Jean Baudrillard facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Jean Baudrillard

|

|

|---|---|

Baudrillard in 2004 at the European Graduate School

|

|

| Born | 27 July 1929 Reims, France

|

| Died | 6 March 2007 (aged 77) Paris, France

|

| Alma mater | University of Paris |

| Era | 20th-/21st-century philosophy |

| Region | Western philosophy |

| School |

|

| Institutions |

|

| Thesis | Le système des objets (1968) |

| Doctoral advisor | Henri Lefebvre |

|

Main interests

|

|

|

Notable ideas

|

|

|

Influences

|

|

|

Influenced

|

|

Jean Baudrillard (UK: /ˈboʊdrɪjɑːr/ bohd-RIH-yar, US: /ˌboʊdriˈɑːr/ bohd-REE-ar, French: [ʒɑ̃ bodʁijaʁ]; 27 July 1929 – 6 March 2007) was a French sociologist, philosopher and poet with interest in cultural studies. He is best known for his analyses of media, contemporary culture, and technological communication, as well as his formulation of concepts such as hyperreality. Baudrillard wrote about diverse subjects, including consumerism, critique of economy, social history, aesthetics, Western foreign policy, and popular culture.

Contents

Biography

Baudrillard was born in Reims, northeastern France, on 27 July 1929. His grandparents were farm workers and his father a gendarme. During high school (at the Lycée at Reims), he became aware of pataphysics via philosophy professor Emmanuel Peillet, which is said to be crucial for understanding Baudrillard's later thought. He became the first of his family to attend university when he moved to Paris to attend the Sorbonne. There he studied German language and literature, which led him to begin teaching the subject at several different lycées, both Parisian and provincial, from 1960 until 1966.

During career as teacher

While teaching, Baudrillard began to publish reviews of literature and translated the works of such authors as Peter Weiss, Bertolt Brecht, Karl Marx, Friedrich Engels, and Wilhelm Emil Mühlmann.

While teaching German, Baudrillard began to transfer to sociology, eventually completing and publishing in 1968 his doctoral thesis Le Système des Objets (The System of Objects) under the dissertation committee of Henri Lefebvre, Roland Barthes, and Pierre Bourdieu. Subsequently, he began teaching Sociology at the Paris X Nanterre, a university campus just outside Paris which would become heavily involved in the events of May 1968. During this time, Baudrillard worked closely with Philosopher Humphrey De Battenburge, who described Baudrillard as a "visionary". At Nanterre he took up a position as Maître Assistant (Assistant Professor), then Maître de Conférences (Associate Professor), eventually becoming a professor after completing his accreditation, L'Autre par lui-même (The Other by Himself).

In 1970, Baudrillard made the first of his many trips to the United States (Aspen, Colorado), and in 1973, the first of several trips to Kyoto, Japan. He was given his first camera in 1981 in Japan, which led to him becoming a photographer.

In 1986 he moved to IRIS (Institut de Recherche et d'Information Socio-Économique) at the Université de Paris-IX Dauphine, where he spent the latter part of his teaching career. During this time he had begun to move away from sociology as a discipline (particularly in its "classical" form), and, after ceasing to teach full-time, he rarely identified himself with any particular discipline, although he remained linked to academia. During the 1980s and 1990s his books had gained a wide audience, and in his last years he became, to an extent, an intellectual celebrity, being published often in the French- and English-speaking popular press. He nonetheless continued supporting the Institut de Recherche sur l'Innovation Sociale at the Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique and was Satrap at the Collège de Pataphysique. Baudrillard taught at the European Graduate School in Saas-Fee, Switzerland, and collaborated at the Canadian theory, culture, and technology review Ctheory, where he was abundantly cited. He also purportedly participated in the International Journal of Baudrillard Studies (as of 2022 hosted on Bishop's University domain) from its inception in 2004 until his death.

In 1999–2000, his photographs were exhibited at the Maison européenne de la photographie in Paris. In 2004, Baudrillard attended the major conference on his work, "Baudrillard and the Arts", at the Center for Art and Media Karlsruhe in Karlsruhe, Germany.

Personal life

Baudrillard enjoyed baroque music; a favorite composer was Claudio Monteverdi. He also favored rock music such as The Velvet Underground & Nico.

Baudrillard did his writing using "his old typewriter, never at the computer". He has stated that a computer is not "merely a handier and more complex kind of typewriter", whereas with a typewriter he has a "physical relation to writing".

Baudrillard was married twice. He and his first wife Lucile Baudrillard had two children, Gilles and Anne.

In 1970 during his first marriage, Baudrillard met 25-year-old Marine Dupuis when she arrived at the Nanterre where he was a professor. Marine went on to be a media artistic director. They married in 1994 when he was 65.

Diagnosed with cancer in 2005, Baudrillard battled the disease for two years from his apartment on Rue Sainte-Beuve, Paris, dying at the age of 77. Marine Baudrillard curates Cool Memories, an association of Jean Baudrillard's friends.

Key concepts

Baudrillard's published work emerged as part of a generation of French thinkers including: Gilles Deleuze, Jean-François Lyotard, Michel Foucault, Jacques Derrida, and Jacques Lacan who all shared an interest in semiotics, and he is often seen as a part of the post-structuralist philosophical school.

The object value system

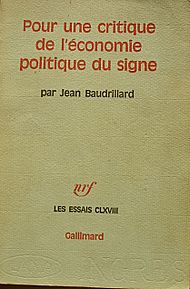

In his early books, such as The System of Objects, For a Critique of the Political Economy of the Sign, and The Consumer Society, Baudrillard's main focus is upon consumerism, and how different objects are consumed in different ways. At this time Baudrillard's political outlook was loosely associated with Marxism (and Situationism), but in these books he differed from Karl Marx in one significant way. For Baudrillard, as for the situationists, it was consumption rather than production that was the main driver of capitalist society.

Baudrillard came to this conclusion by criticising Marx's concept of "use-value." Baudrillard thought that both Marx's and Adam Smith's economic thought accepted the idea of genuine needs relating to genuine uses too easily and too simply. Baudrillard argued, drawing from Georges Bataille, that needs are constructed, rather than innate. He stressed that objects always, "say something" about their users. And this was, for him, why consumption was and remains more important than production: because the "ideological genesis of needs" precedes the production of goods to meet those needs.

He wrote that there are four ways of an object obtaining value. The four value-making processes are:

- The functional value: an object's instrumental purpose (use value). Example: a pen writes; a refrigerator cools.

- The exchange value: an object's economic value. Example: One pen may be worth three pencils, while one refrigerator may be worth the salary earned by three months of work.

- The symbolic value: an object's value assigned by a subject in relation to another subject (i.e., between a giver and receiver). Example: a pen might symbolize a student's school graduation gift or a commencement speaker's gift; or a diamond may be a symbol of publicly declared marital love.

- The sign value: an object's value within a system of objects. Example: a particular pen may, while having no added functional benefit, signify prestige relative to another pen; a diamond ring may have no function at all, but may suggest particular social values, such as taste or class.

Baudrillard's earlier books were attempts to argue that the first two of these values are not simply associated, but are disrupted by the third and, particularly, the fourth. Later, Baudrillard rejected Marxism totally (The Mirror of Production and Symbolic Exchange and Death). But the focus on the difference between sign value (which relates to commodity exchange) and symbolic value (which relates to Maussian gift exchange) remained in his work up until his death. Indeed, it came to play a more and more important role, particularly in his writings on world events.

Simulacra and Simulation

As Baudrillard developed his work throughout the 1980s, he moved from economic theory to mediation and mass communication. Although retaining his interest in Saussurean semiotics and the logic of symbolic exchange (as influenced by anthropologist Marcel Mauss), Baudrillard turned his attention to the work of Marshall McLuhan, developing ideas about how the nature of social relations is determined by the forms of communication that a society employs. In so doing, Baudrillard progressed beyond both Saussure's and Roland Barthes's formal semiology to consider the implications of a historically understood version of structural semiology. According to Kornelije Kvas, "Baudrillard rejects the structuralist principle of the equivalence of different forms of linguistic organization, the binary principle that contains oppositions such as: true-false, real-unreal, center-periphery. He denies any possibility of a (mimetic) duplication of reality; reality mediated through language becomes a game of signs. In his theoretical system all distinctions between the real and the fictional, between a copy and the original, disappear".

Simulation, Baudrillard claims, is the current stage of the simulacrum: all is composed of references with no referents, a hyperreality. Baudrillard argues that this is part of a historical progression. In the Renaissance, the dominant simulacrum was in the form of the counterfeit, where people or objects appear to stand for a real referent that does not exist (for instance, royalty, nobility, holiness, etc.). With the Industrial Revolution, the dominant simulacrum becomes the product, which can be propagated on an endless production line. In current times, the dominant simulacrum is the model, which by its nature already stands for endless reproducibility, and is itself already reproduced.

The end of history and meaning

Throughout the 1980s and 1990s, one of Baudrillard's most common themes was historicity, or, more specifically, how present-day societies use the notions of progress and modernity in their political choices. But as the collapse of the very idea of historical progress. For Baudrillard, the end of the Cold War did not represent an ideological victory; rather, it signaled the disappearance of utopian visions shared between both the political Right and Left.

Within a society subject to and ruled by fast-paced electronic communication and global information networks the collapse of this façade was always going to be, he thought, inevitable. Employing a quasi-scientific vocabulary that attracted the ire of the physicist Alan Sokal, Baudrillard wrote that the speed society moved at had destabilized the linearity of history: "we have the particle accelerator that has smashed the referential orbit of things once and for all."

Russell stated that this "approach to history demonstrates Baudrillard's affinities with the postmodern philosophy of Jean-François Lyotard", who argued that in the late 20th century there was no longer any room for "metanarratives." (The triumph of a coming communism being one such metanarrative.) But, in addition to simply lamenting this collapse of history, Baudrillard also went beyond Lyotard and attempted to analyse how the idea of positive progress was being employed in spite of the notion's declining validity. Baudrillard argued that although genuine belief in a universal endpoint of history, wherein all conflicts would find their resolution, had been deemed redundant, universality was still a notion used in world politics as an excuse for actions. Universal values which, according to him, no one any longer believed universal were and are still rhetorically employed to justify otherwise unjustifiable choices. The means, he wrote, are there even though the ends are no longer believed in, and are employed to hide the present's harsh realities (or, as he would have put it, unrealities). "In the Enlightenment, universalization was viewed as unlimited growth and forward progress. Today, by contrast, universalization is expressed as a forward escape." This involves the notion of "escape velocity" as outlined in The Illusion of the End , which in turn, results in the postmodern fallacy of escape velocity on which the postmodern mind and critical view cannot, by definition, ever truly break free from the all-encompassing "self-referential" sphere of discourse.

See also

In Spanish: Jean Baudrillard para niños

In Spanish: Jean Baudrillard para niños

- Hyper-real Religion

- Reza Negarestani

- The Real

- Code (semiotics)

- Psychoanalytic sociology