Lessons for Children facts for kids

Lessons for Children is a series of four age-adapted reading primers written by the prominent 18th-century British poet and essayist Anna Laetitia Barbauld. Published in 1778 and 1779, the books initiated a revolution in children's literature in the Anglo-American world. For the first time, the needs of the child reader were seriously considered: the typographically simple texts progress in difficulty as the child learns. In perhaps the first demonstration of experiential pedagogy in Anglo-American children's literature, Barbauld's books use a conversational style, which depicts a mother and her son discussing the natural world. Based on the educational theories of John Locke, Barbauld's books emphasise learning through the senses.

One of the primary morals of Barbauld's lessons is that individuals are part of a community; in this she was part of a tradition of female writing that emphasised the interconnectedness of society. Charles, the hero of the texts, explores his relationship to nature, to animals, to people, and finally to God.

Lessons had a significant effect on the development of children's literature in Britain and the United States. Maria Edgeworth, Sarah Trimmer, Jane Taylor, and Ellenor Fenn, to name a few of the most illustrious, were inspired to become children's authors because of Lessons and their works dominated children's literature for several generations. Lessons itself was reprinted for over a century. However, because of the disrepute that educational writings fell into, largely due to the low esteem awarded Barbauld, Trimmer, and others by contemporary male Romantic writers, Barbauld's Lessons has rarely been studied by scholars. In fact, it has only been analysed in depth since the 1990s.

Contents

Publication, structure, and pedagogical theory

Publication and structure

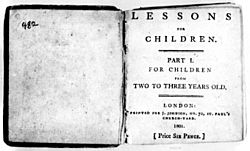

Lessons depicts a mother teaching her son. Presumably, many of the events were inspired by Barbauld's experiences of teaching her own adopted son, her nephew Charles, as the events correlate with his age and growth. Although there are no surviving first edition copies of the works, children's literature scholar Mitzi Myers has reconstructed the probable publication dates from Barbauld's letters and the books' earliest reviews as follows: Lessons for Children of two to three (1778); Lessons for Children of three, part I (1778); Lessons for Children of three, part II (1778); and Lessons for Children of three to four (1779). After its initial publication, the series was often published as a single volume.

Barbauld demanded that her books be printed in large type with wide margins, so that children could easily read them; she was more than likely the "originator" of this practice, according to Barbauld scholar William McCarthy, and "almost certainly [its] popularizer". In her history of children's literature in The Guardian of Education (1802–1806), Sarah Trimmer noted these innovations, as well as the use of good-quality paper and large spaces between words. While making reading easier, these production changes also made the books too expensive for the children of the poor, therefore Barbauld's books helped to create a distinct aesthetic for the middle-class children's book.

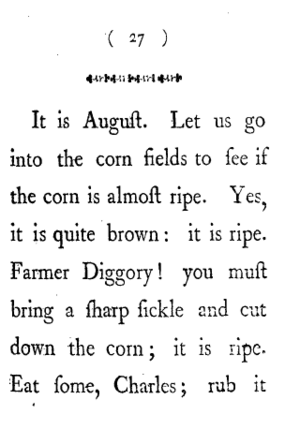

Barbauld's texts were designed for the developing reader, beginning with words of one syllable and progressing to multi-syllabic words. The first part of Lessons includes simple statements such as: "Ink is black, and papa's shoes are black. Paper is white, and Charles's frock is white." The second part increases in difficulty: "February is very cold too, but the days are longer, and there is a yellow crocus coming up, and the mezereon tree is in blossom, and there are some white snow-drops peeking up their little heads."

Barbauld also "departs from previous reading primers by introducing elements of story, or narrative, piecemeal before introducing her first story": the narrator explains the idea of "sequentiality" to Charles, and implicitly to the reader, before ever telling him a story. For example, the days of the week are explained before Charles's trip to France.

Pedagogical theory

Barbauld's Lessons emphasises the value of all kinds of language and literacy; not only do readers learn how to read but they also acquire the ability to understand metaphors and analogies. The fourth volume in particular fosters poetic thinking and as McCarthy points out, its passages on the moon mimic Barbauld's poem "A Summer Evening's Meditation":

| Lessons for Children | "A Summer Evening's Meditation" | |

|---|---|---|

| The Moon says My name is Moon; I shine to give you light in the night when the sun is set. I am very beautiful and white like silver. You may look at me always, for I am not so bright as to dazzle your eyes, and I never scorch you. I am mild and gentle. I let even the little glow-worms shine, which are quite dark by day. The stars shine all round me, but I am larger and brighter than the stars, and I look like a large pearl amongst a great many small sparkling diamonds. When you are asleep I shine through your curtains with my gentle beams, and I say Sleep on, poor little tired boy, I will not disturb you. |

A tongue in every star that talks with man, |

Barbauld also developed a particular style that would dominate British and American children's literature for a generation: an "informal dialogue between parent and child", a conversational style that emphasised linguistic communication. Lessons starts out monopolised by the mother's voice but slowly, over the course of the volumes, Charles's voice is increasingly heard as he gains confidence in his own ability to read and speak. This style was an implicit critique of late 18th-century pedagogy, which typically employed rote learning and memorisation.

Barbauld's Lessons also illustrates mother and child engaging in quotidian activities and taking nature walks. Through these activities, the mother teaches Charles about the world around him and he explores it. This, too, was a challenge to the pedagogical orthodoxy of the day, which did not encourage experiential learning. The mother shows Charles the seasons, the times of the day, and different minerals by bringing him to them rather than simply describing them and having him recite those descriptions. Charles learns the principles of "botany, zoology, numbers, change of state in chemistry ... the money system, the calendar, geography, meteorology, agriculture, political economy, geology, [and] astronomy". He also inquires about all of them, making the learning process dynamic.

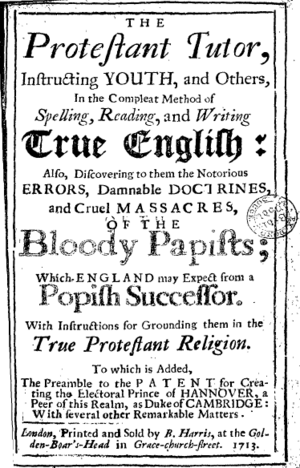

Barbauld's pedagogy was fundamentally based on John Locke's Some Thoughts Concerning Education (1693), the most influential pedagogical treatise in 18th-century Britain. Building on Locke's theory of the Association of Ideas, which he had outlined in Some Thoughts, philosopher David Hartley had developed an associationist psychology that greatly influenced writers such as Barbauld (who had read Joseph Priestley's redaction of it). For the first time, educational theorists and practitioners were thinking in terms of developmental psychology. As a result, Barbauld and the women writers she influenced produced the first graded texts and the first body of literature designed for an age-specific readership.

Themes

Lessons not only teaches literacy, "it also initiates the child [reader] into the elements of society's symbol-systems and conceptual structures, inculcates an ethics, and encourages him to develop a certain kind of sensibility". One of the series' overall aims is to demonstrate that Charles is superior to the animals he encounters—because he can speak and reason, he is better than they are. Lessons for Children, of Three Years Old, part 2 begins:

Do you know why you are better than Puss? Puss can play as well as you; and Puss can drink milk, and lie upon the carpet; and she can run as fast as you, and faster too, a great deal; and she can climb trees better; and she can catch mice, which you cannot do. But can Puss talk? No. Can Puss read? No. Then that is the reason why you are better than Puss—because you can talk and read.

Andrew O'Malley writes in his survey of 18th-century children's literature, "from helping poor animals [Charles] eventually makes a seamless transition to performing small acts of charity for the poor children he encounters". Charles learns to care for his fellow human beings through his exposure to animals. Barbauld's Lessons is not, therefore, Romantic in the traditional sense; it does not emphasise the solitary self or the individual. As McCarthy puts it, "every human being needs other human beings in order to live. Humans are communal entities".

Lessons was probably meant to be paired with Barbauld's Hymns in Prose for Children (1781), which were both written for Charles. As F. J. Harvey Darton, an early scholar of children's literature, explains, they "have the same ideal, in one aspect held by Rousseau, in another wholly rejected by him: the belief that a child should steadily contemplate Nature, and the conviction that by so doing he will be led to contemplate the traditional God". However, some modern scholars have pointed to the lack of overt religious references in Lessons, particularly in contrast to Hymns, to make the claim that it is secular.

One important theme in Lessons is restriction of the child, a theme which has been interpreted both positively and negatively by critics. In what Mary Jackson has called the "new child" of the 18th century, she describes "a fondly sentimentalized state of childishness rooted in material and emotional dependency on adults" and she argues that the "new good child seldom made important, real decisions without parental approval ... In short, the new good child was a paragon of dutiful submissiveness, refined virtue, and appropriate sensibility." Other scholars, such as Sarah Robbins, have maintained that Barbauld presents images of constraint only to offer images of liberation later in the series: education for Barbauld, in this interpretation, is a progression from restraint to liberation, physically represented by Charles' slow movement from his mother's lap in the opening scene of first book, to a stool next to her in the opening of the subsequent volume, to his detachment from her side in the final book.

Primary sources

- Barbauld, Anna Laetitia. Lessons for Children, from Two to Three Years Old. London: Printed for J. Johnson, 1787. Eighteenth Century Collections Online.

- Barbauld, Anna Laetitia. Lessons for Children, of Three Years Old. Part I. Dublin: Printed and sold by R. Jackson, 1779. Eighteenth Century Collections Online.

- Barbauld, Anna Laetitia. Second Part of Lessons for Children of Three Years Old. Dublin: Printed and sold by R. Jackson, 1779. Eighteenth Century Collections Online.

- Barbauld, Anna Laetitia. Lessons for Children from Three to Four Years Old. London: Printed for J. Johnson, 1788. Eighteenth Century Collections Online.

Secondary sources

- Darton, F. J. Harvey. Children's Books in England: Five Centuries of Social Life. 3rd ed. Revised by Brian Alderson. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1982. .

- Jackson, Mary V. Engines of Instruction, Mischief, and Magic: Children's Literature in England from Its Beginnings to 1839. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1989. .

- Myers, Mitzi. "Of Mice and Mothers: Mrs. Barbauld's 'New Walk' and Gendered Codes in Children's Literature". Feminine Principles and Women's Experience in American Composition and Rhetoric. Eds. Louise Wetherbee Phelps and Janet Emig. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 1995.

- O'Malley, Andrew. The Making of the Modern Child: Children's Literature and Childhood in the Late Eighteenth Century. New York: Routledge, 2003. .

- Pickering, Samuel F., Jr. John Locke and Children's Books in Eighteenth-Century England. Knoxville: The University of Tennessee Press, 1981. .

- Richardson, Alan. Literature, Education, and Romanticism: Reading as Social Practice, 1780–1832. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1994. .

- Rodgers, Betsy. Georgian Chronicle: Mrs. Barbauld and Her Family. London: Methuen, 1958.

Missing pages 1–10.

See also

In Spanish: Lessons for Children para niños

In Spanish: Lessons for Children para niños