Isabeau of Bavaria facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Isabeau of Bavaria |

|

|---|---|

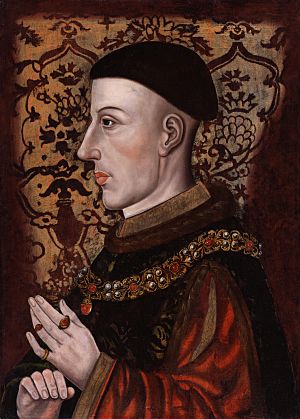

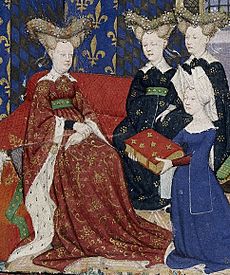

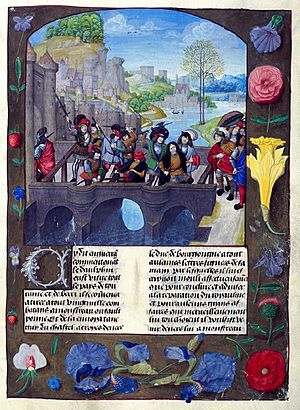

Queen Isabeau receiving Christine de Pizan's Le Livre de la Cité des Dames, c. 1410–1414. Illumination on parchment, British Library

|

|

| Queen consort of France | |

| Tenure | 17 July 1385 – 21 October 1422 |

| Coronation | 23 August 1389, Notre-Dame |

| Born | c. 1370 |

| Died | September 1435 Paris |

| Burial | October 1435 Basilica of St Denis |

| Spouse |

|

| Issue Detail |

Isabella, Queen of England Joan, Duchess of Brittany Marie, Prioress of Poissy Michelle, Duchess of Burgundy Louis, Dauphin of Viennois John, Dauphin of Viennois Catherine, Queen of England Charles VII of France |

| Father | Stephen III, Duke of Bavaria |

| Mother | Taddea Visconti |

Isabeau of Bavaria (or Isabelle; also Elisabeth of Bavaria-Ingolstadt; c. 1370 – September 1435) was Queen of France from 1385 to 1422.

Contents

Lineage and marriage

Isabeau's parents were Duke Stephen III of Bavaria-Ingolstadt and Taddea Visconti, whom he married for a 100,000 ducat dowry. She was most likely born in Munich, where she was baptized as Elisabeth at the Church of Our Lady. She was great-granddaughter to the Wittelsbach Holy Roman Emperor Louis IV. During this period, Bavaria was counted among the most powerful German states and was divided between members of the House of Wittelsbach.

Isabeau's uncle, Duke Frederick of Bavaria-Landshut, suggested in 1383 that she be considered as a bride to King Charles VI of France. Charles was an attractive, physically fit young man, who enjoyed jousting and hunting and was excited to be married.

Charles VI's uncle, Philip the Bold, Duke of Burgundy, thought the proposed marriage ideal to build an alliance with the Holy Roman Empire and against the English. Isabeau's father agreed reluctantly and sent her to France. According to the contemporary chronicler Jean Froissart, Isabeau was 13 or 14 when the match was proposed and about 16 at the time of the marriage in 1385, suggesting a birth date of around 1370.

The couple were married three days later.

Coronation

Isabeau's coronation was celebrated on 23 August 1389 with a lavish ceremonial entry into Paris.

The procession lasted from morning to night. The streets were lined with tableaux vivants displaying scenes from the Crusades, Deësis and the Gates of Paradise. More than a thousand burghers stood along the route; those on one side were dressed in green facing, those on the opposite in red. Isabeau, seven months pregnant, nearly fainted from heat on the first of the five days of festivities. To pay for the extravagant event, taxes were raised in Paris two months later.

Charles' illness

Charles suffered the first of what was to become a lifelong series of bouts of insanity in 1392, falling into a four-day coma afterwards. Few believed he would recover; his uncles, the dukes of Burgundy and Berry, took advantage of his illness and quickly seized power, re-establishing themselves as regents.

The King's sudden onset of insanity was seen by some as a sign of divine anger and punishment, and by others as the result of magic. Modern historians speculate that he may have suffered from the onset of paranoid schizophrenia. The comatose king was returned to Le Mans, where Guillaume de Harsigny—a venerated and well-educated 92-year-old physician—was summoned to treat him. Charles regained consciousness and his fever subsided; he was gradually returned to Paris in September.

Charles suffered a second and more prolonged attack of insanity the following June; it removed him for about six months and set a pattern that would hold for the next three decades as his condition deteriorated. Suggestions were made to replace him with a regent, although there was uncertainty and debate as to whether a regency could assume the full role of a living monarch. When he was incapable of ruling, his brother Orléans, and their cousin John the Fearless, the new Duke of Burgundy, were chief among those who sought to take control of the government.

When Charles became ill in the 1390s, Isabeau was 22; she had three children and had already lost two infants. During the worst of his illness Charles was unable to recognize her and caused her great distress by demanding her removal when she entered his chamber.

Charles' bouts of illness continued unabated until his death. The two may have still felt mutual affection, and Isabeau exchanged gifts and letters with him during his periods of lucidity, but distanced herself during the prolonged attacks of insanity.

Political factions and early diplomatic efforts

Isabeau's life is well documented, most likely because Charles' illness placed her in an unusual position of power. Nevertheless, not much is known about her personal characteristics, and historians even disagree about her appearance. She is variously described as "small and brunette" or "tall and blonde". Despite living in France after her marriage, she spoke with a heavy German accent that never diminished.

Adams describes Isabeau as a talented diplomat who navigated court politics with ease, grace and charisma. Charles had been crowned in 1387, aged 20, attaining sole control of the monarchy. His first acts included the dismissal of his uncles and the reinstatement of the so-called Marmousets—a group of councilors to his father, Charles V—and he gave Orléans more responsibility. Some years later, after Charles' first attack of illness, tensions mounted between Orléans and the royal uncles—Philip the Bold, Duke of Burgundy; John, Duke of Berry; and Louis II, Duke of Bourbon. Forced to assume a greater role in maintaining peace amidst the growing power struggle, which was to persist for many years, Isabeau succeeded in her role as peacekeeper among the various court factions.

During his short-lived recovery in the 1390s, Charles made arrangements for Isabeau to be "principal guardian of the Dauphin", their son, until he reached 13 years of age, giving her additional political power on the regency council. Charles appointed Isabeau co-guardian of their children in 1393, a position shared with the royal dukes and her brother, Louis of Bavaria, while he gave Orléans full power of the regency. In appointing Isabeau, Charles acted under laws enacted by his father, Charles V, which gave the Queen full power to protect and educate the heir to the throne. These appointments separated power between Orléans and the royal uncles, increasing ill-will among the factions. The following year, as Charles' bouts of illness became more severe and prolonged, Isabeau became the leader of the regency council, giving her power over the royal dukes.

Charles trusted Isabeau enough by 1402 to allow her to arbitrate the growing dispute between the Orléanists and Burgundians, and he turned control of the treasury over to her. After Philip the Bold died in 1404 and his son John the Fearless became Duke of Burgundy, the new duke continued the political strife in an attempt to gain access to the royal treasury for Burgundian interests. Orléans and the royal dukes thought John was usurping power for his own interests and Isabeau, at that time, aligned herself with Orléans to protect the interests of the crown and her children.

John the Fearless accused Isabeau and Orléans of fiscal mismanagement and again demanded money for himself, in recompense for the loss of royal revenues after his father's death; an estimated half of Philip the Bold's revenues had come from the French treasury. John raised a force of 1,000 knights and entered Paris in 1405. Orléans hastily retreated with Isabeau to the fortified castle of Melun, with her household and children a day or so behind. John immediately left in pursuit, intercepting the party of chaperones and royal children. He took possession of the Dauphin, and returned him to Paris under control of Burgundian forces; however, the boy's uncle, the duke of Berry, quickly took control of the child at the orders of the Royal Council. At that time, Charles was lucid for about a month and able to help with the crisis. The incident, that came to be known as the enlèvement of the dauphin, almost caused full-scale war, but it was averted. Orléans quickly raised an army while John encouraged Parisians to revolt. They refused, claiming loyalty to the King and his son; Berry was made captain general of Paris and the city's gates were locked. In October, Isabeau became active in mediating the dispute in response to a letter from Christine de Pizan and an ordinance from the Royal Council.

Orléans' assassination and aftermath

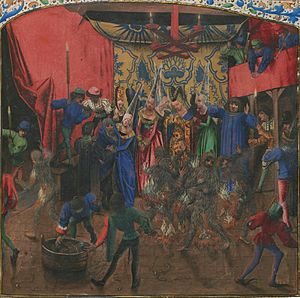

On 23 November 1407, Orléans was assassinated under the orders of John the Fearless. John first denied involvement in the assassination, but quickly admitted that the act was done for the Queen's honor. His royal uncles, shocked at his confession, forced him to leave Paris while the Royal Council attempted a reconciliation between the Houses of Burgundy and Orléans.

In March 1408, Jean Petit presented a lengthy and well-attended justification at the royal palace before a large courtly audience. Petit argued convincingly that in the King's absence Orléans became a tyrant, practiced sorcery and necromancy, and was driven by greed. John should be exonerated, Petit argued, because he had defended the King and monarchy by assassinating Orléans. Charles, "insane during the oration", was convinced by Petit's argument and pardoned John the Fearless, only to rescind the pardon in September.

Violence again broke out after the assassination; Isabeau had troops patrol Paris and, to protect the Dauphin Louis, Duke of Guyenne, she again left the city for Melun. In August she staged an entry to Paris for the Dauphin, and early in the new year, Charles signed an ordinance giving the 13-year-old the power to rule in the Queen's absence. During these years, Isabeau's greatest concern was the Dauphin's safety as she prepared him to take up the duties of the King; she formed alliances to further those aims. At this point, the Queen and her influence were still crucial to the power struggle. Physical control of Isabeau and her children became important to both parties and she was frequently forced to change sides, for which she was criticized and called unstable. She joined the Burgundians from 1409 to 1413, then switched sides to form an alliance with the Orléanists from 1413 to 1415.

At the Peace of Chartres in March 1409, John the Fearless was reinstated to the Royal Council after a public reconciliation with Orléans' son, Charles, Duke of Orléans, at Chartres Cathedral, although the feuding continued. In December that year, Isabeau bestowed the tutelle (guardianship of the Dauphin) upon John the Fearless, made him the master of Paris, and allowed him to mentor the Dauphin. At that point, the Duke essentially controlled the Dauphin and Paris and was popular in the city because of his opposition to taxes levied by Isabeau and Orléans. Isabeau's actions with respect to John the Fearless angered the Armagnacs, who in the fall of 1410 marched to Paris to "rescue" the Dauphin from the Duke's influence. At that time, members of the University of Paris, Jean Gerson in particular, proposed that all feuding members of the Royal Council step down and be immediately removed from power.

To defuse tension with the Burgundians, a second double marriage was arranged in 1409. Isabeau's daughter Michelle married Philip the Good, son of John the Fearless; Isabeau's son, the Dauphin Louis, married John's daughter Margaret. Before the wedding, Isabeau negotiated a treaty with John the Fearless in which she clearly defined family hierarchy and her position in relation to the throne.

Civil war

Despite Isabeau's efforts to keep the peace, the Armagnac–Burgundian Civil War broke out in 1411. King Henry V of England took advantage of the internal strife in France, invading the northwest coast, and in 1415, he delivered a crushing defeat to the French at Agincourt. Nearly an entire generation of military leaders died or were taken prisoner in a single day. John, still feuding with the royal family and the Armagnacs, remained neutral as Henry V went on to conquer towns in northern France.

In December 1415, Dauphin Louis died suddenly at age 18 of illness, leaving Isabeau's political status unclear.

Another shift in power occurred when Isabeau's sixth and last son, Charles, age 14, became Dauphin. He was betrothed to Armagnac's daughter Marie of Anjou and favored the Armagnacs. At that time, Armagnac imprisoned Isabeau in Tours, confiscating her personal property (clothing, jewels and money), dismantling her household, and separating her from the younger children as well as her ladies-in-waiting. She secured her freedom in November with the help of the Duke of Burgundy. Accounts of her release vary: Monstrelet writes that Burgundy "delivered" her to Troyes, and Pintoin that the Duke negotiated Isabeau's release to gain control of her authority. Isabeau maintained her alliance with Burgundy from that period until the Treaty of Troyes in 1420.

Isabeau at first assumed the role of sole regent but in January 1418 yielded her position to John the Fearless. Together Isabeau and John abolished parliament (Chambre des comptes) and turned to securing control of Paris and the King. John took control of Paris by force on 28 May 1418, slaughtering Armagnacs. The Dauphin fled the city. According to Pintoin's chronicle, the Dauphin refused Isabeau's invitation to join her in an entry to Paris. She entered the city with John on 14 July.

Shortly after he assumed the title of Dauphin, Charles negotiated a truce with John in Pouilly. Charles then requested a private meeting with John, on 10 September 1419 at a bridge in Montereau, promising his personal guarantee of protection. The meeting, however, was a ploy to assassinate John. His father, King Charles, immediately disinherited his son. The civil war ended after John's death. The Dauphin's actions fueled more rumor about his legitimacy, and his disinheritance set the stage for the Treaty of Troyes.

Treaty of Troyes and later years

By 1419, Henry V had occupied much of Normandy and demanded an oath of allegiance from the residents. The new Duke of Burgundy, Philip the Good, allied with the English, putting enormous pressure on France and Isabeau, who remained loyal to the King. In 1420, Henry sent an emissary to confer with the Queen, after which, according to Adams, Isabeau "ceded to what must have been a persuasively posed argument by Henry V's messenger". France had effectively been left without an heir to the throne, even before the Treaty of Troyes. Charles VI had disinherited the Dauphin, whom he considered responsible for "breaking the peace for his involvement in the assassination of the duke of Burgundy"; he wrote in 1420 of the Dauphin that he had "rendered himself unworthy to succeed to the throne or any other title". Charles of Orléans, next in line as heir under Salic law, had been taken prisoner at the Battle of Agincourt and was kept in captivity in London.

In the absence of an official heir to the throne, Isabeau accompanied King Charles to sign the Treaty of Troyes in May 1420; Gibbons writes that the treaty "only confirmed [the Dauphin's] outlaw status". The King's illness prevented him from appearing at the signing of the treaty, forcing Isabeau to stand in for him, which according to Gibbons gave her "perpetual responsibility in having sworn away France". For many centuries, Isabeau stood accused of relinquishing the crown because of the Treaty. Under the terms of the Treaty, Charles remained as King of France but Henry V, who married Charles' and Isabeau's daughter, Catherine, kept control of the territories he conquered in Normandy, would govern France with the Duke of Burgundy, and was to be Charles' successor. Isabeau was to live in English-controlled Paris.

Charles VI died in October 1422. As Henry V had died earlier the same year, his infant son by Catherine, Henry VI, was proclaimed King of France, according to the terms of the Treaty of Troyes, with the Duke of Bedford acting as regent. Rumors circulated about Isabeau again; some chronicles describe her living in a "degraded state". According to Tuchman, Isabeau had a farmhouse built in St. Ouen where she looked after livestock.

Isabeau was removed from political influence and retired to live in the Hôtel Saint-Pol with her brother's second wife, Catherine of Alençon. She was accompanied by her ladies-in-waiting Amelie von Orthenburg and Madame de Moy, the latter of whom had traveled from Germany and had stayed with her as dame d'honneur since 1409. Isabeau possibly died there in late September 1435. Her death and funeral were documented by Jean Chartier (member of St Denis Abbey), who may well have been an eyewitness.

Reputation and legacy

Isabeau was dismissed by historians in the past as a weak and indecisive leader. Modern historians now see her as taking an unusually active leadership role for a queen of her period, forced to take responsibility as a direct result of Charles' illness.

After the onset of the King's illness, a common belief was that Charles' mental illness and inability to rule were due to Isabeau's witchcraft; as early as the 1380s, rumors spread that the court was steeped in sorcery. In 1397 Orléans' wife, Valentina Visconti, was forced to leave Paris because she was accused of using magic. The court of the "mad king" attracted magicians with promises of cures who were often used as political tools by the various factions. Lists of people accused of bewitching Charles were compiled, with Isabeau and Orléans both listed.

Isabeau was accused of indulging in extravagant and expensive fashions, jewel-laden dresses and elaborate braided hairstyles coiled into tall shells, covered with wide double hennins that, reportedly, required widened doorways to pass through. She was accused of leading France into a civil war because of her inability to support a single faction; she was described as an "empty headed" German.

Patronage

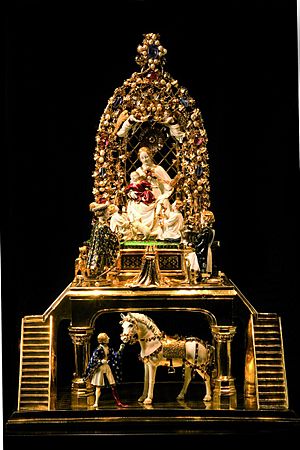

Like many of the Valois, Isabeau was an appreciative art collector. She loved jewels and was responsible for the commissions of particularly lavish pieces of ronde-bosse — a newly developed technique of making enamel-covered gold pieces. Documentation suggests she commissioned several fine pieces of tableaux d'or from Parisian goldsmiths.

In 1404, Isabeau gave Charles a spectacular ronde-bosse, known as the Little Golden Horse Shrine, (or Goldenes Rössl), now held in a convent church in Altötting, Bavaria. Contemporary documents identify the statuette as a New Year's gift—an étrennes—a Roman custom Charles revived to establish rank and alliances during the period of factionalism and war. With the exception of manuscripts, the Little Golden Horse is the single surviving documented étrennes of the period. Weighing 26 pounds (12 kg), the gold piece is encrusted with rubies, sapphires and pearls. It depicts Charles kneeling on a platform above a double set of stairs, presenting himself to the Virgin Mary and child Jesus, who are attended by John the Evangelist and John the Baptist. A jewel encrusted trellis or bower is above; beneath stands a squire holding the golden horse. Isabeau also exchanged New Year's gifts with the Duke of Berry; one extant piece is the ronde-bosse statuette Saint Catherine.

Medieval author Christine de Pizan solicited the Queen's patronage at least three times. In 1402, she sent a compilation of her literary argument Querelle du Roman de la Rose—in which she questions the concept of courtly love—with a letter exclaiming "I am firmly convinced the feminine cause is worthy of defense. This I do here and have done with my other works." In 1410 and again in 1411, Pizan solicited the Queen, presenting her in 1414 an illuminated copy of her works. In The Book of the City of Ladies, Pizan praised Isabeau lavishly, and again in the illuminated collection, The Letter of Othea, which scholar Karen Green believes for de Pizan is "the culmination of fifteen years of service during which Christine formulated an ideology that supported Isabeau's right to rule as regent in this time of crisis."

Isabeau showed great piety, essential for a queen of her period. During her lifetime, and in her will, she bequeathed property and personal possessions to Notre Dame, St. Denis, and the convent in Poissy.

Children

The birth of each of Isabeau's 12 children is well chronicled; even the decoration schemes of the rooms in which she gave birth are described. She had six sons and six daughters. The first son, born in 1386, died as an infant and the last, Philip, born in 1407, lived a single day. Three others died young with only her youngest son, Charles VII, living to adulthood. Five of the six daughters survived; four were married and one, Marie (1393–1438), was sent at age four to be raised in a convent, where she became prioress.

Her first son, Charles (b. 1386), the first Dauphin, died in infancy. A daughter, Joan, born two years later, lived until 1390. The second daughter, Isabella (1389-1409) was married at age seven to Richard II of England and after his death to Charles, Duke of Orléans. The third daughter, another Joan (1391–1433), who lived to age 42, married John VI, Duke of Brittany. The fourth daughter, Michelle (1395–1422), first wife to Philip the Good, died childless at age 27. Catherine of Valois, Queen of England (1401–1437), married Henry V of England; on his death she took Sir Owen Tudor as her second husband.

Of her remaining sons, the second Dauphin was another Charles (1392–1401), who died at age eight of a "wasting illness". Louis, Duke of Guyenne (1397-1415), was the third Dauphin, married to Margaret of Nevers, who died at age 18. John, Duke of Touraine (1398-1417), the fourth Dauphin, the first husband of Jacqueline, Countess of Hainaut, died without issue, also at the age of 18. The fifth Dauphin, yet another Charles (1403-1461), became King Charles VII of France after his father's death. He was married to Marie of Anjou. Her last son, Philip, died in infancy in the year 1407.

According to modern historians, Isabeau stayed in close proximity to the children during their childhood, had them travel with her, bought them gifts, wrote letters, bought devotional texts, and arranged for her daughters to be educated. She resisted separation and reacted against having her sons sent to other households to live (as was the custom at the time). Pintoin records that she was dismayed at the marriage contract that stipulated her third surviving son, John, be sent to live in Hainaut. She maintained relationships with her daughters after their marriages, writing letters to them frequently. She sent them out of Paris during an outbreak of plague, staying behind herself with the youngest infant, John, too young to travel.

-

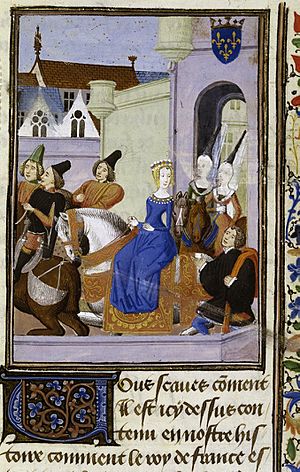

Miniature from a late 15th-century manuscript of Froissart's Chronicles showing Isabella's marriage to Richard II of England

-

Joan of France, shown in a late 17th-century or early 18th-century drawing, married John VI, Duke of Brittany

-

Michelle of Valois, shown here in a white hennin (from the center panel of a Flemish triptych), was first wife to Philip the Good

-

Catherine of Valois, meeting Henry V of England, shown in a 19th-century woodcut, printed by Edmund Evans

-

Charles VII of France shown in a mid-15th-century portrait by Jean Fouquet

Ancestry

| Ancestors of Isabeau of Bavaria | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

See also

In Spanish: Isabel de Baviera-Ingolstadt para niños

In Spanish: Isabel de Baviera-Ingolstadt para niños