Dream of the Red Chamber facts for kids

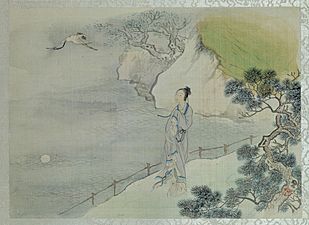

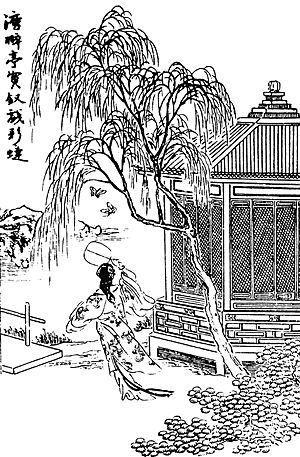

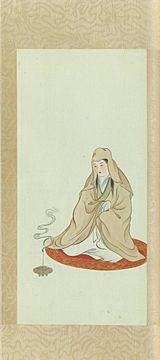

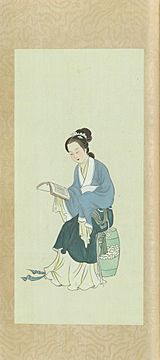

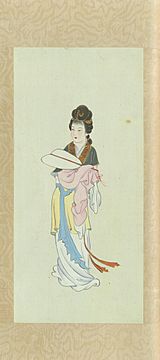

A scene from the novel, painted by Xu Baozhuan (1810–1873)

|

|

| Author | Cao Xueqin |

|---|---|

| Original title | 紅樓夢 |

| Country | Qing China |

| Language | Chinese |

| Genre | Novel, Family saga |

| Set in | China |

|

Publication date

|

mid-18th century (manuscripts) 1791 (first printed edition) |

|

Published in English

|

1868, 1892; 1973–1980 (1st complete English translation) |

| Media type | Scribal copies/Print |

| 895.1348 | |

| Dream of the Red Chamber | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

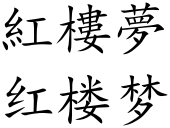

"Dream of the Red Chamber" in Traditional (top) and Simplified (bottom) Chinese characters

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 紅樓夢 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 红楼梦 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Alternative Chinese name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 石頭記 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 石头记 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | "Records of the Stone" | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Dream of the Red Chamber (Honglou Meng) or The Story of the Stone (Shitou Ji) is a novel composed by Cao Xueqin in the middle of the 18th century. One of the Four Great Classical Novels of Chinese literature, it is known for its psychological scope, and its observation of the worldview, aesthetics, life-styles, and social relations of 18th-century China.

The intricate strands of its plot depict the rise and decline of a family much like Cao's own and, by extension, of the dynasty itself. Cao depicts the power of the father over the family, but the novel is intended to be a memorial to the women he knew in his youth: friends, relatives and servants. At a more profound level, the author explores religious and philosophical questions, and the writing style includes echoes of the plays and novels of the late Ming, as well as poetry from earlier periods.

Cao apparently began composing it in the 1740s and worked on it until his death in 1763 or 1764. Copies of his uncompleted manuscript circulated in Cao's social circle, under the title Story of a Stone in slightly varying versions of eighty chapters. It was not published until nearly three decades after Cao's death, when Gao E and Cheng Weiyuan (程偉元), edited the first and second printed editions under the title Dream of the Red Chamber in 1791–92, adding 40 chapters. It is still debated whether Gao and Cheng composed these chapters themselves and the extent to which they did or did not represent Cao's intentions. Their 120 chapter edition became the most widely circulated version. The title has also been translated as Red Chamber Dream and A Dream of Red Mansions. "Redology" is the field of study devoted to the novel.

Contents

Language

The novel is composed in written vernacular (baihua) rather than Classical Chinese (wenyan). Cao Xueqin was well versed in Chinese poetry and in Classical Chinese, having written tracts in the semi-wenyan style, while the novel's dialogue is written in the Beijing Mandarin dialect, which was to become the basis of modern spoken Chinese. In the early 20th century, lexicographers used the text to establish the vocabulary of the new standardised language and reformers used the novel to promote the written vernacular.

History

Textual history

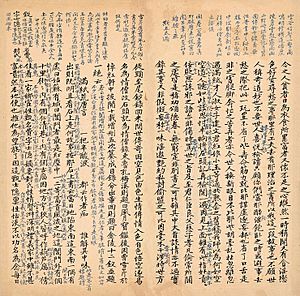

Dream of the Red Chamber has a complex textual history that has long been the subject of scholarly debate and conjecture. It is definitively known that Cao Xueqin, a member of an eminent family that had served the Qing dynasty emperors but whose fortunes had begun to decline, began writing Dream of the Red Chamber in the 1740s. By the time of Cao's death in 1763 or 1764, hand-copied manuscripts of the novel's first 80 chapters had begun circulating, and Cao may have made early drafts of the remaining chapters. These hand-copied manuscripts circulated first among his personal friends and a growing circle of aficionados, then eventually on the open market where they sold for large sums of money. The first printed version, published by Cheng Weiyuan and Gao E in 1791, contains edits and revisions not authorized by the author. It is possible that Cao destroyed the last chapters or that at least parts of Cao's original ending were incorporated into the 120 chapter Cheng-Gao versions, with Gao E's "careful emendations" of Cao's draft.

"Rouge" versions

Up until 1791, the novel circulated in hand-copied manuscripts. Even amongst some 12 independent surviving manuscripts, small differences in some characters, rearrangements and possible rewritings cause the texts to vary a little. The earliest manuscripts end abruptly at the latest at the 80th chapter. The earlier versions contain comments and annotations in red or black ink from unknown commentators. These commentators' remarks reveal much about the author as a person, and it is now believed that some of them may even be members of Cao Xueqin's own family. The most prominent commentator is Zhiyanzhai, who revealed much of the interior structuring of the work and the original manuscript ending, now lost. These manuscripts, the most textually reliable versions, are known as "Rouge versions" (zhī běn 脂本).

The early 80 chapters brim with prophecies and dramatic foreshadowings that give hints as to how the book would continue. For example, it is obvious that Lin Daiyu will eventually die in the course of the novel; that Baoyu and Baochai will marry; that Baoyu will become a monk. A branch of Redology, known as tànyì xué (探佚學), is focused on recovering the lost manuscript ending, based on the commentators' annotations in the Rouge versions, as well as the internal foreshadowings in the earlier 80 chapters.

Several early manuscripts are still extant. At the present, the "Jiaxu manuscript" (dating to 1754) is held in the Shanghai Museum, the "Jimao manuscript" (1759) is held in the National Library of China, and the "Gengchen manuscript" (1760) is held in the library of Peking University. Beijing Normal University and the Institute of Oriental Studies of the Russian Academy of Sciences both also held manuscripts of the novel that predate the first printed edition of 1791.

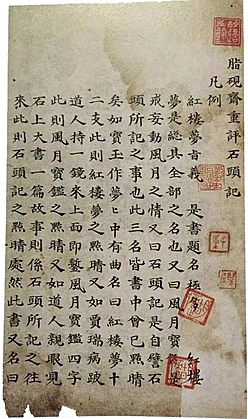

Cheng–Gao versions

In 1791, Gao E and Cheng Weiyuan brought out the novel's first printed edition. This was also the first "complete" edition of The Story of the Stone, which they printed as the Illustrated Dream of the Red Chamber (Xiùxiàng Hóng Lóu Mèng 繡像紅樓夢). While the original Rouge manuscripts have eighty chapters, the 1791 edition completed the novel in 120 chapters. The first 80 chapters were edited from the Rouge versions, but the last 40 were newly published.

In 1792, Cheng and Gao published a second edition correcting editorial errors of the 1791 version. In the 1791 prefaces, Cheng claimed to have put together an ending based on the author's working manuscripts.

The debate over the last 40 chapters and the 1791–92 prefaces continues to this day. Many modern scholars believe these chapters were a later addition. Hu Shih, in his Studies on A Dream of the Red Chamber (1921) argued that these chapters were written by Gao E, citing the foreshadowing of the main characters' fates in Chapter 5, which differs from the ending of the 1791 Cheng-Gao version. However, during the mid-20th century, the discovery of a 120 chapter manuscript that dates well before 1791 further complicated the questions regarding Gao E and Cheng Weiyuan's involvement—whether they simply edited or actually wrote the continuation of the novel. Though it is unclear if the last 40 chapters of the discovered manuscript contained the original works of Cao, Irene Eber found the discovery "seems to confirm Cheng and Gao's claim that they merely edited a complete manuscript, consisting of 120 chapters, rather than actually writing a portion of the novel".

The book is usually published and read in Cheng Weiyuan and Gao E's 120 chapter version. Some modern editions, such as Zhou Ruchang's, do not include the last 40 chapters.

In 2014, three researchers using data analysis of writing styles announced that "Applying our method to the Cheng–Gao version of Dream of the Red Chamber has led to convincing if not irrefutable evidence that the first 80 chapters and the last 40 chapters of the book were written by two different authors."

In 2020, Zhang Qingshan, the president of the academic organization Society of the Dream of the Red Chamber, stated that although the authorship of the novel's last 40 chapters remains uncertain, it is unlikely Gao E was the one who wrote them.

Plot summary

In the novel's frame story, a sentient Stone, left over when the goddess Nüwa mended the heaven aeons ago, wants to enjoy the pleasures of the "red dust" (the mundane world). The Stone begs a Taoist priest and a Buddhist monk to take it with them to see the world. The Stone, along with a companion (in Cheng-Gao versions they are merged into the same character), is then given a chance to learn from human existence, and enters the mortal realm, reborn as Jia Baoyu ("Precious Jade") – thus "The Story of the Stone".

The novel provides a detailed, episodic record of life in the two branches of the wealthy, aristocratic Jia (賈) clan—the Rongguo House (榮國府) and the Ningguo House (寧國府)—who reside in large, adjacent family compounds in the capital. The capital, however, is not named, and the first chapter insists that the dynasty is indeterminate. The ancestors of the two families were made Chinese nobility and given imperial titles, and as the novel begins the two houses are among the most illustrious families in the city. One of the Jia daughters is made a Royal Consort, and to suitably receive her, the family constructs the Daguanyuan, a lush landscaped garden, the setting for much of subsequent action. The novel describes the Jias' wealth and influence in great naturalistic detail, and charts the Jias' fall from the height of their prestige, following some thirty main characters and over four hundred minor ones.

As the carefree adolescent male heir of the family, Baoyu in this life has a special bond with his sickly cousin Lin Daiyu, who shares his love of music and poetry. Baoyu, however, is predestined to marry another cousin, Xue Baochai, whose grace and intelligence exemplify an ideal woman, but with whom he lacks an emotional connection. The romantic rivalry and friendship among the three characters against the backdrop of the family's declining fortunes form the central story.

Characters

Dream of the Red Chamber contains an extraordinarily large number of characters: nearly 40 are considered major characters, and there are over 400 additional ones. The novel is also known for the complex portraits of its many women characters. According to Lu Xun in the appendix to A Brief History of Chinese Fiction, Dream of the Red Chamber broke every conceivable thought and technique in traditional Chinese fiction; its realistic characterization presents thoroughly human characters who are neither "wholly good nor wholly bad", but who seem to inhabit part of the real world.

The names of the characters present a challenge to the translator, since many of them convey meaning. David Hawkes left the names of the masters, mistresses, and their family members in pinyin (Jia Zheng and Lady Wang, for instance); translated the meanings of the servants's names, (such as Aroma and Skybright); and put the names of the Daoists and Buddhists into Latin (Sapientia); and those of actors and actresses into French.

Jia Baoyu and the Twelve Beauties of Jinling

- Jia Baoyu (traditional Chinese: 賈寶玉; simplified Chinese: 贾宝玉; pinyin: Jiǎ Bǎoyù; Wade–Giles: Chia Pao-yu; literally "Precious Jade")

The main protagonist is about 12 or 13 years old when introduced in the novel. The adolescent son of Jia Zheng and his wife, Lady Wang, and born with a piece of luminescent jade in his mouth (the Stone), Baoyu is the heir apparent to the Rongguo House. Frowned on by his strict Confucian father, Baoyu reads Zhuangzi and Romance of the Western Chamber on the sly, rather than the Four Books of classic Chinese education. Baoyu is highly intelligent, but dislikes the fawning bureaucrats who frequent his father's house. A sensitive and compassionate individual, he has a special relationship with many of the women in the house. - Lin Daiyu (Chinese: 林黛玉; pinyin: Lín Dàiyù; Wade–Giles: Lin Tai-yu; literally "Blue-black Jade")

Jia Baoyu's younger first cousin and his true love. She is the daughter of Lin Ruhai (林如海), an official in the lucrative Yangzhou salt commission, and Lady Jia Min (賈敏), Baoyu's paternal aunt. She is an icon of spirituality and intelligence: beautiful, sentimental, sarcastic, self-assured, an accomplished poet, but subject to fits of jealousy. She suffers from a respiratory ailment. In the frame story, Baoyu, in his previous incarnation as the Deity Shenying, watered Fairy Crimson Pearl, Daiyu's incarnation. The purpose of her mortal reincarnation is to repay Baoyu with tears. The novel proper starts in Chapter 3 with Daiyu's arrival at the Rongguo House shortly after the death of her mother. - Xue Baochai (traditional Chinese: 薛寶釵; simplified Chinese: 薛宝钗; pinyin: Xuē Bǎochāi; Wade–Giles: Hsueh Pao-chai; literally "Jeweled Hair Pin")

Jia Baoyu's other first cousin. The only daughter of Aunt Xue (薛姨媽}), sister to Baoyu's mother, Baochai is a foil to Daiyu. Where Daiyu is unconventional and sincere, Baochai is worldly-wise and very tactful: a model Chinese feudal maiden. The novel describes her as beautiful and ambitious. Baochai has a round face, fair skin, large eyes, and, some would say, a more voluptuous figure in contrast to Daiyu's slender willowy daintiness. Baochai carries a golden locket with her which contains words given to her in childhood by a Buddhist monk. Baochai's golden locket and Baoyu's jade contain inscriptions that appear to complement one another perfectly in the material world. Her marriage to Baoyu is seen in the book as predestined. - Jia Yuanchun (traditional Chinese: 賈元春; simplified Chinese: 贾元春; pinyin: Jiǎ Yuánchūn; Wade–Giles: Chia Yuan-chun; literally "First Spring")

Baoyu's elder sister by about a decade. Originally one of the ladies-in-waiting in the imperial palace, Yuanchun later becomes an Imperial Consort, having impressed the Emperor with her virtue and learning. Her illustrious position as a favorite of the Emperor marks the height of the Jia family's powers. Despite her prestigious position, Yuanchun feels imprisoned within the imperial palace, and dies at the age of forty. The name of four sisters together "Yuan-Ying-Tan-Xi" is a homophone with "Supposed to sigh". - Jia Tanchun (traditional Chinese: 賈探春; simplified Chinese: 贾探春; pinyin: Jiǎ Tànchūn; Wade–Giles: Chia Tan-chun; literally "Seeking Spring")

Baoyu's younger half-sister by Concubine Zhao. Extremely outspoken, she is almost as capable as Wang Xifeng. Wang Xifeng herself compliments her privately, but laments that she was "born in the wrong womb", since concubine children are not respected as much as those by first wives. She is also a very talented poet. Tanchun is nicknamed "Rose" for her beauty and her prickly personality. She later marries into a military family on the South Sea far away from home. - Shi Xiangyun (traditional Chinese: 史湘雲; simplified Chinese: 史湘云; pinyin: Shǐ Xiāngyún; Wade–Giles: Shih Hsiang-yun; literally "Xiang River Clouds")

Jia Baoyu's younger second cousin. Grandmother Jia's grandniece. Orphaned in infancy, she grows up under her wealthy paternal uncle and aunt who treats her unkindly. In spite of this Xiangyun is openhearted and cheerful. A comparatively androgynous beauty, Xiangyun looks good in men's clothes (once she put on Baoyu's clothes and Grandmother Jia thought she was a man), and loves to drink. She is forthright and without tact, but her forgiving nature takes the sting from her casually truthful remarks. She is well educated and as talented a poet as Daiyu or Baochai. Her young husband dies shortly after their marriage. She vows to be a faithful widow for the rest of her life. - Miaoyu (Chinese: 妙玉; pinyin: Miàoyù; Wade–Giles: Miao-yu; literally "Wonderful/Clever Jade"; Hawkes/Minford translation: Adamantina)

A young nun from Buddhist cloisters of the Rong-guo house. Although beautiful and learned, she is aloof, haughty, unsociable, and has an obsession with cleanliness. The novel says she was compelled by her illness to become a nun, and shelters herself under the nunnery to dodge political affairs. Her fate is not known after her abduction by bandits. - Jia Yingchun (traditional Chinese: 賈迎春; simplified Chinese: 贾迎春; pinyin: Jiǎ Yíngchūn; Wade–Giles: Chia Ying-chun; literally "Welcoming Spring")

Second female family member of the generation of the Jia household after Yuanchun, Yingchun is the daughter of Jia She, Baoyu's uncle and therefore his elder first cousin. A kind-hearted, weak-willed person, Yingchun is said to have a "wooden" personality and seems rather apathetic toward all worldly affairs. Although very pretty and well-read, she does not compare in intelligence and wit to any of her cousins. Yingchun's most famous trait, it seems, is her unwillingness to meddle in the affairs of her family. Eventually Yingchun marries an official of the imperial court, her marriage being merely one of her father's desperate attempts to raise the declining fortunes of the Jia family. - Jia Xichun (traditional Chinese: 賈惜春; simplified Chinese: 贾惜春; pinyin: Jiǎ Xīchūn; Wade–Giles: Chia Hsi-chun; literally "Treasuring Spring")

Baoyu's younger cousin from the Ningguo House, but brought up in the Rongguo House. A gifted painter, she is also a devout Buddhist. She is the young sister of Jia Zhen, head of the Ningguo House. At the end of the novel, after the fall of the house of Jia, she gives up her worldly concerns and becomes a Buddhist nun. She is the second youngest of Jinling's Twelve Beauties, described as a pre-teen in most parts of the novel. - Wang Xifeng (traditional Chinese: 王熙鳳; simplified Chinese: 王熙凤; pinyin: Wáng Xīfèng; Wade–Giles: Wang Hsi-feng; literally "Splendid Phoenix"), alias Sister Feng.

Baoyu's elder cousin-in-law, young wife to Jia Lian (who is Baoyu's paternal first cousin), niece to Lady Wang. Xifeng is hence related to Baoyu both by blood and marriage. A handsome woman, Xifeng is capable, clever, humorous, and, at times, vicious and cruel. Undeniably the most worldly woman in the novel, Xifeng is in charge of the daily running of the Rongguo household and wields economic as well as political power within the family. Xifeng keeps both Lady Wang and Grandmother Jia entertained with her jokes and chatter. By playing the role of the perfect filial daughter-in-law, she rules the household with an iron fist. Xifeng can be kind-hearted toward the poor and helpless or cruel enough to kill. She makes a fortune by investing in loan sharking rather than maintaining the family estate and brings about the downfall of the family. She dies soon after the family assets are seized by the government. - Jia Qiaojie (traditional Chinese: 賈巧姐; simplified Chinese: 贾巧姐; pinyin: Jiǎ Qiǎojiě; Wade–Giles: Chia Chiao-chieh)

Wang Xifeng's and Jia Lian's daughter. She is a child through much of the novel. After the fall of the house of Jia, in the version of Gao E and Cheng Weiyuan, she marries the son of a wealthy rural family introduced by Granny Liu and goes on to lead a happy, uneventful life in the countryside. - Li Wan (traditional Chinese: 李紈; simplified Chinese: 李纨; pinyin: Lǐ Wán; Wade–Giles: Li Wan; literally "White Silk")

Baoyu's elder sister-in-law, widow of Baoyu's deceased elder brother, Jia Zhu (賈珠). Her primary task is to bring up her son Lan and watch over her female cousins. The novel portrays Li Wan, a young widow in her late twenties, as a mild-mannered woman with no wants or desires, the perfect Confucian ideal of a proper mourning widow. She eventually attains high social status due to the success of her son at the Imperial Exams, but the novel sees her as a tragic figure because she wasted her youth upholding the strict standards of behavior. - Qin Keqing (Chinese: 秦可卿; pinyin: Qín Kěqīng; Wade–Giles: Ch'in K'o-ching;a homophone with "look down upon love")

Daughter-in-law to Jia Zhen. Of all the characters in the novel, the circumstances of her life and early death are amongst the most mysterious. Apparently a very beautiful and flirtatious woman, she carried on an affair with her father-in-law and dies before the second quarter of the novel. Her bedroom is bedecked with priceless artifacts belonging to extremely sensual women, both historical and mythological.

Other main characters

- Grandmother Jia (traditional Chinese: 賈母; simplified Chinese: 贾母; pinyin: Jiǎmǔ), née Shi.

Also called the Matriarch or the Dowager, the daughter of Marquis Shi of Jinling. Grandmother to both Baoyu and Daiyu, she is the highest living authority in the Rongguo house and the oldest and most respected of the entire clan, yet also a doting person. She has two sons, Jia She and Jia Zheng, and a daughter, Min, Daiyu's mother. Daiyu is brought to the house of the Jias at the insistence of Grandmother Jia, and she helps Daiyu and Baoyu bond as childhood playmates and, later, kindred spirits. She distributes her savings among her relatives after the seizure of their properties by the government shortly before her death. - Jia She (traditional Chinese: 賈赦; simplified Chinese: 贾赦; pinyin: Jiǎ Shè; Wade–Giles: Chia Sheh)

The elder son of the Dowager. He is the father of Jia Lian and Jia Yingchun. He is a treacherous and greedy man. He is jealous of his younger brother whom his mother favors. He is later stripped of his title and banished by the government. - Jia Zheng (traditional Chinese: 賈政; simplified Chinese: 贾政; pinyin: Jiǎ Zhèng; Wade–Giles: Chia Cheng)

Baoyu's father, the younger son of the Dowager. He is a disciplinarian and Confucian scholar. Afraid his one surviving heir will turn bad, he imposes strict rules on his son, and uses occasional corporal punishment. He has a wife, Lady Wang, and one concubine: Zhao. He is a Confucian scholar who tries to live life as an upright and decent person, but out of touch with reality and a hands-off person at home and in court. - Jia Lian (traditional Chinese: 賈璉; simplified Chinese: 贾琏; pinyin: Jiǎ Liǎn; Wade–Giles: Chia Lien)

Xifeng's husband and Baoyu's paternal elder cousin. He and his wife are in charge of most hiring and monetary allocation decisions, and often fight over this power. He is a cad with a flawed character but still has a conscience. - Xiangling (Chinese: 香菱; pinyin: Xiāng Líng; literally "Fragrant Water caltrop"; Hawkes/Minford translation: Caltrop) – the Xues' maid, born Zhen Yinglian (甄英蓮, a homophone with "deserving pity"), the kidnapped and lost daughter of Zhen Shiyin (甄士隱, a homophone with "Hiding the truth"), the country gentleman in Chapter 1. Her name is changed to Qiuling (秋菱) by Xue Pan's spoiled wife, Xia Jingui (夏金桂) who is jealous of her and tries to poison her. Xue Pan makes her the lady of the house after Jingui's death. She soon dies while giving birth.

- Ping'er (Chinese: 平兒; literally "Peace"; Hawkes/Minford translation: Patience)

Xifeng's chief maid and personal confidante; also concubine to Xifeng's husband, Jia Lian. Originally Xifeng's maid in the Wang household, she follows Xifeng as part of her dowry when Xifeng marries into the Jia household. She handles her troubles with grace, assists Xifeng capably and appears to have the respect of most of the household servants. She is also one of the very few people who can get close to Xifeng. She wields considerable power in the house as Xifeng's most trusted assistant, but uses her power sparingly and justly. She is supremely loyal to her mistress, but more soft-hearted and sweet-tempered. - Xue Pan (Chinese: 薛蟠; pinyin: Xuē Pán; Wade–Giles: Hsueh Pan; literally "to Coil (as a dragon)")

Baochai's older brother, a dissolute, idle rake who was a local bully in Jinling. He was known for his amorous exploits with both men and women. Not particularly well educated, he once killed a man over a servant-girl (Xiangling) and had the manslaughter case hushed up with money. - Granny Liu (traditional Chinese: 劉姥姥; simplified Chinese: 刘姥姥; pinyin: Liú Lǎolao)

A country rustic and distant relation to the Wang family, who provides a comic contrast to the ladies of the Rongguo House during two visits. She eventually rescues Qiaojie from her maternal uncle, who wanted to sell her. - Lady Wang (Chinese: 王夫人; pinyin: Wáng Fūren)

A Buddhist, primary wife of Jia Zheng. Daughter of one of the four most prominent families of Jinling. Because of her purported ill-health, she hands over the running of the household to her niece, Xifeng, as soon as the latter marries into the Jia household, although she retains overall control over Xifeng's affairs so that the latter always has to report to her. Although Lady Wang appears to be a kind mistress and a doting mother, she can in fact be cruel and ruthless when her authority is challenged. She pays a great deal of attention to Baoyu's maids to make sure that Baoyu does not develop romantic relationships with them. - Aunt Xue (traditional Chinese: 薛姨媽; simplified Chinese: 薛姨妈; pinyin: Xuē Yímā), née Wang

Baoyu's maternal aunt, mother to Pan and Baochai, sister to Lady Wang. She is kindly and affable for the most part, but finds it hard to control her unruly son. - Hua Xiren (traditional Chinese: 花襲人; simplified Chinese: 花袭人; pinyin: Huā Xírén; literally "Flower Assails Men"; Hawkes/Minford translation: Aroma)

Baoyu's principal maid and his unofficial concubine. While she still has standing as the Dowager's maid, the Dowager gave her to Baoyu so, in practice, Xiren is his maid. After Baoyu's disappearance, she unknowingly marries actor Jiang Yuhan, one of Baoyu's friends.

- Qingwen (Chinese: 晴雯; pinyin: Qíngwén; literally "Sunny Multicolored Clouds"; Hawkes/Minford translation: Skybright)

Baoyu's personal maid. Brash, haughty and the most beautiful maid in the household, Qingwen is said to resemble Daiyu very strongly. Of all of Baoyu's maids, she is the only one who dares to argue with Baoyu when reprimanded, but is also extremely devoted to him. Qingwen dies of an illness shortly after leaving the Jia household. - Yuanyang (traditional Chinese: 鴛鴦; simplified Chinese: 鸳鸯; pinyin: Yuānyang; literally "Pair of Mandarin Ducks"; Hawkes/Minford translation: Faithful)

The Dowager's chief maid. She rejects a marriage proposal (as concubine) to the lecherous Jia She, Grandmother Jia's eldest son and dies right after the Dowager's death. - Mingyan (traditional Chinese: 茗煙; simplified Chinese: 茗烟; pinyin: Míngyān; literally "Tea Vapor"; Hawkes/Minford translation: Tealeaf)

Baoyu's page boy. Knows his master like the back of his hand. - Zijuan (traditional Chinese: 紫鵑; simplified Chinese: 紫鹃; pinyin: Zǐjuān; Wade–Giles: Tzu-chuan; literally "Purple Rhododendron or Cuckoo"; Hawkes/Minford translation: Nightingale)

Daiyu's faithful maid, ceded by the Dowager to her granddaughter. She later becomes a nun to serve Jia Xichun. - Xueyan (Chinese: 雪雁; pinyin: Xuěyàn; Hawkes/Minford translation: Snowgoose)

Daiyu's other maid. She came with Daiyu from Yangzhou, and comes across as a young, sweet girl. She is asked to accompany the veiled bride Baochai to trick Baoyu into believing that he is marrying Daiyu. - Concubine Zhao (traditional Chinese: 趙姨娘; simplified Chinese: 赵姨娘; pinyin: Zhào Yíniáng)

A concubine of Jia Zheng. She is the mother of Jia Tanchun and Jia Huan, Baoyu's half-siblings. She longs to be the mother of the head of the household, which she does not achieve. She plots to murder Baoyu and Xifeng with black magic, and it is believed that her plot cost her own life.

Notable minor characters

- Qin Zhong (秦鐘, a homophone with "great lover") – His elder sister is Qin Keqing, Baoyu's nephew's wife, and so he is technically a generation younger than Baoyu. Both he and Qin Keqing are the adopted children of Qin Ye(秦業). The two boys enroll in the Jia clan's school together and he becomes Baoyu's best friend. The novel leaves open the possibility that things might have gone beyond innocent friendship. Qin Zhong and the novice Zhineng (智能, "Intelligent"; "Sapientia" in the Hawkes translation) fall in love but Qin Zhong dies.

- Jia Lan (賈蘭) – Son of Baoyu's deceased older brother Jia Zhu and his virtuous wife Li Wan. Jia Lan is an appealing child throughout the book and at the end succeeds in the imperial examinations to the credit of the family.

- Jia Zhen (賈珍) – Head of the Ningguo House, the elder branch of the Jia family. He has a wife, Lady You, a younger sister, Jia Xichun, and many concubines. He is extremely greedy and the unofficial head of the clan, since his father has retired.

- Lady You (尤氏) – Wife of Jia Zhen. She is the sole mistress of the Ningguo House.

- Jia Rong (賈蓉) – Jia Zhen's son. He is the husband of Qin Keqing. An exact copy of his father, he is the Cavalier of the Imperial Guards.

- Second Sister You (尤二姐) – Jia Lian takes her in secret as his lover. Though a kept woman before she was married, after her wedding she becomes a faithful and doting wife.

- Lady Xing (邢夫人) – Jia She's wife. She is Jia Lian's stepmother.

- Jia Huan (賈環) – Son of Concubine Zhao. He and his mother are both reviled by the family, and he carries himself like a kicked dog. He shows his malignant nature by spilling candle wax, intending to blind his half-brother Baoyu.

- Sheyue (麝月; Hawkes/Minford translation: Musk) — Baoyu's main maid after Xiren and Qingwen. She is beautiful and caring, a perfect complement to Xiren.

- Qiutong (秋桐) — Jia Lian's other concubine. Originally a maid of Jia She, she is given to Jia Lian as a concubine. She is a very proud and arrogant woman.

- Sister Sha (傻大姐) – A maid who does rough work for the Dowager. She is guileless but amusing and caring. In the Gao E and Cheng Weiyuan version, she unintentionally informs Daiyu of Baoyu's secret marriage plans.

Themes

Honglou meng is a book about enlightenment [or awakening]. ... A man in his life experiences several decades of winter and summer. The most sagacious and wise is certainly not submerged in considerations of loss and gain. However, the experiences of prosperity and decline, coming together and dispersing [of family members and friends] are too common; how can his mind be like wood and stone, without being moved by all this? In the beginning there is a profusion of intimate feelings, which is followed by tears and lamentations. Finally, there is a time when one feels that everything he does is futile. At this moment, how can he not be enlightened?

The opening chapter of the novel describes a great stone archway and on either side a couplet is inscribed:

假作真時真亦假,

無為有處有還無。

Truth becomes fiction when the fiction's true;

Real becomes not-real where the unreal's real.

This couplet is later reiterated, however this time as:

假去真來真勝假,

無原有是有非無。

When Fiction departs and Truth appears, Truth prevails;

Though Not-real was once Real, the Real is never unreal.

As one critic points out, the couplet signifies "not a hard and fast division between truth and falsity, reality and illusion, but the impossibility of making such distinctions in any world, fictional or actual." This theme is further reflected in the name of the main family, Jia (賈, pronounced jiǎ), which is a homophone with the character jiǎ 假, meaning false or fictitious; this is mirrored the surname of the other main family, Zhen (甄, pronounced zhēn), a homophone for the word "real" (真). It is suggested that the novel is both a realistic reflection and a fictional or "dream" version of Cao's own family.

Early Chinese critics identified its two major themes as those of romantic love, and of the transitoriness of earthly material values, as outlined in Buddhist and Taoist philosophies. Later scholars echoed the philosophical aspects of love and its transcendent power as depicted in the novel. One remarked that the novel is a remarkable example of the "dialectic of dream and reality, art and life, passion and enlightenment, nostalgia and knowledge."

The novel also vividly depicts Chinese material culture, such as medicine, cuisine, tea culture, festivities, proverbs, mythology, Confucianism, Buddhism, Taoism, filial piety, opera, music, architecture, funeral rites, painting, classic literature and the Four Books. Among these, the novel is particularly notable for its grand use of poetry.

Since the establishment of Cao Xueqin as the novel's author, its autobiographical aspects have come to the fore. Cao Xueqin's clan was similarly raided in real life, and suffered a steep decline. Marxist interpretation starting in the New Culture Movement saw the novel as exposing feudal society's corruption and emphasized the clashes between the classes. Since the 1980s, critics have embraced the novel's richness and aesthetics in a more multicultural context.

In the title Hóng lóu Mèng (紅樓夢, literally "Red Chamber Dream"), "red chamber" can refer to the sheltered chambers where the daughters of a prominent family reside. It also refers to Baoyu's dream in chapter five, set in a "red chamber", a dream where the fates of many of the characters are foreshadowed. "Mansion" is one of the definitions of the Chinese character "樓" (lóu), but the scholar Zhou Ruchang writes that in the phrase hónglóu it is more accurately translated as "chamber".

See also

In Spanish: Sueño en el pabellón rojo para niños

In Spanish: Sueño en el pabellón rojo para niños