Giant squid facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Giant squid |

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | |

| Phylum: | |

| Class: | |

| Subclass: | |

| Order: | |

| Suborder: |

Oegopsina

|

| Family: |

Architeuthidae

Pfeffer, 1900

|

| Genus: |

Architeuthis

Steenstrup, 1857b

|

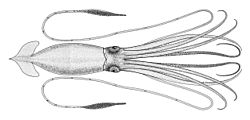

The giant squid Architeuthis is a genus of deep-ocean dwelling squid. Giant squid can grow to a tremendous size: recent estimates put the maximum size at 13 metres (43 ft) for females and 10 metres (33 ft) for males from caudal fin to the tip of the two long tentacles

There is a larger squid, known as the Colossal Squid.

Until 2005, nobody had ever seen a giant squid that was alive. Only dead giant squids had been found. On 30 September 2004, researchers from Japan took the first images of a live giant squid in its natural habitat. Several of the 556 photographs were released a year later. The same team successfully filmed a live adult giant squid for the first time on December 4, 2006.

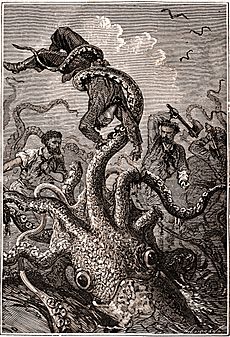

There is no agreement as to how many species there are. The Kraken is also believed to be a giant squid,

Contents

History

For many years, people would hear stories from fishermen about giant squids at sea. According to the stories, an enormous squid would wrap its arms around a whale, causing a terrible fight to start. Whalers said that sometimes, when they caught a whale, it would have scars as big as dinner plates on its body. Other times, when they cut open the stomach of some of their whales, they would find squid arms as long as 30 ft with suckers up to four inches wide. The whalers who told these stories either chopped up the squid parts to eat or use as bait, or they threw them back out to sea before scientists were ever able to examine them. However, in 1861, a French ship was able to bring back parts of a giant squid so scientists could study them.

Then, in the late 18th century, several giant squids washed up on shore, proving that giant squids really exist. After that, many giant squids were found washed ashore or dead at sea. Scientists grew very interested in these mysterious creatures, but few ever saw them alive. Scientists think they spend most of their time in deep, cold ocean.

In December 2005, the Melbourne Aquarium in Australia got the intact body of a giant squid, preserved in a giant block of ice. It had been caught by fishermen off the coast of New Zealand's South Island that year.

The number of known giant squid specimens was close to 600 in 2004, and new ones are reported each year.

Description

Like all squid, a giant squid has a mantle (torso), eight arms, and two longer tentacles (the longest known tentacles of any cephalopod). The arms and tentacles account for much of the squid's great length, making it much lighter than its chief predator, the sperm whale. Scientifically documented specimens have masses of hundreds, rather than thousands, of kilograms.

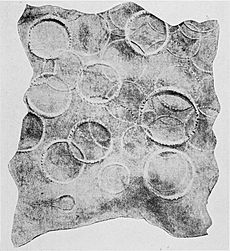

The inside surfaces of the arms and tentacles are lined with hundreds of subspherical suction cups, 2 to 5 cm (0.79 to 1.97 in) in diameter, each mounted on a stalk. The circumference of these suckers is lined with sharp, finely serrated rings of chitin. The perforation of these teeth and the suction of the cups serve to attach the squid to its prey. It is common to find circular scars from the suckers on or close to the head of sperm whales that have attacked giant squid. Each arm and tentacle is divided into three regions – carpus ("wrist"), manus ("hand") and dactylus ("finger"). The carpus has a dense cluster of cups, in six or seven irregular, transverse rows. The manus is broader, close to the end of the arm, and has enlarged suckers in two medial rows. The dactylus is the tip. The bases of all the arms and tentacles are arranged in a circle surrounding the animal's single, parrot-like beak, as in other cephalopods.

Giant squid have small fins at the rear of their mantles used for locomotion. Like other cephalopods, they are propelled by jet – by pulling water into the mantle cavity, and pushing it through the siphon, in gentle, rhythmic pulses. They can also move quickly by expanding the cavity to fill it with water, then contracting muscles to jet water through the siphon. Giant squid breathe using two large gills inside the mantle cavity. The circulatory system is closed, which is a distinct characteristic of cephalopods. Like other squid, they contain dark ink used to deter predators.

The giant squid has a sophisticated nervous system and complex brain, attracting great interest from scientists. It also has the largest eyes of any living creature except perhaps the colossal squid – up to at least 27 cm (11 in) in diameter, with a 9 cm (3.5 in) pupil (only the extinct ichthyosaurs are known to have had larger eyes). Large eyes can better detect light (including bioluminescent light), which is scarce in deep water. The giant squid probably cannot see colour, but it can probably discern small differences in tone, which is important in the low-light conditions of the deep ocean.

Giant squid and some other large squid species maintain neutral buoyancy in seawater through an ammonium chloride solution which is found throughout their bodies and is lighter than seawater. This differs from the method of flotation used by most fish, which involves a gas-filled swim bladder. The solution tastes somewhat like salmiakki and makes giant squid unattractive for general human consumption.

Like all cephalopods, giant squid use organs called statocysts to sense their orientation and motion in water. The age of a giant squid can be determined by "growth rings" in the statocyst's statolith, similar to determining the age of a tree by counting its rings. Much of what is known about giant squid age is based on estimates of the growth rings and from undigested beaks found in the stomachs of sperm whales.

Size

The giant squid is the second-largest mollusc and the second largest of all extant invertebrates. It is only exceeded by the colossal squid, Mesonychoteuthis hamiltoni, which may have a mantle nearly twice as long. Several extinct cephalopods, such as the Cretaceous vampyromorphid Tusoteuthis, the Cretaceous coleoid Yezoteuthis, and the Ordovician nautiloid Cameroceras may have grown even larger.

Giant squid size, particularly total length, has often been exaggerated. Reports of specimens reaching and even exceeding 20 m (66 ft) are widespread, but no animals approaching this size have been scientifically documented. According to giant squid expert Steve O'Shea, such lengths were likely achieved by greatly stretching the two tentacles like elastic bands.

Based on the examination of 130 specimens and of beaks found inside sperm whales, giant squids' mantles are not known to exceed 2.25 m (7.4 ft). Including the head and arms, but excluding the tentacles, the length very rarely exceeds 5 m (16 ft). Maximum total length, when measured relaxed post mortem, is estimated at 13 m (43 ft) for females and 10 m (33 ft) for males from the posterior fins to the tip of the two long tentacles.

Giant squid exhibit sexual dimorphism. Maximum weight is estimated at 275 kg (606 lb) for females and 150 kg (330 lb) for males.

Ecology

Feeding

Recent studies have shown giant squid feed on deep-sea fish and other squid species. They catch prey using the two tentacles, gripping it with serrated sucker rings on the ends. Then they bring it toward the powerful beak, and shred it with the radula (tongue with small, file-like teeth) before it reaches the esophagus. They are believed to be solitary hunters, as only individual giant squid have been caught in fishing nets. Although the majority of giant squid caught by trawl in New Zealand waters have been associated with the local hoki (Macruronus novaezelandiae) fishery, hoki do not feature in the squid's diet. This suggests giant squid and hoki prey on the same animals.

Predators

The only known predators of adult giant squid are sperm whales, but pilot whales may also feed on them. Juveniles are preyed on by deep-sea sharks and other fish. Because sperm whales are skilled at locating giant squid, scientists have tried to observe them to study the squid.

Range and habitat

Giant squid are widespread, occurring in all of the world's oceans. They are usually found near continental and island slopes from the North Atlantic Ocean, especially Newfoundland, Norway, the northern British Isles, Spain and the oceanic islands of the Azores and Madeira, to the South Atlantic around southern Africa, the North Pacific around Japan, and the southwestern Pacific around New Zealand and Australia. Specimens are rare in tropical and polar latitudes.

Images for kids

-

Architeuthis sanctipauli was described in 1877 based on a specimen found washed ashore in Île Saint-Paul three years earlier.

See also

In Spanish: Calamares gigantes para niños

In Spanish: Calamares gigantes para niños