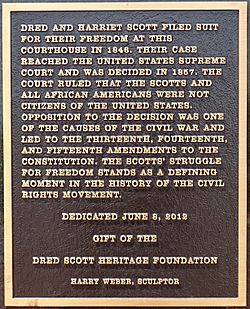

Dred Scott facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Dred Scott

|

|

|---|---|

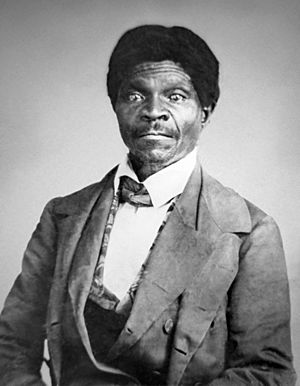

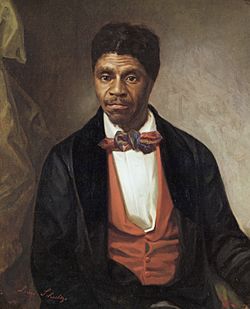

Scott c. 1857

|

|

| Born | c. 1799 |

| Died | September 17, 1858 (aged approximately 59) St. Louis, Missouri, U.S.

|

| Resting place | Calvary Cemetery |

| Known for | Dred Scott v. Sandford |

| Spouse(s) | |

| Children | 4 (2 died during infancy) |

Dred Scott (1799 – September 17, 1858) was a slave in the United States of America who took legal action to get his freedom in the Dred Scott v. Sanford case. His case was rejected by the Supreme Court.

Many people were angry at the decision, and slavery became one of the main issues in the American Civil War a few years later. Slavery was ended after the Confederate States of America surrendered.

Contents

Life

Dred Scott was born into slavery c. 1799 in Southampton County, Virginia. It is not clear whether Dred was his given name or a shortened form of Etheldred. In 1818, Dred was taken by Peter Blow and his family, with their five other slaves, to Alabama, where the family ran an unsuccessful farm in a location near Huntsville. This site is now occupied by Oakwood University.

The Blows gave up farming in 1830 and moved to St. Louis, Missouri, where they ran a boarding house. Dred Scott was sold to Dr. John Emerson, a surgeon serving in the United States Army, who planned to move to Rock Island, Illinois. After Scott learned this, he attempted to run away. His decision to do so was spurred by a distaste he had developed for Emerson. Scott was temporarily successful in his escape as he, much like many other runaway slaves during this time period, "never tried to distance his pursuers, but dodged around among his fellow slaves as long as possible". Eventually, he was captured in the "Lucas Swamps" of Missouri and taken back. (Blow died in 1832, and historians debate whether Scott was sold to Emerson before or after Blow's death. Some believe that Scott was sold in 1831, while others point to a number of enslaved people in Blow's estate who were sold to Emerson after Blow's death, including one with a name given as Sam, who may be the same person as Scott.)

As an army officer, Emerson moved frequently, taking Scott with him to each new army posting. In 1836, Emerson and Scott went to Fort Armstrong, in the free state of Illinois. In 1837, Emerson took Scott to Fort Snelling, in what is now the state of Minnesota and was then in the free territory of Wisconsin. There, Scott met and married Harriet Robinson, a slave owned by Lawrence Taliaferro. The marriage was formalized in a civil ceremony presided over by Taliaferro, who was a justice of the peace. Since slave marriages had no legal sanction, supporters of Scott later noted that this ceremony was evidence that Scott was being treated as a free man. But Taliaferro transferred ownership of Harriet to Emerson, who treated the Scotts as his slaves.

Dr. Emerson was transferred to Fort Jesup in Louisiana in 1837, leaving the Scott family behind at Fort Snelling and leasing them out (also called hiring out) to other officers. In February 1838, Emerson met and married Eliza Irene Sanford in Louisiana, whereupon he sent for the Scotts to join him, only to be reassigned to Fort Snelling later that year. While on a steamboat heading north on the Mississippi River, north of Missouri, Harriet Scott gave birth to their first child, whom they named Eliza. They later had a daughter, Lizzie. They also had two sons, but neither survived past infancy.

The Emersons and Scotts returned to Missouri, a slave state, in 1840. In 1842, Emerson left the Army. After he died in the Iowa Territory in 1843, his widow Irene inherited his estate, including the Scotts. For three years after Emerson's death, she continued to lease out the Scotts as hired slaves. In 1846, Scott attempted to purchase his and his family's freedom, offering $300, about $9,000 in current value. Irene Emerson refused his offer. Scott and his wife separately filed freedom suits to try to gain their freedom and that of their daughters. The cases were later combined by the courts.

Dred Scott v. Sandford

Summary

The Scotts' cases were first heard by the Missouri circuit court. The first court upheld the precedent of "once free, always free". That is, because the Scotts had been held voluntarily for an extended period by their owner in a free territory, which provided for slaves to be freed under such conditions. Therefore, the court ruled they had gained their freedom. The owner appealed. In 1852 the Missouri supreme court overruled this decision, on the basis that the state did not have to abide by free states' laws, especially given the anti-slavery fervor of the time. It said that Scott should have filed for freedom in the Wisconsin Territory.

Scott ended up filing a freedom suit in federal court (see below for details), in a case that he appealed to the US Supreme Court. The U.S. Supreme Court ruled that African descendants were not U.S. citizens and had no standing to sue for freedom. It also ruled that the Missouri Compromise was unconstitutional. This was the last in a series of freedom suits from 1846 to 1857, that began in Missouri courts, and were heard by lower federal district courts. The US Supreme Court overturned the earlier precedents, and established new limitations on African Americans.

Abolitionist aid to Scott's case

Scott's freedom suit before the state courts was backed financially by Peter Blow's adult children, who had turned against slavery in the decade since they sold Dred Scott. Henry Taylor Blow was elected as a Republican Congressman after the Civil War, Charlotte Taylor Blow married the son of an abolitionist newspaper editor, and Martha Ella Blow married Charles D. Drake, one of Scott's lawyers who was elected by the state legislature as a Republican US Senator. Members of the Blow family signed as security for Scott's legal fees and secured the services of local lawyers. While the case was pending, the St. Louis County sheriff held these payments in escrow and leased Scott out for fees.

In 1851, Scott was leased by Charles Edmund LaBeaume, whose sister had married into the Blow family. Scott worked as a janitor at LaBeaume's law office, which was shared with Roswell Field.

After the Missouri Supreme Court decision ruled against the Scotts, the Blow family concluded that the case was hopeless and decided that they could no longer pay Scott's legal fees. Roswell Field agreed to represent Scott pro bono before the federal courts. Scott was represented before the U.S. Supreme Court by Montgomery Blair. (The abolitionist later served in President Abraham Lincoln's cabinet as Postmaster General.) Assisting Blair was attorney George Curtis. His brother Benjamin was an Associate Supreme Court Justice and wrote one of the two dissents in Dred Scott v. Sandford.

In 1850, Irene Emerson remarried and moved to Springfield, Massachusetts. Her new husband, Calvin C. Chaffee, was an abolitionist. He was elected to the U.S. Congress in 1854 and fiercely attacked by pro-slavery newspapers for his apparent hypocrisy in owning slaves. In response, Chaffee said that neither he nor Mrs. Chaffee knew about the case until it was "noticed for trial". He wrote to Montgomery Blair, saying "my wife ... desires to know whether she has the legal power and right to emancipate the Dred Scott family."

Given the complicated facts of the Dred Scott case, some observers on both sides raised suspicions of collusion to create a test case. Abolitionist newspapers charged that slaveholders colluded to name a New Yorker as defendant, while pro-slavery newspapers charged collusion on the abolitionist side.

About a century later, a historian established that John Sanford never legally owned Dred Scott, nor did he serve as executor of Dr. Emerson's will. It was unnecessary to find a New Yorker to secure diversity jurisdiction of the federal courts, as Irene Emerson Chaffee (still legally the owner) had become a resident of Massachusetts. After the U.S. Supreme Court ruling, Roswell Field advised Dr. Chaffee that Mrs. Chaffee had full powers over Scott. However, Sanford had been involved in the case since the beginning, as he had secured a lawyer to defend Mrs. Emerson in the original state lawsuit before she married Chaffee.

Post-case freedom

Following the ruling, the Chaffees deeded the Scott family to Republican Congressman Taylor Blow, who manumitted them on May 26, 1857. Scott worked as a porter in a St. Louis hotel, but his freedom was short-lived; he died from tuberculosis in September 1858. He was survived by his wife and his two daughters.

Scott was originally interred in Wesleyan Cemetery in St. Louis. When this cemetery was closed nine years later, Taylor Blow transferred Scott's coffin to an unmarked plot in the nearby Catholic Calvary Cemetery, St. Louis, which permitted burial of non-Catholic slaves by Catholic owners. A local tradition later developed of placing Lincoln pennies on top of Scott's gravestone for good luck.

Harriet Scott was buried in Greenwood Cemetery in Hillsdale, Missouri. She outlived her husband by 18 years, dying on June 17, 1876. Their daughter, Eliza, married and had two sons. Her sister Lizzie never married but, following her sister's early death, helped raise her nephews. One of Eliza's sons died young, but the other married and has descendants, some of whom still live in St. Louis as of 2017.

See also

In Spanish: Dred Scott para niños

In Spanish: Dred Scott para niños