Indus Valley civilization facts for kids

|

|

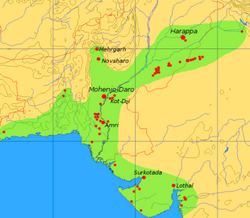

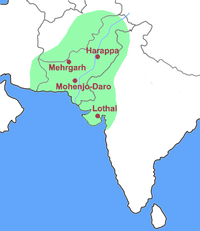

| Geographical range | Basins of the Indus River, Pakistan and the seasonal Ghaggar-Hakra river, northwest India and eastern Pakistan. |

|---|---|

| Period | Bronze Age South Asia |

| Dates | c. 3300 – c. 1300 BCE |

| Type site | Harappa |

| Major sites | Harappa, Mohenjo-daro (27°19′45″N 68°08′20″E / 27.32917°N 68.13889°E), Dholavira, Ganeriwala, and Rakhigarhi |

| Preceded by | Mehrgarh |

| Followed by | Painted Grey Ware culture Cemetery H culture |

The Indus Valley civilization was a Bronze Age civilization(3300–1300 BC; mature period 2700-1700 BC)

The civilization was in the subcontinent. It was discovered by archaeologists in the 1880s. It developed along the Indus River and the Ghaggar-Hakra River and even that areas are now in modern Pakistan, north-west India and Afghanistan. The civilization started during the Bronze Age and the height of its development was between 2500 BC and 1500 BC. Including the civilizations directly before and after, it may have lasted from the 33rd to the 14th century BC.

The Indus Valley civilization covered a large area – from Balochistan (Pakistan) to Gujarat (Republic of India). The first city to be discovered by excavation (digging up) was Harappa and therefore this civilization is also known as 'Harappan Civilization'.

They were good builders. The ruins of the site shows skillful design. Their buildings had two or sometimes more stories. The bathrooms were attached to the rooms. One of the unique features of the city was its elaborate drainage system. A brick-lined drainage channel flowed alongside every street. Removable bricks were placed at regular intervals for easy cleaning and inspection.

The harappan traders used seals on the knots of the sacks to be transported to make sure that they were not opened during the journey. Nobody knows how to read their writing system.

In 1842 Charles Masson wrote a book that mentioned the sites of Indus Valley Civilisation. Few people paid attention. Later, in 1921-22, John Marshall organised the first archaeological dig at Harappa.

Contents

Discovery and history of excavation

The ruins of Harappa were first described in 1842 by Charles Masson in his Narrative of Various Journeys in Balochistan, Afghanistan, and the Punjab, where locals talked of an ancient city extending "thirteen cosses" (about 25 miles).

In 1856, General Alexander Cunningham, later director general of the archaeological survey of northern India, visited Harappa where the British engineers John and William Brunton were laying the East Indian Railway Company line connecting the cities of Karachi and Lahore. They were told of an ancient ruined city near the lines. Visiting the city, he found it full of hard well-burnt bricks, and, "convinced that there was a grand quarry for the ballast I wanted", the city of Brahminabad was reduced to ballast. A few months later, further north, John's brother William Brunton's "section of the line ran near another ruined city, bricks from which had already been used by villagers in the nearby village of Harappa at the same site. These bricks now provided ballast along 93 miles (150 km) of the railroad track running from Karachi to Lahore".

In 1872–75 Alexander Cunningham published the first Harappan seal. It was half a century later, in 1912, that more Harappan seals were discovered prompting an excavation campaign under Sir John Hubert Marshall in 1921–22 and resulting in the discovery of the civilisation at Harappa.

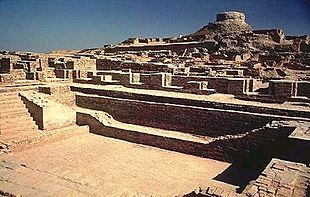

By 1931, much of Mohenjo-Daro had been excavated.

In 2010, heavy floods hit Haryana in India and damaged the archaeological site of Jognakhera, where ancient copper smelting furnaces were found dating back almost 5,000 years. The Indus Valley Civilization site was hit by almost 10 feet of water as the Sutlej Yamuna link canal overflowed.

Geography

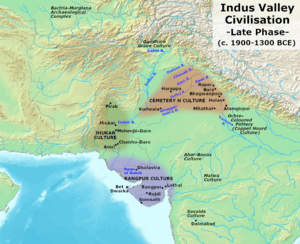

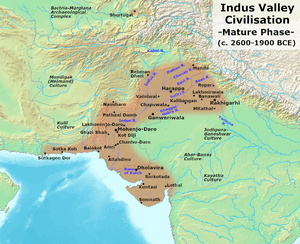

The Indus Valley Civilization encompassed most of Pakistan and parts of northwestern India, and Afghanistan, extending from Pakistani Balochistan in the west to Uttar Pradesh in the east, northeastern Afghanistan to the north and Maharashtra to the south.

Indus Valley sites have been found most often on rivers, but also on the ancient seacoast, for example, Balakot, and on islands, for example, Dholavira.

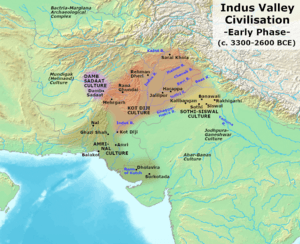

Early Harappan

The Early Harappan Ravi Phase, named after the nearby Ravi River, lasted from circa 3300 BCE until 2800 BCE. It is related to the Hakra Phase, identified in the Ghaggar-Hakra River Valley to the west, and predates the Kot Diji Phase (2800–2600 BCE, Harappan 2), named after a site in northern Sindh, Pakistan, near Mohenjo Daro. The earliest examples of the Indus script dated to 3rd millennium BC.

Latest discoveries from Bhirrana, Haryana, in India since 2012 onwards, by archaeologist K. N. Dikshit indicate that Hakra ware from this area dates from as early as 7500 BCE, which makes Bhirrana the oldest site in Indus Valley civilization.

Trade networks linked this culture with related regional cultures and distant sources of raw materials, including lapis lazuli and other materials for bead-making. Villagers had, by this time, domesticated numerous crops, including peas, sesame seeds, dates, and cotton, as well as animals, including the water buffalo. Early Harappan communities turned to large urban centres by 2600 BCE, from where the mature Harappan phase started.

Mature Harappan

By 2600 BCE, the Early Harappan communities had been turned into large urban centres. Such urban centres include Harappa, Ganeriwala, Mohenjo-Daro in modern day Pakistan, and Dholavira, Kalibangan, Rakhigarhi, Rupar, and Lothal in modern day India. In total, more than 1,052 cities and settlements have been found, mainly in the general region of the Indus Rivers and their tributaries.

Cities

A sophisticated and technologically advanced urban culture is evident in the Indus Valley Civilization making them the first urban centres in the region. The quality of the cities suggests they used urban planning and placed a high priority on hygiene.

As seen in Harappa, Mohenjo-Daro and the recently partially excavated Rakhigarhi, this urban plan included the world's first known urban sanitation systems. Within the city, individual homes or groups of homes obtained water from wells. From a room that appears to have been set aside for bathing, waste water was directed to covered drains, which lined the major streets. Houses opened only to inner courtyards and smaller lanes.

The ancient Indus systems of sewerage and drainage that were developed in cities throughout the Indus region were far more advanced than any found in contemporary urban sites in the Middle East and even more efficient than those in many areas of Pakistan and India today.

The advanced architecture of the Harappans is shown by their impressive dockyards, granaries, warehouses, brick platforms, and protective walls. The massive walls of Indus cities most likely protected the Harappans from floods and may have dissuaded military conflicts.

The purpose of the citadel remains debated. In sharp contrast to this civilisation's contemporaries, Mesopotamia and Ancient Egypt, no large monumental structures were built. There is no evidence of palaces or temples—or of kings, armies, or priests.

Most city dwellers appear to have been traders or artisans, who lived with others pursuing the same occupation in well-defined neighbourhoods. Materials from distant regions were used in the cities for constructing seals, beads and other objects. Among the artefacts discovered were beautiful glazed faïence beads. Steatite seals have images of animals, people (perhaps gods), and other types of inscriptions, including the yet un-deciphered writing system of the Indus Valley Civilization. Some of the seals were used to stamp clay on trade goods and most probably had other uses as well.

The prehistory of Indo-Iranian borderlands shows a steady increase over time in the number and density of settlements. The population increased in Indus plains because of hunting and gathering.

Technology

The people of the Indus Civilization achieved great accuracy in measuring length, mass, and time. They were among the first to develop a system of uniform weights and measures.

Harappans evolved some new techniques in metallurgy and produced copper, bronze, lead, and tin. The engineering skill of the Harappans was remarkable, especially in building docks.

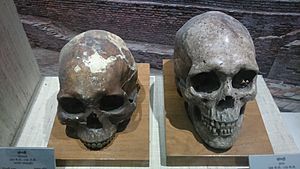

In 2001, archaeologists studying the remains of two men from Mehrgarh, Pakistan, made the discovery that the people of the Indus Valley Civilization, from the early Harappan periods, had knowledge of dentistry.

A touchstone bearing gold streaks was found in Banawali, which was probably used for testing the purity of gold (such a technique is still used in some parts of India).

Arts and crafts

Various sculptures, seals, pottery, gold jewellery, and anatomically detailed figurines in terracotta, bronze, and steatite have been found at excavation sites.

A number of gold, terracotta and stone figurines of girls in dancing poses reveal the presence of some dance form. Also, these terracotta figurines included cows, bears, monkeys, and dogs.

Many crafts "such as shell working, ceramics, and agate and glazed steatite bead making" were used in the making of necklaces, bangles, and other ornaments.

Some make-up and toiletry items were found. Terracotta female figurines were found (ca. 2800–2600 BCE) which had red colour applied to the "manga" (line of partition of the hair).

Seals have been found at Mohenjo-Daro depicting a figure standing on its head, and another sitting cross-legged in what some call a yoga-like pose

This figure, sometimes known as a Pashupati, has been variously identified. Sir John Marshall identified a resemblance to the Hindu god, Shiva.

A harp-like instrument depicted on an Indus seal and two shell objects found at Lothal indicate the use of stringed musical instruments.

Trade and transportation

The Indus civilisation's economy appears to have depended significantly on trade, which was facilitated by major advances in transport technology.

The IVC may have been the first civilisation to use wheeled transport. These advances may have included bullock carts that are identical to those seen throughout South Asia today, as well as boats.

Most of these boats were probably small, flat-bottomed craft, perhaps driven by sail, similar to those one can see on the Indus River today; however, there is secondary evidence of sea-going craft. Archaeologists have discovered a massive, dredged canal and what they regard as a docking facility at the coastal city of Lothal in western India (Gujarat state). An extensive canal network, used for irrigation, has also been discovered.

Judging from the dispersal of Indus civilisation artefacts, the trade networks integrated a huge area, including portions of Afghanistan, the coastal regions of Persia, northern and western India, and Mesopotamia. Studies of tooth enamel from individuals buried at Harappa suggest that some residents had migrated to the city from beyond the Indus valley. There is some evidence that trade contacts extended to Crete and possibly to Egypt.

There was an extensive maritime trade network operating between the Harappan and Mesopotamian civilisations as early as the middle Harappan Phase. Such long-distance sea trade became feasible with the innovative development of plank-built watercraft, equipped with a single central mast supporting a sail of woven rushes or cloth.

Writing system

Between 400 and as many as 600 distinct Indus symbols have been found on seals, small tablets, ceramic pots and more than a dozen other materials, including a "signboard" that apparently once hung over the gate of the inner citadel of the Indus city of Dholavira.

Typical Indus inscriptions are no more than four or five characters in length, most of which are tiny; the longest on a single surface, which is less than 1 inch (2.54 cm) square, is 17 signs long; the longest on any object (found on three different faces of a mass-produced object) has a length of 26 symbols.

In a 2009 study by P. N. Rao et al. published in Science, computer scientists, comparing the pattern of symbols to various linguistic scripts and non-linguistic systems, including DNA and a computer programming language, found that the Indus script's pattern is closer to that of spoken words.

The messages on the seals are too short to be decoded by a computer.

Collapse

Around 1800 BCE, signs of a gradual decline began to emerge, and by around 1700 BCE, most of the cities were abandoned.

Images for kids

-

Excavated ruins of Mohenjo-daro, Sindh province, Pakistan, showing the Great Bath in the foreground. Mohenjo-daro, on the right bank of the Indus River, is a UNESCO World Heritage Site, the first site in South Asia to be so declared.

-

Miniature votive images or toy models from Harappa, c. 2500 BCE. Terracotta figurines indicate the yoking of zebu oxen for pulling a cart and the presence of the chicken, a domesticated jungle fowl.

-

Alexander Cunningham, the first director general of the Archaeological Survey of India (ASI), interpreted a Harappan stamp seal in 1875.

-

John Marshall, the director-general of the ASI from 1902 to 1928, who oversaw the excavations in Harappa and Mohenjo-daro, shown in a 1906 photograph

-

Terracotta boat in the shape of a bull, and female figurines. Kot Diji period (c. 2800–2600 BC).

-

Harappan weights found in the Indus Valley, (National Museum, New Delhi)

-

Archaeological discoveries suggest that trade routes between Mesopotamia and the Indus were active during the 3rd millennium BCE, leading to the development of Indus–Mesopotamia relations.

-

Boat with direction-finding birds to find land. Model of Mohenjo-daro tablet, 2500–1750 BCE.(National Museum, New Delhi). Flat-bottomed river row-boats appear in two Indus seals, but their seaworthiness is debatable.

-

Ten Indus characters from the northern gate of Dholavira, dubbed the Dholavira signboard

-

Swastika seals of Indus Valley civilisation in British Museum

-

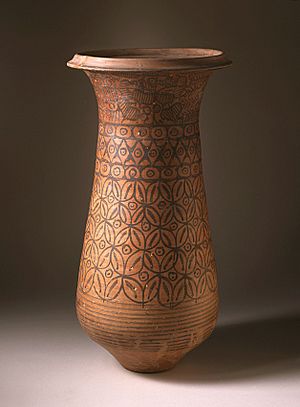

Painted pottery urns from Harappa (Cemetery H culture, c. 1900–1300 BCE), National Museum, New Delhi

-

Impression of a cylinder seal of the Akkadian Empire, with label: "The Divine Sharkalisharri Prince of Akkad, Ibni-Sharrum the Scribe his servant". The long-horned buffalo is thought to have come from the Indus Valley, and testifies to exchanges with Meluhha, the Indus Valley civilisation. Circa 2217–2193 BCE. Louvre Museum.

-

Cubical weights, standardised throughout the Indus cultural zone; 2600-1900 BC; chert; British Museum (London)

-

Mohenjo-daro beads; 2600-1900 BC; carnelian and terracotta; British Museum

-

Reclining mouflon; 2600–1900 BC; marble; length: 28 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York City)

-

Male dancing torso; 2400-1900 BC; limestone; height: 9.9 cm; National Museum (New Delhi)

-

Seal with two-horned bull and inscription; 2010 BC; steatite; overall: 3.2 x 3.2 cm; Cleveland Museum of Art (Cleveland, Ohio, US)

See also

In Spanish: Civilización del valle del Indo para niños

In Spanish: Civilización del valle del Indo para niños