Diplomatic history facts for kids

Diplomatic history deals with the history of international relations between states. Diplomatic history can be different from international relations in that the former can concern itself with the foreign policy of one state while the latter deals with relations between two or more states. Diplomatic history tends to be more concerned with the history of diplomacy, but international relations concern more with current events and creating a model intended to shed explanatory light on international politics.

History

Europe

The ability to practice diplomacy is one of the defining elements of a state, and diplomacy has been practiced since the first city-states were formed millennia ago. For most of human history diplomats were sent only for specific negotiations, and would return immediately after their mission concluded. Diplomats were usually relatives of the ruling family or of very high rank in order to give them legitimacy when they sought to negotiate with the other state.

One notable exception involved the relationship between the Pope and the Byzantine Emperor; papal agents, called apocrisiarii, were permanently resident in Constantinople. After the 8th century, however, conflicts between the Pope and Emperor (such as the Iconoclastic controversy) led to the breaking of close ties.

Modern diplomacy's origins are often traced to the states of Northern Italy in the early Renaissance, with the first embassies being established in the thirteenth century. Milan played a leading role, especially under Francesco Sforza who established permanent embassies to the other city states of Northern Italy. It was in Italy that many of the traditions of modern diplomacy began, such as the presentation of an ambassadors credentials to the head of state.

From Italy the practice was spread to the other European powers. Milan was the first to send a representative to the court of France in 1455. However, Milan refused to host French representatives fearing espionage and that the French representatives would intervene in its internal affairs. As foreign powers such as France and Spain became increasingly involved in Italian politics the need to accept emissaries was recognized. Soon the major European powers were exchanging representatives. Spain was the first to send a permanent representative; it appointed an ambassador to the Court of England in 1487. By the late 16th century, permanent missions became customary. The Holy Roman Emperor, however, did not regularly send permanent legates, as they could not represent the interests of all the German princes (who were in theory subordinate to the Emperor, but in practice independent).

During that period the rules of modern diplomacy were further developed. The top rank of representatives was an ambassador. At that time an ambassador was a nobleman, the rank of the noble assigned varying with the prestige of the country he was delegated to. Strict standards developed for ambassadors, requiring they have large residences, host lavish parties, and play an important role in the court life of their host nation. In Rome, the most prized posting for a Catholic ambassador, the French and Spanish representatives would have a retinue of up to a hundred. Even in smaller posts, ambassadors were very expensive. Smaller states would send and receive envoys, who were a rung below ambassador. Somewhere between the two was the position of minister plenipotentiary.

Diplomacy was a complex affair, even more so than now. The ambassadors from each state were ranked by complex levels of precedence that were much disputed. States were normally ranked by the title of the sovereign; for Catholic nations the emissary from the Vatican was paramount, then those from the kingdoms, then those from duchies and principalities. Representatives from republics were considered the lowest of the low. Determining precedence between two kingdoms depended on a number of factors that often fluctuated, leading to near-constant squabbling.

Ambassadors, nobles with little foreign experience and no expectation of a career in diplomacy, needed to be supported by large embassy staff. These professionals would be sent on longer assignments and would be far more knowledgeable than the higher-ranking officials about the host country. Embassy staff would include a wide range of employees, including some dedicated to espionage. The need for skilled individuals to staff embassies was met by the graduates of universities, and this led to a great increase in the study of international law, modern languages, and history at universities throughout Europe.

At the same time, permanent foreign ministries began to be established in almost all European states to coordinate embassies and their staffs. These ministries were still far from their modern form, and many of them had extraneous internal responsibilities. Britain had two departments with frequently overlapping powers until 1782. They were also far smaller than they are currently. France, which boasted the largest foreign affairs department, had only some 70 full-time employees in the 1780s.

The elements of modern diplomacy slowly spread to Eastern Europe and Russia, arriving by the early eighteenth century. The entire edifice would be greatly disrupted by the French Revolution and the subsequent years of warfare. The revolution would see commoners take over the diplomacy of the French state, and of those conquered by revolutionary armies. Ranks of precedence were abolished. Napoleon also refused to acknowledge diplomatic immunity, imprisoning several British diplomats accused of scheming against France.

After the fall of Napoleon, the Congress of Vienna of 1815 established an international system of diplomatic rank. Disputes on precedence among nations (and therefore the appropriate diplomatic ranks used) persisted for over a century until after World War II, when the rank of ambassador became the norm. In between that time, figures such as the German Chancellor Otto von Bismark were renowned for international diplomacy.

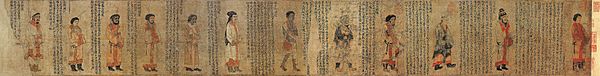

Asia

Diplomatic traditions outside of Europe were more or less very different. A feature necessary for diplomacy is the existence of a number of states of somewhat equal power, as existed in Italy during the Renaissance, and in Europe for much of the modern period. By contrast, in Asia and the Middle East, China and the Ottoman Empire were reluctant to practice bilateral diplomacy as they viewed themselves to be unquestionably superior to all their neighbours (hence, set up smaller nations as tributaries and vassals). The Ottoman Turks, for instance, would not send missions to other states, expecting representatives to come to Istanbul. It would not be until the nineteenth century that the Ottoman Empire established permanent embassies in other capitals. Likewise, the Koreans and Japanese during the Chinese Tang Dynasty (618–907 AD) looked to the Chinese capital of Chang'an as the hub of civilization and emulated its central bureaucracy as the pristine model of governance. The Japanese sent frequent embassies to China in this period, although they halted these trips in 894 during the Tang's imminent collapse. However, there were periods of Chinese history where China was weakened and threatened enough so that skillful international diplomacy was necessary.

One of the earliest realists in international relations theory was the 6th century BC military strategist Sun Tzu, author of The Art of War. He lived during the Warring States Period (403 BC-221 BC), a time in which rival states no longer paid traditional respects of tutelage to the Zhou Dynasty figurehead monarchs and each vied for power and total conquest. However, a great deal of diplomacy in establishing allies, bartering land, and signing peace treaties was necessary for each warring state.

After the devastating An Shi Rebellion from 755 to 763, the Tang Dynasty was in no position to reconquer Central Asia and the Tarim Basin. After several conflicts with the Tibetan Empire spanning several different decades, the Tang finally made a truce and signed a peace treaty with them in 841.

In the 11th century during the Song Dynasty (960–1279), there were cunning ambassadors such as Shen Kuo and Su Song who achieved diplomatic success with the Liao Dynasty, the often hostile Khitan neighbor to the north. Both diplomats secured the rightful borders of the Song Dynasty through knowledge of cartography and dredging up old court archives. There was also a triad of warfare and diplomacy between these two states and the Tangut Western Xia Dynasty to the northwest of Song China (centered in modern-day Shaanxi).

Long before the Tang and Song dynasties, the Chinese had sent envoys into Central Asia, India, and Persia starting with Zhang Qian in the 2nd century BC. Another notable event in Chinese diplomacy was the Chinese embassy mission of Zhou Daguan to the Khmer Empire of Cambodia in the 13th century. Chinese diplomacy was a necessity in the distinctive period of Chinese exploration. Since the Tang Dynasty (618-907 AD), the Chinese also became heavily invested in sending diplomatic envoys abroad on maritime missions into the Indian Ocean, to India, Persia, Arabia, East Africa, and Egypt. Chinese maritime activity was increased dramatically during the commercialized period of the Song Dynasty, with new nautical technologies, many more private ship owners, and an increasing amount of economic investors in overseas ventures.

During the Mongol Empire (1206-1294) the Mongols created something similar to today's diplomatic passport called paiza. The paiza were in three different types (golden, silver, and copper) depending on the envoy's level of importance. With the paiza, there came authority that the envoy can ask for food, transport, place to stay from any city, village, or clan within the empire with no difficulties.

Since the 17th century, there was a series of treaties upheld by Qing Dynasty China and Czarist Russia, beginning with the Treaty of Nerchinsk in the year 1689. This was followed up by the Aigun Treaty and the Convention of Peking in the mid 19th century.

As European power spread around the world in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries so too did its diplomatic model and system become adopted by Asian countries.

Prominent diplomatic historians

- Henry Brooks Adams, (1838–1918), US 1800–1816

- Henry Adams, U.S.

- Charles A. Beard, (1874–1948), revisionist history of coming of World War II

- Michael Beschloss, (born 1955) World War II; Cold War

- Samuel Flagg Bemis, U.S.

- Charles Howard Carter (1927–1990), Western Europe 1590–1635

- Winston Churchill, World War I; World War II

- Gordon A. Craig, (1913–2005) Germany

- Robert Dallek, 1930s to 1960s U.S.

- Jean-Baptiste Duroselle (1917–1994), 20th century Europe

- Herbert Feis (1893 – 1972), World War II; International trade

- Orlando Figes, (born 1957), Russian

- John Lewis Gaddis, Cold War

- Lloyd Gardner, 20th century U.S.

- Felix Gilbert, Renaissance

- George Peabody Gooch, (1873–1968), English historian of Modern Diplomacy

- Andreas Hillgruber, 20c Germany

- Akira Iriye (b. 1934) U.S. - Japan

- George F. Kennan, Russia

- Paul Kennedy, 19th and 20th century

- Henry Kissinger, (1923–2023); Nineteenth and twentieth century

- Walter LaFeber, 20th century U.S.

- William L. Langer, (1896–1977), US historian, World and diplomatic history

- John Lukacs, World War II

- Thomas J. McCormick, U.S.

- Walter A. McDougall, U.S. and European diplomatic history.

- Margaret MacMillan 20th century

- Charles S. Maier, 20th-century Europe

- William McNeill, world history

- Garrett Mattingly, Early modern Europe

- Arno J. Mayer, World War I

- Lewis Bernstein Namier, coming of World War II

- Geoffrey Parker, (born 1943) early modern

- Bradford Perkins, (1925–2008) Anglo-American relationships

- Leopold von Ranke, (1795–1886), European

- Pierre Renouvin, (1893–1974), 1815 to 1945

- Paul W. Schroeder, modern Europe

- Jean Edward Smith, Cold War

- Justin Harvey Smith, Mexican–American War

- Hew Strachan, World War I

- David Tal (historian), Israel

- A.J.P. Taylor, (1906–1990), Modern Europe, World Wars

- Harold Temperley, (1879–1939), British

- Arnold J. Toynbee, (1889–1975), 20th century

- Voltaire, (1694–1778), European

- Charles Webster, (1886–1961) British

- Gerhard Weinberg, World War Two, Germany

- John Wheeler-Bennett, British and German

- William Appleman Williams, American

- Randall Woods, 20th century U.S.

- Ernest Llewellyn Woodward, (1890–1971), British

- Karl W. Schweizer (1946-)18th century Britain/Europe

- Sergio Romano (writer) (1929), Italy and Russia

See also

In Spanish: Historia de la diplomacia para niños

In Spanish: Historia de la diplomacia para niños

- British foreign policy in the Middle East

- Byzantine diplomacy

- Cold War

- Diplomacy

- Diplomatic history of Australia

- Diplomatic history of World War I

- Diplomatic history of World War II

- Eastern Question, regarding Eastern Europe and Middle East

- Foreign relations of imperial China

- Historiography of the Cold War

- Historiography of the Ottoman Empire

- Historiography of World War II

- History of espionage

- History of French foreign relations

- History of German foreign policy

- History of Japanese foreign relations

- Foreign policy of the Russian Empire

- History of the foreign relations of the United Kingdom

- History of U.S. foreign policy

- Office of the Historian of the U.S. Department of State

- Society for Historians of American Foreign Relations

- International relations 1648-1814

- International relations of the Great Powers (1814–1919)

- International relations (1919–1939)

- International relations since 1989

- Military history

- United States foreign policy in the Middle East

Timelines

- Timeline of British diplomatic history

- Timeline of United States diplomatic history