Amazon River facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Amazon River |

|

|---|---|

Satellite image of the Amazon Delta

|

|

Amazon River and its drainage basin

|

|

| Other name(s) | Rio Amazonas |

| Country | Peru, Colombia, Brazil |

| Cities | Iquitos (Peru); Leticia (Colombia); Tabatinga (Brazil); Tefé (Brazil); Itacoatiara (Brazil) Parintins (Brazil); Óbidos (Brazil); Santarém (Brazil); Almeirim (Brazil); Macapá (Brazil); Manaus (Brazil) |

| Physical characteristics | |

| Main source | Apurímac River, Mismi Peak Arequipa Region, Peru 5,220 m (17,130 ft) 15°31′04″S 71°41′37″W / 15.51778°S 71.69361°W |

| River mouth | Atlantic Ocean Brazil 0°42′28″N 50°5′22″W / 0.70778°N 50.08944°W |

| Length | 3,750 km (2,330 mi)

(Amazon–Ucayali–Tambo–Ené– Apurimac 6,400 km (4,000 mi) to 6,500 km (4,000 mi) (Amazon–Marañón 5,700 km (3,500 mi) |

| Width |

|

| Depth |

|

| Discharge (location 2) |

(Basin size: 6,743,000 km2 (2,603,000 sq mi) to 7,000,000 km2 (2,700,000 sq mi) |

| Discharge (location 3) |

46,130 m3/s (1,629,000 cu ft/s)(Year: 2023)

(Year: 2022)406,000 m3/s (14,300,000 cu ft/s) |

| Discharge (location 4) |

(Period: 1903–2023)95,000 m3/s (3,400,000 cu ft/s)

(Period: 1971–2000)173,272.6 m3/s (6,119,060 cu ft/s) (Period: 1928–1996)176,177 m3/s (6,221,600 cu ft/s) (Period: 01/01/1997–31/12/2015)178,193.9 m3/s (6,292,860 cu ft/s)

(Period: 1903–2023)260,000 m3/s (9,200,000 cu ft/s) 394,000 m3/s (13,900,000 cu ft/s)(Year: 1953) |

| Discharge (location 5) |

105,720 m3/s (3,733,000 cu ft/s) |

| Basin features | |

| Basin size | 7,000,000 km2 (2,700,000 sq mi) 6,743,000 km2 (2,603,000 sq mi) |

| Tributaries |

|

The Amazon River ( Spanish: Río Amazonas, Portuguese: Rio Amazonas) in South America is the largest river by discharge volume of water in the world, and the longest or second-longest river system in the world, a title which is disputed with the Nile.

The headwaters of the Apurímac River on Nevado Mismi had been considered for nearly a century the Amazon basin's most distant source until a 2014 study found it to be the headwaters of the Mantaro River on the Cordillera Rumi Cruz in Peru. The Mantaro and Apurímac rivers join, and with other tributaries form the Ucayali River, which in turn meets the Marañón River upstream of Iquitos, Peru, forming what countries other than Brazil consider to be the main stem of the Amazon. Brazilians call this section the Solimões River above its confluence with the Rio Negro forming what Brazilians call the Amazon at the Meeting of Waters (Portuguese: Encontro das Águas) at Manaus, the largest city on the river.

The Amazon River has an average discharge of about 215,000–230,000 m3/s (7,600,000–8,100,000 cu ft/s)—approximately 6,591–7,570 km3 (1,581–1,816 cu mi) per year, greater than the next seven largest independent rivers combined. Two of the top ten rivers by discharge are tributaries of the Amazon river. The Amazon represents 20% of the global riverine discharge into oceans. The Amazon basin is the largest drainage basin in the world, with an area of approximately 7,000,000 km2 (2,700,000 sq mi). The portion of the river's drainage basin in Brazil alone is larger than any other river's basin. The Amazon enters Brazil with only one-fifth of the flow it finally discharges into the Atlantic Ocean, yet already has a greater flow at this point than the discharge of any other river in the world.

History

Recent geological studies suggest that for millions of years the Amazon River used to flow in the opposite direction - from east to west. Eventually the Andes Mountains formed, blocking its flow to the Pacific Ocean, and causing it to switch directions to its current mouth in the Atlantic Ocean.

Pre-Columbian era

There is ample evidence that the areas surrounding the Amazon River were home to complex and large-scale indigenous societies, mainly chiefdoms who developed towns and cities. Archaeologists estimate that by the time the Spanish conquistador De Orellana traveled across the Amazon in 1541, more than 3 million indigenous people lived around the Amazon. These pre-Columbian settlements created highly developed civilizations.

Arrival of Europeans

In March 1500, Spanish conquistador Vicente Yáñez Pinzón was the first documented European to sail up the Amazon River. Pinzón called the stream Río Santa María del Mar Dulce, later shortened to Mar Dulce, literally, sweet sea, because of its freshwater pushing out into the ocean. Another Spanish explorer, Francisco de Orellana, was the first European to travel from the origins of the upstream river basins, situated in the Andes, to the mouth of the river. In this journey, Orellana baptized some of the affluents of the Amazonas like Rio Negro, Napo and Jurua. The name Amazonas is thought to be taken from the native warriors that attacked this expedition, mostly women, that reminded De Orellana of the mythical female Amazon warriors from the ancient Hellenic culture in Greece (see also Origin of the name).

Exploration

Gonzalo Pizarro set off in 1541 to explore east of Quito into the South American interior in search of El Dorado, the "city of gold" and La Canela, the "valley of cinnamon". He was accompanied by his second-in-command Francisco de Orellana. After 170 km (106 mi), the Coca River joined the Napo River (at a point now known as Puerto Francisco de Orellana); the party stopped for a few weeks to build a boat just upriver from this confluence. They continued downriver through an uninhabited area, where they could not find food. Orellana offered and was ordered to follow the Napo River, then known as Río de la Canela ("Cinnamon River"), and return with food for the party. Based on intelligence received from a captive native chief named Delicola, they expected to find food within a few days downriver by ascending another river to the north.

De Orellana took about 57 men, the boat, and some canoes and left Pizarro's troops on 26 December 1541. However, De Orellana missed the confluence (probably with the Aguarico) where he was searching supplies for his men. By the time he and his men reached another village, many of them were sick from hunger and eating "noxious plants", and near death. Seven men died in that village. His men threatened to mutiny if the expedition turned back to attempt to rejoin Pizarro, the party being over 100 leagues downstream at this point. He accepted to change the purpose of the expedition to discover new lands in the name of the king of Spain, and the men built a larger boat in which to navigate downstream. After a journey of 600 km (370 mi) down the Napo River, they reached a further major confluence, at a point near modern Iquitos, and then followed the upper Amazon, now known as the Solimões, for a further 1,200 km (746 mi) to its confluence with the Rio Negro (near modern Manaus), which they reached on 3 June 1542.

Regarding the initial mission of finding cinnamon, Pizarro reported to the king that they had found cinnamon trees, but that they could not be profitably harvested. True cinnamon (Cinnamomum Verum) is not native to South America. Other related cinnamon-containing plants (of the family Lauraceae) are fairly common in that part of the Amazon and Pizarro probably saw some of these. The expedition reached the mouth of the Amazon on 24 August 1542, demonstrating the practical navigability of the Great River.

In 1560, another Spanish conquistador, Lope de Aguirre, may have made the second descent of the Amazon. Historians are uncertain whether the river he descended was the Amazon or the Orinoco River, which runs more or less parallel to the Amazon further north.

Portuguese explorer Pedro Teixeira was the first European to travel up the entire river. He arrived in Quito in 1637, and returned via the same route.

From 1648 to 1652, Portuguese Brazilian bandeirante António Raposo Tavares led an expedition from São Paulo overland to the mouth of the Amazon, investigating many of its tributaries, including the Rio Negro, and covering a distance of over 10,000 km (6,200 mi).

In what is currently in Brazil, Ecuador, Bolivia, Colombia, Peru, and Venezuela, several colonial and religious settlements were established along the banks of primary rivers and tributaries for trade, slaving , and evangelization among the indigenous peoples of the vast rainforest, such as the Urarina. In the late 1600s, Czech Jesuit Father Samuel Fritz, an apostle of the Omagus established some forty mission villages. Fritz proposed that the Marañón River must be the source of the Amazon, noting on his 1707 map that the Marañón "has its source on the southern shore of a lake that is called Lauricocha, near Huánuco." Fritz reasoned that the Marañón is the largest river branch one encounters when journeying upstream, and lies farther to the west than any other tributary of the Amazon. For most of the 18th–19th centuries and into the 20th century, the Marañón was generally considered the source of the Amazon.

Scientific exploration

Early scientific, zoological, and botanical exploration of the Amazon River and basin took place from the 18th century through the first half of the 19th century.

- Charles Marie de La Condamine explored the river in 1743.

- Alexander von Humboldt, 1799–1804

- Johann Baptist von Spix and Carl Friedrich Philipp von Martius, 1817–1820

- Georg von Langsdorff, 1826–1828

- Henry Walter Bates and Alfred Russel Wallace, 1848–1859

- Richard Spruce, 1849–1864

Post-colonial exploitation and settlement

The population of the Brazilian portion of the Amazon basin in 1850 was perhaps 300,000, of whom about 175,000 were Europeans and 25,000 were slaves. The Brazilian Amazon's principal commercial city, Pará (now Belém), had from 10,000 to 12,000 inhabitants, including slaves. The town of Manáos, now Manaus, at the mouth of the Rio Negro, had a population between 1,000 and 1,500. All the remaining villages, as far up as Tabatinga, on the Brazilian frontier of Peru, were relatively small.

On 6 September 1850, Emperor Pedro II of Brazil sanctioned a law authorizing steam navigation on the Amazon and gave the Viscount of Mauá (Irineu Evangelista de Sousa) the task of putting it into effect. He organised the "Companhia de Navegação e Comércio do Amazonas" in Rio de Janeiro in 1852; in the following year it commenced operations with four small steamers, the Monarca ('Monarch'), the Cametá, the Marajó and the Rio Negro.

At first, navigation was principally confined to the main river; and even in 1857 a modification of the government contract only obliged the company to a monthly service between Pará and Manaus, with steamers of 200 tons cargo capacity, a second line to make six round voyages a year between Manaus and Tabatinga, and a third, two trips a month between Pará and Cametá. This was the first step in opening up the vast interior.

The success of the venture called attention to the opportunities for economic exploitation of the Amazon, and a second company soon opened commerce on the Madeira, Purús, and Negro; a third established a line between Pará and Manaus, and a fourth found it profitable to navigate some of the smaller streams. In that same period, the Amazonas Company was increasing its fleet. Meanwhile, private individuals were building and running small steam craft of their own on the main river as well as on many of its tributaries.

On 31 July 1867, the government of Brazil, constantly pressed by the maritime powers and by the countries encircling the upper Amazon basin, especially Peru, decreed the opening of the Amazon to all countries, but they limited this to certain defined points: Tabatinga – on the Amazon; Cametá – on the Tocantins; Santarém – on the Tapajós; Borba – on the Madeira, and Manaus – on the Rio Negro. The Brazilian decree took effect on 7 September 1867.

Thanks in part to the mercantile development associated with steamboat navigation coupled with the internationally driven demand for natural rubber, the Peruvian city of Iquitos became a thriving, cosmopolitan center of commerce. Foreign companies settled in Iquitos, from where they controlled the extraction of rubber. In 1851 Iquitos had a population of 200, and by 1900 its population reached 20,000. In the 1860s, approximately 3,000 tons of rubber were being exported annually, and by 1911 annual exports had grown to 44,000 tons, representing 9.3% of Peru's exports. During the rubber boom it is estimated that diseases brought by immigrants, such as typhus and malaria, killed 40,000 native Amazonians.

The first direct foreign trade with Manaus commenced around 1874. Local trade along the river was carried on by the English successors to the Amazonas Company—the Amazon Steam Navigation Company—as well as numerous small steamboats, belonging to companies and firms engaged in the rubber trade, navigating the Negro, Madeira, Purús, and many other tributaries, such as the Marañón, to ports as distant as Nauta, Peru.

By the turn of the 20th century, the exports of the Amazon basin were India-rubber, cacao beans, Brazil nuts and a few other products of minor importance, such as pelts and exotic forest produce (resins, barks, woven hammocks, prized bird feathers, live animals) and extracted goods, such as lumber and gold.

20th-century

With a population of 1.9 million people in 2014, Manaus is the largest city on the Amazon. Manaus alone makes up approximately 50% of the population of the largest Brazilian state of Amazonas. The racial makeup of the city is 64% pardo (mulatto and mestizo) and 32% white.

Although the Amazon river remains undammed, around 412 dams are in operation on the Amazon's tributary rivers. Of these 412 dams, 151 are constructed over six of the main tributary rivers that drain into the Amazon. Since only 4% of the Amazon's hydropower potential has been developed in countries like Brazil, more damming projects are underway and hundreds more are planned.

Flora and fauna

Flora

Fauna

More than one-third of all known species in the world live in the Amazon rainforest. It is the richest tropical forest in the world in terms of biodiversity. In addition to thousands of species of fish, the river supports crabs, algae, and turtles.

Mammals

Along with the Orinoco, the Amazon is one of the main habitats of the boto, also known as the Amazon river dolphin (Inia geoffrensis). It is the largest species of river dolphin, and it can grow to lengths of up to 2.6 m (8.5 ft). The colour of its skin changes with age; young animals are gray, but become pink and then white as they mature. The dolphins use echolocation to navigate and hunt in the river's tricky depths.

The tucuxi (Sotalia fluviatilis), also a dolphin species, is found both in the rivers of the Amazon basin and in the coastal waters of South America. The Amazonian manatee (Trichechus inunguis), also known as "seacow", is found in the northern Amazon River basin and its tributaries. It is a mammal and a herbivore. Its population is limited to freshwater habitats, and, unlike other manatees, it does not venture into saltwater. It is classified as vulnerable by the International Union for Conservation of Nature.

The Amazon and its tributaries are the main habitat of the giant otter (Pteronura brasiliensis). Sometimes known as the "river wolf," it is one of South America's top carnivores. Because of habitat destruction and hunting, its population has dramatically decreased. It is now listed on Appendix I of the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES), which effectively bans international trade.

Reptiles

The Anaconda is found in shallow waters in the Amazon basin. One of the world's largest species of snake, the anaconda spends most of its time in the water with just its nostrils above the surface. Species of caimans, that are related to alligators and other crocodilians, also inhabit the Amazon as do varieties of turtles.

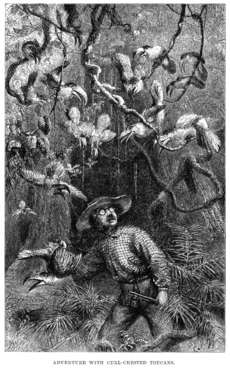

Birds

Fish

The Amazonian fish fauna is the centre of diversity for neotropical fishes, some of which are popular aquarium specimens like the neon tetra and the freshwater angelfish. More than 5,600 species were known as of 2011[update], and approximately fifty new species are discovered each year. The arapaima, known in Brazil as the pirarucu, is a South American tropical freshwater fish, one of the largest freshwater fish in the world, with a length of up to 15 feet (4.6 m). Another Amazonian freshwater fish is the arowana (or aruanã in Portuguese), such as the silver arowana (Osteoglossum bicirrhosum), which is a predator and very similar to the arapaima, but only reaches a length of 120 cm (47 in). Also present in large numbers is the notorious piranha, an omnivorous fish that congregates in large schools and may attack livestock. There are approximately 30 to 60 species of piranha. The candirú, native to the Amazon River, is a species of parasitic fresh water catfish in the family Trichomycteridae, just one of more than 1200 species of catfish in the Amazon basin. Other catfish 'walk' overland on their ventral fins, while the kumakuma (Brachyplatystoma filamentosum), aka piraiba or "goliath catfish", can reach 3.6 m (12 ft) in length and 200 kg (440 lb) in weight.

The electric eel (Electrophorus electricus) and more than 100 species of electric fishes (Gymnotiformes) inhabit the Amazon basin. River stingrays (Potamotrygonidae) are also known. The bull shark (Carcharhinus leucas) has been reported 4,000 km (2,500 mi) up the Amazon River at Iquitos in Peru.

Butterflies

Microbiota

Freshwater microbes are generally not very well known, even less so for a pristine ecosystem like the Amazon. Recently, metagenomics has provided answers to what kind of microbes inhabit the river. The most important microbes in the Amazon River are Actinomycetota, Alphaproteobacteria, Betaproteobacteria, Gammaproteobacteria and Thermoproteota.

Protected areas

| Name | Country | Coordinates | Image | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Allpahuayo-Mishana National Reserve | Peru | 3°56′S 73°33′W / 3.933°S 73.550°W | ||

| Amacayacu National Park | Colombia | 3°29′S 72°12′W / 3.483°S 72.200°W | ||

| Amazônia National Park | Brazil | 4°26′S 56°50′W / 4.433°S 56.833°W | ||

| Anavilhanas National Park | Brazil | 2°23′S 60°55′W / 2.383°S 60.917°W |

Bridges

There are no bridges across the entire width of the river. This is not because the river would be too wide to bridge; for most of its length, engineers could build a bridge across the river easily. For most of its course, the river flows through the Amazon Rainforest, where there are very few roads and cities. Most of the time, the crossing can be done by a ferry. The Manaus Iranduba Bridge linking the cities of Manaus and Iranduba spans the Rio Negro, the second-largest tributary of the Amazon, just before their confluence.

Challenges

The Amazon River serves as a vital lifeline for more than 47 million people in its basin and faces a multitude of challenges that threaten both its ecosystem and the indigenous communities dependent on its resources. According to the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR), the Yanomami, a tribe of approximately 29,000, struggles to preserve their land, culture, and traditional way of life due to encroaching illegal gold miners, malnutrition, and malaria. Meanwhile, in 2022, the region's severe drought, has led to a devastating increase in water temperatures, reaching 39.1 degrees Celsius, causing the demise of 125 Amazon river dolphins. This event displays the deteriorating environmental conditions and indicates the increasing vulnerability of the river's ecosystem. In recent years, the Amazon River has experienced historically low water levels, the lowest in over a century. Brazil, the primary custodian of this invaluable natural resource, grapples with the challenges of mitigating the effects of this drought on communities and ecosystems, further emphasizing the urgency of sustainable environmental management and conservation efforts.

Major tributaries

The Amazon has over 1,100 tributaries, twelve of which are over 1,500 km (930 mi) long. Some of the more notable ones are:

List of major tributaries

The main river and tributaries are (sorted in order from the confluence of Ucayali and Marañón rivers to the mouth):

| Left tributary | Right tributary | Length (km) | Basin size (km2) | Average discharge (m3/s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Upper Amazon

(Confluence of Ucayali and Marañón rivers - Tabatinga) |

||||

| Marañón | 2,112 | 364,873.4 | 16,708 | |

| Ucayali | 2,738 | 353,729.3 | 13,630.1 | |

| Tahuyo | 80 | 1,630 | 105.7 | |

| Tamshiyaçu | 86.7 | 1,367.3 | 86.5 | |

| Itaya | 213 | 2,668 | 161.4 | |

| Nanay | 483 | 16,673.4 | 1,072.7 | |

| Maniti | 198.7 | 2,573.6 | 180.4 | |

| Napo | 1,075 | 103,307.8 | 7,147.8 | |

| Apayaçu | 50 | 2,393.6 | 160.9 | |

| Orosa | 95 | 3,506.8 | 234.3 | |

| Ampiyaçu | 140 | 4,201.4 | 267.2 | |

| Chichita | 48 | 1,314.2 | 87.7 | |

| Cochiquinas | 49 | 2,362.7 | 150.2 | |

| Santa Rosa | 45 | 1,678 | 101.5 | |

| Cajocumal | 58 | 2,094.9 | 141.5 | |

| Atacuari | 108 | 3,480.5 | 236.8 | |

| Middle Amazon

(Tabatinga - Encontro das Águas) |

||||

| Javary | 1,056 | 99,674.1 | 5,222.5 | |

| Igarapé

Veneza |

943.9 | 58.3 | ||

| Tacana | 541 | 35.5 | ||

| Igarapé de

Belém |

1,299.9 | 85.4 | ||

| Igarapé São

Jerônimo |

1,259.6 | 78.2 | ||

| Jandiatuba | 520 | 14,890.4 | 980 | |

| Igarapé

Acuruy |

2,462.1 | 127.1 | ||

| Putumayo | 1,813 | 121,115.8 | 8,519.9 | |

| Tonantins | 2,955.2 | 169.2 | ||

| Jutai | 1,488 | 78,451.5 | 4,000 | |

| Juruá | 3,283 | 190,573 | 6,662.1 | |

| Uarini | 7,195.8 | 432.9 | ||

| Japurá | 2,816 | 276,812 | 18,121.6 | |

| Tefé | 571 | 24,375.5 | 1,190.4 | |

| Caiambe | 2,650.1 | 90 | ||

| Parana Copea | 10,532.3 | 423.8 | ||

| Coari | 599 | 35,741.3 | 1,389.3 | |

| Mamiá | 5,514 | 176.2 | ||

| Badajos | 413 | 21,575 | 1,300 | |

| Igarapé Miuá | 1,294.5 | 56.9 | ||

| Purus | 3,382 | 378,762.4 | 11,206.9 | |

| Paraná Arara | 1,915.7 | 78.2 | ||

| Paraná

Manaquiri |

1,318.6 | 52.9 | ||

| Manacapuru | 291 | 14,103 | 559.5 | |

| Lower Amazon

(Encontro das Águas - Gurupá) |

||||

| Rio Negro | 2,362 | 714,577.6 | 30,640.8 | |

| Prêto da Eva | 3,039.5 | 110.8 | ||

| Igapó-Açu | 500 | 45,994.4 | 1,676.5 | |

| Madeira | 3,380 | 1,322,782.4 | 32,531.9 | |

| Urubu | 430 | 13,892 | 459.8 | |

| Uatumã | 701 | 67,920 | 2,290.8 | |

| Canumã,

Paraná do Urariá |

400 | 127,116 | 4,804.4 | |

| Nhamundá,

Trombetas |

744 | 150,032 | 4,127 | |

| Curuá | 484 | 28,099 | 470.1 | |

| Lago Grande

do Curuaí |

3,293.6 | 92.7 | ||

| Tapajós | 1,992 | 494,551.3 | 13,540 | |

| Curuá-Una | 315 | 24,505 | 729.8 | |

| Maicurú | 546 | 18,546 | 272.3 | |

| Uruará | 4,610.2 | 104.8 | ||

| Jauari | 5,851 | 108.3 | ||

| Guajará | 4,243 | 105.6 | ||

| Paru de Este | 731 | 39,289 | 970 | |

| Xingu | 2,275 | 513,313.5 | 10,022.6 | |

| Igarapé

Arumanduba |

1,819.9 | 50.8 | ||

| Jari | 769 | 51,893 | 1,213.5 | |

| Amazon Delta

(river mouth to Gurupá) |

||||

| Braco do

Cajari |

4,732.4 | 157.1 | ||

| Pará | 784 | 84,027 | 3,500.3 | |

| Tocantins | 2,639 | 777,308 | 11,796 | |

| Atuã | 2,769 | 119.8 | ||

| Anajás | 300 | 24,082.5 | 948 | |

| Mazagão | 1,250.2 | 44.4 | ||

| Vila Nova | 5,383.8 | 180.8 | ||

| Matapi | 2,487.4 | 81.7 | ||

| Acará,

Guamá |

400 | 87,389.5 | 2,550.7 | |

| Arari | 1,523.6 | 80.2 | ||

| Pedreira | 2,005 | 89.9 | ||

| Paracauari | 1,390.3 | 67.9 | ||

| Jupati | 724.2 | 32.6 | ||

List by length

- 6,400 km (4,000 mi) (6,275 to 7,025 km (3,899 to 4,365 mi)) – Amazon, South America

- 3,250 km (2,019 mi) – Madeira, Bolivia/Brazil

- 3,211 km (1,995 mi) – Purús, Peru/Brazil

- 2,820 km (1,752 mi) – Japurá or Caquetá, Colombia/Brazil

- 2,639 km (1,640 mi) – Tocantins, Brazil

- 2,627 km (1,632 mi) – Araguaia, Brazil (tributary of Tocantins)

- 2,400 km (1,500 mi) – Juruá, Peru/Brazil

- 2,250 km (1,400 mi) – Rio Negro, Brazil/Venezuela/Colombia

- 1,992 km (1,238 mi) – Tapajós, Brazil

- 1,979 km (1,230 mi) – Xingu, Brazil

- 1,900 km (1,181 mi) – Ucayali River, Peru

- 1,749 km (1,087 mi) – Guaporé, Brazil/Bolivia (tributary of Madeira)

- 1,575 km (979 mi) – Içá (Putumayo), Ecuador/Colombia/Peru

- 1,415 km (879 mi) – Marañón, Peru

- 1,370 km (851 mi) – Teles Pires, Brazil (tributary of Tapajós)

- 1,300 km (808 mi) – Iriri, Brazil (tributary of Xingu)

- 1,240 km (771 mi) – Juruena, Brazil (tributary of Tapajós)

- 1,130 km (702 mi) – Madre de Dios, Peru/Bolivia (tributary of Madeira)

- 1,100 km (684 mi) – Huallaga, Peru (tributary of Marañón)

List by inflow to the Amazon

| Rank | Name | Average annual discharge (m^3/s) | % of Amazon |

|---|---|---|---|

| Amazon | 209,000 | 100% | |

| 1 | Madeira | 31,200 | 15% |

| 2 | Negro | 28,400 | 14% |

| 3 | Japurá | 18,620 | 9% |

| 4 | Marañón | 16,708 | 8% |

| 5 | Tapajós | 13,540 | 6% |

| 6 | Ucayali | 13,500 | 5% |

| 7 | Purus | 10,970 | 5% |

| 8 | Xingu | 9,680 | 5% |

| 9 | Putumayo | 8,760 | 4% |

| 10 | Juruá | 8,440 | 4% |

| 11 | Napo | 6,976 | 3% |

| 12 | Javari | 4,545 | 2% |

| 13 | Trombetas | 3,437 | 2% |

| 14 | Jutaí | 3,425 | 2% |

| 15 | Abacaxis | 2,930 | 2% |

| 16 | Uatumã | 2,190 | 1% |

See also

In Spanish: Río Amazonas para niños

In Spanish: Río Amazonas para niños