Argentavis facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Argentavis |

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Reconstruction of A. magnificens | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Genus: |

Argentavis

|

| Species: |

magnificens

|

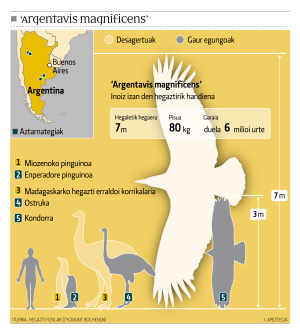

Argentavis magnificens was among the largest flying birds ever to exist. While it is still considered the heaviest flying bird of all time, Argentavis was likely surpassed in wingspan by Pelagornis sandersi which is estimated to have possessed wings some 20% longer than Argentavis and which was described in 2014. A. magnificens, sometimes called the Giant Teratorn, is an extinct species known from three sites in the Epecuén and Andalhualá Formations in central and northwestern Argentina dating to the Late Miocene (Huayquerian), where a good sample of fossils has been obtained.

Contents

Description

The single known humerus (upper arm bone) specimen of Argentavis is somewhat damaged. Even so, it allows a fairly accurate estimate of its length in life. Argentavis's humerus was only slightly shorter than an entire human arm. The species apparently had stout, strong legs and large feet which enabled it to walk with ease. The bill was large, rather slender, and had a hooked tip with a wide gape.

Size

Argentavis wingspan estimates varied widely depending on the method used for scaling, i.e. regression analyses or comparisons with the California condor. At one time, wingspans have been published for the species up to 7.5 to 8 m (24 ft 7 in to 26 ft 3 in) but more recent estimates put the wingspan more likely in the range of 5.09 to 6.5 m (16 ft 8 in to 21 ft 4 in). Whether this span could have reached 7 m (23 ft 0 in) appears uncertain per modern authorities. At the time of description, Argentavis was the largest winged bird known to exist but is now known to have been exceeded by another extinct species, Pelagornis sandersi, described in 2014 as having a typical wingspan of 7 to 7.4 m (23 ft 0 in to 24 ft 3 in). Argentavis had an estimated height when standing on the ground that was roughly equivalent to that of a person, at 1.5 to 1.8 m (4 ft 11 in to 5 ft 11 in), furthermore its total length (from bill tip to tail tip) was approximately 3.5 m (11 ft 6 in).

Prior published weights gave Argentavis a body mass of 80 kg (180 lb), but more refined techniques show a more typical mass would likely have been 70 to 72 kg (154 to 159 lb), although weights could have varied depending on conditions. Argentavis retains the title of the heaviest flying bird known still by a considerable margin, for example Pelagornis weighed no more than 22 to 40 kg (49 to 88 lb). For comparison, the living bird with the largest wingspan is the wandering albatross, averaging 3 m (9 ft 10 in) and spanning up to 3.7 m (12 ft 2 in). Since A. magnificens is known to have been a land bird, another good point of comparison is the Andean condor, the largest extant flighted land bird going on average wing spread and weight, with a wingspan of up to 3.3 m (10 ft 10 in) and an average wingspan of around 2.82 m (9 ft 3 in). This condor can weigh up to 15 kg (33 lb). New World vultures such as the condor are thought to be the closest living relations to Argentavis and other teratorns. Average weights are of course much less in both the albatross and condor than this teratorn, at approximately 8.5 kg (19 lb) and 11.3 kg (25 lb), respectively.

The ability to fly is not a simple question of weight ratios, except in extreme cases; size and structure of the wing must also be taken into account. As a rule of thumb, a wing loading of 25 kg/m2 is considered the limit for avian flight. The heaviest extant flying birds are known to weigh up to 21 kg (46 lb) (there are several contenders, among which are the European great bustard and the African kori bustard). An individual mute swan, which may have lost the power of flight due to extreme weight, was found to have weighed 23 kg (51 lb). Meanwhile, the sarus crane is the tallest flying bird alive, at up to 1.8 m (5 ft 11 in) tall, standing about as high as Argentavis due to its long legs and neck.

The largest flying creatures overall that are known to have existed are not birds, but instead distantly-related archosaurs, namely the azhdarchid pterosaurs of the Cretaceous. The wingspans of larger azhdarchids, such as Quetzalcoatlus and Hatzegopteryx, have been estimated to exceed 10 m (33 ft), with less conservative estimates being 12 m (39 ft) or more. Mass estimates for these azhdarchids are on the order of 200–250 kg (440–550 lb) and their estimated height on the ground was roughly analogous to an elephant or small giraffe.

Currently accepted estimates for the size of Argentavis are:

- Wingspan: 5.09–6.5 m (16 ft 8 in – 21 ft 4 in)

- Wing area: 8.11 m2 (87.3 sq ft)

- Wing loading: 84.6 N/m2 (1.77 lb/ft2)

- Body length: 3.5 m (11 ft 6 in)

- Height: 1.5 to 1.8 m (4 ft 11 in to 5 ft 11 in)

- Mass: 70 to 72 kg (154 to 159 lb)

Paleobiology

Life history

Comparison with extant birds suggests it laid one or two eggs with a mass of somewhat over 1 kg (2.2 lb) (smaller than an ostrich egg) every two years. Climate considerations make it likely that the birds incubated over the winter, mates exchanging duties of incubating and procuring food every few days, and that the young were independent after some 16 months, but not fully mature until aged about a dozen years. Mortality must have been very low; to maintain a viable population less than about 2% of birds may have died each year. Because of its large size and ability to fly, Argentavis suffered hardly any predation, and mortality was mainly from old age and disease.

Flight

From the size and structure of its wings, it is inferred that A. magnificens flew mainly by soaring, using flapping flight only during short periods. It is probable that it used thermal currents as well. It has been estimated that the minimal velocity for the wing of A. magnificens is about 11 metres per second (36 ft/s) or 40 kilometres per hour (25 mph). Especially for takeoff, it would have depended on the wind. Although its legs were strong enough to provide it with a running or jumping start, the wings were simply too long to flap effectively until the bird was some height off the ground. However, skeletal evidence suggests that its breast muscles were not powerful enough for wing flapping for extended periods. Argentavis may have used mountain slopes and headwinds to take off, and probably could manage to do so from even gently sloping terrain with little effort. It may have flown and lived much like the modern Andean condor, scanning large areas of land from aloft for carrion. The climate of the Andean foothills in Argentina during the late Miocene was warmer and drier than today, which would have further aided the bird in staying aloft atop thermal updrafts.

Studies on condor flight indicate that Argentavis was fully capable of flight in normal conditions as modern large soaring birds spend very little time flapping their wings regardless of environment.

Feeding

Argentavis' territories measured probably more than 500 square kilometres (190 sq mi), which the birds screened for food, possibly utilizing a generally north–south direction to avoid being slowed by adverse winds. This species seems less aerodynamically suited for predation than its relatives. It probably preferred to scavenge for carrion, and it is possible that it habitually chased metatherian carnivores such as Thylacosmilidae from their kills. The largest land predators in Miocene South America were the giant, ground-dwelling "terror birds", the phorusrhacids. Phorusrhacids were probably the most formidable rivals that Argentavis faced, with the largest species weighing about three times as much as the teratorn. Unlike extant condors and vultures, teratorns generally had long, eagle-like beaks and are believed to have been active predators. This is seemingly true as well of Argentavis but other teratorns were likely far less ponderous considering the substantial size differences. Argentavis may have used its wings and size to intimidate metatherian mammals and small phorusrhacids from their kills. Argentavis may have also ambushed some small live prey, i.e. large rodents, small armadillos and the young of large animals such as ground sloths. The species would've required about 2.5 to 5 kg (5.5 to 11.0 lb) of meat each day. When hunting actively, A. magnificens would probably have swooped from high above onto their prey, which they usually would have been able to grab prey by its bill, kill, and swallow without landing. However, they may too have lain in wait from a ground position, which would render them likely grounded until heavy winds allowed them to fly. Skull structure suggests that it ate most of its prey whole rather than tearing off pieces of flesh.