John R. Anderson (minister) facts for kids

Quick facts for kids John R. Anderson |

|

|

|

| Born | 1818 in Shawneetown, Illinois |

|---|---|

| Died | May 20, 1863 (aged 44–45) in St. Louis, Missouri |

| Church | Central Baptist Church |

| Other names | J. Richard Anderson |

| Spouse | Nancy Barton Anderson |

John R. Anderson, also known as J. Richard Anderson (1818–May 20, 1863), was an American minister from St. Louis, Missouri, who fought against slavery and for education for African Americans. As a boy, he was an indentured servant, who attained his freedom at the age of 12. Anderson worked as a typesetter for the Missouri Republican and for Elijah Parish Lovejoy's anti-slavery newspaper, the Alton Observer. He founded the Antioch Baptist Church in Brooklyn, Illinois and then returned to St. Louis where he was a co-founder and the second pastor of the Central Baptist Church. He served the church until his death in 1863.

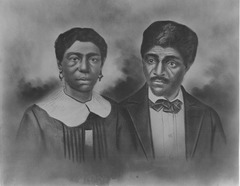

More than half of his congregants were slaves. Reverend Anderson helped enslaved people attain freedom by encouraging them to file freedom suits and by raising funds to emancipate them. He was a minister and spiritual advisor to Harriet Scott and Dred Scott, of the landmark Dred Scott v. Sandford Supreme Court case.

In 1854, Anderson operated the floating Freedom School, after its founder John Berry Meachum's death, and he lobbied for schools for black children. He worked with a ten-person board to bring subscription and public schools to the city. After ten years, a law was enacted in 1864 that provided funding for four or five public schools. There were four subscription schools also established by that year. He founded the first African American Masonic temple west of the Mississippi River in the early 1860s.

Early life and education

John Richard Anderson was born in 1818 in Shawneetown, Illinois. His parents had been enslaved in Virginia. As a child, Anderson moved with the family he belonged to, to Missouri. Legally, his past residence in Illinois territory meant that he was free. He moved to Missouri with Sarah Bates, the sister of United States Attorney General Edward Bates. While he was technically an indentured servant, he was treated like a slave until the age of 12, when he attained his freedom. Anderson and his mother Chloe Anderson were emancipated by Sarah Bates on January 25, 1830.

As a child, he learned to read at the Sunday school of the First Colored Church, which was established by Reverends James Welch and John Mason Peck. Anderson received most of his education in reading and theology at John Berry Meachum's "Freedom School," which was conducted on a riverboat in the Mississippi River. He sought to take advantage of evening schools in St. Louis, but was told to leave when it was discovered that he was not white. Anderson was baptized at the First African Baptist Church.

Newspapers

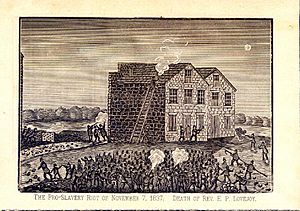

Anderson was hired out as a slave to distribute the Missouri Republican newspaper. He performed so well that he was taken into the office to work as a press roller, and then a typesetter. Anderson moved to Alton, Illinois with the anti-slavery activist and editor Elijah Parish Lovejoy and worked as his typesetter for the Alton Observer. He was working when Lovejoy was killed in Alton, Illinois in 1837, and was an eyewitness to his murder and the destruction of the printing press.

Ministry

Anderson was ordained at the Union Baptist Church in Alton. In 1838, Anderson founded the Antioch Baptist Church at his home in Brooklyn, Illinois. Back in St. Louis, he established a white-washing business with Richard Sneethen.

Anderson was a minister for the First African Baptist Church in St. Louis until he resigned in June 1846. With 20 others, he founded the Central Baptist Church in August 1846. Rev. Richard Sneethen was the church's first minister. In 1847, Anderson became an associate pastor of the church with Sneethen. When Sneethen accepted a new position at a church in Louisville, Kentucky, Anderson became the second pastor, a position he held from 1849 to 1863. More than half of the congregants were enslaved men and women. To walk the streets and attend church, they needed approval in the form of a pass from their slaveholders. Unable to support himself and his family on the earnings from the church, Anderson worked in the City Jail as an assistant police officer for the rest of his life.

In 1852, the edifice for the Central Baptist Church was completed at the cost of $12,000 (equivalent to $376,886 in 2022). Anderson gave one year's salary to the edifice fund and raised the rest of the money. Each year, he held a revival. By the 1850s, Anderson served more than 1,000 parishioners.

Activist

Anderson was an anti-slavery activist who provided loans to purchase the freedom of enslaved people, preventing them from being sold into the Deep South to work on cotton plantations. The Central Baptist Church acquired two of its deacons after Anderson bought them from the slave pen in St. Louis. They were Merriman Ramsey and Henry Lee. He helped African Americans file freedom suits in the courts. Anderson regularly carried baskets of food and other necessities for the poor and hungry.

Harriet Robinson Scott, a member of the Central Baptist Church, sought his advise for their freedom suit. Anderson was also a spiritual advisor to Harriet and her husband, Dred Scott.

After Meecham died in 1854, Anderson ran the Freedom School for African American children. With Galusha Anderson, a white Baptist minister, he lobbied the St. Louis school system for education for black children over a ten-year period. Anderson served on a board of education established to provide schooling for black students. It was the first and only board of its kind in the city. The ten members included three black ministers, two black businessmen, and three whites. A subscription school opened in 1856 that charged one dollar per pupil. By 1864, four public schools were established and there were also four subscription schools that operated out of the basements of black churches. This was accomplished during a period when the prevailing belief among pro-slavery and some anti-slavery factions that African Americans should not be educated. The St. Louis Board of Education petitioned the Legislature to enact laws to provide schools for African American children. A law was enacted in 1866 to provide funding for four or five public schools for $500 (equivalent to $9,355 in 2022).

Personal life

Anderson met Nancy Barton in Alton, and was married to her on November 9, 1838, in Madison, Illinois. They had five children: Mandy J., Simon P., May E., Matilda, and Martha Anderson. His son, Simon Peter Anderson was also a pastor of the Central Baptist Church, serving from 1868 to 1880 and 1885–1889.

He and Henry Mcghee Alexander had become masons during a trip to Boston and was then a member of the Colored Masons of St. Louis. In the early 1860s, he co-founded the McGhee Lodge (H. McGee Lodge) in St. Louis. It was the first masonic organization established for African Americans west of the Mississippi River.

He died of poisoning after a druggist accidentally made medicine for him from the root of a plant, rather than the leaf. He died on May 20, 1863, and was buried in the Bellefontaine Cemetery next to John Berry Meachum. A historical marker at the cemetery memorializes his efforts to provide education for African Americans and in recognition for his efforts as a minister and a community leader.