Brooklyn Bridge facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Brooklyn Bridge |

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Coordinates | 40°42′21″N 73°59′47″W / 40.7057°N 73.9964°W |

| Carries | 5 lanes of roadway Elevated trains (until 1944) Streetcars (until 1950) Pedestrians and bicycles |

| Crosses | East River |

| Locale | New York City (Civic Center, Manhattan – Dumbo/Brooklyn Heights, Brooklyn) |

| Maintained by | New York City Department of Transportation |

| ID number | 22400119 |

| Characteristics | |

| Design | Suspension/Cable-stay hybrid |

| Total length | 6,016 ft (1,833.7 m; 1.1 mi) |

| Width | 85 ft (25.9 m) |

| Height | 272 ft (82.9 m) (towers) |

| Longest span | 1,595.5 ft (486.3 m) |

| Clearance below | 127 ft (38.7 m) above mean high water |

| History | |

| Designer | John Augustus Roebling |

| Constructed by | New York Bridge Company |

| Opened | May 24, 1883 |

| Statistics | |

| Daily traffic | 121,930 (2019) |

| Toll | Free (Manhattan-bound to FDR Drive, and Brooklyn-bound) Variable congestion charge (Manhattan-bound to all other exits) |

|

Brooklyn Bridge

|

|

| Built | 1869–1883 |

| Architectural style | Gothic Revival |

| NRHP reference No. | 66000523 |

| Significant dates | |

| Added to NRHP | October 15, 1966 |

| Designated NHL | January 29, 1964 |

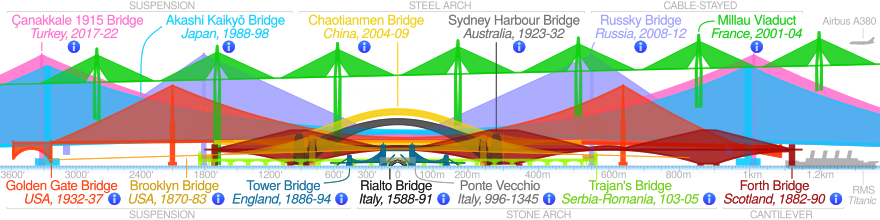

The Brooklyn Bridge is a hybrid cable-stayed/suspension bridge in New York City, spanning the East River between the boroughs of Manhattan and Brooklyn. Opened on May 24, 1883, the Brooklyn Bridge was the first fixed crossing of the East River. It was also the longest suspension bridge in the world at the time of its opening, with a main span of 1,595.5 feet (486.3 m) and a deck 127 ft (38.7 m) above Mean High Water. The span was originally called the New York and Brooklyn Bridge or the East River Bridge but was officially renamed the Brooklyn Bridge in 1915.

The Brooklyn Bridge is the southernmost of four vehicular bridges directly connecting Manhattan Island and Long Island, with the Manhattan Bridge, the Williamsburg Bridge, and the Queensboro Bridge to the north. Only passenger vehicles and pedestrian and bicycle traffic are permitted. A major tourist attraction since its opening, the Brooklyn Bridge has become an icon of New York City. The Brooklyn Bridge is designated a National Historic Landmark, a New York City landmark, and a National Historic Civil Engineering Landmark.

Description

The Brooklyn Bridge, an early example of a steel-wire suspension bridge, uses a hybrid cable-stayed/suspension bridge design, with both vertical and diagonal suspender cables. Its stone towers are neo-Gothic, with characteristic pointed arches. The New York City Department of Transportation (NYCDOT), which maintains the bridge, says that its original paint scheme was "Brooklyn Bridge Tan" and "Silver", but other accounts state that it was originally entirely "Rawlins Red".

Deck

To provide sufficient clearance for shipping in the East River, the Brooklyn Bridge incorporates long approach viaducts on either end to raise it from low ground on both shores. Including approaches, the Brooklyn Bridge is a total of 6,016 feet (1,834 m) long when measured between the curbs at Park Row in Manhattan and Sands Street in Brooklyn. A separate measurement of 5,989 feet (1,825 m) is sometimes given; this is the distance from the curb at Centre Street in Manhattan.

Suspension span

The main span between the two suspension towers is 1,595.5 feet (486.3 m) long and 85 feet (26 m) wide. The bridge "elongates and contracts between the extremes of temperature from 14 to 16 inches". Navigational clearance is 127 ft (38.7 m) above Mean High Water (MHW). A 1909 Engineering Magazine article said that, at the center of the span, the height above MHW could fluctuate by more than 9 feet (2.7 m) due to temperature and traffic loads, while more rigid spans had a lower maximum deflection.

The side spans, between each suspension tower and each side's suspension anchorages, are 930 feet (280 m) long. At the time of construction, engineers had not yet discovered the aerodynamics of bridge construction, and bridge designs were not tested in wind tunnels. John Roebling designed the Brooklyn Bridge's truss system to be six to eight times as strong as he thought it needed to be. As such, the open truss structure supporting the deck is, by its nature, subject to fewer aerodynamic problems. However, due to a supplier's fraudulent substitution of inferior-quality wire in the initial construction, the bridge was reappraised at the time as being only four times as strong as necessary.

The main span and side spans are supported by a structure containing trusses that run parallel to the roadway, each of which is 33 feet (10 m) deep. Originally there were six trusses, but two were removed during a late-1940s renovation. The trusses allow the Brooklyn Bridge to hold a total load of 18,700 short tons (17,000 metric tons), a design consideration from when it originally carried heavier elevated trains. These trusses are held up by suspender ropes, which hang downward from each of the four main cables. Crossbeams run between the trusses at the top, and diagonal and vertical stiffening beams run on the outside and inside of each roadway.

An elevated pedestrian-only promenade runs in between the two roadways and 18 feet (5.5 m) above them. It typically runs 4 feet (1.2 m) below the level of the crossbeams, except at the areas surrounding each tower. Here, the promenade rises to just above the level of the crossbeams, connecting to a balcony that slightly overhangs the two roadways. The path is generally 10 to 17 feet (3.0 to 5.2 m) wide. The iron railings were produced by Janes & Kirtland, a Bronx iron foundry that also made the United States Capitol dome and the Bow Bridge in Central Park.

Approaches

Each of the side spans is reached by an approach ramp. The 971-foot (296 m) approach ramp from the Brooklyn side is shorter than the 1,567-foot (478 m) approach ramp from the Manhattan side. The approaches are supported by Renaissance-style arches made of masonry; the arch openings themselves were filled with brick walls, with small windows within. The approach ramp contains nine arch or iron-girder bridges across side streets in Manhattan and Brooklyn.

Underneath the Manhattan approach, a series of brick slopes or "banks" was developed into a skate park, the Brooklyn Banks, in the late 1980s. The park uses the approach's support pillars as obstacles. In the mid-2010s, the Brooklyn Banks were closed to the public because the area was being used as a storage site during the bridge's renovation. The skateboarding community has attempted to save the banks on multiple occasions; after the city destroyed the smaller banks in the 2000s, the city government agreed to keep the larger banks for skateboarding. When the NYCDOT removed the bricks from the banks in 2020, skateboarders started an online petition. In the 2020s, local resident Rosa Chang advocated for the 9-acre (3.6 ha) space under the Manhattan approach to be converted into a recreational area known as Gotham Park. Some of the space under the Manhattan approach reopened in May 2023 as a park called the Arches; this was followed in November 2024 by another 15,000-square-foot (1,400 m2) section of parkland.

Cables

The Brooklyn Bridge contains four main cables, which descend from the tops of the suspension towers and help support the deck. Two are located to the outside of the bridge's roadways, while two are in the median of the roadways. Each main cable measures 15.75 inches (40.0 cm) in diameter and contains 5,282 parallel, galvanized steel wires wrapped closely together in a cylindrical shape. These wires are bundled in 19 individual strands, with 278 wires to a strand. This was the first use of bundling in a suspension bridge and took several months for workers to tie together. Since the 2000s, the main cables have also supported a series of 24-watt LED lighting fixtures, referred to as "necklace lights" due to their shape.

In addition, either 1,088, 1,096, or 1,520 galvanized steel wire suspender cables hang downward from the main cables. Another 400 cable stays extend diagonally from the towers. The vertical suspender cables and diagonal cable stays hold up the truss structure around the bridge deck. The bridge's suspenders originally used wire rope, which was replaced in the 1980s with galvanized steel made by Bethlehem Steel. The vertical suspender cables measure 8 to 130 feet (2.4 to 39.6 m) long, and the diagonal stays measure 138 to 449 feet (42 to 137 m) long.

Anchorages

Each side of the bridge contains an anchorage for the main cables. The anchorages are trapezoidal limestone structures located slightly inland of the shore, measuring 129 by 119 feet (39 by 36 m) at the base and 117 by 104 feet (36 by 32 m) at the top. Each anchorage weighs 60,000 short tons (54,000 long tons; 54,000 t). The Manhattan anchorage rests on a foundation of bedrock while the Brooklyn anchorage rests on clay.

The anchorages both have four anchor plates, one for each of the main cables, which are located near ground level and parallel to the ground. The anchor plates measure 16 by 17.5 feet (4.9 by 5.3 m), with a thickness of 2.5 feet (0.76 m) and weigh 46,000 pounds (21,000 kg) each. Each anchor plate is connected to the respective main cable by two sets of nine eyebars, each of which is about 12.5 feet (3.8 m) long and up to 9 by 3 inches (229 by 76 mm) thick. The chains of eyebars curve downward from the cables toward the anchor plates, and the eyebars vary in size depending on their position.

The anchorages also contain numerous passageways and compartments. Starting in 1876, in order to fund the bridge's maintenance, the New York City government made the large vaults under the bridge's Manhattan anchorage available for rent, and they were in constant use during the early 20th century. The vaults were used to store wine, as they were kept at a consistent 60 °F (16 °C) temperature due to a lack of air circulation. The Manhattan vault was called the "Blue Grotto" because of a shrine to the Virgin Mary next to an opening at the entrance. The vaults were closed for public use in the late 1910s and 1920s during World War I and Prohibition but were reopened thereafter. When New York magazine visited one of the cellars in 1978, it discovered a "fading inscription" on a wall reading: "Who loveth not wine, women and song, he remaineth a fool his whole life long." Leaks found within the vault's spaces necessitated repairs during the late 1980s and early 1990s. By the late 1990s, the chambers were being used to store maintenance equipment.

Towers

The bridge's two suspension towers are 278 feet (85 m) tall with a footprint of 140 by 59 feet (43 by 18 m) at the high water line. They are built of limestone, granite, and Rosendale cement. The limestone was quarried at the Clark Quarry in Essex County, New York. The granite blocks were quarried and shaped on Vinalhaven Island, Maine, under a contract with the Bodwell Granite Company, and delivered from Maine to New York by schooner. The Manhattan tower contains 46,945 cubic yards (35,892 m3) of masonry, while the Brooklyn tower has 38,214 cubic yards (29,217 m3) of masonry. There are 56 LED lamps mounted onto the towers.

Each tower contains a pair of Gothic Revival pointed arches, through which the roadways run. The arch openings are 117 feet (36 m) tall and 33.75 feet (10.29 m) wide. The tops of the towers are located 159 feet (48 m) above the floor of each arch opening, while the floors of the openings are 119.25 feet (36.35 m) above mean water level, giving the towers a total height of 278.25 feet (84.81 m) above mean high water.

Caissons

The towers rest on underwater caissons made of southern yellow pine and filled with cement. Inside both caissons were spaces for construction workers. The Manhattan side's caisson is slightly larger, measuring 172 by 102 feet (52 by 31 m) and located 78.5 feet (23.9 m) below high water, while the Brooklyn side's caisson measures 168 by 102 feet (51 by 31 m) and is located 44.5 feet (13.6 m) below high water. The caissons were designed to hold at least the weight of the towers which would exert a pressure of 5 short tons per square foot (49 t/m2) when fully built, but the caissons were over-engineered for safety. During an accident on the Brooklyn side, when air pressure was lost and the partially-built towers dropped full-force down, the caisson sustained an estimated pressure of 23 short tons per square foot (220 t/m2) with only minor damage. Most of the timber used in the bridge's construction, including in the caissons, came from mills at Gascoigne Bluff on St. Simons Island, Georgia.

The Brooklyn side's caisson, which was built first, originally had a height of 9.5 feet (2.9 m) and a ceiling composed of five layers of timber, each layer 1 foot (0.30 m) tall. Ten more layers of timber were later added atop the ceiling, and the entire caisson was wrapped in tin and wood for further protection against flooding. The thickness of the caisson's sides was 8 feet (2.4 m) at both the bottom and the top. The caisson had six chambers: two each for dredging, supply shafts, and airlocks.

The caisson on the Manhattan side was slightly different because it had to be installed at a greater depth. To protect against the increased air pressure at that depth, the Manhattan caisson had 22 layers of timber on its roof, seven more than its Brooklyn counterpart had. The Manhattan caisson also had fifty 4-inch-diameter (10 cm) pipes for sand removal, a fireproof iron-boilerplate interior, and different airlocks and communication systems.

Usage

Vehicular traffic

Horse-drawn carriages have been allowed to use the Brooklyn Bridge's roadways since its opening. Originally, each of the two roadways carried two lanes of a different direction of traffic. The lanes were relatively narrow at only 8 feet (2.4 m) wide. In July 1922, motor vehicles were banned from the bridge; the ban lasted until May 1925.

After 1950, the main roadway carried six lanes of automobile traffic, three in each direction. It was then reduced to five lanes with the addition of a two-way bike lane on the Manhattan-bound side in 2021. Because of the roadway's posted height restriction of 11 ft (3.4 m) and weight restriction of 6,000 lb (2,700 kg), commercial vehicles and buses are prohibited from using the Brooklyn Bridge. The weight restrictions prohibit heavy passenger vehicles such as pickup trucks and SUVs from using the bridge, though this is not often enforced in practice.

On the Brooklyn side, vehicles can enter the bridge from Tillary/Adams Streets to the south, Sands/Pearl Streets to the west, and exit 28B of the eastbound Brooklyn-Queens Expressway. In Manhattan, cars can enter from both the northbound and southbound FDR Drive, as well as Park Row to the west, Chambers/Centre Streets to the north, and Pearl Street to the south. However, the exit from the bridge to northbound Park Row was closed after the September 11 attacks because of increased security concerns: that section of Park Row ran under One Police Plaza, the NYPD headquarters.

Exit list

Vehicular access to the bridge is provided by a complex series of ramps on both sides of the bridge. There are two entrances to the bridge's pedestrian promenade on either side. The current configuration was constructed from the mid-1950s up until the early 1970s. After 9/11, the ramp onto Park Row was restricted to public traffic, there are no plans to reopen it.

| County | Location | Mile | Roads intersected | Notes | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brooklyn | Brooklyn Heights | 0.0 | 0.0 | Tillary Street / Adams Street south | Pedestrian and bicycle path |

| 0.4 | 0.64 | Northbound entrance only; I-278 exit 28B | |||

| Southbound exit only; access to I-278 via Old Fulton/Prospect Streets | |||||

| East River | 0.7– 1.0 |

1.1– 1.6 |

Suspension span | ||

| Manhattan | Financial District | 1.2 | 1.9 | Park Row north | Northbound exit only; closed to regular traffic since the September 11 terrorist attacks |

| 1.3 | 2.1 | Northbound exit and southbound entrance; FDR Drive exit 2 | |||

| 1.4 | 2.3 | Park Row south | Northbound exit and southbound entrance; pedestrian staircase | ||

| 1.5 | 2.4 | Pedestrian and bicycle path | |||

| 1.000 mi = 1.609 km; 1.000 km = 0.621 mi | |||||

Rail traffic

Formerly, rail traffic operated on the Brooklyn Bridge as well. Cable cars and elevated railroads used the bridge until 1944, while trolleys ran until 1950.

Cable cars and elevated railroads

The New York and Brooklyn Bridge Railway, a cable car service, began operating on September 25, 1883; it ran on the inner lanes of the bridge, between terminals at the Manhattan and Brooklyn ends. Since Washington Roebling believed that steam locomotives would put excessive loads upon the structure of the Brooklyn Bridge, the cable car line was designed as a steam/cable-hauled hybrid. They were powered from a generating station under the Brooklyn approach. The cable cars could not only regulate their speed on the 3+3⁄4% upward and downward approaches, but also maintain a constant interval between each other. There were 24 cable cars in total.

Initially, the service ran with single-car trains, but patronage soon grew so much that by October 1883, two-car trains were in use. The line carried three million people in the first six months, nine million in 1884, and nearly 20 million in 1885 following the opening of the Brooklyn Union Elevated Railroad. Accordingly, the track layout was rearranged and more trains were ordered. At the same time, there were highly controversial plans to extend the elevated railroads onto the Brooklyn Bridge, under the pretext of extending the bridge itself. After disputes, the trustees agreed to build two elevated routes to the bridge on the Brooklyn side. Patronage continued to increase, and in 1888, the tracks were lengthened and even more cars were constructed to allow for four-car cable car trains. Electric wires for the trolleys were added by 1895, allowing for the potential future decommissioning of the steam/cable system. The terminals were rebuilt once more in July 1895, and, following the implementation of new electric cars in late 1896, the steam engines were dismantled and sold.

Following the unification of the cities of New York and Brooklyn in 1898, the New York and Brooklyn Bridge Railway ceased to be a separate entity that June and the Brooklyn Rapid Transit Company (BRT) assumed control of the line. The BRT started running through-services of elevated trains, which ran from Park Row Terminal in Manhattan to points in Brooklyn via the Sands Street station on the Brooklyn side. Before reaching Sands Street (at Tillary Street for Fulton Street Line trains, and at Bridge Street for Fifth Avenue Line and Myrtle Avenue Line trains), elevated trains bound for Manhattan were uncoupled from their steam locomotives. The elevated trains were then coupled to the cable cars, which would pull the passenger carriages across the bridge.

The BRT did not run any elevated train through services from 1899 to 1901. Due to increased patronage after the opening of the Interborough Rapid Transit Company (IRT)'s first subway line, the Park Row station was rebuilt in 1906. In the early 20th century, there were plans for Brooklyn Bridge elevated trains to run underground to the BRT's proposed Chambers Street station in Manhattan, though the connection was never opened. The overpass across William Street was closed in 1913 to make way for the proposed connection. In 1929, the overpass was reopened after it became clear that the connection would not be built.

After the IRT's Joralemon Street Tunnel and the Williamsburg Bridge tracks opened in 1908, the Brooklyn Bridge no longer held a monopoly on rail service between Manhattan and Brooklyn, and cable service ceased. New subway lines from the IRT and from the BRT's successor Brooklyn–Manhattan Transit Corporation (BMT), built in the 1910s and 1920s, posed significant competition to the Brooklyn Bridge rail services. With the opening of the Independent Subway System in 1932 and the subsequent unification of all three companies into a single entity in 1940, the elevated services started to decline, and the Park Row and Sands Street stations were greatly reduced in size. The Fifth Avenue and Fulton Street services across the Brooklyn Bridge were discontinued in 1940 and 1941 respectively, and the elevated tracks were abandoned permanently with the withdrawal of Myrtle Avenue services in 1944.

Trolleys

A plan for trolley service across the Brooklyn Bridge was presented in 1895. Two years later, the Brooklyn Bridge trustees agreed to a plan where trolleys could run across the bridge under ten-year contracts. Trolley service, which began in 1898, ran on what are now the two middle lanes of each roadway (shared with other traffic). When cable service was withdrawn in 1908, the trolley tracks on the Brooklyn side were rebuilt to alleviate congestion. Trolley service on the middle lanes continued until the elevated lines stopped using the bridge in 1944, when they moved to the protected center tracks. On March 5, 1950, the streetcars also stopped running, and the bridge was redesigned exclusively for automobile traffic.

Walkway

The Brooklyn Bridge has an elevated promenade open to pedestrians in the center of the bridge, located 18 feet (5.5 m) above the automobile lanes. The promenade is usually located 4 feet (1.2 m) below the height of the girders, except at the approach ramps leading to each tower's balcony. The path is generally 10 to 17 feet (3.0 to 5.2 m) wide, though this is constrained by obstacles such as protruding cables, benches, and stairways, which create "pinch points" at certain locations. The path narrows to 10 feet (3.0 m) at the locations where the main cables descend to the level of the promenade. Further exacerbating the situation, these "pinch points" are some of the most popular places to take pictures. As a result, in 2016, the NYCDOT announced that it planned to double the promenade's width.

A center line was painted to separate cyclists from pedestrians in 1971, creating one of the city's first dedicated bike lanes. Initially, the northern side of the promenade was used by pedestrians and the southern side by cyclists. In 2000, these were swapped, with cyclists taking the northern side and pedestrians taking the southern side. On September 14, 2021, the DOT closed off the inner-most car lane on the Manhattan-bound side with protective barriers and fencing to create a new bike path. Cyclists are now prohibited from the upper pedestrian lane.

Pedestrian access to the bridge from the Brooklyn side is from either the median of Adams Street at its intersection with Tillary Street or a staircase near Prospect Street between Cadman Plaza East and West. In Manhattan, the pedestrian walkway is accessible from crosswalks at the intersection of the bridge and Centre Street, or through a staircase leading to Park Row.

Emergency use

While the bridge has always permitted the passage of pedestrians, the promenade facilitates movement when other means of crossing the East River have become unavailable. During transit strikes by the Transport Workers Union in 1980 and 2005, people commuting to work used the bridge; they were joined by Mayors Ed Koch and Michael Bloomberg, who crossed as a gesture to the affected public. Pedestrians also walked across the bridge as an alternative to suspended subway services following the 1965, 1977, and 2003 blackouts, and after the September 11 attacks.

During the 2003 blackouts, many crossing the bridge reported a swaying motion. The higher-than-usual pedestrian load caused this swaying, which was amplified by the tendency of pedestrians to synchronize their footfalls with a sway. Several engineers expressed concern about how this would affect the bridge, although others noted that the bridge did withstand the event and that the redundancies in its design—the inclusion of the three support systems (suspension system, diagonal stay system, and stiffening truss)—make it "probably the best secured bridge against such movements going out of control". In designing the bridge, John Roebling had stated that the bridge would sag but not fall, even if one of these structural systems were to fail altogether.

Historical designations and plaques

The Brooklyn Bridge has been listed as a National Historic Landmark since January 29, 1964, and was subsequently added to the National Register of Historic Places on October 15, 1966. The bridge has also been a New York City designated landmark since August 24, 1967, and was designated a National Historic Civil Engineering Landmark in 1972. In addition, it was placed on UNESCO's list of tentative World Heritage Sites in 2017.

A bronze plaque is attached to the Manhattan anchorage, which was constructed on the site of the Samuel Osgood House at 1 Cherry Street in Manhattan. Named after Samuel Osgood, a Massachusetts politician and lawyer, it was built in 1770 and served as the first U.S. presidential mansion. The Osgood House was demolished in 1856.

Another plaque on the Manhattan side of the pedestrian promenade, installed by the city in 1975, indicates the bridge's status as a city landmark.

Culture

The Brooklyn Bridge has had an impact on idiomatic American English. For example, references to "selling the Brooklyn Bridge" are frequent in American culture, sometimes presented as a historical reality but more often as an expression meaning an idea that strains credulity. George C. Parker and William McCloundy were two early 20th-century con men who may have perpetrated this scam successfully, particularly on new immigrants, although the author of The Brooklyn Bridge: A Cultural History wrote, "No evidence exists that the bridge has ever been sold to a 'gullible outlander'".

As a tourist attraction, the Brooklyn Bridge is a popular site for clusters of love locks, wherein a couple inscribes a date and their initials onto a lock, attach it to the bridge, and throw the key into the water as a sign of their love. The practice is illegal in New York City and the NYPD can give violators a $100 fine. NYCDOT workers periodically remove the love locks from the bridge at a cost of $100,000 per year.

To highlight the Brooklyn Bridge's cultural status, the city proposed building a Brooklyn Bridge museum near the bridge's Brooklyn end in the 1970s. Though the museum was ultimately not constructed, as many as 10,000 drawings and documents relating to it were found in a carpenter shop in Williamsburg in 1976. These documents were given to the New York City Municipal Archives, where they are normally located, though a selection of them were displayed at the Whitney Museum of American Art when they were discovered.

Media

The bridge is often featured in wide shots of the New York City skyline in television and film and has been depicted in numerous works of art. Fictional works have used the Brooklyn Bridge as a setting; for instance, the dedication of a portion of the bridge, and the bridge itself, were key components in the 2001 film Kate & Leopold. Furthermore, the Brooklyn Bridge has also served as an icon of America, with mentions in numerous songs, books, and poems. Among the most notable of these works is that of American Modernist poet Hart Crane, who used the Brooklyn Bridge as a central metaphor and organizing structure for his second book of poetry, The Bridge (1930).

The Brooklyn Bridge has also been lauded for its architecture. One of the first positive reviews was "The Bridge As A Monument", a Harper's Weekly piece written by architecture critic Montgomery Schuyler and published a week after the bridge's opening. In the piece, Schuyler wrote: "It so happens that the work which is likely to be our most durable monument, and to convey some knowledge of us to the most remote posterity, is a work of bare utility; not a shrine, not a fortress, not a palace, but a bridge." Architecture critic Lewis Mumford cited the piece as the impetus for serious architectural criticism in the U.S. He wrote that in the 1920s the bridge was a source of "joy and inspiration" in his childhood, and that it was a profound influence in his adolescence. Later critics would regard the Brooklyn Bridge as a work of art, as opposed to an engineering feat or a means of transport. Not all critics appreciated the bridge, however. Henry James, writing in the early 20th century, cited the bridge as an ominous symbol of the city's transformation into a "steel-souled machine room".

The construction of the Brooklyn Bridge is detailed in numerous media sources, including David McCullough's 1972 book The Great Bridge and Ken Burns's 1981 documentary Brooklyn Bridge. It is also described in Seven Wonders of the Industrial World, a BBC docudrama series with an accompanying book, as well as Chief Engineer: Washington Roebling, The Man Who Built the Brooklyn Bridge, a biography published in 2017.

See also

In Spanish: Puente de Brooklyn para niños

In Spanish: Puente de Brooklyn para niños

- Brooklyn Bridge Park

- Brooklyn Bridge trolleys

- List of bridges and tunnels in New York City

- List of bridges and tunnels on the National Register of Historic Places in New York

- List of bridges documented by the Historic American Engineering Record in New York

- List of National Historic Landmarks in New York City

- List of New York City Designated Landmarks in Manhattan below 14th Street

- List of New York City Designated Landmarks in Brooklyn

- List of tallest structures built before the 20th century

- National Register of Historic Places listings in Manhattan below 14th Street

- National Register of Historic Places listings in Brooklyn