Michel Foucault facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Michel Foucault

|

|

|---|---|

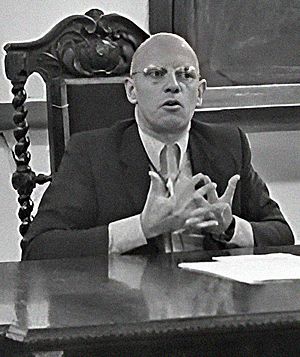

Foucault in 1974

|

|

| Born |

Paul-Michel Foucault

15 October 1926 Poitiers, France

|

| Died | 25 June 1984 (aged 57) Paris, France

|

| Education |

|

|

Notable work

|

|

| Partner(s) | Daniel Defert |

| Region | Western philosophy |

| School |

|

| Institutions |

|

| Doctoral advisor | Georges Canguilhem |

|

Main interests

|

Ethics, historical epistemology, history of ideas, philosophy of literature, philosophy of technology, political philosophy |

|

Notable ideas

|

Biopower (biopolitics), disciplinary institution, discourse analysis, discursive formation, dispositif, épistémè, "archaeology", "Carceral archipelago", "genealogy", governmentality, heterotopia, gaze, limit-experience, power-knowledge, panopticism, subjectivation (assujettissement), parrhesia, epimeleia heautou, visibilités, Regimes of truth |

|

Influenced

|

|

| Signature | |

|

|

Paul-Michel Foucault (UK: /ˈfuːkoʊ/, US: /fuːˈkoʊ/; French: [pɔl miʃɛl fuko]; 15 October 1926 – 25 June 1984) was a French philosopher, historian of ideas, writer, political activist, and literary critic. Foucault's theories primarily address the relationship between power and knowledge, and how they are used as a form of social control through societal institutions. Though often cited as a structuralist and postmodernist, Foucault rejected these labels. His thought has influenced academics, especially those working in communication studies, anthropology, psychology, sociology, criminology, cultural studies, literary theory, feminism, Marxism and critical theory.

Contents

Early life

Early years: 1926–1938

Paul-Michel Foucault was born on 15 October 1926 in the city of Poitiers, west-central France, as the second of three children in a prosperous, socially-conservative, upper-middle-class family. Family tradition prescribed naming him after his father, Paul Foucault (1893–1959), but his mother insisted on the addition of Michel; referred to as Paul at school, he expressed a preference for "Michel" throughout his life.

His father, a successful local surgeon born in Fontainebleau, moved to Poitiers, where he set up his own practice. He married Anne Malapert, the daughter of prosperous surgeon Dr. Prosper Malapert, who owned a private practice and taught anatomy at the University of Poitiers' School of Medicine. Paul Foucault eventually took over his father-in-law's medical practice, while Anne took charge of their large mid-19th-century house, Le Piroir, in the village of Vendeuvre-du-Poitou. Together the couple had three children—a girl named Francine and two boys, Paul-Michel and Denys—who all shared the same fair hair and bright blue eyes. The children were raised to be nominal Catholics, attending mass at the Church of Saint-Porchair, and while Michel briefly became an altar boy, none of the family was devout.

In later life, Foucault revealed very little about his childhood. Describing himself as a "juvenile delinquent", he said his father was a "bully" who sternly punished him. In 1930, two years early, Foucault began his schooling at the local Lycée Henry-IV. There he undertook two years of elementary education before entering the main lycée, where he stayed until 1936. Afterwards, he took his first four years of secondary education at the same establishment, excelling in French, Greek, Latin, and history, though doing poorly at mathematics, including arithmetic.

Teens to young adulthood: 1939–1945

In 1939, the Second World War began, followed by Nazi Germany's occupation of France in 1940. Foucault's parents opposed the occupation and the Vichy regime, but did not join the Resistance. That year, Foucault's mother enrolled him in the Collège Saint-Stanislas, a strict Catholic institution run by the Jesuits. Although he later described his years there as an "ordeal", Foucault excelled academically, particularly in philosophy, history, and literature. In 1942 he entered his final year, the terminale, where he focused on the study of philosophy, earning his baccalauréat in 1943.

Returning to the local Lycée Henry-IV, he studied history and philosophy for a year, aided by a personal tutor, the philosopher Louis Girard. Rejecting his father's wishes that he become a surgeon, in 1945 Foucault went to Paris, where he enrolled in one of the country's most prestigious secondary schools, which was also known as the Lycée Henri-IV. Here he studied under the philosopher Jean Hyppolite, an existentialist and expert on the work of 19th-century German philosopher Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel. Hyppolite had devoted himself to uniting existentialist theories with the dialectical theories of Hegel and Karl Marx. These ideas influenced Foucault, who adopted Hyppolite's conviction that philosophy must develop through a study of history.

University studies: 1946–1951

I wasn't always smart, I was actually very stupid in school ... [T]here was a boy who was very attractive who was even stupider than I was. And to ingratiate myself with this boy who was very beautiful, I began to do his homework for him—and that's how I became smart, I had to do all this work to just keep ahead of him a little bit, to help him. In a sense, all the rest of my life I've been trying to do intellectual things that would attract beautiful boys.

In autumn 1946, attaining excellent results, Foucault was admitted to the élite École Normale Supérieure (ENS), for which he undertook exams and an oral interrogation by Georges Canguilhem and Pierre-Maxime Schuhl to gain entry. Of the hundred students entering the ENS, Foucault ranked fourth based on his entry results, and encountered the highly competitive nature of the institution. Like most of his classmates, he lived in the school's communal dormitories on the Parisian Rue d'Ulm.

He remained largely unpopular, spending much time alone, reading voraciously.

Although studying various subjects, Foucault soon gravitated towards philosophy, reading not only Hegel and Marx but also Immanuel Kant, Edmund Husserl and most significantly, Martin Heidegger. He began reading the publications of philosopher Gaston Bachelard, taking a particular interest in his work exploring the history of science. He graduated from the ENS with a B.A. (licence) in Philosophy in 1948 and a DES (diplôme d'études supérieures, roughly equivalent to an M.A.) in Philosophy in 1949. His DES thesis under the direction of Hyppolite was titled La Constitution d'un transcendental dans La Phénoménologie de l'esprit de Hegel (The Constitution of a Historical Transcendental in Hegel's Phenomenology of Spirit).

In 1948, the philosopher Louis Althusser became a tutor at the ENS. A Marxist, he influenced both Foucault and a number of other students, encouraging them to join the French Communist Party. Foucault did so in 1950, but never became particularly active in its activities, and never adopted an orthodox Marxist viewpoint, rejecting core Marxist tenets such as class struggle. He soon became dissatisfied with the bigotry that he experienced within the party's ranks; he personally faced homophobia and was appalled by the anti-semitism exhibited during the 1952–53 "Doctors' plot" in the Soviet Union. He left the Communist Party in 1953, but remained Althusser's friend and defender for the rest of his life. Although failing at the first attempt in 1950, he passed his agrégation in philosophy on the second try, in 1951. Excused from national service on medical grounds, he decided to start a doctorate at the Fondation Thiers in 1951, focusing on the philosophy of psychology, but he relinquished it after only one year in 1952.

Foucault was also interested in psychology and he attended Daniel Lagache's lectures at the University of Paris, where he obtained a B.A. (licence) in psychology in 1949 and a Diploma in Psychopathology (Diplôme de psychopathologie) from the university's institute of psychology (now Institut de psychologie de l'université Paris Descartes) in June 1952.

Career

Over the following few years, Foucault embarked on a variety of research and teaching jobs. From 1951 to 1955, he worked as a psychology instructor at the ENS at Althusser's invitation. In Paris, he shared a flat with his brother, who was training to become a surgeon, but for three days in the week commuted to the northern town of Lille, teaching psychology at the Université de Lille from 1953 to 1954. Many of his students liked his lecturing style. Meanwhile, he continued working on his thesis, visiting the Bibliothèque Nationale every day to read the work of psychologists like Ivan Pavlov, Jean Piaget and Karl Jaspers. Undertaking research at the psychiatric institute of the Sainte-Anne Hospital, he became an unofficial intern, studying the relationship between doctor and patient and aiding experiments in the electroencephalographic laboratory. Foucault adopted many of the theories of the psychoanalyst Sigmund Freud, undertaking psychoanalytical interpretation of his dreams and making friends undergo Rorschach tests.

Foucault published his first major book, The History of Madness, in (1961). After obtaining work between 1960 and 1966 at the University of Clermont-Ferrand, he produced The Birth of the Clinic (1963) and The Order of Things (1966), publications that displayed his increasing involvement with structuralism, from which he later distanced himself. These first three histories exemplified a historiographical technique Foucault was developing called "archaeology".

From 1966 to 1968, Foucault lectured at the University of Tunis before returning to France, where he became head of the philosophy department at the new experimental university of Paris VIII. Foucault subsequently published The Archaeology of Knowledge (1969). In 1970, Foucault was admitted to the Collège de France, a membership he retained until his death. He also became active in several left-wing groups involved in campaigns against racism and human rights abuses and for penal reform. Foucault later published Discipline and Punish (1975), in which he developed archaeological and genealogical methods that emphasized the role that power plays in society.

Death

Foucault died in Paris on 26 June 1984 from complications of HIV/AIDS; he became the first public figure in France to die from complications of the disease. His partner Daniel Defert founded the AIDES charity in his memory.

Foucault was buried at Vendeuvre-du-Poitou in a small ceremony.

Personal life

Foucault was an atheist. He loved classical music, particularly enjoying the work of Johann Sebastian Bach and Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, and became known for wearing turtleneck sweaters. After his death, Foucault's friend Georges Dumézil described him as having possessed "a profound kindness and goodness", also exhibiting an "intelligence [that] literally knew no bounds". His life-partner Daniel Defert inherited his estate, whose archive was sold in 2012 to the National Library of France for €3.8 million ($4.5 million in April 2021).

Philosophical work

Philosopher Philip Stokes of the University of Reading noted that overall, Foucault's work was "dark and pessimistic". Though it does, however, leave some room for optimism, in that it illustrates how the discipline of philosophy can be used to highlight areas of domination.

Later in his life, Foucault explained that his work was less about analyzing power as a phenomenon than about trying to characterize the different ways in which contemporary society has expressed the use of power to "objectivise subjects".

Literature

In addition to his philosophical work, Foucault also wrote on literature. Death and the Labyrinth: The World of Raymond Roussel, published in 1963 and translated in English in 1986, is Foucault's only book-length work on literature. He described it as "by far the book I wrote most easily, with the greatest pleasure, and most rapidly". Foucault explores theory, criticism, and psychology with reference to the texts of Raymond Roussel, one of the first notable experimental writers. Foucault also gave a lecture responding to Roland Barthes' famous essay "The Death of the Author" titled "What Is an Author?" in 1969, later published in full. According to literary theoretician Kornelije Kvas, for Foucault, "denying the existence of a historical author on account of his/her irrelevance for interpretation is absurd, for the author is a function of the text that organizes its sense".

Power

Foucault's analysis of power comes in two forms: empirical and theoretical. The empirical analyses concern themselves with historical (and modern) forms of power and how these emerged from previous forms of power. Foucault describes three types of power in his empirical analyses: sovereign power, disciplinary power, and biopower.

Foucault is generally critical of "theories" that try to give absolute answers to "everything". Therefore, he considered his own "theory" of power to be closer to a method than a typical "theory". According to Foucault, most people misunderstand power. For this reason, he makes clear that power cannot be completely described as:

- A group of institutions and/or mechanisms whose aim it is for a citizen to obey and yield to the state (a typical liberal definition of power);

- Yielding to rules (a typical psychoanalytical definition of power); or

- A general and oppressing system where one societal class or group oppresses another (a typical feminist or Orthodox Marxist definition of power).

Foucault is not critical of considering these phenomena as "power", but claims that these theories of power cannot completely describe all forms of power. Foucault also claims that a liberal definition of power has effectively hidden other forms of power to the extent that people have uncritically accepted them.

Foucault's power analysis begins on micro-level, with singular "force relations". Richard A. Lynch defines Foucault's concept of "force relation" as "whatever in one's social interactions that pushes, urges or compels one to do something". According to Foucault, force relations are an effect of difference, inequality or unbalance that exists in other forms of relationships (such as economic). Force, and power, is however not something that a person or group "holds" (such as in the sovereign definition of power), instead power is a complex group of forces that comes from "everything" and therefore exists everywhere. That relations of power always result from inequality, difference or unbalance also means that power always has a goal or purpose. Power comes in two forms: tactics and strategies. Tactics is power on the micro-level, which can for example be how a person chooses to express themselves through their clothes. Strategies on the other hand, is power on macro-level, which can be the state of fashion at any moment. Strategies consist of a combination of tactics. At the same time, power is non-subjective according to Foucault. This posits a paradox, according to Lynch, since "someone" has to exert power, while at the same time there can be no "someone" exerting this power. According to Lynch this paradox can be solved with two observations:

- By looking at power as something which reaches further than the influence of single people or groups. Even if individuals and groups try to influence fashion, for example, their actions will often get unexpected consequences.

- Even if individuals and groups have a free choice, they are also affected and limited by their context/situation.

According to Foucault, force relations are constantly changing, constantly interacting with other force relations which may weaken, strengthen or change one another. Foucault writes that power always includes resistance, which means there is always a possibility that power and force relations will change in some way. According to Richard A. Lynch, the purpose of Foucault's work on power is to increase peoples' awareness of how power has shaped their way of being, thinking and acting, and by increasing this awareness making it possible for them to change their way of being, thinking and acting.

Subjectivity

Foucault considered his primary project to be the investigation of how people through history have been made into "subjects". Subjectivity, for Foucault, is not a state of being, but a practice—an active "being". According to Foucault, "the subject" has, by western philosophers, usually been considered as something given; natural and objective. On the contrary, Foucault considers subjectivity to be a construction created by power. Foucault talks of "assujettissement", which is a French term that for Foucault refers to a process where power creates subjects while also oppressing them using social norms. For Foucault "social norms" are standards that people are encouraged to follow, that are also used to compare and define people.

According to Foucault, scientific discourses have played an important role in the disciplinary power system, by classifying and categorizing people, observing their behavior and "treating" them when their behavior has been considered "abnormal". He defines discourse as a form of oppression that does not require physical force. He identifies its production as "controlled, selected, organized and redistributed by a certain number of procedures", which are driven by individuals' aspiration of knowledge to create "rules" and "systems" that translate into social codes. Moreover, discourse creates a force that extends beyond societal institutions and could be found in social and formal fields such as health care systems, educational and law enforcement. The formation of these fields may seem to contribute to social development; however, Foucault warns against discourses' harmful aspects on society.

Sciences such as psychiatry, biology, medicine, economy, psychoanalysis, psychology, sociology, ethnology, pedagogy and criminology have all categorized behaviors as rational, irrational, normal, abnormal, human, inhuman, etc. By doing so, they have all created various types of subjectivity and norms, which are then internalized by people as "truths". People have then adapted their behavior to get closer to what these sciences has labeled as "normal". For example, Foucault claims that psychological observation/surveillance and psychological discourses has created a type of psychology-centered subjectivity, which has led to people considering unhappiness a fault in their psychology rather than in society. This has also, according to Foucault, been a way for society to resist criticism—criticism against society has been turned against the individual and their psychological health.

Self-constituting subjectivity

According to Foucault, subjectivity is not necessarily something that is forced upon people externally—it is also something that is established in a person's relation to themselves. This can, for example, happen when a person is trying to "find themselves" or "be themselves", something Edward McGushin describes as a typical modern activity. In this quest for the "true self", the self is established in two levels: as a passive object (the "true self" that is searched for) and as an active "searcher". The ancient Cynics and the 19th-century philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche posited that the "true self" can only be found by going through great hardship and/or danger. The ancient Stoics and 17th-century philosopher René Descartes, however, argued that the "self" can be found by quiet and solitary introspection. Yet another example is Socrates, who argued that self-awareness can only be found by having debates with others, where the debaters question each other's foundational views and opinions. Foucault, however, argued that "subjectivity" is a process, rather than a state of being. As such, Foucault argued that there is no "true self" to be found. Rather so, the "self" is constituted/created in activities such as the ones employed to "find" the "self". In other words, exposing oneself to hardships and danger does not "reveal" the "true self", according to Foucault, but rather creates a particular type of self and subjectivity. However, according to Foucault the "form" for the subject is in great part already constituted by power, before these self-constituting practices are employed. Schools, workplaces, households, government institutions, entertainment media and the healthcare sector all, through disciplinary power, contribute to forming people into being particular types of subjects.

Freedom

Todd May defines Foucault's concept of freedom as: that which we can do of ourselves within our specific historical context. A condition for this, according to Foucault, is that we are aware of our situation and how it has been created/affected (and is still being affected) by power.

Foucault argues that the forces that have affected people can be changed; people always have the capacity to change the factors that limit their freedom. Freedom is thus not a state of being, but a practice—a way of being in relation to oneself, to others and to the world. Freedom is for Foucault a type of "experimentation" with different "transformations".

Practice of critique

Foucault's "alternative" to the modern subjectivity is described by Cressida Heyes as "critique". For Foucault there are no "good" and "bad" forms of subjectivity, since they are all a result of power relations. In the same way, Foucault argues there are no "good" and "bad" norms. All norms and institutions are at the same time enabling as they are oppressing. Therefore, Foucault argues, it is always crucial to continue with the practice of "critique". Critique is for Foucault a practice that searches for the processes and events that led to our way of being—a questioning of who we "are" and how this "we" came to be. Such a "critical ontology of the present" shows that peoples′ current "being" is in fact a historically contingent, unstable and changeable construction. Foucault emphasizes that since the current way of being is not a necessity, it is also possible to change it. Critique also includes investigating how and when people are being enabled and when they are being oppressed by the current norms and institutions, finding ways to reduce limitations on freedom, resist normalization and develop new and different way of relating to oneself and others. Foucault argues that it is impossible to go beyond power relations, but that it is always possible to navigate power relations in a different way.

Knowledge

Foucault is critical of this "modern" view of knowledge.

Foucault describes two types of "knowledge": "savoir" and "connaissance", two French terms that both can be translated as "knowledge" but with separate meanings for Foucault. By "savoir" Foucault is referring to a process where subjects are created, while at the same time these subjects also become objects for knowledge. An example of this can be seen in criminology and psychiatry. The knowledge about these subjects is "connaissance", while the process in which subjects and knowledge is created is "savoir". A similar term in Foucaults corpus is "pouvoir/savoir" (power/knowledge). With this term Foucault is referring to a type of knowledge that is considered "common sense", but that is created and withheld in that position (as "common sense") by power.

See also

In Spanish: Michel Foucault para niños

In Spanish: Michel Foucault para niños