History of Alaska facts for kids

|

| History of Alaska |

|---|

| Prehistory |

| Russian America (1733–1867) |

| Department of Alaska (1867–1884) |

| District of Alaska (1884–1912) |

| Territory of Alaska (1912–1959) |

| State of Alaska (1959–present) |

| Other topics |

The history of Alaska dates back to the Upper Paleolithic period (around 14,000 BC), when foraging groups crossed the Bering land bridge into what is now western Alaska. At the time of European contact by the Russian explorers, the area was populated by Alaska Native groups. The name "Alaska" derives from the Aleut word Alaxsxaq (also spelled Alyeska), meaning "mainland" (literally, "the object toward which the action of the sea is directed").

The U.S. purchased Alaska from Russia in 1867. In the 1890s, gold rushes in Alaska and the nearby Yukon Territory brought thousands of miners and settlers to Alaska. Alaska was granted territorial status in 1912 by the United States of America.

In 1942, two of the outer Aleutian Islands—Attu and Kiska—were occupied by the Japanese during World War II and their recovery for the U.S. became a matter of national pride. The construction of military bases contributed to the population growth of some Alaskan cities.

Alaska was granted U.S. statehood on January 3, 1959.

In 1964, the massive "Good Friday earthquake" killed 131 people and leveled several villages.

The 1968 discovery of oil at Prudhoe Bay and the 1977 completion of the Trans-Alaska Pipeline led to an oil boom. In 1989, the Exxon Valdez hit a reef in Prince William Sound, spilling between 11 to 34 million US gallons (42,000 to 129,000 m3) of crude oil over 1,100 miles (1,800 km) of coastline. Today, the battle between philosophies of development and conservation is seen in the contentious debate over oil drilling in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge.

Contents

Prehistory of Alaska

Paleolithic families moved into northwestern North America sometime between 16,000 and 10,000 BC across the Bering land bridge in Alaska. Alaska became populated by the Inuit and a variety of Native American groups. Today, early Alaskans are divided into several main groups: the Southeastern Coastal Indians (the Tlingit, Haida, and Tsimshian), the Athabascans, the Aleut, and the two groups of Eskimos, the Inupiat and the Yup'ik.

The coastal migrants from Asia were probably the first wave of humans to cross the Bering Land Bridge in western Alaska, and many of them initially settled in the interior of what is now Canada. The Tlingit were the most numerous of this group, claiming most of the coastal Panhandle by the time of European contact and are the northernmost of the group of advanced cultures of the Pacific Northwest Coast renowned for its complex art and political systems and the ceremonial and legal system known as the potlatch. The southern portion of Prince of Wales Island was settled by the Haidas fleeing persecution by other Haidas from the Queen Charlotte Islands (now part of British Columbia). The Aleuts settled the islands of the Aleutian chain approximately 10,000 years ago.

Cultural and subsistence practices varied widely among native groups, who were spread across vast geographical distances.

18th century

Early Russian settlement

On some islands and parts of the Alaskan peninsula, groups of traders had been capable of relatively peaceful coexistence with the local inhabitants. Other groups could not manage the tensions and perpetrated exactions. Hostages were taken, individuals were enslaved, families were split up, and other individuals were forced to leave their villages and settle elsewhere. In addition, eighty percent of the Aleut population was destroyed by Old World diseases, against which they had no immunity, during the first two generations of Russian contact.

In 1784, Grigory Ivanovich Shelikhov arrived in Three Saints Bay on Kodiak Island, operating the Shelikhov-Golikov Company. Shelikhov and his men killed hundreds of indigenous Koniag, then founded the first permanent Russian settlement in Alaska on the island's Three Saints Bay. By 1788 a number of Russian settlements had been established by Shelikhov and others over a large region, including the mainland areas around Cook Inlet.

The Russians had gained control of the habitats of the most valuable sea otters, the Kurilian-Kamchatkan and Aleutian sea otters. Their fur was thicker, glossier, and blacker than those of sea otters on the Pacific Northwest Coast and California. The Russians, therefore, advanced to the Northwest Coast only after the superior varieties of sea otters were depleted, around 1788.

In 1795 Alexandr Baranov, who had been hired in 1790 to manage Shelikhov's fur enterprise, sailed into Sitka Sound, claiming it for Russia. Hunting parties arrived in the following years and by 1800 three-quarters of Russian America's sea otter skins were coming from the Sitka Sound area. In July 1799 Baranov returned on the brig Oryol and established the settlement of Arkhangelsk. It was destroyed by Tlingits in 1802 but rebuilt nearby in 1804 and given the name Novo-Arkhangelsk (New Archangel). It soon become the primary settlement and colonial capital of Russian America. After the Alaska Purchase, it was renamed Sitka, the first capital of Alaska Territory.

Missionary activity

The Russian Orthodox religion (with its rituals and sacred texts, translated into Aleut at a very early stage) had been informally introduced, in the 1740s–1780s, by the fur traders. During his settlement of Three Saints Bay in 1784, Shelikov introduced the first resident missionaries and clergymen. This missionary activity would continue into the 19th century, ultimately becoming the most visible trace of the Russian colonial period in contemporary Alaska.

Spanish claims

Spanish claims to Alaska dated to the papal bull of 1493, but never involved colonization, forts, or settlements. Instead there were various naval expeditions to explore the region and claim it for Spain. In 1775, Bruno de Hezeta led an expedition; The Sonora, under Bodega y Quadra, ultimately reached latitude 58° north, entered Sitka Sound and formally claimed the region for Spain. The 1779 expedition of Ignacio de Arteaga and Bodega y Quadra reached Port Etches on Hinchinbrook Island, and entered Prince William Sound. They reached a latitude of 61° north, the most northern point obtained by Spain.

Britain's presence

British settlements at the time in Alaska consisted of a few scattered trading outposts, with most settlers arriving by sea. Captain James Cook, midway through his third and final voyage of exploration in 1778, sailed along the west coast of North America aboard HMS Resolution, from then-Spanish California all the way to the Bering Strait. During the trip, he discovered what came to be known as Cook Inlet (named in honor of Cook in 1794 by George Vancouver, who had served under his command) in Alaska. The Bering Strait proved to be impassable, although the Resolution and its companion ship HMS Discovery made several attempts to sail through it. The ships left the straits to return to Hawaii in 1779.

Cook's expedition spurred the British to increase their sailings along the northwest coast, following in the wake of the Spanish. Alaska-based posts owned by the Hudson's Bay Company, operated at Fort Yukon, on the Yukon River, Fort Durham (aka Fort Taku) at the mouth of the Taku River, and Fort Stikine, near the mouth of the Stikine River (associated with Wrangell throughout the early 19th century).

19th century

Later Russian settlement and the Russian-American Company (1799–1867)

The Russo-American Treaty of 1824, which banned American merchants above 54° 40' north latitude, was widely ignored and the Russians' hold on Alaska weakened further.

At the height of Russian America, the Russian population reached 700.

Although the mid–19th century were not a good time for Russians in Alaska, conditions improved for the coastal Alaska Natives who had survived contact. The Tlingits were never conquered and continued to wage war on the Russians into the 1850s. The Aleuts, though faced with a decreasing population in the 1840s, ultimately rebounded.

Alaska purchase

Financial difficulties in Russia, the desire to keep Alaska out of British hands, and the low profits of trade with Alaskan settlements all contributed to Russia's willingness to sell its possessions in North America.

After Russian America was sold to the U.S., all the holdings of the Russian–American Company were liquidated.

The Department of Alaska (1867–1884)

The United States flag was raised on October 18, 1867, now called Alaska Day, and the region changed from the Julian calendar to the Gregorian calendar. Therefore, for residents, Friday, October 6, 1867 was followed by Friday, October 18, 1867—two Fridays in a row because of the 12 day shift in the calendar minus one day for the date-line shift.

During the Department era, from 1867 to 1884, Alaska was variously under the jurisdiction of the U.S. Army (until 1877), the United States Department of the Treasury from 1877 to 1879, and the U.S. Navy from 1879 to 1884.

When Alaska was first purchased, most of its land remained unexplored. In 1865, Western Union laid a telegraph line across Alaska to the Bering Strait where it would connect, under water, with an Asian line.

District of Alaska (1884–1912)

In 1884, the region was organized and the name was changed from the Department of Alaska to the District of Alaska.

In 1899, gold was found in Alaska itself in Nome, and several towns subsequently began to be built, such as Fairbanks and Ruby. In 1902, the Alaska Railroad began to be built, which would connect from Seward to Fairbanks by 1914, though Alaska still does not have a railroad connecting it to the lower 48 states today. Still, an overland route was built, cutting transportation times to the contiguous states by days. The industries of copper mining, fishing, and canning began to become popular in the early 20th century, with 10 canneries in some major towns.

In 1903, a boundary dispute with Canada was finally resolved.

By the turn of the 20th century, commercial fishing was gaining a foothold in the Aleutian Islands. Packing houses salted cod and herring, and salmon canneries were opened. Another commercial occupation, whaling, continued with no regard for over-hunting. They pushed the bowhead whales to the edge of extinction for the oil in their tissue. The Aleuts soon suffered severe problems due to the depletion of fur seals and sea otters which they needed for survival. As well as requiring the flesh for food, they also used the skins to cover their boats, without which they could not hunt. The Americans also expanded into the Interior and Arctic Alaska, exploiting the furbearers, fish, and other game on which Natives depended.

20th century

Alaska Territory (1912–1959)

When Congress passed the Second Organic Act in 1912, Alaska was reorganized, and renamed the Territory of Alaska.

The Depression caused prices of fish and copper, which were vital to Alaska's economy at the time, to decline. The United Congo Improvement Association asked the president to settle 400 African-American farmers in Alaska, saying that the territory would offer full political rights, but racial prejudice and the belief that only those from northern states would make suitable colonists caused the proposal to fail.

The exploration and settlement of Alaska would not have been possible without the development of the aircraft, which allowed for the influx of settlers into the state's interior, and rapid transportation of people and supplies throughout.

World War II

During World War II, two of the outer Aleutian Islands—Attu and Kiska—were invaded and occupied by Japanese troops. They were the only part of the continental territory of the United States to be occupied by the enemy during the war. Their recovery became a matter of national pride.

On June 3, 1942, the Japanese launched an air attack on Dutch Harbor, a U.S. naval base on Unalaska Island, but were repelled by U.S. forces. A few days later, the Japanese landed on the islands of Kiska and Attu, where they overwhelmed Attu villagers. The villagers were taken to Japan, where they were interned for the remainder of the war.

Attu was regained in May 1943 after two weeks of intense fighting and 3,929 American casualties: 549 killed, 1148 injured and 1200 severe cold injuries, 614 to disease and 318 dead of miscellaneous causes, The U.S. then turned its attention to the other occupied island, Kiska. From June through August, tons of bombs were dropped on the tiny island, though the Japanese ultimately escaped via transport ships. After the war, the Native Attuans who had survived their internment were resettled to Atka by the federal government, which considered their home villages too remote to defend.

In 1942, the Alaska–Canada Military Highway was completed, in part to form an overland supply route to the Soviet Union on the other side of the Bering Strait. Running from Great Falls, Montana, to Fairbanks, the road was the first stable link between Alaska and the rest of America. The construction of military bases, such as the Adak base, contributed to the population growth of some Alaskan cities. Anchorage almost doubled in size, from 4,200 people in 1940 to 8,000 in 1945.

Statehood

By the turn of the 20th century, a movement pushing for Alaska statehood began, but in the contiguous 48 states, legislators were worried that Alaska's population was too sparse, distant, and isolated, and its economy was too unstable for it to be a worthwhile addition to the United States. World War II and the Japanese invasion highlighted Alaska's strategic importance, and the issue of statehood was taken more seriously, but it was the discovery of oil at Swanson River on the Kenai Peninsula that dispelled the image of Alaska as a weak, dependent region. President Dwight D. Eisenhower signed the Alaska Statehood Act into United States law on July 4, 1958, which paved the way for Alaska's admission into the Union on January 3, 1959. Juneau, the territorial capital, continued as state capital, and William A. Egan was sworn in as the first governor.

Alaska does not have counties unlike every other American state except Louisiana. (Louisiana has parishes). Instead, it is divided into 16 boroughs and one "unorganized borough" made up of all land not within any borough. Boroughs have organized area-wide governments, but within the unorganized borough, where there is no such government, services are provided by the state. The unorganized borough is divided into artificially-created census areas by the United States Census Bureau for statistical purposes only.

On March 27, 1964 the Good Friday earthquake struck South-central Alaska, churning the earth for four minutes with a magnitude of 9.2. The earthquake was one of the most powerful ever recorded and killed 139 people. Most of them were drowned by the tsunamis that tore apart the towns of Valdez and Chenega.

1968 – present: oil and land politics

Oil discovery, the Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act(ANCSA), and the Trans-Alaska Pipeline

The 1968 discovery of oil on the North Slope's Prudhoe Bay—which would turn out to have the most recoverable oil of any field in the United States—would change Alaska's political landscape for decades.

This discovery catapulted the issue of Native land ownership into the headlines. In the mid-1960s, Alaska Natives from many tribal groups had united in an effort to gain title to lands wrested from them by Europeans, but the government had responded slowly before the Prudhoe Bay discovery. The government finally took action when permitting for a pipeline crossing the state, necessary to get Alaskan oil to market, was stalled pending the settlement of Native land claims.

In 1971, with major petroleum dollars on the line, the Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act was signed into law by Richard Nixon. Under the Act, Natives relinquished aboriginal claims to their lands in exchange for access to 44 million acres (180,000 km²) of land and payment of $963 million. The settlement was divided among regional, urban, and village corporations, which managed their funds with varying degrees of success.

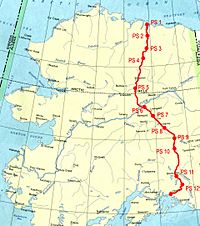

Though a pipeline from the North Slope to the nearest ice-free port, almost 800 miles (1,300 km) to the south, was the only way to get Alaska's oil to market, significant engineering challenges lay ahead. Between the North Slope and Valdez, there were active fault lines, three mountain ranges, miles of unstable, boggy ground underlain with frost, and migration paths of caribou and moose. The Trans-Alaska Pipeline was ultimately completed in 1977 at a total cost of $8 billion.

The pipeline allowed an oil bonanza to take shape.

Environmentalism, the Exxon Valdez, and ANWR

Oil production was not the only economic value of Alaska's land, however. In the second half of the 20th century, Alaska discovered tourism as an important source of revenue. Tourism became popular after World War I, when men stationed in the region returned home praising its natural splendor. The Alcan Highway, built during the war, and the Alaska Marine Highway System, completed in 1963, made the state more accessible than before. Tourism became increasingly important in Alaska, and today over 1.4 million people visit the state each year.

With tourism more vital to the economy, environmentalism also rose in importance.

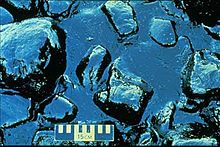

The possible environmental repercussions of oil production became clear in the Exxon Valdez oil spill of 1989. On March 24, the tanker Exxon Valdez ran aground in Prince William Sound, releasing 11 million gallons of crude oil into the water, spreading along 1,100 miles (1,800 km) of shoreline. According to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, at least 300,000 sea birds, 2,000 otters, and other marine animals died because of the spill. Exxon spent US$2 billion on cleaning up in the first year alone.

Today, the tension between preservation and development is seen in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge (ANWR) drilling controversy. The question of whether to allow drilling for oil in ANWR has been a political football for every sitting American president since Jimmy Carter.

Notable historical figures

- Clarence L. Andrews (1862–1948), civil servant in Alaska during the early 20th century, also a journalist, author, photographer and historian with a focus on Russian America.

- Alexander Baranov (1746–1819), Russian trader and governor of Alaska.

- Edward Lewis "Bob" Bartlett (1904–1968), grew up in Fairbanks, was territorial delegate to the U.S. House of Representatives 1945–1959, and United States Senator from 1959 until his death. There are a substantial number of places throughout the state named for him.

- Benny Benson (1913–1972), Alaska Native from Chignik. Designed Alaska's flag at age 13 as a resident of the Jesse Lee Home.

- Vitus Bering (1681–1741), Danish explorer for the Russians, the first European to reach Alaska.

- Charles E. Bunnell (1878–1956), territorial federal judge, first president of the University of Alaska.

- John B. "Jack" Coghill (born 1925), merchant from Nenana. Held territorial or state elected offices spanning a period of over 40 years, including Lieutenant Governor 1990–1994. One of three surviving delegates to Alaska's constitutional convention 1955–1956.

- Jimmy Doolittle (1896–1993), James Harold "Jimmy" Doolittle grew up in Nome, was a distinguished general in the United States Army Air Forces during World War II, including earning the Medal of Honor.

- Wyatt Earp (1848–1929), lived in Alaska from 1897 to 1901, built the Dexter Saloon in Nome.

- William A. Egan (1914–1984), native of Valdez. Merchant, mayor and legislator. President of Alaska's constitutional convention 1955–1956, "Alaska-Tennessee Plan" (shadow) United States Senator 1956–1958, and following proclamation of statehood, the first and fourth governor of Alaska 1959–1966 and 1970–1974.

- Carl Ben Eielson (1897–1929), pioneering aviator.

- Vic Fischer (born 1924), another surviving delegate to Alaska's constitutional convention (the third is Seaborn J. Buckalew Jr., born 1920). Retired professor and researcher at the University of Alaska Anchorage, state senator 1981–1987.

- Ernest Henry Gruening (1887–1974), veteran journalist on the east coast of the United States and bureaucrat in the FDR administration, was appointed Governor of the Territory of Alaska in 1939, and served until 1953. He was one of the new state of Alaska's first two United States Senators, serving until 1969. Chiefly known as a Senator for one of two votes again the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution.

- Jay Hammond (1922–2005), resided for the better part of 50 years in rural southwest Alaska. Mayor and legislator. Fifth Governor of Alaska 1974–1982, during the construction of the Trans-Alaska Pipeline System and the rapid changes in state government which followed, including the Permanent Fund and its dividend program. Also known for his conservationist views and a unique way with words.

- B. Frank Heintzleman (1888–1965), official with the U.S. Forest Service in Alaska, appointed territorial governor and served during the height of activity on obtaining statehood for Alaska.

- Saint Herman of Alaska (1756–1837), Russian missionary, first Eastern Orthodox saint in North America.

- Walter Hickel (1919–2010), real estate developer/industrialist. Governor 1966–1969, resigned to become U.S. Secretary of the Interior under President Nixon, elected to another term as governor 1990, served until 1994.

- Sheldon Jackson (1834–1909), an American missionary of the Presbyterian Church and educator, also instrumental in introducing reindeer to Alaska from Siberia. The educational institute he established in Sitka for Native youths became the Sheldon Jackson Museum and College (the latter now closed).

- Joseph Juneau (1836–1899), and Richard Harris (1833–1907), prospectors and founders of what is now Alaska's capital city, Juneau.

- Austin Eugene "Cap" Lathrop (1865–1950), industrialist, founder of some of Alaska's oldest radio stations and builder of currently recognized historic architecture. Produced The Chechahcos, the first movie produced in Alaska. Lathrop's feud with Gruening over statehood issues spawned the novel and film Ice Palace.

- Loren Leman (born 1950), Lieutenant Governor 2002–2006, the first Alaska Native elected to statewide office.

- Ray Mala (1906–1952), the first Native American and first Alaskan to become a film star. He starred in MGM's Eskimo/Mala the Magnificent, which was filmed entirely on location in Alaska. His son, Dr. Ted Mala, became an influential Alaska Native physician, and was also Commissioner of Health and Social Services during Hickel's second governorship.

- Eva McGown (1883–1972), Fairbanks hostess and chorister. Also the basis for a character in Ice Palace.

- John Muir (1838–1914), naturalist, explorer, and conservationist who detailed his journeys throughout Alaska. Was instrumental, along with Gifford Pinchot, in establishing the first wilderness and forest preserves in Alaska during the presidency of Theodore Roosevelt.

- William Oefelein (born 1965), Alaska's first astronaut. His first mission, STS-116. Commander Oefelein, who attended West Anchorage High School, received his commission from Aviation Officer Candidate School in 1988.

- Sarah Palin (born 1964), Alaska's youngest Governor, first female Governor and Republican Vice Presidential nominee in 2008.

- Elizabeth Peratrovich (1911–1958), an Alaska Native of Tlingit heritage who fought for passage of non-discrimination laws for Natives and is honored with "Elizabeth Peratrovich Day."

- Tex Rickard (1870–1929), like Wyatt Earp, also a major figure in the Nome Gold Rush c. 1900–1901, and better known for exploits elsewhere.

- George Sharrock (1910–2005), moved to the territory before statehood, eventually elected as the mayor of Anchorage and served during the Good Friday earthquake in March 1964. This was the most devastating earthquake to hit Alaska and it sank beach property, damaged roads and destroyed buildings all over the south central area. Sharrock, sometimes called the "earthquake mayor," led the city's rebuilding effort over six months.

- Soapy Smith (1860–1898), Jefferson Randolph Smith, "Alaska's Outlaw." The infamous confidence man and early settler, who ran the goldrush town of Skagway, Alaska, 1897–98.

- Ted Stevens (1923–2010), United States Senator from Alaska 1968–2009, the longest service of any Republican member. Was originally appointed by Hickel following Bartlett's death, and re-elected seven times before losing re-election in 2008 as he faced a corruption trial. Widely known as a Senator as an often loud and angry advocate for Alaska. Died in a plane crash near Dillingham.

- Fran Ulmer (born 1947), Lieutenant Governor 1994–2002, the first woman elected to statewide office in Alaska, later became chancellor of the University of Alaska Anchorage.

- Saint Innocent of Alaska (1797–1879), First Russian Orthodox bishop in North America.

- Joe Vogler (1913–1993), advocate of secession for Alaska, founder of the Alaskan Independence Party, multiple time unsuccessful candidate for governor.

- Noel Wien (1899–1977), pioneering aviator, founder of Wien Air Alaska, first to make a round trip between Alaska and Asia.

- Ferdinand von Wrangell (1797–1870), explorer, president of the Russian-American Company in 1840–1849.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Historia de Alaska para niños

In Spanish: Historia de Alaska para niños