elders; Gil suggests the Jewish elders may be a reference to Ka'b al-Ahbar. The Christian accounts mentioned that Umar visited Jerusalem's churches, but refused to pray in them to avoid setting a precedent for future Muslims. This tradition may have been originated by later Christian writers to promote efforts against Muslim encroachments on their holy places.

Post-conquest administration and settlement

Jerusalem is presumed by Goitein and the historian Amikam Elad to have been the Muslims' main political and religious center in Jund Filastin (district of Palestine) from the conquest until the foundation of Ramla at the beginning of the 8th century. It may have been preceded by the Muslims' principal military camp at Emmaus Nicopolis before this was abandoned due to the Plague of Amwas in 639. The historian Nimrod Luz, on the other hand, holds that the early Muslim tradition indicates Palestine from the time of Umar had dual capitals at Jerusalem and Lydda, each city having its own governor and garrison. An auxiliary force of tribesmen from Yemen was posted in the city during this period. Amr ibn al-As launched the conquest of Egypt from Jerusalem in c. 640, and his son Abd Allah transmitted hadiths about the city.

Christian leadership in Jerusalem entered a state of disorganization following the death of Sophronius c. 638, with no new patriarch appointed until 702. Nonetheless, Jerusalem remained largely Christian in character throughout the early Islamic period. Not long after the conquest, possibly in 641, Umar allowed a limited number of Jews to reside in Jerusalem after negotiations with the Christian leadership of the city. An 11th-century Jewish chronicle fragment from the Cairo Geniza indicated that the Jews requested the settlement of two hundred families, the Christians would only accept fifty, and that Umar ultimately decided on the settlement of seventy families from Tiberias. Gil attributed the Caliph's move to his recognition of the Jews' local importance, by dint of their considerable presence and economic strength in Palestine, as well as a desire to weaken Christian dominance of Jerusalem.

At the time of the conquest, the Temple Mount had been in a state of ruin, the Byzantine Christians having left it largely unused for scriptural reasons. The Muslims appropriated the site for administrative and religious purposes. This was likely due to a range of factors. Among them was that the Temple Mount was a large, unoccupied space in Jerusalem, where the Muslims were restricted by the capitulation terms from confiscating Christian-owned property in the city. Jewish converts to Islam may have also influenced the early Muslims regarding the site's holiness, and the early Muslims may have wanted to demonstrate their opposition to the Christian belief that the Temple Mount should remain empty. Moreover, the early Muslims may have had a spiritual attachment to the site before the conquest. Their utilization of the Temple Mount provided a vast space for the Muslims overlooking the whole city. The Temple Mount was likely used for Muslim prayer from the beginning of Muslim rule, due to the capitulation agreement's prohibitions on Muslims using Christian edifices. Such usage of the Temple Mount may have been authorized by Umar. The traditions cited by the 11th-century Jerusalemites al-Wasiti and Ibn al-Murajja note that Jews were employed as caretakers and cleaners of the Temple Mount and the ones employed were exempt from the jizya.

The earliest Muslim settlement activity took place south and southwest of the site, in thinly populated areas; much of the Christian settlement was concentrated in western Jerusalem around Golgotha and Mount Zion. The first Muslim settlers in Jerusalem hailed mainly from the Ansar, i.e. the people of Medina. They included Shaddad ibn Aws, nephew of the prominent companion of Muhammad and poet Hassan ibn Thabit. Shaddad died and was buried in Jerusalem between 662 and 679. His family remained prominent there, and his tomb later became a place of veneration. Another prominent companion, the Ansarite commander Ubada ibn al-Samit, also settled in Jerusalem where he became the city's first qadi (Islamic judge). The father of Muhammad's Jewish concubine Rayhana and a Jewish convert from Medina, Sham'un (Simon), settled in Jerusalem and, according to Mujir al-Din, delivered Muslim sermons on the Temple Mount. Umm al-Darda, an Ansarite and the wife of the first qadi of Damascus, resided in Jerusalem for half of the year. Umar's successor Caliph Uthman (r. 644 – 656) was said by the 10th-century Jerusalemite geographer al-Muqaddasi to have earmarked the revenues of Silwan's bountiful vegetable gardens on the city's outskirts, which would have been Muslim property per the capitulation terms, to the city's poor.

Umayyad period (661–750)

Sufyanid period (661–684)

Caliph Mu'awiya ibn Abi Sufyan (r. 661 – 680), the founder of the Umayyad Caliphate, originally served as the governor of Syria under Umar and Uthman. He opposed Uthman's successor Ali during the First Muslim Civi War and forged a pact against him with the former governor of Egypt and conqueror of Palestine, Amr ibn al-As, in Jerusalem in 658.

According to the near-contemporary Maronite Chronicle and Islamic traditional accounts, Mu'awiya obtained oaths of allegiance as caliph in Jerusalem on at least two different occasions between 660 and July 661. Although the precise dating is inconsistent, the Muslim and non-Muslim accounts generally agree that the oaths to Mu'awiya took place at a mosque on the Temple Mount. The mosque may have been erected by Umar and expanded by Mu'awiya, though there are no apparent traces of the structure today. The Maronite Chronicle notes that "many emirs and Tayyaye [Arab nomads] gathered [at Jerusalem] and proffered their right hand[s] to Mu'awiya". Afterward, he sat and prayed at Golgotha and then prayed at Mary's Tomb in Gethsemane. The "Arab nomads" were likely the indigenous Arab tribesmen of Syria, most of whom had converted to Christianity under the Byzantines and many of whom had retained their Christian faith during the early decades of Islamic rule. Mu'awiya's prayer at Christian sites was out of respect for the Syrian Arabs, who were the foundation of his power. His advisers Sarjun ibn Mansur and Ubayd Allah ibn Aws the Ghassanid may have helped organize the Jerusalem ceremonies.

Mu'awiya's son and successor to the caliphate, Yazid I (r. 680 – 683), may have visited Jerusalem on several occasions during his lifetime. The historian Irfan Shahid theorizes that the visits, in the company of the prominent Arab Christian poet al-Akhtal, were attempts to promote his own legitimacy as caliph among the Muslims.

Marwanid period (684–750)

The Umayyad caliph Abd al-Malik (r. 685 – 705), who had served as the governor of Jund Filastin under his father Caliph Marwan I (r. 684 – 685), received his oaths of allegiance in Jerusalem. From the beginning of his caliphate, Abd al-Malik began plans for the construction of the Dome of the Rock and the al-Aqsa Mosque, both located on the Temple Mount. The Dome of the Rock was completed in 691–692, constituting the first great work of Islamic architecture. The Dome of the Rock's construction was supervised by the Caliph's theological adviser Raja ibn Haywa of Beisan and his Jerusalemite mawla (non-Arab convert to Islam) Yazid ibn Salam. The construction of the Dome of the Chain on the Temple Mount is generally credited to Abd al-Malik.

Abd al-Malik and his practical viceroy over Iraq, al-Hajjaj ibn Yusuf, are credited by the Islamic tradition for constructing two gates of the Temple Mount, which Elad proposes are the Prophet's Gate and the Mercy Gate; both are attributed to the Umayyads by modern scholars. The Caliph repaired the roads connecting his capital Damascus with Palestine and linking Jerusalem to its eastern and western hinterlands. The roadworks are evidenced by seven milestones found throughout the region, the oldest of which dates to May 692 and the latest to September 704. The milestones, all containing inscriptions crediting Abd al-Malik, were found, from north to south, in or near Fiq, Samakh, St. George's Monastery of Wadi Qelt, Khan al-Hathrura, Bab al-Wad and Abu Ghosh. The fragment of an eighth milestone, likely produced soon after Abd al-Malik's death, was found at Ein Hemed, immediately west of Abu Ghosh. The road project formed part of the Caliph's centralization drive, special attention being paid to Palestine due to its critical position as a transit zone between Syria and Egypt and Jerusalem's religious centrality to the Caliph.

Extensive building works took place on the Temple Mount and outside of its walls under Abd al-Malik's son and successor al-Walid I (r. 705 – 715). Modern historians generally credit al-Walid with the construction of the al-Aqsa Mosque on the Temple Mount, though the mosque may have been originally built by his Umayyad predecessors; according to the latter view, al-Walid was nonetheless responsible for part of the mosque's construction. The Aphrodito Papyri indicate that laborers from Egypt were sent to Jerusalem for terms ranging between six months and one year to work on the al-Aqsa Mosque, al-Walid's caliphal palace, and a third, undefined building for the Caliph. Elad holds that the six Umayyad buildings excavated south and west of the Temple Mount may include the palace and undefined building mentioned in the papyri.

Al-Walid's brother and successor Sulayman (r. 715 – 717), who had served as the governor of Jund Filastin under al-Walid and Abd al-Malik, was initially recognized as caliph in Jerusalem by the Arab tribes and dignitaries. He resided in Jerusalem for an unspecified period during his caliphate, and his contemporary, the poet al-Farazdaq, may have alluded to this in the verse "In the Mosque al-Aqsa resides the Imam [Sulayman]". He constructed a bathhouse there, but may not have shared the same adoration for Jerusalem as his predecessors. Sulayman's construction of a new city, Ramla, located about 40 kilometres (25 mi) northwest of Jerusalem, came at Jerusalem's expense in the long-term, as Ramla developed into Jund Filastin's administrative and economic capital.

According to the Byzantine historian Theophanes the Confessor (d. 818), Jerusalem's walls were destroyed by the last Umayyad caliph, Marwan II, in 745. At that time, the Caliph had suppressed the Arab tribes in Palestine opposed to him for joining the revolt of the Umayyad prince Sulayman ibn Hisham in northern Syria.

Muslim pilgrimage and rituals in the Umayyad period

Under the Umayyads the focus of Muslim ritual ceremonies and pilgrimage in Jerusalem was the Temple Mount and to a lesser extent the Prayer Niche of David (possibly the Tower of David), the Spring of Silwan, the Garden of Gethsemane and Mary's Tomb, and the Mount of Olives. The Umayyads encouraged Muslim pilgrimage and prayer in Jerusalem and traditions originated during the Umayyad period celebrated the city. During this period, Muslim pilgrims came to Jerusalem to sanctify themselves before making the Umra or Hajj pilgrimages to Mecca. Muslims who could not make the pilgrimage, and possibly Christians and Jews, donated olive oil for the illumination of the al-Aqsa Mosque. The bulk of the Muslim pilgrims to Jerusalem were presumably from Palestine and Syria in general, though several came from distant parts of the Caliphate.

Abbasids, Tulunids and Ikhshidids (750–969)

The Umayyads were toppled in 750 by the Abbasid dynasty, which afterward ruled the Caliphate including Jerusalem, with interruptions, for the next two centuries. This period is the least documented of the early Muslim period in general. Known building activity was concentrated in the Temple Mount area and was characterized by repairs of structures damaged in earthqauakes. The caliphs al-Mansur (r. 754 – 775) and al-Mahdi (r. 775 – 785) ordered major reconstruction of the al-Aqsa Mosque after earthquake damage.

After the first Abbasid period (750–878), the Tulunids, a mamluk dynasty of Turkic origin, managed to independently rule over Egypt and much of Greater Syria, including Palestine, for almost three decades (878–905). Ahmad ibn Tulun, the founder of the Egypt-based dynasty, consolidated his rule over Palestine between 878 and 880 and passed it on to his son at his death in 884. According to Patriarch Elias III of Jerusalem, Ibn Tulun finished a period of persecution against Christians by naming a Christian governor in Ramla (or perhaps Jerusalem), the governor initiating the renovation of churches in the city. Ibn Tulun had a Jewish physician and generally showed a very relaxed attitude towards dhimmis, and when he lay on his deathbed, both Jews and Christians prayed for him. Ibn Tulun was the first in a line of Egypt-based rulers of Palestine, which ended with the Ikhshidids. While the Tulunids managed to preserve a high degree of autonomy, the Abbasids retook control over Jerusalem in 905, and between 935 and 969 it was administered by their Egyptian governors, the Ikhshidids. During this entire period, Jerusalem's religious importance grew, several of the Egyptian rulers choosing to be buried there.

Abbasid rule returned between 905 and 969, the first 30 years of which was direct rule from Baghdad (905–935), and the rest was through the Ikhshidid governors of Egypt (935–969). The mother of Caliph al-Muqtadir (r. 908 – 932) had wooden porches built under all the city gates and repaired the Dome of the Rock.

The Ikhshidid period was characterised by acts of persecution against the Christians, including an attack by the Muslims on the Church of the Holy Sepulchre in 937, with the church set on fire and its treasure robbed. The tensions were connected with the renewed threat posed by the encroaching Byzantines, and on this background the Jews joined forces with the Muslims. In 966 the Muslim and Jewish mob, instigated by the Ikhshidid governor, attacked again the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, the resulting fire causing the collapse of the dome standing over the Tomb of Jesus and causing the death of Patriarch John VII.

Fatimids and Seljuks (970–1099)

The start of the first Fatimid period (970–1071) saw a predominantly Berber army conquer the region. After six decades of war and another four of relative stability, Turkish tribes invade the region, starting off a period of permanent upheaval, fighting against each other and the Fatimids and, in less than thirty years of warfare and vandalism, destroyed much of Palestine, bringing terrible hardships, particularly on the Jewish population. However, the Jewish communities stayed in their places, only to be uprooted after 1099 by the Crusaders. Turkish rule totalled more than a quarter of a century of constant warfare, negatively affecting the local Christian communities, as well as eventually blocking the access of pilgrims from Europe, which is seen as a factor in initiating the Crusades. We know however also about a visitor from Muslim Spain, who left us a report about the intense activity in Jerusalem's Sunni madrasas and his interaction with Jews and Christians in the years 1093–95.

Between 1071 and 1076, Palestine was captured by Turkman or Turcoman tribes, with Jerusalem falling in 1073. The Turcomans acted in the region as free agents, but became known as Seljuqs, after the primary rulers among the Turkish invaders of the Arab Muslim realm, the Seljuk dynasty, whom they were associated with. Seljuk emir Atsiz ibn Uvaq al-Khwarizmi, leader of the Turkic tribe of the Nawaki, besieged and captured Jerusalem in 1073 and held it for four years. Atsiz placed the territory he captured under the nominal control of the 'Abbasid caliphate. In 1077, on his return from a disastrous attempt to capture Cairo, the capital of the Fatimid caliphate, he found that in his absence the inhabitants of Jerusalem had rebelled and forced his garrison to shelter in the citadel, capturing the families and property of the Turcomans. Atsiz besieged Jerusalem and promised the defenders the aman, pardon and safety, at which they surrendered. Atsiz broke his promise and slaughtered 3000 inhabitants, including those who had taken shelter in the Al-Aqsa Mosque and only sparing those inside the Dome of the Rock. In 1079, Atsiz was murdered by his nominal ally Tutush, who subsequently established firmer 'Abbasid authority in the area. After Atsiz other Seljuk commanders ruled over Jerusalem and used it as a power base in their unceasing wars. A new period of turbulence began in 1091 with the death of Tutush's governor in Jerusalem, Artuq and the succession of his two sons, who were bitter rivals. The city changed hands between them several times, until August 1098, when the Fatimids, seizing the opportunity presented by the approach of the First Crusade, regained control of the city and ruled it for a less than a year.

Crusader control

Reports of the renewed killing of Christian pilgrims, and the defeat of the Byzantine Empire by the Seljuqs, led to the First Crusade. Europeans marched to recover the Holy Land, and on July 15, 1099, Christian soldiers were victorious in the one-month Siege of Jerusalem. In keeping with their alliance with the Muslims, the Jews had been among the most vigorous defenders of Jerusalem against the Crusaders. When the city fell, the Crusaders slaughtered most of the city's Muslim and Jewish inhabitants, leaving the city "knee deep in blood".

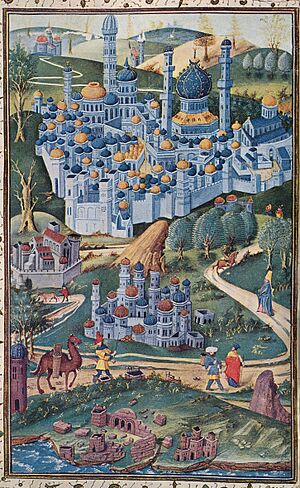

Jerusalem became the capital of the Kingdom of Jerusalem. Christian settlers from the West set about rebuilding the principal shrines associated with the life of Christ. The Church of the Holy Sepulchre was ambitiously rebuilt as a great Romanesque church, and Muslim shrines on the Temple Mount (the Dome of the Rock and the Al-Aqsa Mosque) were converted for Christian purposes. The Military Orders of the Knights Hospitaller and the Knights Templar were established during this period. Both grew out of the need to protect and care for the great influx of pilgrims traveling to Jerusalem, especially since Bedouin enslavement raids and terror attacks upon the roads by the remaining Muslim population continued. King Baldwin II of Jerusalem allowed the forming order of the Templars to set up a headquarters in the captured Al-Aqsa Mosque. The Crusaders believed the Mosque to have been built on top of the ruins of the Temple of Solomon (or rather his royal palace), and therefore referred to the Mosque as "Solomon's Temple", in Latin "Templum Solomonis". It was from this location that the Order took its name of "Temple Knights" or "Templars".

Under the Kingdom of Jerusalem the area experienced a great revival, including the re-establishment of the city and harbour of Caesarea, the restoration and fortification of the city of Tiberias, the expansion of the city of Ashkelon, the walling and rebuilding of Jaffa, the reconstruction of Bethlehem, the repopulation of dozens of towns, the restoration of large agriculture, and the construction of hundreds of churches, cathedrals, and castles. The old hospice, rebuilt in 1023 on the site of the monastery of Saint John the Baptist, was expanded into an infirmary under Hospitaller grand master Raymond du Puy de Provence near the Church of the Holy Sepulchre.

In 1173 Benjamin of Tudela visited Jerusalem. He described it as a small city full of Jacobites, Armenians, Greeks, and Georgians. Two hundred Jews dwelt in a corner of the city under the Tower of David.

In 1187, with the Muslim world united under the effective leadership of Saladin, Jerusalem was re-conquered by the Muslims after a successful siege. As part of this same campaign the armies of Saladin conquered, expelled, enslaved, or killed the remaining Christian communities of Galilee, Samaria, Judea, as well as the coastal towns of Ashkelon, Jaffa, Caesarea, and Acre.

In 1219 the walls of the city were razed by order of Al-Mu'azzam, the Ayyubid sultan of Damascus. This rendered Jerusalem defenseless and dealt a heavy blow to the city's status.

Following another Crusade by the Holy Roman Emperor Frederick II in 1227, the city was surrendered by Saladin's descendant al-Kamil, in accordance with a diplomatic treaty in 1228. It remained under Christian control, under the treaty's terms that no walls or fortifications could be built in the city or along the strip which united it with the coast. In 1239, after the ten-year truce expired, Frederick ordered the rebuilding of the walls. But without the formidable Crusader army he had originally employed ten years previous, his goals were effectively thwarted when the walls were again demolished by an-Nasir Da'ud, the emir of Kerak, in the same year.

In 1243 Jerusalem was firmly secured into the power of the Christian Kingdom, and the walls were repaired. However, the period was extremely brief as a large army of Turkish and Persian Muslims was advancing from the north.

Khwarezmian control

Jerusalem fell again in 1244 to the Khwarazmian Empire, who had been displaced by the Mongol invasion of Khwarazm. As the Khwarezmians moved west, they allied with the Egyptians, under the Egyptian Ayyubid sultan as-Salih Ayyub. He recruited his horsemen from the Khwarezmians and directed the remains of the Khwarezmian Empire into the Levant, where he wanted to organize a strong defense against the Mongols.

In keeping with his goal, the main effect of the Khwarezmians was to slaughter the local population, especially in Jerusalem. Their Siege of Jerusalem began on July 11, 1244, and the city's citadel, the so-called Tower of David, surrendered on August 23. The Khwarezmians then ruthlessly decimated the population, leaving only 2,000 people, Christians and Muslims, still living in the city. This attack triggered the Europeans to respond with the Seventh Crusade, although the new forces of King Louis IX of France never even achieved success in Egypt, let alone advancing as far as Palestine.

Ayyubid control

After having troubles with the Khwarezmians, Sultan as-Salih began ordering armed expeditions to raid Christian communities and capture men, women and children. Called razzias, or by their original Arabic name ghazw (sing.: ghazwa or ghaza), the raids extended into Caucasia, the Black Sea, Byzantium, and the coastal areas of Europe.

The newly enslaved were divided according to category. Women were turned into maids. The men depending upon age and ability were made into servants or killed. Young boys and girls were sent to imams, where they were indoctrinated into Islam. According to ability the young boys were then made into eunuchs or sent into decades-long training as mamluk (slave soldiers). This army of indoctrinated slaves was forged into a potent armed force. The Sultan then used this new army to eliminate the Khwarezmians, and Jerusalem returned to Ayyubid rule in 1247.

Mamluk control and Mongol raids

When al-Salih died, his widow, the slave Shajar al-Durr, took power as Sultana, which power she then transferred to the Mamluk leader Aybeg, who became Sultan in 1250. Meanwhile, the Christian rulers of Antioch and Cilician Armenia subjected their territories to Mongol authority, and fought alongside the Mongols during the Empire's expansion into Iraq and Syria. In 1260, a portion of the Mongol army advanced toward Egypt, and was engaged by the Mamluks in Galilee, at the pivotal Battle of Ain Jalut. The Mamluks were victorious, and the Mongols retreated. In early 1300, there were again some Mongol raids into the southern Levant, shortly after the Mongols had been successful in capturing cities in northern Syria; however, the Mongols occupied the area for only a few weeks, and then retreated again to Iran. The Mamluks regrouped and re-asserted control over the southern Levant a few months later, with little resistance.

There is little evidence to indicate whether or not the Mongol raids penetrated Jerusalem in either 1260 or 1300. Historical reports from the time period tend to conflict, depending on which nationality of historian was writing the report. There were also a large number of rumors and urban legends in Europe, claiming that the Mongols had captured Jerusalem and were going to return it to the Crusaders. However, these rumors turned out to be false. The general consensus of modern historians is that though Jerusalem may or may not have been subject to raids, that there was never any attempt by the Mongols to incorporate Jerusalem into their administrative system, which is what would be necessary to deem a territory "conquered" as opposed to "raided".

Mamluk rebuilding

Even during the conflicts, pilgrims continued to come in small numbers. Pope Nicholas IV negotiated an agreement with the Mamluk sultan to allow Latin clergy to serve in the Church of the Holy Sepulchre. With the Sultan's agreement, Pope Nicholas, a Franciscan himself, sent a group of friars to keep the Latin liturgy going in Jerusalem. With the city little more than a backwater, they had no formal quarters, and simply lived in a pilgrim hostel, until in 1300 King Robert of Sicily gave a large gift of money to the Sultan. Robert asked that the Franciscans be allowed to have the Sion Church, the Mary Chapel in the Holy Sepulchre, and the Nativity Cave, and the Sultan gave his permission. But the remainder of the Christian holy places were kept in decay.

Mamluk sultans made a point of visiting the city, endowing new buildings, encouraging Muslim settlement, and expanding mosques. During the reign of Sultan Baibars, the Mamluks renewed the Muslim alliance with the Jews and he established two new sanctuaries, one to Moses near Jericho and one to Salih near Ramla, to encourage numerous Muslim and Jewish pilgrims to be in the area at the same time as the Christians, who filled the city during Easter. In 1267 Nahmanides (also known as Ramban) made aliyah. In the Old City he established the Ramban Synagogue, the oldest active synagogue in Jerusalem. However, the city had no great political power, and was in fact considered by the Mamluks as a place of exile for out-of-favor officials. The city itself was ruled by a low-ranking emir.

Following the persecutions of Jews during the Black Death, a group of Ashkenazi Jews led by Rabbi Isaac Asir HaTikvah immigrated to Jerusalem and founded a yeshiva. This group was part of the nucleus of what later became a much larger community in the Ottoman period.

Ottoman era

In 1517, Jerusalem and its environs fell to the Ottoman Turks, who would maintain control of the city until the 20th century. Although the Europeans no longer controlled any territory in the Holy Land, Christian presence including Europeans remained in Jerusalem. During the Ottomans this presence increased as Greeks under Turkish Sultan patronage re-established, restored, or reconstructed Orthodox Churches, hospitals, and communities. This era saw the first expansion outside the Old City walls, as new neighborhoods were established to relieve the overcrowding that had become so prevalent. The first of these new neighborhoods included the Russian Compound and the Jewish Mishkenot Sha'ananim, both founded in 1860.

See also

- Aelia Capitolina

- Demographic history of Jerusalem

- Kingdom of Jerusalem

- Old City of Jerusalem