Dinosaur brains and intelligence facts for kids

Dinosaur brains and intelligence are interesting topics. Dinosaurs were once regarded as stupid animals, but it is now realised that some of the smaller carnivores had above average intelligence for reptiles. This idea led to exaggerated portrayals in films like Jurassic Park.

Contents

Stegosaurus

The idea that Stegosaurus had a "brain the size of a walnut" (an oft-repeated phrase), was not quite accurate. It had a brain the size of a dog's, but in proportion to its body, the brain was very small. In the 1880s a well-preserved Stegosaurus braincase allowed Othniel Charles Marsh to get a cast of the brain cavity, which gave an idea of the brain size. The endocast showed that the brain was indeed small: relative to body size, maybe the smallest among the dinosaurs. The fact that an animal weighing over 4.5 metric tonnes (5 short tons) could have a brain of no more than 80 grams (2.8 oz) led to the idea that dinosaurs were unintelligent, an idea now largely rejected.

Marsh also noted a large canal in the hip region of the spinal cord, which could have accommodated a structure up to 20 times larger than the famously small brain. This may have been used to coordinate the hind region in defence against theropod attack. This function for the "second brain" is not proved by any direct evidence.

Brain-body size relationship

Brain size usually increases with body size in animals (is positively correlated). That means large animals usually have larger brains than smaller animals. The relationship is not linear however. Generally, small mammals have relatively larger brains than big ones. Mice have a direct brain/body size ratio similar to humans (1/40), while elephants have comparatively small brain/body size (1/560), though elephants are obviously quite intelligent animals.

Encephalization quotient (EQ)

The formula for the curve varies, but is usually given as Ew(brain) = 0.12w(body)2/3. As this formula is based on data from mammals, it should be applied to other animals with caution. For some of the other vertebrate classes the power of 3/4 rather than 2/3 is sometimes used, and for many groups of invertebrates the formula may give no meaningful results at all.

Intelligence

Intelligence in animals is hard to establish, but the larger the brain is relative to the body, the more brain weight might be available for complex cognitive tasks. Rather than simply measuring raw brain weight, the EQ formula makes for a ranking of animals. The ranking coincides better with the observed complexity of behaviour. Mean EQ for mammals is around 1, with carnivorans, cetaceans and primates above 1, and insectivores and herbivores below. It also puts humans at the top of the list. The relationship between brain-to-body mass ratio and complexity of behaviour is not perfect, because other factors also influence intelligence. These factors include the evolution of the recent cerebral cortex and different degrees of brain folding. This increase the surface of the cortex, which is positively correlated to intelligence in humans.

Dinosaur brains

Problems with EQ

Traditional comparisons of brain volume to body mass in dinosaurs have estimated brain size as the volume of the endocast. However, the brain of the modern reptile genus Sphenodon fills only about half of its endocranial volume. Some paleontologists used this fifty percent estimate in their estimates of dinosaur brain volume. Other workers have observed that details on the endocranial surface indicates that some fossil reptiles had brains that occupied a much larger portion of the endocranium. Larsson notes that the transition from reptiles to birds prevents using a set ratio from being a valid approach to estimating the volume of the endocranium occupied by a dinosaur's brain.

Adding difficulty is the wide range of estimates for live mass. One study estimated that the live masses for many dinosaur genera had a four-fold range. Larsson laments that "[t]he broad ranges of body mass estimates, combined with the ambiguous ratio of endocranial volume occupied by the brain, present a high degree of uncertainty for [creating an] index of brain size". Consequently, he attempted to minimize errors by making a different kind of comparison.

While it is difficult to estimate the absolute volume of the brain, the proportions of its various regions of the brain should be the same in the endocast as it was in the live brain. Larsson's study compared the ratio of the cerebrum, which is clearly marked on the inside of skulls, to the rest of the endocast's volume. According to Larsson, his technique is superior to traditional comparisons of brain volume to estimated live body mass.

Theropod brains

Most dinosaurs, and most theropods, had brains no better than present-day reptiles, so far as can be estimated. In a 2001 study of a Carcharodontosaurus saharicus endocast, Hans Larsson found that both C. saharicus and Allosaurus had a ratio of cerebrum to brain volume that was very similar to non-avian reptiles. By contrast, the Tyrannosaurus ratio was slightly in the direction of a more bird-like proportion. Since tyrannosaurs are relatively basal coelurosaurs, this is evidence that the advent of the Coelurosauria marks the beginning of a trend in theropod brain enlargement.

Troodon

Troodon's cerebrum-to-brain-volume ratio was 31.5% to 63% of the way from a nonavian reptile proportion to a truly avian one.

Archaeopteryx

Archaeopteryx had a cerebrum-to-brain-volume ratio 78% of the way to modern birds.

Summary

The method used for Larsson's comparison was not the EQ, but a ratio of the size of the cerebrum to the whole brain. The cerebrum is chiefly responsible for what might be called 'intelligent behaviour'.

The brains of dinosaurs were generally much like other reptiles in their proportions. The exception is the coelurosaurs, which had cerebra proportionately larger than most reptiles, but proportionately smaller than modern birds.

Images for kids

-

Birds are avian dinosaurs, and in phylogenetic taxonomy are included in the group Dinosauria.

-

Sir Richard Owen's coining of the word dinosaur, at a meeting of the British Association for the Advancement of Science in 1841

-

Paleontologist Robert T. Bakker with mounted skeleton of a tyrannosaurid (Gorgosaurus libratus)

-

Scipionyx fossil with intestines, Natural History Museum of Milan

-

The early dinosaurs Herrerasaurus (large), Eoraptor (small) and a Plateosaurus skull, from the Triassic

-

Restoration of six dromaeosaurid theropods: from left to right Microraptor, Velociraptor, Austroraptor, Dromaeosaurus, Utahraptor, and Deinonychus

-

Restoration of four macronarian sauropods: from left to right Camarasaurus, Brachiosaurus, Giraffatitan, and Euhelopus

-

Restoration of six ornithopods; far left: Camptosaurus, left: Iguanodon, center background: Shantungosaurus, center foreground: Dryosaurus, right: Corythosaurus, far right (large) Tenontosaurus.

-

An adult bee hummingbird, the smallest known dinosaur

-

A nesting ground of the hadrosaur Maiasaura peeblesorum was discovered in 1978

-

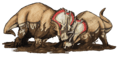

Restoration of two Centrosaurus apertus engaged in intra-specific combat

-

Restoration of a striking and unusual visual display in a Lambeosaurus magnicristatus

-

Nest of a plover (Charadrius)

-

Fossil interpreted as a nesting oviraptorid Citipati at the American Museum of Natural History. Smaller fossil far right showing inside one of the eggs.

-

This 1897 restoration of Brontosaurus as an aquatic, tail-dragging animal, by Charles R. Knight, typified early views on dinosaur lifestyles.

-

Various feathered non-avian dinosaurs, including Archaeopteryx, Anchiornis, Microraptor and Zhenyuanlong

-

The Chicxulub Crater at the tip of the Yucatán Peninsula; the impactor that formed this crater may have caused the dinosaur extinction.

-

The battles that may have occurred between Tyrannosaurus and Triceratops are a recurring theme in popular science and dinosaurs' depiction in culture

See also

In Spanish: Dinosaurios para niños

In Spanish: Dinosaurios para niños