Malcolm X facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Malcolm X

|

|

|---|---|

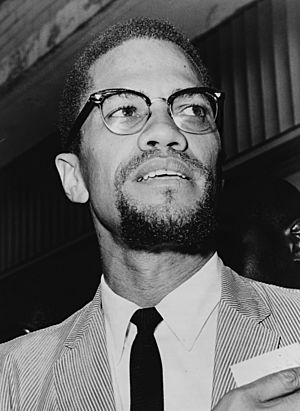

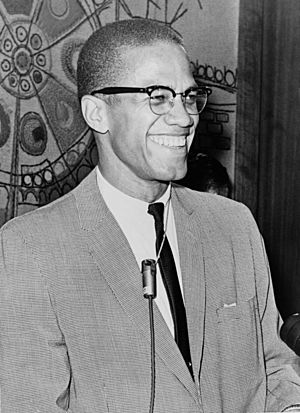

Malcolm X in March 1964

|

|

| Born |

Malcolm Little

May 19, 1925 |

| Died | February 21, 1965 (aged 39) New York City, U.S.

|

| Cause of death | Assassination (multiple gunshots) |

| Resting place | Ferncliff Cemetery |

| Other names | el-Hajj Malik el-Shabazz (الحاجّ مالك الشباز) |

| Occupation | Minister, activist |

| Organization | Nation of Islam, Muslim Mosque, Inc., Organization of Afro-American Unity |

| Height | 6 ft 3 in (191 cm) |

| Movement | Black nationalism, Pan-Africanism |

| Spouse(s) | Betty Shabazz (m. 1958) |

| Children | Attallah Shabazz Qubilah Shabazz Ilyasah Shabazz Gamilah Lumumba Shabazz Malikah Shabazz Malaak Shabazz |

| Parent(s) | Earl Little, Louise Helen Norton Little |

| Signature | |

|

|

Malcolm X (born Malcolm Little, later Malik el-Shabazz; May 19, 1925 – February 21, 1965) was an American Muslim minister and human rights activist who was a prominent figure during the civil rights movement. A spokesman for the Nation of Islam until 1964, he was a vocal advocate for Black empowerment and the promotion of Islam within the Black community.

Contents

Early years

Malcolm X was born May 19, 1925, in Omaha, Nebraska, the fourth of seven children of Grenada-born Louise Helen Little (née Norton) and Georgia-born Earl Little. Earl was an outspoken Baptist lay speaker, and he and Louise were admirers of Pan-African activist Marcus Garvey. Earl was a local leader of the Universal Negro Improvement Association (UNIA) and Louise served as secretary and "branch reporter".

Because of Ku Klux Klan threats, Earl's UNIA activities were said to be "spreading trouble" and the family relocated in 1926 to Milwaukee, and shortly thereafter to Lansing, Michigan. There, the family was frequently harassed by the Black Legion, a White racist group Earl accused of burning their family home in 1929.

When Malcolm was six, his father died. To make ends meet, Louise rented out part of her garden, and her sons hunted game.

In 1938, Louise had a nervous breakdown and was committed to Kalamazoo State Hospital. The children were separated and sent to foster homes.

Malcolm attended West Junior High School in Lansing and then Mason High School in Mason, Michigan, but left high school in 1941, before graduating. He excelled in junior high school but dropped out of high school.

From age 14 to 21, Malcolm held a variety of jobs while living with his half-sister Ella Little-Collins in Roxbury, a largely African-American neighborhood of Boston.

After a short time in Flint, Michigan, he moved to New York City's Harlem neighborhood in 1943, where he found employment on the New Haven Railroad.

In 1946, Little was put in prison for burglary and discovered the Nation of Islam while he was there.

Activism

From his adoption of the Nation of Islam in 1952 until he broke with it in 1964, Malcolm X promoted the Nation's teachings. These included beliefs:

- that Black people are the original people of the world

- that White people are "devils" and

- that the demise of the White race is imminent.

Malcolm X was critical of the civil rights movement. While the civil rights movement fought against racial segregation, Malcolm X advocated the complete separation of African Americans from Whites. He proposed that African Americans should return to Africa and that, in the interim, a separate country for Black people in America should be created. He rejected the civil rights movement's strategy of nonviolence, arguing that Black people should defend and advance themselves "by any means necessary". His speeches had a powerful effect on his audiences, who were generally African Americans in northern and western cities. Many of them—tired of being told to wait for freedom, justice, equality and respect—felt that he articulated their complaints better than did the civil rights movement.

Malcolm X is widely regarded as the second most influential leader of the Nation of Islam after Elijah Muhammad. He was largely credited with the group's dramatic increase in membership between the early 1950s and early 1960s (from 500 to 25,000 by one estimate; from 1,200 to 50,000 or 75,000 by another).

On March 8, 1964, Malcolm X publicly announced his break from the Nation of Islam. Though still a Muslim, he felt that the Nation had "gone as far as it can" because of its rigid teachings. He said he was planning to organize a Black nationalist organization to "heighten the political consciousness" of African Americans. He also expressed a desire to work with other civil rights leaders.

After leaving the Nation of Islam, Malcolm X founded Muslim Mosque, Inc. (MMI), a religious organization, and the Organization of Afro-American Unity (OAAU), a secular group that advocated Pan-Africanism. On March 26, 1964, he briefly met Martin Luther King Jr. for the first and only time—and only long enough for photographs to be taken—in Washington, D.C., as both men attended the Senate's debate on the Civil Rights bill at the US Capitol building.

In April, Malcolm X gave a speech titled "The Ballot or the Bullet", in which he advised African Americans to exercise their right to vote wisely but cautioned that if the government continued to prevent African Americans from attaining full equality, it might be necessary for them to take up arms.

Death

Malcolm X was shot dead in New York City after preaching about black rights. Three members of the Nation of Islam had a part in his murder.

Personal life

In 1955, Betty Sanders met Malcolm X after one of his lectures, then again at a dinner party; soon she was regularly attending his lectures. In 1956, she joined the Nation of Islam, changing her name to Betty X. One-on-one dates were contrary to the Nation's teachings, so the couple courted at social events with dozens or hundreds of others, and Malcolm X made a point of inviting her on the frequent group visits he led to New York City's museums and libraries.

Malcolm X proposed during a telephone call from Detroit in January 1958, and they married two days later. They had six daughters: Attallah (b. 1958; Arabic for "gift of God"; perhaps named after Attila the Hun); Qubilah (b. 1960, named after Kublai Khan); Ilyasah (b. 1962, named after Elijah Muhammad); Gamilah Lumumba (b. 1964, named after Gamal Abdel Nasser and Patrice Lumumba); and twins Malikah (1965–2021) and Malaak (b. 1965, both born after their father's death, and named in his honor).

Legacy

Malcolm X has been described as one of the greatest and most influential African Americans in history. He is credited with raising the self-esteem of Black Americans and reconnecting them with their African heritage. He is largely responsible for the spread of Islam in the Black community in the United States. Many African Americans, especially those who lived in cities in the Northern and Western United States, felt that Malcolm X articulated their complaints concerning inequality better than did the mainstream civil rights movement. One biographer says that by giving expression to their frustration, Malcolm X "made clear the price that White America would have to pay if it did not accede to Black America's legitimate demands."

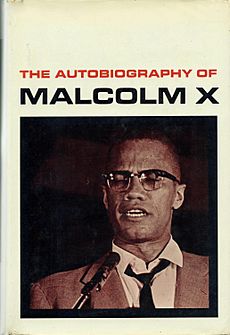

In the late 1960s, increasingly radical Black activists based their movements largely on Malcolm X and his teachings. The Black Power movement, the Black Arts Movement, and the widespread adoption of the slogan "Black is beautiful" can all trace their roots to Malcolm X. In 1963, Malcolm X began a collaboration with Alex Haley on his life story, The Autobiography of Malcolm X. He told Haley, "If I'm alive when this book comes out, it will be a miracle." Haley completed and published it some months after the assassination.

During the late 1980s and early 1990s, there was a resurgence of interest in his life among young people. Hip-hop groups such as Public Enemy adopted Malcolm X as an icon, and his image was displayed in hundreds of thousands of homes, offices, and schools, as well as on T-shirts and jackets. In 1986 Ella Little-Collins merged the Organization of Afro-American Unity with the African American Defense League.

In 1992 the film Malcolm X, an adaptation of The Autobiography of Malcolm X, was released,. In 1998, Time named The Autobiography of Malcolm X one of the ten most influential nonfiction books of the 20th century.

Malcolm X was an inspiration for several fictional characters. He was fictionalized as the character Minister Q in the 1967 novel The Man Who Cried I Am by John A. Williams. The Marvel Comics writer Chris Claremont confirmed that Malcolm X was an inspiration for the X-Men character Magneto, while Martin Luther King was an inspiration for Professor X. Malcolm X also inspired the character Erik Killmonger in the film Black Panther.

Memorials and tributes

The house that once stood at 3448 Pinkney Street in North Omaha, Nebraska, was the first home of Malcolm Little with his birth family. The house was torn down in 1965 by new owners who did not know of its connection with Malcolm X. The site was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1984. A Nebraska Historical Marker now marks the site. The Malcolm X—Ella Little-Collins House in the Roxbury section of Boston, Massachusetts, where Malcolm X lived with his half-sister Ella Little-Collins and began getting involved in the Nation of Islam, was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 2021. Several archaeological surveys have been performed on the house's grounds, and there are ongoing efforts to preserve the site.

In Lansing, Michigan, a Michigan Historical Marker was erected in 1975 on Malcolm Little's childhood home. The city is also home to El-Hajj Malik El-Shabazz Academy, a public charter school with an Afrocentric focus. The school is located in the building where Little attended elementary school.

In cities across the United States, Malcolm X's birthday (May 19) is commemorated as Malcolm X Day. The first known celebration of Malcolm X Day took place in Washington, D.C., in 1971. The city of Berkeley, California, has recognized Malcolm X's birthday as a citywide holiday since 1979.

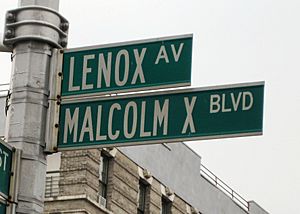

Many cities have renamed streets after Malcolm X. In 1987, New York mayor Ed Koch proclaimed Lenox Avenue in Harlem to be Malcolm X Boulevard. The name of Reid Avenue in Brooklyn, New York, was changed to Malcolm X Boulevard in 1985. Brooklyn also has El Shabazz Playground that was named after him. New Dudley Street, in the Roxbury neighborhood of Boston, was renamed Malcolm X Boulevard in the 1990s. In 1997, Oakland Avenue in Dallas, Texas, was renamed Malcolm X Boulevard. Main Street in Lansing, Michigan, was renamed Malcolm X Street in 2010. In 2016, Ankara, Turkey, renamed the street on which the U.S. is building its new embassy after Malcolm X.

Dozens of schools have been named after Malcolm X, including Malcolm X Shabazz High School in Newark, New Jersey, Malcolm Shabazz City High School in Madison, Wisconsin, Malcolm X College in Chicago, Illinois, and El-Hajj Malik El-Shabazz Academy in Lansing, Michigan. Malcolm X Liberation University, based on the Pan-Africanist ideas of Malcolm X, was founded in 1969 in North Carolina.

In 1996, the first library named after Malcolm X was opened, the Malcolm X Branch Library and Performing Arts Center of the San Diego Public Library system.

The U.S. Postal Service issued a Malcolm X postage stamp in 1999. In 2005, Columbia University announced the opening of the Malcolm X and Dr. Betty Shabazz Memorial and Educational Center. The memorial is located in the Audubon Ballroom, where Malcolm X was assassinated. Collections of Malcolm X's papers are held by the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture and the Robert W. Woodruff Library.

After a community-led initiative, Conrad Grebel University College in Canada (affiliated with the University of Waterloo) launched the Malcolm X Peace and Conflict Studies Scholarship in 2021 to support Black and Indigenous students enrolled in their Master of Peace and Conflict Studies program.

Portrayal in film, in television, and on stage

In 1986, composer Anthony Davis's opera X, The Life and Times of Malcolm X premiered at the New York City Opera. It was the first work by Davis, who would go on to win the Pulitzer Prize for Music for his opera The Central Park Five (2019). In 2023, it was performed at the Metropolitan Opera in a production by Robert O'Hara, with Will Liverman playing the title role. It received positive reviews.

Arnold Perl and Marvin Worth attempted to create a drama film based on The Autobiography of Malcolm X, but when people close to the subject declined to talk to them they decided to make a documentary instead. The result was the 1972 documentary film Malcolm X.

Denzel Washington played the title role in Spike Lee's film Malcolm X (1992). Roger Ebert and Martin Scorsese included it on their lists of the ten best films of the 1990s. Washington had previously played the part of Malcolm X in the 1981 Off-Broadway play When the Chickens Came Home to Roost.

Other portrayals include:

- James Earl Jones, in the 1977 film The Greatest.

- Dick Anthony Williams, in the 1978 television miniseries King and the 1989 American Playhouse production of the Jeff Stetson play The Meeting.

- Al Freeman Jr., in the 1979 television miniseries Roots: The Next Generations.

- Morgan Freeman, in the 1981 television movie Death of a Prophet.

- Ben Holt, in the 1986 opera X, The Life and Times of Malcolm X at the New York City Opera.

- Gary Dourdan, in the 2000 television movie King of the World.

- Joe Morton, in the 2000 television movie Ali: An American Hero.

- Mario Van Peebles, in the 2001 film Ali.

- Lindsay Owen Pierre, in the 2013 television movie Betty & Coretta.

- François Battiste, in the stage play One Night in Miami, first performed in 2013.

- Nigél Thatch, in the 2014 film Selma and the 2019 television series Godfather of Harlem.

- Kingsley Ben-Adir, in the 2020 film One Night in Miami, based on the play of the same name.

- Jason Alan Carnell, in the 2023 season of the television series Godfather of Harlem.

- Aaron Pierre, in the 2024 season of the television series Genius.

Published works

- The Autobiography of Malcolm X. With the assistance of Alex Haley. New York: Grove Press, 1965. .

- Malcolm X Speaks: Selected Speeches and Statements. George Breitman, ed. New York: Merit Publishers, 1965. .

- Malcolm X Talks to Young People. New York: Young Socialist Alliance, 1965. .

- Two Speeches by Malcolm X. New York: Pathfinder Press, 1965. .

- Malcolm X on Afro-American History. New York: Merit Publishers, 1967. .

- The Speeches of Malcolm X at Harvard. Archie Epps, ed. New York: Morrow, 1968. .

- By Any Means Necessary: Speeches, Interviews, and a Letter by Malcolm X. George Breitman, ed. New York: Pathfinder Press, 1970. .

- The End of White World Supremacy: Four Speeches by Malcolm X. Benjamin Karim, ed. New York: Monthly Review Press, 1971. .

- The Last Speeches. Bruce Perry, ed. New York: Pathfinder Press, 1989. ISBN: 978-0-87348-543-2.

- Malcolm X Talks to Young People: Speeches in the United States, Britain, and Africa. Steve Clark, ed. New York: Pathfinder Press, 1991. ISBN: 978-0-87348-962-1.

- February 1965: The Final Speeches. Steve Clark, ed. New York: Pathfinder Press, 1992. ISBN: 978-0-87348-749-8.

- The Diary of Malcolm X: 1964. Herb Boyd and Ilyasah Shabazz, eds. Chicago: Third World Press, 2013. ISBN: 978-0-88378-351-1.

Images for kids

-

Muhammad Ali (born Cassius Clay) (second row, in dark suit) watches Elijah Muhammad speak, 1964

-

Malcolm X's only meeting with Martin Luther King Jr., March 26, 1964, during the Senate debates regarding the (eventual) Civil Rights Act of 1964.

-

Louis Farrakhan in 2005

See also

In Spanish: Malcolm X para niños

In Spanish: Malcolm X para niños