Ernst Nolte facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

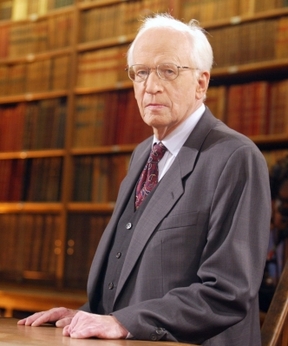

Ernst Nolte

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Born | 11 January 1923 |

| Died | 18 August 2016 (aged 93) Berlin, Germany

|

| Nationality | German |

| Education | PhD in Philosophy (1952) |

| Alma mater | University of Münster University of Berlin University of Freiburg University of Cologne |

| Occupation | Philosopher, historian |

| Employer | University of Marburg (1965–1973) Free University of Berlin (since 1973, Emeritus since 1991) |

| Known for | Articulating a theory of generic fascism as “resistance to transcendence”, and for his involvement in the Historikerstreit debate |

| Spouse(s) | Annedore Mortier |

| Children | Georg Nolte |

| Awards | Hanns Martin Schleyer Prize (1985) Konrad Adenauer Prize (2000) Gerhard Löwenthal Honor Award (2011) |

Ernst Nolte (11 January 1923 – 18 August 2016) was a German historian and philosopher. Nolte's major interest was the comparative studies of fascism and communism (cf. Comparison of Nazism and Stalinism). Originally trained in philosophy, he was professor emeritus of modern history at the Free University of Berlin, where he taught from 1973 until his 1991 retirement. He was previously a professor at the University of Marburg from 1965 to 1973. He was best known for his seminal work Fascism in Its Epoch, which received widespread acclaim when it was published in 1963. Nolte was a prominent conservative academic from the early 1960s and was involved in many controversies related to the interpretation of the history of fascism and communism, including the Historikerstreit in the late 1980s. In later years, Nolte focused on Islamism and "Islamic fascism".

Nolte received several awards, including the Hanns Martin Schleyer Prize and the Konrad Adenauer Prize. He was the father of the legal scholar and judge of the International Court of Justice Georg Nolte.

Contents

Early life

Nolte was born in Witten, Westphalia, Germany to a Roman Catholic family. Nolte's parents were Heinrich Nolte, a school rector, and Anna (née Bruns) Nolte. According to Nolte in a 28 March 2003 interview with a French newspaper Eurozine, his first encounter with communism occurred when he was 7 years old in 1930, when he read in a doctor's office a German translation of a Soviet children's book attacking the Catholic Church, which angered him.

In 1941, Nolte was excused from military service because of a deformed hand, and he studied Philosophy, Philology and Greek at the Universities of Münster, Berlin, and Freiburg. At Freiburg, Nolte was a student of Martin Heidegger, whom he acknowledges as a major influence. From 1944 onwards, Nolte was a close friend of the Heidegger family, and when in 1945 the professor feared arrest by the French, Nolte provided him with food and clothing for an attempted escape. Eugen Fink was another professor who influenced Nolte. After 1945 when Nolte received his BA in philosophy at Freiburg, he worked as a Gymnasium (high school) teacher. In 1952, he received a PhD in philosophy at Freiburg for his thesis Selbstentfremdung und Dialektik im deutschen Idealismus und bei Marx (Self Alienation and the Dialectic in German Idealism and Marx). Subsequently, Nolte began studies in Zeitgeschichte (contemporary history). He published his Habilitationsschrift awarded at the University of Cologne, Der Faschismus in seiner Epoche, as a book in 1963. Between 1965 and 1973, Nolte worked as a professor at the University of Marburg, and from 1973 to 1991 at the Free University of Berlin.

Nolte married Annedore Mortier and they had a son, Georg Nolte, now a professor of international law at Humboldt University of Berlin.

Fascism in Its Epoch

Nolte came to notice with his 1963 book Der Faschismus in seiner Epoche (Fascism in Its Epoch; translated into English in 1965 as The Three Faces of Fascism), in which he argued that fascism arose as a form of resistance to and a reaction against modernity. Nolte's basic hypothesis and methodology were deeply rooted in the German "philosophy of history" tradition, a form of intellectual history which seeks to discover the "metapolitical dimension" of history. The "metapolitical dimension" is considered to be the history of grand ideas functioning as profound spiritual powers, which infuse all levels of society with their force. In Nolte's opinion, only those with training in philosophy can discover the "metapolitical dimension", and those who use normal historical methods miss this dimension of time. Using the methods of phenomenology, Nolte subjected German Nazism, Italian Fascism, and the French Action Française movements to a comparative analysis. Nolte's conclusion was that fascism was the great anti-movement: it was anti-liberal, anti-communist, anti-capitalist, and anti-bourgeois. In Nolte's view, fascism was the rejection of everything the modern world had to offer and was an essentially negative phenomenon. In a Hegelian dialectic, Nolte argued that the Action Française was the thesis, Italian Fascism was the antithesis, and German National Socialism the synthesis of the two earlier fascist movements.

Nolte argued that fascism functioned at three levels, namely in the world of politics as a form of opposition to Marxism, at the sociological level in opposition to bourgeois values, and in the "metapolitical" world as "resistance to transcendence" ("transcendence" in German can be translated as the "spirit of modernity"). Nolte defined the relationship between fascism and Marxism as such:

Fascism is anti-Marxism which seeks to destroy the enemy by the evolvement of a radically opposed and yet related ideology and by the use of almost identical and yet typically modified methods, always, however within the unyielding framework of national self-assertion and autonomy.

Nolte defined "transcendence" as a "metapolitical" force comprising two types of change. The first type, "practical transcendence", manifesting in material progress, technological change, political equality, and social advancement, comprises the process by which humanity liberates itself from traditional, hierarchical societies in favor of societies where all men and women are equal. The second type is "theoretical transcendence", the striving to go beyond what exists in the world towards a new future, eliminating traditional fetters imposed on the human mind by poverty, backwardness, ignorance, and class. Nolte himself defined "theoretical transcendence" as such:

Theoretical transcendence may be taken to mean the reaching out of the mind beyond what exists and what can exist toward an absolute whole; in a broader sense this may be applied to all that goes beyond, that releases man from the confines of the everyday world, and which, as an ‘awareness of the horizon’, makes it possible for him to experience the world as a whole.

Nolte cited the flight of Yuri Gagarin in 1961 as an example of “practical transcendence”, of how humanity was pressing forward in its technological development and rapidly acquiring powers traditionally thought to be only the province of the gods. Drawing upon the work of Max Weber, Friedrich Nietzsche, and Karl Marx, Nolte argued that the progress of both types of "transcendence" generates fear as the older world is swept aside by a new world, and that these fears led to fascism. Nolte wrote that:

The most central of Maurras's ideas have been seen to penetrate to this level. By ‘monotheism’ and ‘anti-nature’ he did not imply a political process: he related these terms to the tradition of Western philosophy and religion, and left no doubt that for him they were not only adjuncts of Rousseau's notion of liberty, but also of the Christian Gospels and Parmenides' concept of being. It is equally obvious that he regarded the unity of world economics, technology, science and emancipation merely as another and more recent form of ‘anti-nature’. It was not difficult to find a place for Hitler ideas as a cruder and more recent expression of this schema. Maurras' and Hitler's real enemy was seen to be ‘freedom towards the infinite’ which, intrinsic in the individual and a reality in evolution, threatens to destroy the familiar and beloved. From all this it begins to be apparent what is meant by ‘transcendence’.

In regard to the Holocaust, Nolte contended that because Adolf Hitler identified Jews with modernity, the basic thrust of Nazi policies towards Jews had always aimed at genocide. Nolte believed that, for Hitler, Jews represented "the historical process itself". Nolte argues that Hitler was "logically consistent" in seeking genocide of the Jews because Hitler detested modernity and identified Jews with the things that he most hated in the world.

The Three Faces of Fascism has been much praised as a seminal contribution to the creation of a theory of generic fascism based on a history of ideas, as opposed to the previous class-based analyses (especially the "Rage of the Lower Middle Class" thesis) that had characterized both Marxist and liberal interpretations of fascism. The German historian Jen-Werner Müller wrote that Nolte "almost single-handedly" brought down the totalitarianism paradigm in the 1960s and replaced it with the fascism paradigm. British historian Roger Griffin has written that although written in arcane and obscure language, Nolte's theory of fascism as a "form of resistance to transcendence" marked an important step in the understanding of fascism, and helped to spur scholars into new avenues of research on fascism.

Criticism from the left, for example by Sir Ian Kershaw, centered on Nolte's focus on ideas as opposed to social and economic conditions as a motivating force for fascism, and that Nolte depended too much on fascist writings to support his thesis. Kershaw described Nolte's theory of fascism as "resistance to transcendence" as "mystical and mystifying". The American historian Fritz Stern wrote that The Three Faces of Fascism was an "uneven book" that was "weak" on Action Française, "strong" on Fascism and "masterly" on National Socialism.

Later in the 1970s, Nolte was to reject aspects of the theory of generic fascism that he had championed in The Three Faces of Fascism and instead moved closer to embracing totalitarian theory as a way of explaining both Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union. In Nolte's opinion, Nazi Germany was a "mirror image" of the Soviet Union and, with the exception of the "technical detail" of mass gassing, everything the Nazis did in Germany had already been done by the communists in Russia.

Methodology

All of Nolte's historical work has been heavily influenced by German traditions of philosophy. In particular, Nolte seeks to find the essences of the "metapolitical phenomenon" of history, to discover the grand ideas which motivated all of history. As such, Nolte's work has been oriented towards the general as opposed to the specific attributes of a particular period of time. In his 1974 book Deutschland und der kalte Krieg (Germany and the Cold War), Nolte examined the partition of Germany after 1945, not by looking at the specific history of the Cold War and Germany, but rather by examining other divided states throughout history, treating the German partition as the supreme culmination of the "metapolitical" idea of partition caused by rival ideologies. In Nolte's view, the division of Germany made that nation the world's central battlefield between Soviet communism and American democracy, both of which were rival streams of the "transcendence" that had vanquished Nazi Germany, the ultimate enemy of "transcendence". Nolte called the Cold War

the ideological and political conflict for the future structure of a united world, carried on for an indefinite period since 1917 (indeed anticipated as early as 1776) by several militant universalisms, each of which possesses at least one major state.

Nolte ended Deutschland und der kalte Krieg with a call for Germans to escape their fate as the world's foremost battleground for the rival ideologies of American democracy and Soviet communism by returning to the values of the German Empire. Likewise, Nolte called for the end of what he regarded as the unfair stigma attached to German nationalism because of National Socialism, and demanded that historians recognize that every country in the world had at some point in its history had "its own Hitler era, with its monstrosities and sacrifices".

In 1978, the American historian Charles S. Maier described Nolte's approach in Deutschland und der kalte Krieg as:

This approach threatens to degenerate into the excessive valuation of abstraction as a surrogate for real transactions that Heine satirized and Marx dissected. How should we cope with a study that begins its discussion of the Cold War with Herodotus and the Greeks versus the Persians? ... Instead Nolte indulges in a potted history of Cold War events as they engulfed Asia and the Middle East as well as Europe, up through the Sino-Soviet dispute, the Vietnam War and SALT. The rationale is evidently that Germany can be interpreted only in the light of the world conflict, but the result verges on a centrifugal, coffee-table narrative.

Nolte has little regard for specific historical context in his treatment of the history of ideas, opting to seek what Carl Schmitt labeled the abstract "final" or "ultimate" ends of ideas, which for Nolte are the most extreme conclusions which can be drawn from an idea, representing the ultima terminus of the "metapolitical". For Nolte, ideas have a force of their own, and once a new idea has been introduced into the world, except for the total destruction of society, it cannot be ignored any more than the discovery of how to make fire or the invention of nuclear weapons can be ignored. In his 1974 book Deutschland und der kalte Krieg (Germany and the Cold War), Nolte wrote there was "a worldwide reproach that the United States was after all putting into practice in Vietnam, nothing less than its basically crueler version of Auschwitz".

The books Der Faschismus in seiner Epoche, Deutschland und der kalte Krieg, and Marxismus und industrielle Revolution (Marxism and the Industrial Revolution) formed a trilogy in which Nolte seeks to explain what he considered to be the most important developments of the 20th century.

The Historikerstreit

Nolte's thesis

Nolte is best known for his role in launching the Historikerstreit ("Historians' Dispute") of 1986 and 1987. On 6 June 1986 Nolte published a feuilleton opinion piece entitled "Vergangenheit, die nicht vergehen will: Eine Rede, die geschrieben, aber nicht mehr gehalten werden konnte" ("The Past That Will Not Pass: A Speech That Could Be Written but Not Delivered") in the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung. His feuilleton was a distillation of ideas he had first introduced in lectures delivered in 1976 and in 1980. Earlier in 1986, Nolte had planned to deliver a speech before the Frankfurt Römerberg Conversations (an annual gathering of intellectuals), but he had claimed that the organizers of the event withdrew their invitation. In response, an editor and co-publisher of the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, Joachim Fest, allowed Nolte to have his speech printed as a feuilleton in his newspaper. One of Nolte's leading critics, British historian Richard J. Evans, claims that the organizers of the Römerberg Conversations did not withdraw their invitation, and that Nolte had just refused to attend.

Nolte began his feuilleton by remarking that it was necessary in his opinion to draw a "line under the German past". Nolte argued that the memory of the Nazi era was "a bugaboo, as a past that in the process of establishing itself in the present or that is suspended above the present like an executioner's sword". Nolte complained that excessive present-day interest in the Nazi period had the effect of drawing "attention away from the pressing questions of the present—for example, the question of "unborn life" or the presence of genocide yesterday in Vietnam and today in Afghanistan".

Nolte sees his work as the beginning of a much-needed revisionist treatment to end the "negative myth" of Nazi Germany that dominates contemporary perceptions. Nolte took the view that the principal problem of German history was this "negative myth" of Nazi Germany, which cast the Nazi era as the ne plus ultra of evil.

Nolte contends that the great decisive event of the 20th century was the Russian Revolution of 1917, which plunged all of Europe into a long-simmering civil war that lasted until 1945. To Nolte, fascism, communism's twin, arose as a desperate response by the threatened middle classes of Europe to what Nolte has often called the "Bolshevik peril". He suggests that if one wishes to understand the Holocaust, one should begin with the Industrial Revolution in Britain, and then understand the rule of the Khmer Rouge in Cambodia.

In his 1987 book Der europäische Bürgerkrieg, 1917–1945, Nolte argued in the interwar period, Germany was Europe's best hope for progress. Nolte wrote that "if Europe was to succeed in establishing itself as a world power on an equal footing [with the United States and the Soviet Union], then Germany had to be the core of the new 'United States'". Nolte claimed if Germany had to continue to abide by Part V of the Treaty of Versailles, which had disarmed Germany, then Germany would have been destroyed by aggression from her neighbors sometime later in the 1930s, and with Germany's destruction, there would have been no hope for a "United States of Europe". The British historian Richard J. Evans accused Nolte of engaging in a geopolitical fantasy.

Habermas' attack

The philosopher Jürgen Habermas in an article in the Die Zeit of 11 July 1986 strongly criticized Nolte, along with Andreas Hillgruber and Michael Stürmer, for engaging in what Habermas called “apologetic” history writing in regards to the Nazi era, and for seeking to “close Germany’s opening to the West” that in Habermas's view has existed since 1945.

In particular, Habermas took Nolte to task for suggesting a moral equivalence between the Holocaust and the Khmer Rouge genocide. In Habermas's opinion, since Cambodia was a backward, Third World agrarian state and Germany a modern, industrial state, there was no comparison between the two genocides.

Later work

In his 1991 book Geschichtsdenken im 20. Jahrhundert (Historical Thinking in the 20th Century), Nolte asserted that the 20th century had produced three “extraordinary states”, namely Germany, the Soviet Union, and Israel. He claimed that all three were “abnormal once”, but whereas the Soviet Union and Germany were now “normal” states, Israel was still “abnormal” and, in Nolte's view, in danger of becoming a fascist state that might commit genocide against the Palestinians.

Between 1995 and 1997, Nolte debated with the French historian François Furet in an exchange of letters on the relationship between fascism and communism. The debate had started with a footnote in Furet's book, Le Passé d'une illusion (The Passing of an Illusion), in which Furet acknowledged Nolte's merit of comparatively studying communism and Nazism, an almost-forbidden practice in Continental Europe. Both ideologies typify in a radical way the contradictions of liberalism. They follow a chronological sequence: Lenin predates Mussolini, who, in turn, precedes Hitler. Furet noted that Nolte's theses went against the established notions of culpability and apprehension to criticize the idea of anti-fascism common in the West. This prompted an epistolary exchange between the two of them in which Furet argued that both ideologies were totalitarian twins that shared the same origins, but Nolte maintained his views of a kausaler Nexus (causal nexus) between fascism and communism to which the former had been a response. After Furet's death, their correspondence was published as a book in France in 1998, Fascisme et Communisme: échange épistolaire avec l'historien allemand Ernst Nolte prolongeant la Historikerstreit (Fascism and Communism: Epistolary Exchanges with the German Historian Ernst Nolte Extending the Historikerstreit). It was translated into English as Fascism and Communism in 2001. While pronouncing Stalin guilty of great crimes, Furet contended that although the histories of fascism and communism were essential to European history, there were singular events associated with each movement which differentiated them. He did not feel there was a precise parallel, as Nolte suggested, between the Holocaust and dekulakization.

Nolte often contributed Feuilleton (opinion pieces) to German newspapers such as Die Welt and the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung. He was often described as one of the "most brooding, German thinkers about history".

On 4 June 2000, Nolte was awarded the Konrad Adenauer Prize. The award attracted considerable public debate and was presented to Nolte by Horst Möller, the Director of the Institut für Zeitgeschichte (Institute for Contemporary History), who praised Nolte’s scholarship but tried to steer clear of Nolte’s more controversial claims. In his acceptance speech, Nolte commented, "We should leave behind the view that the opposite of National Socialist goals is always good and right," while suggesting that excessive "Jewish" support for Communism furnished the Nazis with "rational reasons" for their anti-Semitism.

In August 2000, Nolte wrote a favorable review in the Die Woche newspaper of Norman Finkelstein’s book The Holocaust Industry, claiming Finkelstein’s book buttressed his claim that the memory of the Holocaust had been used by Jewish groups for their own reasons. Nolte’s positive review of The Holocaust Industry may have been related to Finkelstein’s endorsement in his book of Nolte’s demand, first made during the Historikerstreit, for the “normalization” of the German past

In a 2004 book review of Richard Overy's monograph The Dictators, the American historian Anne Applebaum argued that it was a valid intellectual exercise to compare the German and the Soviet dictatorships, but she complained that Nolte's arguments had needlessly discredited the comparative approach. In response, Paul Gottfried in 2005 defended Nolte from Applelbaum's charge of attempting to justify the Holocaust by contending that Nolte had merely argued that the Nazis had made a link in their own minds between Jews and communists and that the Holocaust was their attempt to eliminate the most likely supporters of communism. In a June 2006 interview with the newspaper Die Welt, Nolte echoed theories that he had first expressed in The Three Faces of Fascism by identifying Islamic fundamentalism as a "third variant", after communism and National Socialism, of "the resistance to transcendence". He expressed regret that he would not have enough time for a full study of Islamic fascism In the same interview, Nolte said that he could not forgive Augstein for calling Hillgruber a "constitutional Nazi" during the Historikerstreit and claimed that Wehler had helped to hound Hillgruber to his death in 1989. Nolte ended the interview by calling himself a philosopher, not a historian, and argued that the hostile reactions that he often encountered from historians were caused by his status as a philosopher writing history.

In his 2005 book The Russian Roots of Nazism: White Émigrés and The Making of National Socialism, the American historian Michael Kellogg argued that there were two extremes of thinking about the origins of National Socialism, with Nolte arguing for a "causal nexus" between communism in Russia and Nazism in Germany, but the other extreme was represented by the American historian Daniel Goldhagen, whose theories debate a unique German culture of "eliminationist" anti-Semitism. Kellogg argued that his book represented an attempt at adopting a middle position between Nolte's and Goldhagen's positions but that he leaned closer to Nolte's by contending that anti-Bolshevik and anti-Semitic Russian émigrés played an underappreciated key role in the 1920s in the development of Nazi ideology, their influence on Nazi thinking about Judeo-Bolshevism being especially notable.

In his 2006 book Europe at War 1939–1945: No Simple Victory, the British historian Norman Davies lends Nolte's theories support:

Ten years later, in The European Civil War (1987), the German historian Ernst Nolte (b. 1923) brought ideology into the equation. The First World War had spawned the Bolshevik Revolution, he maintained, and fascism should be seen as a "counter-revolution" against communism. More pointedly, since fascism followed communism chronologically, he argued that some of the Nazis' political techniques and practices had been copied from those of the Soviet Union. Needless to say, such propositions were thought anathema by leftists who believe that fascism was an original and unparalleled evil.

Davies concluded that revelations made after the fall of communism in Eastern Europe about Soviet crimes had discredited Nolte's critics.

Awards

- Hanns Martin Schleyer Prize (1985)

- Konrad Adenauer Prize (2000)

- Gerhard Löwenthal Honor Award (2011)

Works

- "Marx und Nietzsche im Sozialismus des jungen Mussolini" pp. 249–335 from Historische Zeitschrift, Volume 191, Issue #2, October 1960.

- "Die Action Française 1899–1944" pp. 124–165 from Vierteljahrshefte für Zeitgeschichte, Volume 9, Issue 2, April 1961.

- "Eine frühe Quelle zu Hitlers Antisemitismus" pp. 584–606 from Historische Zeitschrift, Volume 192, Issue #3, June 1961.

- “Zur Phänomenologie des Faschismus” pp. 373–407 from Vierteljahrshefte für Zeitgeschichte, Volume 10, Issue #4, October 1962.

- Der Faschismus in seiner Epoche: die Action française der italienische Faschismus, der Nationalsozialismus, München : R. Piper, 1963, translated into English as The Three Faces of Fascism; Action Francaise, Italian Fascism, National Socialism, London, Weidenfeld and Nicolson 1965.

- Review of Action Français Royalism and Reaction in Twentieth-Century France by Eugen Weber pp. 694–701 from Historische Zeitschrift, Volume 199, Issue # 3, December 1964.

- Review of Le origini del socialismo italiano by Richard Hostetter pp. 701–704 from Historische Zeitschrift, Volume 199, Issue #3, December 1964.

- Review of Albori socialisti nel Risorgimento by Carlo Francovich pp. 181–182 from Historische Zeitschrift, Volume 200, Issue # 1, February 1965.

- “Grundprobleme der Italienischen Geschichte nach der Einigung” pp. 332–346 from Historische Zeitschrift, Volume 200, Issue #2, April 1965.

- “Zur Konzeption der Nationalgeschichte heute” pp. 603–621 from Historische Zeitschrift, Volume 202, Issue #3, June 1966.

- "Zeitgenössische Theorien über den Faschismus" pp. 247–268 from Vierteljahrshefte für Zeitgeschichte, Volume 15, Issue #3, July 1967.

- Der Faschismus: von Mussolini zu Hitler. Texte, Bilder und Dokumente, Munich: Desch, 1968.

- Die Krise des liberalen Systems und die faschistischen Bewegungen, Munich: R. Piper, 1968.

- Sinn und Widersinn der Demokratisierung in der Universität, Rombach Verlag: Freiburg, 1968.

- Les Mouvements fascistes, l'Europe de 1919 a 1945, Paris : Calmann-Levy, 1969.

- "Big Business and German Politics: A Comment" pp. 71–78 from The American Historical Review, Volume 75, Issue#1, October 1969.

- “Zeitgeschichtsforschung und Zeitgeschichte” pp. 1–11 from Vierteljahrshefte für Zeitgeschichte, Volume 18. Issue #1, January 1970.

- “The Relationship Between "Bourgeois" And "Marxist" Historiography” pp. 57–73 from History & Theory, Volume 14, Issue 1, 1975.

- “Review: Zeitgeschichte als Theorie. Eine Erwiderung” pp. 375–386 from Historische Zeitschrift, Volume 222, Issue #2, April 1976.

- Was ist bürgerlich? und andere Artikel, Abhandlungen, Auseinandersetzungen, Stuttgart: Klett-Cotta, 1979.

- "What Fascism Is Not: Thoughts on the Deflation of a Concept: Comment" pp. 389–394 from The American Historical Review, Volume 84, Issue #2, April 1979.

- “Deutscher Scheinkonstitutionalismus?” pp. 529–550 from Historische Zeitschrift, Volume 288, Issue #3, June 1979.

- "Marxismus und Nationalsozialismus" pp. 389–417 from Vierteljahrshefte für Zeitgeschichte, Volume 31, Issue # 3 July 1983.

- Review of Revolution und Weltbürgerkrieg. Studien zur Ouvertüre nach 1789 by Roman Schnur pp. 720–721 from Historische Zeitschrift, Volume 238, Issue # 3 June 1984.

- Review of Der italienische Faschismus. Probleme und Forschungstendenzen pp. 469–471 from Historische Zeitschrift, Volume 240, Issue #2 April 1985.

- “Zusammenbruch und Neubeginn: Die Bedeutung des 8. Mai 1945” pp. 296–303 from Zeitschrift für Politik, Volume 32, Issue #3, 1985.

- “Philosophische Geschichtsschreibung heute?” pp. 265–289 from Historische Zeitschrift, Volume 242, Issue #2, April 1986.

- “Une Querelle D'Allemandes? Du Passe Qui Ne Veut Pas S'Effacer” pp. 36–39 from Documents, Volume 1, 1987.

- Review: Ein Höhepunkt der Heidegger-Kritik? Victor Farias' Buch "Heidegger et le Nazisme" pp. 95–114 from Historische Zeitschrift, Volume 247, Issue #1, August 1988.

- "Das Vor-Urteil als "Strenge Wissenschaft." Zu den Rezensionen von Hans Mommsen und Wolfgang Schieder” pp. 537–551 from Geschichte und Gesellschaft, Volume 15, Issue #4, 1989.

- Review of The Politics of Being The Political Thought of Martin Heidegger by Richard Wolin pp. 123–124 from Historische Zeitschrift, Volume 258, Issue # 1 February 1994.

- "Die historisch-genetische Version der Totalitarismusthorie: Ärgernis oder Einsicht?" pp. 111–122 from Zeitschrift für Politik, Volume 43, Issue #2, 1996.

- Historische Existenz: Zwischen Anfang und Ende der Geschichte?, Munich: Piper 1998, ISBN: 978-3-492-04070-9.

- Les Fondements historiques du national-socialisme, Paris: Editions du Rocher, 2002.

- L'eredità del nazionalsocialismo, Rome: Di Renzo Editore, 2003.

- co-written with Siegfried Gerlich Einblick in ein Gesamtwerk, Edition Antaios: Dresden 2005, ISBN: 978-3-935063-61-6.

- Die dritte radikale Widerstandsbewegung: Der Islamismus, Landt Verlag, Berlin 2009, ISBN: 978-3-938844-16-8.