Joost van den Vondel facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Joost van den Vondel

|

|

|---|---|

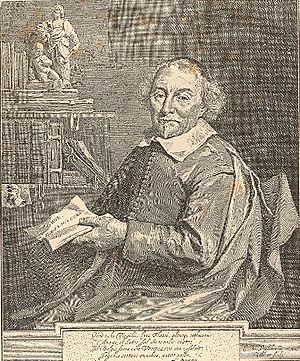

Vondel in 1665

|

|

| Born | 17 November 1587 Cologne, Holy Roman Empire |

| Died | 5 February 1679 (aged 91) Amsterdam, Dutch Republic |

| Occupation | Writer, playwright |

| Period | Dutch Golden Age |

| Spouse | Mayken de Wolff |

| Children | 4 |

| Signature | |

Joost van den Vondel (Dutch: [ˈjoːst fɑn dəɱ ˈvɔndəl]; 17 November 1587 – 5 February 1679) was the Dutch national poet, as well as an essayist, and playwright. He is widely considered the best poet of the 17th-century Dutch Golden Age and the pinnacle of Dutch literature.

Vondel remained productive until a very old age. Several of his most notable plays like Lucifer (play) and Adam in Exile were written after 1650, when he was already 65, and his final play Noah (play), written at the age of eighty, is considered one of his finest.

His plays are the ones from that period that are still most frequently performed, and his epic Joannes de Boetgezant (1662), on the life of John the Baptist, has been called the greatest Dutch epic.

Vondel's theatrical works were regularly performed until the 1960s. The most visible was the annual performance, on New Year's Day from 1637 to 1968, of Gijsbrecht van Aemstel.

Contents

Early life

Vondel was born on 17 November 1587 on the Große Witschgasse in the Free imperial city of Cologne, Holy Roman Empire. His parents, Joost van den Vondel the Elder and Sara (née Kranen), were Mennonite religious refugees from Antwerp, in the Spanish Netherlands. In 1595 the city officials informed all local Mennonites that they had to leave Cologne within fourteen days. The Vondel family was left adrift and lived at Frankfurt am Main, Bremen, Emden, and Utrecht, before eventually settling at Amsterdam in the newly formed Dutch Republic.

Mennonites were barely tolerated even in Amsterdam, as the State Church of the Dutch Republic was the Dutch Reformed Church, which belongs to the Continental Calvinist tradition within Protestantism. Despite this, Joost van den Vondel the Elder managed to acquire Dutch citizenship, which enabled him to set up a business, on 27 March 1597 and became a silk merchant on the Warmoesstraat.

From age ten, Vondel was schooled in the correct use of the Dutch literary language and also learnt French. It is thought that Vondel may have been a pupil of Willem Bartjens, to whom he would later dedicate an ode.

As the sons of merchants were not sent to the Latin schools, as an adult Vondel taught himself to read and write in the New Latin. He lived in an Amsterdam neighborhood filled with other Protestant refugees from Antwerp, and by 1606 was a member of the chamber of rhetoric of Het Wit Lavendel (The White Lavender), a literary society founded by Flemish immigrants from the Spanish Netherlands. Vondel is known to have signed his earliest verses, most of which were devotional Christian poetry filled with allusions to Classical mythology, with the motto Liefde verwinnet al ("Love conquers all"). Although the signing of poems with similar mottos was very common in Dutch culture at the time, Vondel is believed to have been referring, as a believing Mennonite, to the love of Jesus Christ for the human race.

In 1606 Vondel received Mennonite adult baptism. The following year his father died, and Vondel was brought into the family business as a partner.

The making of a poet

According to Watson Kirkconnell, Vondel began writing stage plays, "for the great public theatre at Amsterdam at a time when it's European reputation had succeeded to the expiring glories of the London stage."

In 1612, Vondel published his first play, Het Pascha ("Passover"), which dramatizes the events of the Book of Exodus and features an epilogue comparing the liberation of the enslaved Israelites from Biblical Egypt to Christ's redemption of the Human Race and to the success of the Dutch Revolt against King Philip II of Spain.

At the age of 23, Vondel married Mayken de Wolff. Together they had four children, of whom two died in infancy.

In the meantime, he began to learn New Latin and became acquainted with famous poets, such as Roemer Visscher.

During his early life, Vondel became one of the most vocal advocates for religious toleration. After the trial of Johan van Oldenbarnevelt for supporting the Arminians, his beheading at the command of Prince Maurits of Nassau, and the Synod of Dort (1618–1619), the Extreme Calvinist Gomarist faction seized absolute power over the Dutch Reformed Church and transformed the Dutch Republic into a Theocracy. Followers of Roman Catholicism, Anabaptism and Arminianism were subjected to religious persecution, but continued to worship in clandestine churches.

These events forced Vondel to seriously question his religious beliefs. As a Mennonite, Vondel was expected upon principle to take no part in the affairs of the State. In reaction to the events in the Republic, however, Vondel began suffering, according to Geeraardt Brandt, from, "a long languishing sickness, which greatly weakened him, exhausting his spirits and making him long for death."

It is now know that Vondel suffered from major depression for much of 1620 and that a second period also occurred in 1626. Simultaneously, however, Vondel wrote many plays and satires criticizing the Gomarists, which made him a very unpopular figure in both Church and State circles. In October 1620, Vondel resigned as Deacon of his Mennonite congregation and, "complained of great awkwardness in serving further because of his melancholia."

In 1620, Vondel, who by this time had taught himself Latin, completed the play Hierusalem verworst ("Jerusalem Destroyed"), which was heavily influenced by Seneca the Younger's Troades and by the French poetry and plays of Huguenots Robert Garnier and Guillaume de Salluste Du Bartas. Vondel signed his play with the motto, "Door Een is 't nu voldaen" ("By One all is now fulfilled").

Dissident

In 1622, Vondel baited the Gomarists by writing odes in honour of Erasmus of Rotterdam. He also granted shelter for several days to fugitive Arminian minister Coenraad Vorstius. When Vorstius died in October 1622, Vondel composed an elegy for him.

Vondel also increasingly immersed himself in the Roman poetry of Ovid, Virgil, and Horace, as well as in the cultural and literary scholarship of the era, as well as moral philosophy and logic. According to Geeraardt Brandt, Vondel sought to, "have more means of assistance in progressing at art, which he threw himself into more and more as time went on."

His 1625 play Palamedes sought to evade censorship by concealing his fictionalization of the trial of Oldenbarnevelt behind Odysseus' frame-up of Palamedes during the Trojan War. While Vondel's play did not fool anybody and caused him to be heavily fined, his play proved widely popular and went through seven editions. As a further effort to improve his Latin, Vondel then proceeded to translate Seneca's plays Troades and Phaedra into Dutch as De Amsteldamsche Hecuba (1626) and Hyppolytus (1628).

Vondel was widowed when Mayken de Wolff died in 1635.

In 1637, Vondel completed his play Gysbrecht van Amstel, which was intended to be staged on Christmas Day to celebrate the recent completion of the Amsterdam Schouwburg by Jacob van Campen. The play, which retells the 13th century siege and destruction of Amsterdam, was banned by the Dutch Government after they learned that a Catholic Mass was to be shown on stage. A very heavily censored version of the play had its delayed premiere in 1638.

As part of his growing fascination with the theatre of ancient Greece, Vondel's translation of Sophocles' Electra was completed in 1639.

Around the year 1641, Vondel converted to the Roman Catholic Church. Although the intellectual process behind his conversion remains largely unknown, Vondel's well-documented opposition to Calvinist-inspired censorship, the religious persecution of non-Calvinists, and his love for a Roman Catholic woman are all very likely to have played a role.

According to P.H. Albers, the Dutch Reformed ministers (Dominies) of the Gomarist faction had accused Vondel's writings of expressing Catholic sympathies for several years previous to his conversion. Furthermore, the 1641 Litterae Annuae states that Vondel was received into the Catholic Church in the Netherlands by underground priests of the Society of Jesus inside a clandestine church located near the modern site of De Krijtberg at Singel 448. Father Petrus Laurentius, S.J. is believed to at least have participated in Vondel's conversion.

Even though it was a great shock to many of the Dutch people, Vondel's conversion to Catholicism was very sincere and he vigorously defended the doctrines of his new Faith in his subsequent literary works. In 1645, Vondel defended the doctrines of the Real Presence within the Blessed Sacrament in the Altaargeheimenissen ("Mysteries of the Altar").

Vondel also defended his new Faith in De heerlijkheid der kerke ("On the Church").

In 1646, Vondel paid tribute to Mary, Queen of Scots in Maria Stuart of Gemartelde Majesteit ("Mary Stuart, or the Martyred Majesty"). Vondel depicted the Scottish Queen as a Catholic martyr and as the innocent victim of the Protestant tyrant, Queen Elizabeth I. As Dutch censors also correctly viewed Vondel's play as a veiled commentary upon the ongoing English Civil War between King Charles I and Oliver Cromwell, Maria Stuart was also banned and its author was fined 180 guilders.

During this era Vondel is known, at the very least, to have been an acquaintance of Rembrandt van Rijn, the most acclaimed master of Dutch Golden Age painting. For example, several epigrams survive by Vondel about Rembrandt's paintings. Furthermore, a number of sketches also survive in which Rembrandt depicts characters from Vondel's Gysbrecht van Amstel. Wytze Hellinga's hypothesis, however, that Rembrandt's iconic painting The Night Watch is depicting the opening scene of the same play, is not universally accepted. The nature of Vondel and Rembrandt's relationship and opinion of one another, however, continues to be debated.

In 1654, Vondel published the stage play that is still considered his masterpiece, Lucifer. The play drew heavily upon Vondel's careful study of Aristotle's admonition that the protagonist of a tragedy should not be blameless, should be somewhere between good and evil, and should ultimately be brought down by his or her own shortcomings. During Act V, the Archangel Gabriel announces the Fall and Banishment of Adam and Eve.

By this time, Vondel had become a passionate believer in Monarchism and accordingly dedicated his play to the Holy Roman Emperor Ferdinand III. Vondel used Lucifer to defend the thesis that the authority of a just Monarch, like that of the Christian God, is divinely ordained and inviolable. Therefore, Vondel used his depiction of the Revolt in Heaven to criticize Calvinism, the ongoing English Civil War, and even to question the validity of the Dutch Revolt led by William the Silent against King Phillip II, by, according to Watson Kirkconnell, and among many other things, depicting Lucifer's heavenly chariot as bearing the same symbolism as the coat of arms of the House of Orange-Nassau.

In addition to these reasons, the play's settling in Heaven and its depiction of the Fall of the Angels and of Mankind, made it unacceptable to the Dutch Reformed Church. Lucifer was accordingly banned after only two performances and its stock was confiscated. Lucifer was also condemned from the pulpits and interdicted by the Dominies. Ironically, this ban made Vondel's play so popular that it ran through four editions in just the first year of its publication (1654).

But as the theatre had invested a great deal of money in costumes and sets that could be used to depict Heaven, the banning of Lucifer caused a devastating financial loss. Vondel tried to further evade censorship and help the theater to recoup its losses by adapting the same subject to Greek mythology by composing a play about Salmoneus, the King of Elis, who aspired to be worshipped just like the god Zeus. Even so, the Government of the Dutch Republic prevented Salmoneus from being staged until 1657.

According to Riet Schenkeveld-van der Dussen, the banning of Vondel's plays was not only because the Gomarist leadership of the Dutch Reformed Church opposed the theater on general principle or even because of the playwright's Catholicism. By putting the events described in the Christian Bible upon the public stage, Vondel was threatening the Dominies' monopoly upon religion and its interpretation. No debates on the banning of Vondel's plays were ever allowed, as debates would have revealed that Vondel's religious vision was actually one which most 17th-century Dutch people would not have found objectionable in any way.

Vondel's 1659 play Jeptha, whose subject is drawn from the 11th Chapter of the Book of Judges, further improved upon his ability to adapt the structure of Greek Tragedy (hamartia, peripeteia, and anagnorisis) to a story drawn from the Old Testament. However, Vondel's depiction of Jephthah as a tragic hero failed to interest Dutch theatergoers, who increasingly preferred French-style Baroque dramas.

Between 1659 and 1667, Vondel published ten tragedies. They included his literary translations into the Dutch language of Sophocles' Oedipus Rex ("Koning Edipus", 1660) and Euripides' Iphigenia in Tauris ("Ifigenie in Tauren", 1666). He also continued writing Neo-Classical plays about figures from the Old Testament who experience peripeteia, or a drastic reversal of fortune. His 1660 plays Koning David in Ballingschap ("King David in Exile") and Koning David herstellt ("King David Restored") both centered upon the conflict between King David and his son Absalom. His 1660 play Samson dealt with the title character's enslavement by the Philistines and ultimate revenge. Vondel's 1661 play Adonias dealt with the efforts of Adonijah to depose his younger brother Solomon.

Later life

In 1663, Vondel interrupted his Biblical plays by writing Batavische gebroeders ("The Batavian Brothers"), which dramatizes Tacitus' account of the revolt of the Batavi led by Claudius Civilis against the Roman Empire in 69 AD. Vondel depicted Civilis and his brother as heroic ancestors of the Dutch people and as victims of foreign tyranny and colonialism.

In his 1667 play Noah, of Ondergang der eerste weerelt ("Noah, or the Downfall of the First World"), completed what Vondel intended as a trilogy, along with Lucifer and Adam in Ballingschap ("Adam in Exile"), "about the fall and punishment of Man and the prospect of salvation."

After being impoverished by his efforts to pay his late son's debts, Joost van den Vondel died a bitter man, at 91 years of age, on 5 February 1679. In honour of his status as the greatest poet of the Dutch Golden Age, Vondel was carried to his grave in Amsterdam's Nieuwe Kerk, "by fourteen poets and lovers of poetry."

Alleged influence upon John Milton

During the 1880s, it was suggested by George Edmundson that John Milton drew inspiration from Vondel's stage plays Lucifer (1654) and Adam in Ballingschap (1664) for the writing of the epic poem Paradise Lost (1667). According to Watson Kirkconnell, Edmundson demonstrated, "scores of parallels."

Despite the religious differences between their authors, their works have similarities: the focus on Lucifer, the description of the battle in heaven between Lucifer's forces and St. Michael's, and the anti-climax as Adam and Eve leave Paradise.

One example of similarity is the following:

"Is ’t noodlot, dat ick vall’, van eere en staet berooft,

Laet vallen, als ick vall’, met deze kroone op ’t hooft,

Dien scepter in de vuist, dien eersleip van vertrouden,

En zoo veel duizenden als onze zyde houden.

Dat valle streckt tot eer, en onverwelckbren lof:

En liever d’ eerste Vorst in eenigh laeger hof,

Dan in ’t gezalight licht de tweede, of noch een minder

Zoo troost ick my de kans, en vrees nu leet noch hinder."

Translation:

Is it fate that I will fall, robbed of honour and dignity,

Then let me fall, if I were to fall, with this crown upon my head

This sceptre in my fist, this company of loyals,

And as many as are loyal to our side.

This fall would honour one, and give unwilting praise:

And rather [would I be] foremost king in any lower court,

Than rank second in most holy light, or even less

Thus I justify my revolt, and will not fear pain nor hindrance.

- Vondel's Lucifer

- "Here may we reign secure, and in my choice

- To reign is worth ambition, though in Hell.

- Better to reign in hell than serve in heaven."

- Milton's Paradise Lost

These and other similarities ultimately inspired one highly important figure in Milton scholarship, who also admired Vondel very deeply, to include the Dutch playwright in one of the great literary translation projects in modern Canadian literature.

By 1916, lack of interest in the poetry of John Milton and distaste for his Puritanism had reached a new low. Due in large part to the efforts of Ezra Pound and T.S. Eliot, the Puritan poet was even declared deposed, with little or no fanfare, in favor of John Donne and Andrew Marvell, as the Anglosphere's greatest composer of Christian poetry. In response, Canadian poet and literary scholar Watson Kirkconnell sought to return John Milton to his pedestal by translating and publishing what had long been believed to been the poet's many sources of inspiration from World literature in many other languages.

Paradise Lost

Kirkconnell began, during the 1930s, translate both Vondel plays, Lucifer (1654) and Adam in Ballingschap (1664), into English Blank Verse. Kirkconnell was later to publish both plays through the University of Toronto in the 1952 collection The Celestial Cycle: The Theme of Paradise Lost: in World Literature with Translations of the Major Analogues.

Although unaware until much later of Vondel's well-documented hostility to the religious persecution and censorship imposed upon the Dutch Republic by the Dutch Reformed Church ministers following the Synod of Dort, Kirkconnell did notice that both of Vondel's plays about Lucifer offered very harsh criticisms of Calvinism and defended theological beliefs completely opposed to the Puritanism of John Milton. According to Kirkconnell, "Vondel's portrayal of Lucifer, which seems to combine traits of William I of Orange and of Cromwell, in settings reminiscent of the Dutch and English revolutions, is immensely interesting. In the case of Adam in Ballingschap, Vondel's own introduction acknowledges his debt to the Latin play of Grotius, but his treatment is much more free, and the metre is that of contemporary French drama."

Writing in 1952, Kirkconnell laid out his case that Milton was aware of Vondel. To prove that Milton knew the Dutch language, Kirkconnell quoted a 12 July 1654 letter by Roger Williams to John Winthrop, "The Secretary of the Council, Mr. Milton, for my Dutch I read him, read me many more languages."

Kirkconnell elaborated, "In the period 1649-54, moreover, Milton was closely in touch with events in Holland... The storm of Calvinist church criticism that forced the withdrawal of Vondel's Lucifer from the Dutch stage after two days in January 1654 - and caused the first edition to sell out almost immediately - could not have failed to arouse Milton's keen interest."

Samson Agonistes

Kirkconnell also believed strongly enough that Vondel's Samson of Heilige Wraeck, Treurspel was similarly a major influence upon John Milton's Samson Agonistes, that he made and published another Vondel translation into English Blank Verse in the 1964 volume That Invincible Samson: The Theme of Samson Agonistes in World Literature with Translations of the Major Analogues. In the introduction, Kirkconnell called Milton's Samson Agonistes, "the noblest treatment of it's theme ever written, approached in literary quality only by Vondel."

Legacy

According to Watson Kirkconnell, "Vondel is to the Netherlands what Shakespeare is to England, although in dramatic and poetic rank he is closer to Dryden than to Shakespeare."

Sir Edmund Gosse has written, "This venerable and illustrious person, the main literary glory of Holland through her whole history... is the typical example of Dutch intelligence and imagination at their highest development. Not merely is he to Holland all that Camoens is to Portugal and Mickiewicz is to Poland, but he stands on a level with these men in the positive value of his writings."

P.H. Albers has also written of Vondel, "He is the greatest poet the Netherlands have produced, one who is distinguished in every form and who occupies a place among the best poets of all time."

Even so, Vondel long remained a controversial figure, and not just among orthodox Calvinists. Vondel's first biographer, the Arminian minister Geeraardt Brandt, "makes it fairly plain that he held the explicitly Roman Catholic Vondel in less than high regard."

At the same time, however, the poet Andries Pels considered Vondel one of the, "greatest and brightest lights of the Dutch language", and praised the theory of drama expounded in Vondel's preface to Jeptha. By 1730, even as new editions of Gysbreght van Aemstel appeared only after all pro-Catholic passages had first been removed, the playwright and literary critic Balthasar Huydecoper declared, "all poets nowadays have their eyes on Vondel", whose language had become the prevailing, "language of Parnassus." At the same time, however, Vondel's Catholicism remained, "something to be glossed over whenever possible".

By the time the Batavian Republic finally granted the members of the formerly persecuted Catholic Church in the Netherlands full emancipation during the Napoleonic Wars, Vondel had become a hero to his fellow Dutch Catholics, who became the first to depict the playwright, "as a champion of the Counter-Reformation and a great Baroque poet, presenting him as the literary counterpart to Rubens."

During the 19th century, Romantic nationalism led to Vondel-themed literary festivals in Amsterdam and many other Dutch cities. Another feature of the era were acrimonious debates over the allegedly subversive Catholicism in his plays.

All works of Joost van den Vondel (WB-editie) were published in 10 volumes (1927-1937).

Since the 1960s, however, the mass Secularisation of Dutch culture outside of the Dutch Bible belt has resulted in a falling off of interest. As even, "in his political and historical dramas... with few exceptions, Christian thought is central", Vondel is no longer taught or read in Dutch secondary schools. As a result, many Dutch people are now unable to understand the literary language of the Dutch Golden Age and accordingly feel unable to identify with Vondel's plots, characters, and ideas. Similarly to the plays of William Shakespeare, the lengthy speeches and soliloquies of Vondel's characters now represent a challenge for actors to perform without boring and irritating modern audiences.

Even so, the Dutch five guilder banknote bore Vondel's portrait from 1950 until they were discontinued in 1990.

Amsterdam's biggest park, the Vondelpark, also still bears his name. There is a statue of Vondel in the northern part of the park. Also, there is also a Vondelstraße in the Neustadt-Süd-district of his native Cologne.

Moreover, the Dutch people are still very proud of Vondel, about whom they often say, "He is the Prince of our Poets".

Plays

His plays included:

- The Passover or the Redemption of Israel from Egypt (1610),

- Jerusalem Destroyed (1620),

- Palamedes (1625),

- Hecuba (1626),

- Joseph (1635),

- Gijsbrecht van Aemstel (1637),

- The Maidens (1639),

- The Brothers (1640),

- Joseph in Dothan (1640),

- Joseph in Egypt (1640),

- Peter and Paul (1641),

- Mary Stuart or Tortured Majesty (1646),

- Lion Fallers (1647),

- Solomon (1648),

- Lucifer (1654),

- Salmoneus (1657),

- Jephthah (1659),

- David in Exile (1660),

- David Restored (1660),

- Samson or Holy Revenge (1660),

- The Sigh of Adonis (1661),

- The Batavian Brothers or Oppressed Freedom (1663),

- Phaeton (1663),

- Adam in Exile from Eden (1664),

- The Destruction of the Sinai Army (1667),

- Noah and the Fall of the First World (1667).

Commemoration

Amsterdam's biggest park, the Vondelpark, bears his name. There is a statue of Vondel in the northern part of the park. Also, there is a Vondel Street in Cologne, the Vondelstraße in the Neustadt-Süd-district.

The Dutch five guilder banknote bore Vondel's portrait from 1950 until it was discontinued in 1990.

All works of Joost van den Vondel (WB-editie) were published in 10 volumes (1927-1937).

See also

In Spanish: Joost van den Vondel para niños

In Spanish: Joost van den Vondel para niños