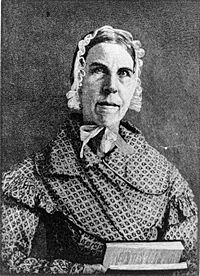

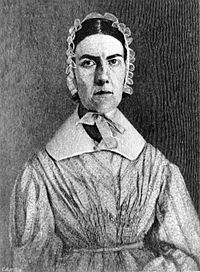

Grimké sisters facts for kids

Sarah Moore Grimké (1792–1873) and Angelina Emily Grimké (1805–1879), known as the Grimké sisters, were the first nationally-known white American female advocates of abolition of slavery and women's rights. They were speakers, writers, and educators.

They were and remained the only Southern white women in the abolition movement. As the first American-born women to make a public speaking tour, they opened the way for women to take part in public affairs. As the first female anti-slavery agents, they early saw the connection between civil rights for Negroes and civil rights for women. Sarah Grimke's pamphlet, The Equality of the Sexes and the Condition of Women, represents the first serious discussion of woman's rights by an American woman.

They grew up in a slave-owning family in South Carolina, and in their twenties, became part of Philadelphia’s substantial Quaker society. They became deeply involved with the abolitionist movement, traveling on its lecture circuit and recounting their firsthand experiences with slavery on their family's plantation. Among the first American women to act publicly in social reform movements, they were ridiculed for their abolitionist activity. They became early activists in the women's rights movement. They eventually founded a private school.

After discovering that their late brother had had three mixed-race sons, whose mother was one of his slaves, they helped the boys get education in the North. Archibald and Francis J. Grimké stayed in the North, Francis becoming a Presbyterian minister, but their younger brother John returned to the South.

Early life and education

Judge John Faucheraud Grimké, the father of the Grimké sisters, was strong advocate of slavery. A wealthy planter who held hundreds of slaves, Grimké had 14 children with his wife and had at least three children from enslaved women. (See Children of the plantation.) Three of the children died in infancy. Grimké served as chief judge of the Supreme Court of South Carolina.

Sarah was the sixth child, and Angelina was the thirteenth. Sarah said that at age five after she saw a slave being whipped, she tried to board a steamer to a place where there was no slavery. Later, in violation of the law, she taught her personal slave to read.

Sarah wanted to become a lawyer and follow in her father's footsteps. She studied the books in her father's library constantly, teaching herself geography, history, and mathematics, but her father would not allow her to learn Latin, or go to college with her brother Thomas, who was at Yale Law School. Still, her father appreciated her keen intelligence, and told her that if she had been a man, she would have been the greatest lawyer in South Carolina.

After completing her studies, Sarah begged her parents to allow her to become Angelina's godmother. She became a role model to her younger sibling, and the two sisters had a close relationship all their lives. Angelina often called Sarah "mother".

Sarah became an abolitionist in 1835.

Social activism

Sarah was twenty-six when she accompanied her father, who was in need of medical attention, to Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, where she became acquainted with the Quakers. The Quakers had liberal views on slavery and gender equality, and Sarah was fascinated with their religious sincerity and simplicity, and also their disapproval of gender inequality and slavery. Because of her father's death, Sarah had to leave Philadelphia in 1818 and return to Charleston. There her abolitionist views grew stronger, while she also influenced Angelina.

Sarah left Charleston for good in 1821, and relocated to Philadelphia, where Angelina joined her in 1829. The sisters became very involved in the Quaker community. In 1835 Angelina wrote a letter to Wm. Lloyd Garrison, editor and publisher of The Liberator, which he published without her permission. As Quakers of the time were strict on traditional manners, as well as on individuals' deference to all decisions of the congregation before taking public actions, both sisters were immediately rebuked by the Quaker community — yet sought out by the abolitionist movement. The sisters had to choose: recant and become members in good standing in the Quaker community, or actively work to oppose slavery. They chose the latter course.

Alice S. Rossi says that this choice "seemed to free both sisters for a rapidly escalating awareness of the many restrictions upon their lives. Their physical and intellectual energies were soon fully expanded, as though they and their ideas had been suddenly released after a long period of germination." Abolitionist Theodore Weld, who would later marry Angelina, trained them to be abolition speakers. Contact with like-minded individuals for the first time in their lives enlivened the sisters.

Sarah was rebuked again in 1836 by Quakers when she tried to discuss abolition in a meeting. Following the earlier example of the African-American orator Maria W. Stewart of Boston, the Grimké sisters were among the first female public speakers in the United States. They first spoke to "parlor meetings" or "sewing circles," of women only, as was considered proper. Interested men frequently sneaked into the meetings. The sisters gained attention because of their class and background in having slaves, and coming from a wealthy planter family.

As they attracted larger audiences, the Grimké sisters began to speak in front of mixed audiences (both men and women). They challenged social conventions in two ways: first, speaking for the antislavery movement at a time when it was not popular to do so; many male public speakers on this issue were criticized in the press. Secondly, their very act of public speaking was criticized, as it was not believed suitable for women. A group of ministers wrote a letter citing the Bible and reprimanding the sisters for stepping out of the "woman's proper sphere," which was characterized by silence and subordination. They came to understand that women were oppressed and, without power, women could not address or right the wrongs of society. They became ardent feminists.

Angelina Grimké wrote her first tract, Appeal to the Christian Women of the South (1836), to encourage Southern women to join the abolitionist movement for the sake of white womanhood as well as black slaves. She addressed Southern women in sisterly, reasonable tones. She began her piece by demonstrating that slavery was contrary to the United States' Declaration of Independence and to the teachings of Christ. She discussed the damage both to slaves and to society. She advocated teaching slaves to read, and freeing any slaves her readers might own. Although legal codes of slave states restricted or prohibited both of these actions, she urged her readers to ignore wrongful laws and do what was right. "Consequences, my friends, belong no more to you than they did to [the] apostles. Duty is ours and events are God's." She closed by exhorting her readers to "arise and gird yourselves for this great moral conflict."

The sisters created more controversy when Sarah published Epistle to the Clergy of the Southern States (1836) and Angelina republished her Appeal in 1837. That year they went on a lecture tour, addressing Congregationalist churches in the Northeast. In addition to denouncing slavery, the sisters denounced race prejudice. Further, they argued that (white) women had a natural bond with female black slaves. These last two ideas were extreme even for radical abolitionists. Their public speaking for the abolitionist cause continued to draw criticism, each attack making the Grimké sisters more determined. Responding to an attack by Catharine Beecher on her public speaking, Angelina wrote a series of letters to Beecher, later published with the title Letters to Catharine Beecher; staunchly defended the abolitionist cause and her right to publicly speak for that cause. By the end of the year, the sisters were being denounced from Congregationalist pulpits. The following year Sarah responded to the ministers' attacks by writing a series of letters addressed to the president of the abolitionist society which sponsored their speeches. These became known as Letters on the Equality of the Sexes, in which she defended women's right to the public platform. By 1838, thousands of people flocked to hear their Boston lecture series.

In 1839 the sisters, with Weld, published American Slavery as It Is: Testimony of a Thousand Witnesses, a collection of eyewitness testimony and advertisements from Southern newspapers.

Until 1854, Theodore was often away from home, either on the lecture circuit or in Washington, DC. After that, financial pressures forced him to take up a more lucrative profession. For a time they lived on a farm in New Jersey and operated a boarding school. Many abolitionists, including Elizabeth Cady Stanton, sent their children to the school. Eventually, it developed as a cooperative, the Raritan Bay Union. Although the sisters no longer spoke on the lecture circuit, they continued to be privately active as both abolitionists and feminists.

Neither Sarah nor Angelina initially sought to become feminists, but felt the role was unavoidable. Devoutly religious, these Quaker converts' works are predominantly religious in nature, with strong Biblical arguments. Indeed, both their abolitionist sentiments and their feminism sprang from deeply-held religious convictions. Both Sarah, who eventually emphasized feminism over abolitionism, and Angelina, who remained primarily interested in the abolitionist movement, were powerful writers. They neatly summarized the abolitionist arguments which would eventually lead to the Civil War. Sarah's work addressed many issues that are familiar to the feminist movement of the late 20th century, 150 years later.

Before the Civil War, the sisters discovered that their late brother Henry had had a relationship with Nancy Weston, an enslaved mixed-race woman, after he became a widower. They lived together and had three mixed-race sons: Archibald, Francis, and John (who was born a couple of months after their father died). The sisters arranged for the oldest two nephews to come north for education and helped support them. Francis J. Grimké became a Presbyterian minister who graduated from Lincoln University (Pennsylvania) and Princeton Theological Seminary. In December 1878, Francis married Charlotte Forten, a noted educator and author, and had one daughter, Theodora Cornelia, who died as an infant. The daughter of Archibald, Angelina Weld Grimké (named after her aunt), became a noted poet.

When Sarah was nearly 80, to test the 15th Amendment, the sisters attempted, unsuccessfully, to vote.

Legacy

"The Grimké Sisters at Work on Theodore Dwight Weld's American Slavery as It Is (1838)" is a poem by Melissa Range published in the September 30, 2019, issue of The Nation.

The book The invention of wings by Sue Monk Kidd is set during the antebellum years and is based on the life of Sarah Grimké.

Archival material

The papers of the Grimké family are in the South Carolina Historical Society, Charleston, South Carolina. The Weld–Grimké papers are William L. Clements Library, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan.