Garry Kasparov facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Garry KasparovГарри Каспаров |

|

|---|---|

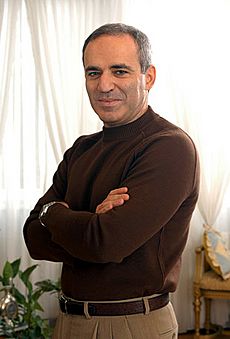

Kasparov in 2015

|

|

| Full name | Garry Kimovich Kasparov |

| Country |

|

| Born | 13 April 1963 Baku, Azerbaijan SSR, Soviet Union |

| Title | Grandmaster (1980) |

| World Champion |

|

| FIDE rating | 2812 (April 2025) |

| Peak rating | 2851 (July 1999) |

| Peak ranking | No. 1 (January 1984) |

Garry Kimovich Kasparov (born Garik Kimovich Weinstein on 13 April 1963) is a Russian chess grandmaster, former World Chess Champion (1985–2000), political activist and writer. His peak FIDE chess rating of 2851, achieved in 1999, was the highest recorded until being surpassed by Magnus Carlsen in 2013. From 1984 until his retirement from regular competitive chess in 2005, Kasparov was ranked world no. 1 for a record 255 months overall. Kasparov also holds records for the most consecutive professional tournament victories (15) and Chess Oscars (11).

Kasparov became the youngest-ever undisputed world champion in 1985 at age 22 by defeating then-champion Anatoly Karpov, a record he held until 2024, when Gukesh Dommaraju won the title at age 18. Kasparov defended the title against Karpov three times, in 1986, 1987 and 1990. Kasparov held the official FIDE world title until 1993, when a dispute with FIDE led him to set up a rival organisation, the Professional Chess Association. In 1997, he became the first world champion to lose a match to a computer under standard time controls when he was defeated by the IBM supercomputer Deep Blue in a highly publicised match. He continued to hold the "Classical" world title until his defeat by Vladimir Kramnik in 2000. Despite losing the PCA title, he continued winning tournaments and was the world's highest-rated player at the time of his official retirement. Kasparov coached Carlsen in 2009–10, during which time Carlsen rose to world no. 1. Kasparov stood unsuccessfully for FIDE president in 2013–2014.

Since retiring from chess, Kasparov has devoted his time to writing and politics. His book series My Great Predecessors, first published in 2003, details the history and games of the world champion chess players who preceded him. He formed the United Civil Front movement and was a member of The Other Russia, a coalition opposing the administration and policies of Vladimir Putin. In 2008, he announced an intention to run as a candidate in that year's Russian presidential race, but after encountering logistical problems in his campaign, for which he blamed "official obstruction", he withdrew. Following the Russian mass protests that began in 2011, he announced in June 2013 that he had left Russia for the immediate future out of fear of persecution. Following his flight from Russia, he lived in New York City with his family. In 2014, he obtained Croatian citizenship and has maintained a residence in Podstrana near Split.

Kasparov was chairman of the Human Rights Foundation from 2011 to 2024. In 2017, he founded the Renew Democracy Initiative (RDI), an American political organisation promoting and defending liberal democracy in the U.S. and abroad. He serves as chairman of the group. Kasparov is also a security ambassador for the software company Avast.

Contents

Early life

Kasparov was born Garik Kimovich Weinstein (Russian: Гарик Кимович Вайнштейн, romanized: Garik Kimovich Vainshtein) in Baku, Azerbaijan SSR (now Azerbaijan), Soviet Union. His father, Kim Moiseyevich Weinstein, was Jewish and his mother, Klara Shagenovna Kasparova, was Armenian. Both of his mother's parents were Armenians from Karabak. Kasparov has described himself as a "self-appointed Christian", although "very indifferent" and identifying as Russian: "[A]lthough I'm half-Armenian, half-Jewish, I consider myself Russian because Russian is my native tongue, and I grew up with Russian culture." Kasparov and his family had to flee anti-Armenian pogroms in Baku in January 1990 that were coordinated by local leaders with Soviet acquiescence.

According to Kasparov himself, he was named after United States President Harry Truman, "whom my father admired for taking a strong stand against communism. It was a rare name in Russia, until Harry Potter came along."

Introduction to chess

Kasparov began the serious study of chess after he came across a problem set up by his parents and proposed a solution. When he was seven years old, his father died of leukaemia. At the age of twelve, Kasparov, upon the request of his mother Klara and with the consent of the family, adopted Klara's surname Kasparov, which was done to avoid possible anti-Semitic tensions common in the USSR at the time.

From age seven, Kasparov attended the Young Pioneer Palace in Baku and, at ten, began training at Mikhail Botvinnik's chess school under coach Vladimir Makogonov. Makogonov helped develop Kasparov's positional skills and taught him to play the Caro–Kann Defence and the Tartakower System of the Queen's Gambit Declined. Kasparov won the Soviet Junior Championship in Tbilisi in 1976, scoring 7/9 points, at age thirteen. He repeated the feat the following year, winning with a score of 8.5/9. He was being coached by Alexander Shakarov during this time.

In 1978, Kasparov participated in the Sokolsky Memorial tournament in Minsk. He had received a special invitation to enter the tournament but took first place and became a chess master. Kasparov has stressed that this event was a turning point in his life and that it convinced him to choose chess as his career: "I will remember the Sokolsky Memorial as long as I live", he wrote. He has also said that after the victory, he thought he had a very good shot at the world championship.

Chess career

Rising up the ranks

He first qualified for the USSR Chess Championship at age 15 in 1978, the youngest-ever player at that level. He won the 64-player Swiss system tournament at Daugavpils on a tie-break over Igor V. Ivanov to capture the sole qualifying place.

Kasparov rose quickly through the FIDE world rankings. Due to an oversight by the USSR Chess Federation, which believed that a grandmaster tournament in Banja Luka, Yugoslavia, was for juniors, he participated in that event in 1979 while still unrated. He was a replacement for the Soviet defector Viktor Korchnoi, who was originally invited but withdrew due to the threat of a boycott from the Soviets. Kasparov won this high-class tournament, emerging with a provisional rating of 2595, enough to catapult him to the top group of chess players (at the time, number 15 in the world). The next year, 1980, he won the World Junior Chess Championship in Dortmund, West Germany. Later that year, he made his debut as the second reserve for the Soviet Union at the Chess Olympiad at Valletta, Malta, and became a Grandmaster.

As a teenager, Kasparov shared the USSR Chess Championship in 1981 with Lev Psakhis (12.5/17), although Psakhis won their game. His first win in a superclass-level international tournament was scored at Bugojno, Yugoslavia, in 1982. He earned a place in the 1982 Moscow Interzonal tournament, which he won, to qualify for the Candidates Tournament. At age 19, he was the youngest Candidate since Bobby Fischer, who was 15 when he qualified in 1958. At this stage, he was already the No. 2-rated player in the world, trailing only world champion Karpov on the January 1983 list.

Kasparov's first (quarter-final) Candidates match was against Alexander Beliavsky, whom he defeated 6–3 (four wins, one loss). Politics threatened Kasparov's semi-final against Korchnoi, which was scheduled to be played in Pasadena, California. Korchnoi had defected from the Soviet Union in 1976 and was at that time the strongest active non-Soviet player. The Soviet authorities would not allow Kasparov to travel to the United States, meaning that Korchnoi could have had a walkover. This decision was met with disapproval by the chess world, and Korchnoi agreed to the match to being played in London instead, along with the previously scheduled match between Vasily Smyslov and Zoltán Ribli. The Kasparov-Korchnoi match was put together on short notice by Raymond Keene. Kasparov lost the first game but won the match 7–4 (four wins, one loss).

In January 1984, Kasparov became the No. 1 ranked player in the world, with a FIDE rating of 2710. He became the youngest-ever world No. 1, a record that lasted 12 years until being broken by Kramnik in January 1996. That same year, he won the Candidates' final 8½–4½ (four wins, no losses) against former world champion Smyslov at Vilnius, thus qualifying to play Karpov for the world championship.

1984 world championship

The World Chess Championship 1984 match between Kasparov and Karpov had many ups and downs and a controversial finish. Karpov started in very good form, and after nine games Kasparov was down 4–0 in a "first to six wins" match. Fellow players predicted he would be whitewashed 6–0 within 18 games.

In an unexpected turn of events, there followed a series of 17 successive draws, some relatively short, others drawn in unsettled positions. Kasparov lost game 27 (5–0), then fought back with another series of draws until game 32, earning his first-ever win against the world champion and bringing the score to 5–1. Another 14 successive draws followed, through game 46; the previous record length for a world title match had been 34 games (José Raúl Capablanca vs. Alexander Alekhine in 1927).

Kasparov won games 47 and 48 to bring the score to 5–3 in Karpov's favour. Then the match was ended without result by FIDE President Florencio Campomanes, and a new match was announced to start a few months later. The termination was controversial, as both players stated that they preferred the match to continue. Announcing his decision, Campomanes cited the health of the players, which had been strained by the length of the match. According to grandmasters Boris Gulko and Korchnoi, and historians Vladimir Popow and Yuri Felshtinsky in their The KGB Plays Chess book, Campomanes had been a KGB agent and was tasked with preventing Karpov's defeat at all costs. The match was terminated while Karpov was still ahead to avoid the impression that the decision had been made for his benefit.

The match became the first, and so far only, world championship match to be abandoned without a result. Kasparov's relations with Campomanes and FIDE became strained, and matters came to a head in 1993 with Kasparov's complete break-away from FIDE.

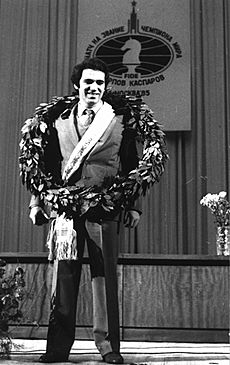

World champion

The second Karpov–Kasparov match in 1985 was organised in Moscow as the best of 24 games, where the first player to win 12½ points would claim the title. The scores from the terminated match would not carry over; however, in the event of a 12–12 draw, the title would remain with Karpov. On 9 November 1985, Kasparov secured the world crown by a score of 13–11. Karpov, with White, needed to win the 24th game to retain the title but Kasparov won it with the Sicilian Defence. He was 22 years old at the time, making him the youngest-ever world champion, a record held by Mikhail Tal for over 20 years. Kasparov's win with Black in the 16th game has been recognised as one of the all-time chess masterpieces, including being voted the best game played during the first 64 issues of the magazine Chess Informant.

As part of the arrangements following the aborted 1984 match, Karpov had been granted (in the event of his defeat) a right to rematch. Another match took place in 1986, hosted jointly in London and Leningrad, with each city hosting 12 games. At one point in the match, Kasparov opened a three-point lead and looked well on his way to a decisive victory. But Karpov fought back by winning three consecutive games to level the score late in the match. At this point, Kasparov dismissed one of his seconds, grandmaster Evgeny Vladimirov, accusing him of selling his opening preparation to the Karpov team (as described in Kasparov's autobiography Unlimited Challenge, chapter Stab in the Back). Kasparov scored one more win and kept his title by a score of 12½–11½.

A fourth match for the world title took place in 1987 in Seville, as Karpov had qualified through the Candidates' Matches to become the official challenger once again. This match was also very close, with neither player holding more than a one-point lead at any time. With one game left, Kasparov was down a point and needed a win to draw the match and retain his title. A long, tense game ensued, in which Karpov blundered away a pawn just before the first time control. Kasparov then won a long ending to retain the title on a 12–12 scoreline.

Kasparov and Karpov met for a fifth time, on this occasion in New York City and Lyon in 1990, with each city hosting 12 games. Again, the result was a close one, with Kasparov winning by a margin of 12½–11½. In their five world championship matches, Kasparov had 21 wins, 19 losses and 104 draws in 144 games.

Break with and ejection from FIDE

In November 1986, Kasparov had created the Grandmasters Association (GMA) to represent professional players and give them more say in FIDE's activities. Kasparov assumed a leadership role. GMA's major achievement was in organising a series of six World Cup tournaments for the world's top players. This caused an uneasy relationship to develop between Kasparov and FIDE. The previous month, Kasparov had made his feelings clear to fellow grandmaster Keene: "Campomanes must go. It is war to the death with him as far as I am concerned. I will do everything I can to remove him”.

This stand-off lasted until 1993, by which time a new challenger had qualified through the Candidates cycle: Nigel Short, a British grandmaster who had defeated Karpov in a qualifying match and then Jan Timman in the finals held in early 1993. After a confusing and compressed bidding process produced lower financial estimates than expected, the world champion and his challenger both rejected FIDE's bid for an August match in Manchester and decided to play outside FIDE's jurisdiction. Their match took place under the auspices of the Professional Chess Association (PCA), an organisation established by Kasparov and Short. At this point, a fracture occurred in the lineage of the FIDE World Championship. In an interview in 2007, Kasparov called the break with FIDE in 1993 the worst mistake of his career, as it hurt the game in the long run.

Kasparov and Short were ejected from FIDE and played their well-sponsored match in London in September 1993. Kasparov won convincingly by a score of 12½–7½. The match considerably raised the profile of chess in the UK, with a substantial level of coverage on Channel 4. Meanwhile, FIDE organised its world championship match between Timman (the defeated Candidates finalist) and former world champion Karpov (a defeated Candidates semi-finalist), which Karpov won.

FIDE removed Kasparov and Short from its rating list. Subsequently, the PCA created a rating list of its own, which featured all the world's top players regardless of their relation to FIDE. There were now two world champions: PCA champion Kasparov and FIDE champion Karpov. The title remained split for 13 years.

Kasparov defended his PCA title in a 1995 match against Viswanathan Anand at the World Trade Center in New York City. Kasparov won the match by four wins to one, with thirteen draws.

Kasparov tried to organise another world championship match under a different organisation, the World Chess Association (WCA), with Linares organiser Luis Rentero. Alexei Shirov and Kramnik played a candidates match to decide the challenger, which Shirov won in an upset. But when Rentero admitted that the funds required and promised had never materialised, the WCA collapsed. Yet another body stepped in, BrainGames.com, headed by Raymond Keene. After a match with Shirov could not be agreed by BrainGames.com and talks with Anand collapsed, a match was instead arranged against Kramnik.

During this period, Kasparov was approached by Oakham School in the United Kingdom, at the time the only school in the country with a full-time chess coach, and developed an interest in the use of chess in education. In 1997, Kasparov supported a scholarship programme at the school. Kasparov also won the Marca Leyenda trophy that year.

In 1999, he played a well-known game against Topalov wherein he won after a rook sacrifice and king hunt.

Losing the title and aftermath

The Kasparov-Kramnik match took place in London during the latter half of 2000. Kramnik had been a student of Kasparov's at the famous Botvinnik/Kasparov chess school in Russia and had served on Kasparov's team for the 1995 match with Anand.

The better-prepared Kramnik won game 2 against Kasparov's Grünfeld Defence and achieved winning positions in games 4 and 6, although Kasparov managed a draw in both games. Kasparov made a critical error in game 10 with the Nimzo-Indian Defence, which Kramnik exploited to win in 25 moves. As White, Kasparov could not crack the passive but solid Berlin Defence in the Ruy Lopez, and Kramnik managed to draw all his games as Black. Kramnik won the match 8½–6½.

Kasparov won a series of major tournaments and remained the PCA top-rated player in the world, ahead of both Kramnik and the FIDE World Champion. In 2001, he refused an invitation to the 2002 Dortmund Candidates Tournament for the Classical title, claiming his results had earned him a rematch with Kramnik.

Kasparov and Karpov played a four-game match with rapid time controls over two days in December 2002 in New York City. Kasparov suffered a surprise loss (1.5 – 2.5).

Because of Kasparov's continuing strong results and status as FIDE world No. 1, he was included in the so-called "Prague Agreement", masterminded by Yasser Seirawan and intended to reunite the two world championships. Kasparov was to play a match against the FIDE World Champion Ponomariov in September 2003. But this match was called off after Ponomariov refused to sign his contract for it without reservation. In its place, there were plans for a match against Rustam Kasimdzhanov, winner of the FIDE World Chess Championship 2004, to be held in January 2005 in the United Arab Emirates. These also fell through owing to a lack of funding. Plans to hold the match in Turkey instead came too late. Kasparov announced in January 2005 that he was tired of waiting for FIDE to arrange a match and had decided to stop all efforts to become undisputed world champion once more.

Retirement from regular competitive chess

After winning the prestigious Linares tournament for the ninth time, Kasparov announced on 10 March 2005 that he would retire from regular competitive chess. He cited as the reason a lack of personal goals in the chess world. When winning the Russian championship in 2004, he commented that it had been the last major title he had never won outright. He also expressed frustration at the failure to reunify the world championship.

Kasparov said he might play in some rapid chess events for fun, but he intended to spend more time on his books, including the My Great Predecessors series, and work on the links between decision-making in chess and other areas of life. He also stated that he would continue to involve himself in Russian politics, which he viewed as "headed down the wrong path."

Post-retirement chess

On 22 August 2006, in his first public chess games since his retirement, Kasparov played in the Lichthof Chess Champions Tournament, a blitz event played at the time control of five minutes per side and three-second increments per move. Kasparov tied for first with Karpov, scoring 4½/6.

Kasparov and Karpov played a 12-game match from 21 to 24 September 2009, in Valencia, Spain. It consisted of four rapid (or semi rapid) games, in which Kasparov won 3–1, and eight blitz games, in which Kasparov won 6–2, winning the match with a final result of 9–3. The event took place exactly 25 years after the two players' unfinished encounter at World Chess Championship 1984.

Kasparov coached Carlsen for approximately one year, beginning in February 2009. The collaboration remained secret until September 2009. Under Kasparov's tutelage, in October 2009 Carlsen became the youngest ever to achieve a FIDE rating higher than 2800, and he rose from world number four to world number one. While the pair initially planned to work together throughout 2010, in March of that year it was announced that Carlsen had split from Kasparov and would no longer be using him as a trainer. According to an interview with the German magazine Der Spiegel, Carlsen indicated that he would remain in contact and that he would continue to attend training sessions with Kasparov; however, no further training sessions were held, and the cooperation fizzled out over the course of the spring. In 2011, Carlsen said: "Thanks to [Kasparov] I began to understand a whole class of positions better. ... Kasparov gave me a great deal of practical help." In 2012, when asked what he learnt from working with Kasparov, Carlsen answered: "Complex positions. That was the most important thing."

In May 2010, Kasparov played and won 30 games simultaneously against players at Tel Aviv University in Israel. In the same month, it was revealed that he had aided Anand in his preparation for the World Chess Championship 2010 against challenger Veselin Topalov. Anand won the match 6½–5½ to retain the title.

Kasparov began training the U.S. grandmaster Hikaru Nakamura in January 2011. The first of several training sessions was held in New York just before Nakamura participated in the Tata Steel Chess tournament in Wijk aan Zee, the Netherlands. In December 2011, it was announced that their cooperation had come to an end.

Kasparov played two blitz exhibition matches in the autumn of 2011. The first was in September against French grandmaster Maxime Vachier-Lagrave, in Clichy (France), which Kasparov won 1½–½. The second was a longer match consisting of eight blitz games played on 9 October, against English grandmaster Short. Kasparov won again by a score of 4½–3½. A little after that, in October 2011, Kasparov played and defeated fourteen opponents in a simultaneous exhibition that took place in Bratislava.

On 25 and 26 April 2015, Kasparov played a mini-match against Short. The match consisted of two rapid games and eight blitz games and was contested over the course of two days. Commentators GM Maurice Ashley and Alejandro Ramírez remarked how Kasparov was an 'initiative hog' throughout the match, consistently not allowing Short to gain any foothold in the games. Kasparov won the match decisively (8½–1½), winning all five games on the second day. These victories were characterised by aggressive pawn moves breaking up Short's position, thereby allowing Kasparov's pieces to achieve positional superiority.

Kasparov played and won all nineteen games of a simultaneous exhibition in Pula, Croatia on 19 August 2015. At the Chess Club and Scholastic Center of Saint Louis on 28 and 29 April 2016, Kasparov played a 6-round exhibition blitz round-robin tournament with Fabiano Caruana, Wesley So and Nakamura in an event called the Ultimate Blitz Challenge. He finished the tournament third with 9.5/18, behind Nakamura (11/18) and So (10/18). At the post-tournament interview, Kasparov announced that he would donate his winnings from playing the next top-level blitz exhibition match to assist funding of the American Olympic Team.

On 2 June 2016, Kasparov played against fifteen chess players in a simultaneous exhibition in the Kaiser-Friedrich-Halle of Mönchengladbach. He won all games.

Candidate for FIDE presidency

On 7 October 2013, Kasparov announced his candidacy for World Chess Federation president during a reception in Tallinn, Estonia, where the 84th FIDE Congress took place. He was supported by reigning world champion and FIDE #1 ranked player Carlsen. At the FIDE General Assembly in August 2014, Kasparov lost the presidential election to the incumbent Kirsan Ilyumzhinov, with a vote of 110–61.

A few days before the election took place, the New York Times Magazine had published a report on the viciously fought campaign. Included was information about a leaked contract between Kasparov and former FIDE Secretary General Ignatius Leong from Singapore, in which the Kasparov campaign reportedly "offered to pay Leong US$500,000 and to pay $250,000 a year for four years to the ASEAN Chess Academy, an organisation Leong helped create to teach the game, specifying that Leong would be responsible for delivering 11 votes from his region [...]". In September 2015, the FIDE Ethics Commission found Kasparov and Leong guilty of violating its Code of Ethics and later suspended them for two years from all FIDE functions and meetings.

Return from chess retirement

Kasparov came out of retirement to participate in the inaugural St. Louis Rapid and Blitz tournament from 14 to 19 August 2017, scoring 3.5/9 in the rapid and 9/18 in the blitz, representing Croatia. He finished eighth in a strong field of ten, including Nakamura, Caruana, former world champion Anand and the eventual winner, Levon Aronian. Kasparov promised that any tournament money he earned would go towards charities to promote chess in Africa.

In 2020, he participated in 9LX, a Chess 960 tournament, and finished eighth of a field of ten players. His game against Carlsen, who tied for first place, was drawn.

He launched Kasparovchess, a subscription-based online chess community featuring documentaries, lessons, puzzles, podcasts, articles, interviews and playing zones, in 2021.

Kasparov played in the blitz section of the Grand Chess Tour 2021 event in Zagreb, Croatia. He performed poorly, however, scoring 0.5/9 on the first day and 2/9 on the second day, getting his only win against Jorden Van Foreest. He also participated in 9LX 2, finishing fifth in a field of ten players, with a score of 5/9.

Olympiads and major team events

Kasparov played in a total of eight Chess Olympiads. He represented the Soviet Union four times and Russia four times, following the break-up of the Soviet Union in 1991. In his 1980 Olympiad debut, he became, at age 17, the youngest player to represent the Soviet Union or Russia at that level, a record which was broken by Kramnik in 1992. In 82 games, he scored (+50−3=29), for 78.7%, and won a total of nineteen medals, including team gold medals all eight times he competed.

For the 1994 Moscow Olympiad, he had a significant organisational role in helping to put together the event on short notice, after Thessaloniki cancelled its offer to host only a few weeks before the scheduled dates. Kasparov's detailed Olympiad record follows:

- Valletta 1980, USSR 2nd reserve, 9½/12 (+8−1=3), team gold, board bronze;

- Lucerne 1982, USSR 2nd board, 8½/11 (+6−0=5), team gold, board bronze;

- Dubai 1986, USSR 1st board, 8½/11 (+7−1=3), team gold, board gold, performance gold;

- Thessaloniki 1988, USSR 1st board, 8½/10 (+7−0=3), team gold, board gold, performance gold;

- Manila 1992, Russia board 1, 8½/10 (+7−0=3), team gold, board gold, performance silver;

- Moscow 1994, Russia board 1, 6½/10 (+4−1=5), team gold;

- Yerevan 1996, Russia board 1, 7/9 (+5−0=4), team gold, board silver, performance gold;

- Bled 2002, Russia board 1, 7½/9 (+6−0=3), team gold, performance gold.

Kasparov made his international debut for the USSR at age 16 in the 1980 European Team Championship and played for Russia in the 1992 edition of that championship. He won a total of five medals. His detailed record in this event follows:

- Skara 1980, USSR 2nd reserve, 5½/6 (+5−0=1), team gold, board gold;

- Debrecen 1992, Russia board 1, 6/8 (+4−0=4), team gold, board gold, performance silver.

Kasparov also represented the USSR once at the Youth Olympiad in Austria (1981). He scored 9/10 (+8–0=2) on the top board and his team lifted the title.

Assessment and legacy

Kasparov received a Chess Oscar eleven times as the best chess player of the year, in 1982–1983, 1985–1988, 1995–1996, 1999, and 2001–2002. Between 1981 and 1991, he won or tied for first place in every tournament he entered. In 1999, Kasparov reached an Elo rating of 2851 points, a record that stood for over thirteen years: on 10 December 2012, Carlsen achieved an unofficial rating of 2861 points, with which he topped the next release of the rating in January 2013. With the exception of the PCA period and sharing first place with Kramnik in 1997, Kasparov led the rating list from 1985 to 2006 – a total of 255 months. On 1 January 2006, Kasparov ranked first with a coefficient of 2812. However, he was excluded from the FIDE rating list of 1 April 2006 because he had not participated in tournaments for the previous twelve months.

The rivalry between Kasparov and Karpov (often referred to as the "two Ks") is one of the greatest in the history of chess. In six years they played five matches comprising 144 games. For a long time there was personal enmity between Karpov and Kasparov. The conflict between the two men also had a political connotation. Karpov was considered a representative of the Soviet nomenklatura, while Kasparov was young and popular, positioned himself as a "child of change", willingly gave candid interviews and (especially in the West) had an aura of a rebel, although he was never a dissident. Kasparov's 1985 victory coincided with the start of perestroika in the Soviet Union.

Carlsen said of Kasparov: "I've never seen someone with such a feel for dynamics in complex positions." Kramnik has opined that Kasparov's "capacity for study is second to none", adding "There is nothing in chess he has been unable to deal with."

In 2007, the international consulting company Synectics published a rating of 100 living geniuses in science, politics, art and entrepreneurship, in which Kasparov ranked 25th.

Less known about Kasparov is his emphasis on physical fitness, including taking a month off each year to work out strenuously.

Playing style

Kramnik called Kasparov a chess player with virtually no weaknesses. His games are characterised by a dynamic style of play with a focus on tactics, depth of strategy, subtle calculation and original opening ideas. Kasparov was known for his extensive opening preparation and aggressive play in it. Sergey Shipov considered Kasparov's moral and volitional qualities (impulsiveness and psychological instability) and excessive reliance on options, which can lead to overwork and mistakes, as amongst his few shortcomings.

Kasparov's attacking style of play has been compared by many to Alekhine, his chess idol since childhood. Kasparov has described his style as being influenced chiefly by Alekhine, Tal and Fischer. Other influences on Kasparov were his early coaches. At a young age, he met with experienced teachers Alexander Nikitin and Alexander Shakarov. Shakarov collected and systematised materials, and then became the keeper of Kasparov's "information bank". A revolutionary step at that time was the involvement of computer programs in analysing games, and it was Kasparov and his team who took the first steps in this direction. In 1973, Kasparov entered the Botvinnik school and immediately attracted attention. Botvinnik commented on the young schoolboy: "Garry's speed and memory capacity are amazing. He counts deep variations and finds unexpected moves. The power of combinational vision makes him similar to Alekhine himself".

Contributions to opening theory

Kasparov has made many contributions to opening theory. In the 1990s, he systematically developed new variants with computer programs. He also "reanimated" the Scotch Game in top-level competitions. Kasparov successfully used this opening, which was considered outdated, in the 1990 match against Karpov and in matches with Short and Anand. One of the offshoots of the Sicilian in the Szén Variation is called the Kasparov Gambit. Kasparov used this variation in the 12th and 16th games of the match with Karpov in 1985; in the second of these games, he scored a victory.

Another well-known case of winning an important game thanks to a novelty in the opening is Kasparov's 10th game of the 1995 match against Anand. On the 14th move, in a well-known position of the open variation of the Spanish Game (Ruy Lopez), Kasparov discovered a new idea with a rook sacrifice, which brought a decisive attack.

Kasparov has also co-authored several books on opening theory.

Chess rating

Kasparov holds the record for the longest time as the No. 1 rated player in the world—from 1984 to 2005 (Kramnik shared the No. 1 ranking with him once, in the January 1996 FIDE rating list). He headed the PCA rating list during the split from FIDE. At the time of his retirement, he was still ranked No. 1 in the world, with a rating of 2812. His rating has fallen inactive since the January 2006 rating list.

In January 1990, Kasparov achieved the (then) highest FIDE rating ever, passing 2800 and breaking Fischer's old record of 2785. By the July 1999 and January 2000 FIDE rating lists, Kasparov had reached a 2851 Elo rating, at that time the highest rating ever achieved. He held that record until Carlsen attained a new record high rating of 2861 in January 2013.

Other achievements

Kasparov holds the record for most consecutive professional tournament victories, placing first or equal first in fifteen individual tournaments from 1981 to 1990. The streak was broken by Vasyl Ivanchuk at Linares 1991, where Kasparov placed second, half a point behind him after losing their individual game. The details of this record winning streak follow:

- Frunze 1981, USSR Championship, 12½/17, tie for 1st;

- Bugojno 1982, 9½/13, 1st;

- Moscow 1982, Interzonal, 10/13, 1st;

- Nikšić 1983, 11/14, 1st;

- Brussels OHRA 1986, 7½/10, 1st;

- Brussels SWIFT 1987, 8½/11, tie for 1st;

- Amsterdam Optiebeurs 1988, 9/12, 1st;

- Belfort (World Cup) 1988, 11½/15, 1st;

- Moscow 1988, USSR Championship, 11½/17, tie for 1st;

- Reykjavík (World Cup) 1988, 11/17, 1st;

- Barcelona (World Cup) 1989, 11/16, tie for 1st;

- Skellefteå (World Cup) 1989, 9½/15, tie for 1st;

- Tilburg 1989, 12/14, 1st;

- Belgrade (Investbank) 1989, 9½/11, 1st;

- Linares 1990, 8/11, 1st.

Kasparov went nine years winning every super-tournament he played, in addition to contesting his series of five consecutive matches with Karpov. His only failure in this time period in either tournament or match play was the 1984 world title match against Karpov.

In the late 1990s, Kasparov went on another long streak of ten consecutive super-tournament wins.

- Wijk aan Zee Hoogovens 1999, 10/13, 1st;

- Linares 1999, 10½/14, 1st;

- Sarajevo 1999, 7/9, 1st;

- Wijk aan Zee Corus 2000, 9½/13, 1st;

- Linares 2000, 6/10, tie for 1st;

- Sarajevo 2000, 8½/11, 1st;

- Wijk aan Zee Corus 2001, 9/13, 1st;

- Linares 2001, 7.5/10, 1st;

- Astana 2001, 7/10, 1st;

- Linares 2002, 8/12, 1st.

In these tournament victories, Kasparov had a score of 53 wins, 61 draws and 1 loss in 115 games, his only defeat coming against Ivan Sokolov in Wijk aan Zee 1999.

Notable games

- Anatoly Karpov vs Garry Kasparov, World Chess Championship 1985, Game 16, Sicilian Defence, Taimanov variation (B44), 0-1. An example of him at his very best, Kasparov takes advantage of Karpov's setup in the opening, offering a pawn sacrifice before dominating all three of White's major pieces with an "octopus knight" on d3.

- Garry Kasparov vs Veselin Topalov, Hoogovens Tournament Group A, Wijk aan Zee 1999, Round 4, Pirc Defence (B07), 1-0. In what is widely regarded as his masterpiece, Kasparov unleashes multiple brilliancies as he hunts down Black's king from one side of the board to another, ending in a precise combination.

Chess and computers

Acorn Computers acted as one of the sponsors for Kasparov's Candidates semi-final match against Korchnoi in 1983. This was Kasparov's first introduction to computers. Kasparov was awarded a BBC Micro, which he took back with him to Baku, making it perhaps one of the first Western-made microcomputers to reach the Soviet Union at that time.

Computer chess magazine editor Frederic Friedel consulted with Kasparov in 1985 on how a chess database program would be useful preparation for competition. Friedel founded Chessbase two years later, and he gave a copy of the program to Kasparov, who started using it in his preparation. That same year, Kasparov played against thirty-two chess computers in Hamburg, winning all games. Several commercially available Kasparov computers were made in the 1980s, the Saitek Kasparov Turbo King models. On 22 October 1989, Kasparov defeated the chess computer Deep Thought in both games of a two-game match. In December 1992, Kasparov played thirty-seven blitz games against Fritz 2 in Cologne, winning 24, drawing 4 and losing 9.

Kasparov cooperated in producing video material for the computer game Kasparov's Gambit released by Electronic Arts in November 1993. In April 1994, Intel acted as a sponsor for the first Professional Chess Association Grand Prix event in Moscow, played at a time control of twenty-five minutes per game. In May, Chessbase's Fritz 3 running on an Intel Pentium PC defeated Kasparov in their first game in the Intel Express blitz tournament in Munich, but Kasparov managed to tie it for first and won the play-off (+3=2). The next day, Kasparov lost to Fritz 3 again in a game on ZDF TV. In August, Kasparov was knocked out of the London Intel Grand Prix by Richard Lang's ChessGenius 2 program in the first round. In 1995, during Kasparov's world title match with Anand, he unveiled an opening novelty that had been checked with a chess engine, an approach that would become increasingly common in subsequent years.

Kasparov played in a pair of six-game chess matches with IBM supercomputer Deep Blue. The first match took place in Philadelphia in February 1996 and was won by Kasparov (4–2). The second was played in New York City in May 1997 and won by Deep Blue (3½–2½). The 1997 match was the first defeat of a reigning world champion by a computer under tournament conditions. The match was even after five games but Kasparov lost quickly in Game 6. Kasparov said that he was "not well prepared" to face Deep Blue in 1997. He said that based on his "objective strengths" his play was stronger than that of Deep Blue. Kasparov claimed that several factors weighed against him in this match. In particular, he was denied access to Deep Blue's recent games, in contrast to the computer's team, which could study hundreds of Kasparov's.

After the loss, Kasparov said that he sometimes saw deep intelligence and creativity in the machine's moves, suggesting that during the second game chess players had intervened in contravention of the rules. IBM denied that it had cheated, stating the only human intervention occurred between games. The rules provided for the developers to modify the program between games, an opportunity they said they used to shore up weaknesses in the computer's play revealed during the course of the match. Kasparov requested printouts of the machine's log files but IBM refused, although the company later published them on the Internet. Much later, it was suggested that the behaviour Kasparov noted had resulted from a glitch in the computer program. Plans for further engagement between Kasparov and IBM, including a rematch, did not come to fruition, due to the accusations of cheating.

Kasparov versus the World was a game that took place in 1999. Kasparov conducted the white moves while more than 50,000 people from all over the globe played against him. The game was a huge mixture of tactical and strategical ideas, with Kasparov saying: "It is the greatest game in the history of chess. The sheer number of ideas, the complexity, and the contribution it has made to chess make it the most important game ever played." After 62 moves, Kasparov won the game.

In January 2003, he engaged in a six-game classical time control match, with a $1 million prize fund, against Deep Junior. It was billed as the FIDE "Man vs. Machine" world championship. The engine evaluated three million positions per second. After one win each and three draws, it was all up to the final game. After reaching a decent position, Kasparov offered a draw, which was accepted by the Deep Junior team. Asked why he had offered the draw, Kasparov said he feared making a blunder. Deep Junior was the first machine to beat Kasparov with Black and at a standard time control.

In June 2003, Mindscape released the computer game Kasparov Chessmate, with Kasparov himself listed as a co-designer. In November 2003, he engaged in a four-game match against the computer program X3D Fritz, using a virtual board, 3D glasses and a speech recognition system. After two draws and one win apiece, the X3D Man–Machine match ended in a draw. Kasparov received $175,000 and took home a golden trophy. He continued to regret the blunder in the second game that cost him a crucial point. He felt that he had outplayed the machine overall and performed well: "I only made one mistake but unfortunately that one mistake lost the game."

In 2021, Kasparov promoted a series of 32 NFTs that detailed important moments in his career. The top four sold for more than $11,000.

Books and other writings

Early writings

Kasparov has written books on chess. He published an autobiography when still in his early 20s. Originally titled Child of Change, it was later published as Unlimited Challenge. This book was updated several times after he became world champion. Its content is mainly literary, with a small chess component of key unannotated games. He published an annotated games collection in 1983, Fighting Chess: My Games and Career, which has been updated in further editions. He also wrote a book annotating the games from his World Chess Championship 1985 victory, World Chess Championship Match: Moscow, 1985.

He has annotated his own games extensively for the Yugoslav Chess Informant series. In 1982, he co-authored Batsford Chess Openings with British grandmaster Keene. That book sold well and was updated in a second edition in 1989. He also co-authored two opening books with his trainer Alexander Nikitin in the 1980s for British publisher Batsford – on the Classical Variation of the Caro–Kann Defence and on the Scheveningen Variation of the Sicilian Defence. Kasparov also contributed extensively to the five-volume openings series Encyclopedia of Chess Openings from Chess Informant, for which Kasparov also wrote personal columns called Garry's Choice.

In 2000, Kasparov co-authored Kasparov Against the World: The Story of the Greatest Online Challenge with grandmaster Daniel King. The 202-page book analyses the 1999 Kasparov versus the World game, and holds the record for the longest analysis devoted to a single chess game.

My Great Predecessors series

In 2003, the first volume of his five-volume work Garry Kasparov on My Great Predecessors was published. This volume deals with world champions Wilhelm Steinitz, Emanuel Lasker, Capablanca and Alekhine, and some of their strong contemporaries. It won the British Chess Federation's Book of the Year award in 2003. Volume two, covering Max Euwe, Botvinnik, Smyslov and Tal, appeared later in 2003. Volume three, featuring Tigran Petrosian and Boris Spassky, was published in early 2004. In December 2004, Kasparov released volume four, which covers Samuel Reshevsky, Miguel Najdorf and Bent Larsen (none of whom was world champion), but focuses on Fischer. The fifth volume, devoted to the chess careers of world champion Karpov and challenger Korchnoi, was published in March 2006.

Modern Chess series

His Revolution in the 70s (published in March 2007) covers "the openings revolution of the 1970s–1980s" and was the first work in a new venture, "Modern Chess Series", which recounted his matches with Karpov and selected games. Revolution in the 70s is about the development of opening theory witnessed in that decade. Systems like the novel "Hedgehog" opening plan of passively developing the pieces no further than the first three ranks were examined in great detail. Kasparov also analysed some of the most notable games played in that period. In a section at the end of the book, top opening theoreticians provided their opinion on progress made in opening theory in the 1980s.

Garry Kasparov on Garry Kasparov series

From 2011 to 2014, Kasparov published a three-volume series of his games, spanning his career in three eras until he stopped playing full-time in 2005.

Winter Is Coming

In October 2015, Kasparov published a book titled Winter Is Coming: Why Vladimir Putin and the Enemies of the Free World Must Be Stopped. The title is a reference to the HBO television series Game of Thrones. In the book, Kasparov writes about the need for an organisation composed solely of democratic countries to replace the United Nations. In an interview, he called the United Nations a "catwalk for dictators".

Historical revision

Kasparov believes that the conventional history of civilisation is incorrect. Specifically, he contends that the history of ancient civilisations is based on misdating of events and achievements that occurred in the medieval period. He has cited several aspects of ancient history that, he argues, are likely to be anachronisms.

Kasparov has written in support of the pseudohistorical New Chronology (Fomenko), although with some reservations. In 2001, he expressed a desire to devote his time to promoting the New Chronology after his chess career. "New Chronology is a great area for investing my intellect ... My analytical abilities are well placed to figure out what was right and what was wrong." "When I stop playing chess, it may well be that I concentrate on promoting these ideas... I believe they can improve our lives." Later, Kasparov renounced his support of Fomenko theories but reaffirmed his belief that mainstream historical knowledge is inconsistent.

Other post-retirement writing

Kasparov wrote How Life Imitates Chess, an examination of the parallels between decision-making in chess and in the business world, in 2007. In 2008, Kasparov published a sympathetic obituary for Fischer: "I am often asked if I ever met or played Bobby Fischer. The answer is no, I never had that opportunity. But even though he saw me as a member of the evil chess establishment that he felt had robbed and cheated him, I am sorry I never had a chance to thank him personally for what he did for our sport."

Kasparov is the chief advisor for the book publisher Everyman Chess. He works closely with Mig Greengard and his comments can often be found on Greengard's blog. Kasparov collaborated with Max Levchin and Peter Thiel on The Blueprint, a book calling for a revival of world innovation, planned for release in March 2013 but cancelled after the authors disagreed on its contents. In an editorial comment on Google's AlphaZero chess-playing system, Kasparov argued that chess has become the model for reasoning in the same way that the fruit fly Drosophila melanogaster became a model organism for geneticists: "I was pleased to see that AlphaZero had a dynamic, open style like my own," he wrote in late 2018.

Kasparov served as a consultant for the 2020 Netflix miniseries The Queen's Gambit and gave an interview to Slate on his contributions. That same year, Kasparov collaborated with Matt Calkins, founder and CEO of Appian, on Hyperautomation, a book about low-code development and the future of business automation. Kasparov wrote the foreword where he discusses his experiences with human–machine relationships. The New York Times published an essay by Kasparov titled "Garry Kasparov: What We Believe About Reality" in 2021. The essay is part of a series called The Big Ideas: What Do We Believe. This work was later published in a compendium titled Question Everything: A Stone Reader.

Personal life

Kasparov has lived in New York City since 2013.

He has been married three times: to Masha, with whom he had a daughter, Polina, before divorcing; to Yulia, with whom he had a son, Vadim, before their 2005 divorce; and to Daria (Dasha), with whom he has two children, daughter Aida born in 2006 and son Nickolas born in 2015. Kasparov's wife manages his business activities worldwide through Kasparov International Management Inc.

See also

In Spanish: Garri Kaspárov para niños

In Spanish: Garri Kaspárov para niños

- Game Over: Kasparov and the Machine, documentary film.

- Kasparov Chess, Internet chess club.

- List of chess games between Kasparov and Kramnik

- Committee 2008

- Putinism

- Advanced chess