Śūraṅgama Sūtra facts for kids

The Śūraṅgama Sūtra (Chinese: 首楞嚴經; pinyin: Shou-leng-yen ching, Sūtra of the Heroic March) (Taisho no. 945) is a Mahayana Buddhist sutra that has been especially influential on Korean Buddhism (where it remains a major subject of study in Sŏn monasteries) and Chinese Buddhism (where it was a regular part of daily liturgy during the Song). It was particularly important for Zen/Chan Buddhism. The doctrinal outlook of the Śūraṅgama Sūtra is that of Buddha-nature, Yogacara thought, and esoteric Buddhism.

The Śūraṅgama Sūtra was widely accepted as a sutra in East Asian Buddhism, where it has traditionally been included as part of Chinese-language Tripitakas. In the modern Taisho Tripitaka, it is placed in the Esoteric Sutra category (密教部). The sutra's Śūraṅgama Mantra is widely recited in China, Korea, Japan and Vietnam as part of temple liturgies.

Most modern academic scholars (including Mochizuki Shinko, Paul Demieville, Kim Chin-yol, Lü Cheng 呂澂, Charles Muller and Kogen Mizuno), argue that the sutra is a Chinese apocryphal text that was composed in literary Chinese and reveals uniquely Chinese philosophical concerns. However, some scholars such as Ron Epstein argue that the text is a compilation of Indic materials with extensive editing in China.

The sutra was translated into Tibetan during the late eighth to early ninth century and other complete translations exist in Tibetan, Mongolian and Manchu languages (see Translations).

Contents

Title

Śūraṅgama means "heroic valour", "heroic progress", or "heroic march" in Sanskrit.

The name of the Śūraṅgama Sūtra in different languages

A common translation of the sutra's name in English is the "Heroic March sutra" (as used e.g. by Matthew Kapstein, Norman Waddell, and Andy Ferguson), or the "scripture of the Heroic Progress" (as used e.g. by Thomas Cleary).

The full title of the sutra also appears as: traditional Chinese: 大佛頂如來密因修證了義諸菩薩萬行首楞嚴經; ; pinyin: Dà Fódǐng Rúlái Mìyīn Xiūzhèng Liǎoyì Zhū Púsà Wànxíng Shǒuléngyán jīng; Korean: 대불정여래밀인수증료의제보살만행수릉엄경; Vietnamese: Đại Phật đỉnh Như Lai mật nhân tu chứng liễu nghĩa chư Bồ Tát vạn hạnh thủ-lăng-nghiêm kinh.

It is also known by abbreviated versions of the title such as traditional Chinese: 大佛頂首楞嚴經; ; pinyin: Dà Fódǐng Shǒuléngyán jīng; Korean: 대불정수릉엄경; Vietnamese: Đại Phật đỉnh thủ-lăng-nghiêm kinh or simply and more commonly traditional Chinese: 楞嚴經; ; pinyin: Léngyán jīng; Korean: 릉엄경; Vietnamese: lăng-nghiêm kinh.

History

Authorship

The first catalogue that recorded the Śūraṅgama Sūtra was Zhisheng (Chinese: 智昇), a monk in Tang China. Zhisheng said this book was brought back from Guangxi to Luoyang during the reign of Emperor Xuanzong. He gave two different accounts in two different books, both of which were published in 730 CE.

- According to the first account found in The Kaiyuan Era Catalog of the Buddhist Tripitaka (Chinese: 開元釋教錄) the Śūraṅgama Sūtra was translated in 713 CE by a Ven. Master Huai Di (Chinese: 懷迪) and an unnamed Indian monk.

- According to the second account, in his later book Continuation to the History of the Translation of Buddhist Sutras Mural Record (續古今譯經圖記), the Śūraṅgama Sūtra was translated in May 705 CE by Śramaṇa Pāramiti from central India, who came to China and brought the text to the province of Guangzhou. The text was then polished and edited by Empress Wu Zetian's former minister, court regulator, and state censor Fang Yong (Chinese: 房融) of Qingho. The translation was reviewed by Śramaṇa Meghaśikha from Oḍḍiyāna, and certified by Śramaṇa Huai-di (Chinese: 懷迪) of Nanlou Monastery (南樓寺) on Mount Luofu (羅浮山).

Dispute about this text arose in 8th century in Japan, so Emperor Kōnin sent Master Tokusei (Hanyu Pinyin: Deqing; Japanese: 徳清) and a group of monks to China, asking whether this book was a forgery or not. A Chinese upasaka or layperson told the head monk of the Japanese monastic delegation, Master Tokusei that this was forged by Fang Yong. Zhu Xi, a 12th-century Neo-confucian who was opposed to Buddhism, believed that it was created during the Tang Dynasty in China, and did not come from India.

The Qianlong Emperor and the Third Changkya Khutukhtu, the traditional head tulku of the Gelug lineage of Tibetan/Vajrayana Buddhism in Inner Mongolia, believed in the authenticity of the Śūraṅgama Sūtra. They later translated the Śūraṅgama Sūtra into the Manchu language, Mongolian and Tibetan.(see translations)

In China during the early modern era, the reformist Liang Qichao claimed that the sutra is apocryphal, writing, "The real Buddhist scriptures would not say things like Surangama Sutra, so we know the Surangama Sutra is apocryphal. In the same era, Lü Cheng (Chinese: 呂澂) wrote an essay to claim that the book is apocryphal, named "One hundred reasons about why Shurangama Sutra is apocryphal" (Chinese: 楞嚴百偽).

Hurvitz claims that the Śūraṅgama Sūtra is "a Chinese forgery". Faure similarly claims that it is "apocryphal."

Ron Epstein gives an overview of the arguments for Indian or Chinese origin, and concludes:

Preliminary analysis of the internal evidence then indicates that the Sutra is probably a compilation of Indic materials that may have had a long literary history. It should be noted though, that for a compilation, which is also how the Sutra is treated by some traditional commentators, the Sutra has an intricate beauty of structure that is not particularly Chinese and which shines through and can clearly be distinguished from the Classical Chinese syntax, on which attention has usually been centered. Thus one of the difficulties with the theory that the Sutra is apocryphal is that it would be difficult to find an author who could plausibly be held accountable for both structure and language and who would also be familiar with the doctrinal intricacies that the Sutra presents. Therefore, it seems likely that the origin of the great bulk of material in the Sutra is Indic, though it is obvious that the text was edited in China. However, a great deal of further, systematic research will be necessary to bring to light all the details of the text's rather complicated construction.

A number of scholars have associated the Śūraṅgama Sūtra with the Buddhist tradition at Nālandā. Epstein also notes that the general doctrinal position of the sūtra does indeed correspond to what is known about the Buddhist teachings at Nālandā during this period.

Charles Muller and Kogen Mizuno also hold that this sutra is apocryphal (and is similar to other apocryphal Chinese sutras). According to Muller, "even a brief glance" through these apocryphal works "by someone familiar with both indigenous sinitic philosophy and the Indian Mahāyāna textual corpus yields the recognition of themes, terms and concepts from indigenous traditions playing a dominant role in the text, to an extent which makes it obvious that they must have been written in East Asia." He further notes that apocryphal works like the Śūraṅgama contain terms that were only used in East Asia:

...such as innate enlightenment (本覺 pen-chüeh) and actualized enlightenment (始覺 chih-chüeh) and other terms connected with the discourse of the tathāgatagarbha-ālayavijñāna problematik (the debate as to whether the human mind is, at its most fundamental level, pure or impure) appear in such number that the difference from the bona fide translations from Indic languages is obvious. Furthermore, the entire discourse of innate/actualized enlightenment and tathāgatagarbha-ālayavijñāna opposition can be seen as strongly reflecting a Chinese philosophical obsession dating back to at least the time of Mencius, when Mencius entered into debate with Kao-tzu on the original purity of the mind.

Non-Chinese Translations

The Śūraṅgama Sūtra was translated into Tibetan probably during the late eighth to early ninth century. However possibly because of the persecution of Buddhism during King Langdarma’s reign (ca. 840-841), only a portion of Scroll 9 and Scroll 10 of the Śūraṅgama Sūtra are preserved in the surviving two ancient texts. Interesting enough, Buton Rinchen Drub Rinpoche mentioned that one of the two texts was probably translated from Chinese; thereby suggesting the second text may have possibly been translated from Sanskrit (or another language).

The entire Śūraṅgama Sūtra was translated in 1763 from Chinese into the Manchu language, Mongolian and Tibetan languages and compiled into a quadralingual set by command of the Qianlong Emperor. The third Changkya Khutukhtu Rölpé Dorjé or 若必多吉 or Lalitavajra (1716–1786) convinced the Qianlong Emperor to engage in the translation. The third Changkya Khutukhtu supervised (and verified) with the help of Fu Nai the translation of the Śūraṅgama Sūtra. The complete translation of the Śūraṅgama Sūtra into Tibetan is found in a supplement to the Narthang Kangyur.

There are a few English translations:

- The Surangama Sutra published in A Buddhist Bible translated by Dwight Goddard and Bhikshu Wai-tao.

- The Shurangama Sutra with commentary by Master Hsuan Hua. Volumes 1 to 8. Buddhist Translation Society, 2nd edition (October 2003).

- A New Translation Buddhist Text Translation Society. The Śūraṅgama Sūtra With Excerpts from the Commentary by the Venerable Master Hsüan Hua

- Charles Luk, 1967, Shurangama Sutra

- Hsuan Hua, 1977, The Shurangama Sutra, Vol.1-8, by Buddhist Text Translation Society Staff (Author)

Teachings

Doctrinal orientation

The Śūraṅgama Sūtra contains teachings from Yogācāra, Buddha-nature, and Vajrayana. It makes use of Buddhist logic with its methods of syllogism and the catuṣkoṭi "fourfold negation" first popularized by Nāgārjuna.

Main themes

Some of the main themes of the Śūraṅgama Sūtra are the worthlessness of the Dharma when unaccompanied by samādhi power, and the importance of moral precepts as a foundation for the Buddhist practice. Also stressed is the theme of how one effectively combats delusions that may arise during meditation.

Ron Epstein and David Rounds have suggested that the major themes of the Śūraṅgama Sūtra reflect the strains upon Indian Buddhism during the time of its creation. They cite the resurgence of tribal influences, and the crumbling social supports for monastic Buddhist institutions. This era also saw the emergence of Hindu tantrism and the beginnings of Esoteric Buddhism and the siddha traditions. They propose that moral challenges and general confusion about Buddhism are said to have then given rise to the themes of the Śūraṅgama Sūtra, such as clear understanding of principles, moral discipline, essential Buddhist cosmology, development of samādhi, and how to avoid falling into various delusions in meditation.

Two types of mind

David Rounds notes that the Buddha makes a very important distinction when teaching his cousin, Ananda, about his mind that there are in fact not one, but two different types of mind (that are fundamentally different in their natures) that we need to be aware of in our spiritual cultivation:

"The Buddha then compounds his cousin's confusion by stating that there are fundamentally two kinds of mind:

1. First, the ordinary quotidian mind of which we are aware and which is entangled, lifetime after lifetime, in the snare of illusory perceptions and random thoughts;

2. And second, the everlasting true mind, which is our real nature, and which is the state of the Buddha."

Ananda, what are the two fundamentals?

The first is the mind that is the basis of death and rebirth and that has continued for the entirety of time, which has no beginning. This mind is dependent upon perceived objects, and it is this that you and all beings make use of and that each of you consider to be your own nature.

The second fundamental is enlightenment, which has no beginning; it is the original and pure essence of nirvana.

Tathagatagarbha

Rounds and Epstein explain the Buddha Nature, the Matrix of the Thus Come One as spoken of in the Surangama Sutra:

Fundamentally, everything that comes and goes, that comes into being and ceases to be, is within the true nature of the Matrix of the Thus-Come One, which is the wondrous, everlasting understanding — the unmoving, all-pervading, wondrous suchness of reality.

[The Buddha] shows one by one that each of the elements of the physical world and each of the elements of our sensory apparatus is, fundamentally, an illusion. But at the same time, these illusory entities and experiences arise out of what is real. That matrix from which all is produced is the Matrix of the Thus-Come One. It is identical to our own true mind and identical as well to the fundamental nature of the universe and to the mind of all Buddhas.

Śūraṅgama Samādhi

The Śūraṅgama Sūtra teaches about the Śūraṅgama Samādhi, which is associated with complete enlightenment and Buddhahood. This samādhi is also featured extensively in the Śūraṅgama Samādhi Sūtra, another Mahāyāna text. It is equally praised in the Mahāparinirvāṇa Sūtra, where it is explained by the Buddha that this samādhi is the essence of the nature of the Buddha and is indeed the "mother of all Buddhas." The Buddha also comments that the Śūraṅgama Samādhi additionally goes under several other names, specifically Prajñāpāramitā ("Perfection of Wisdom"), the Vajra Samādhi ("Diamond Samadhi"), the Siṃhanāda Samādhi ("Lion's Roar Samādhi"), and the Buddhasvabhāva ("Buddha-nature").

White Parasol Crown Dhāraṇī

In addition to the sūtra's contents, the dhāraṇī contained in it is known in Chinese as the Léngyán Zhòu (楞嚴咒), or Śūraṅgama Mantra. It is well-known and popularly chanted in East Asian Buddhism. In Sanskrit, the dhāraṇī is known as the "Sitātapatra Uṣṇīṣa Dhāraṇī" (Ch. 大白傘蓋陀羅尼). This is sometimes simplified in English to "White Canopy Dhāraṇī" or "White Parasol Dhāraṇī." In Tibetan traditions, the English is instead sometimes rendered as the "White Umbrella Mantra." The dhāraṇī is extant in three other translations found in the Chinese Buddhist canon, and is also preserved in Sanskrit and Tibetan.

According to Venerable Hsuan Hua, the dhāraṇī contains five major divisions, which "control the vast demon armies of the five directions":

- In the East is the Vajra Division, hosted by Akṣobhya

- In the South, the Jewel-creating Division, hosted by Ratnasaṃbhava

- In the center, the Buddha Division, hosted by Vairocana

- In the West, the Lotus Division, hosted by Amitābha

- In the North, the Karma Division, hosted by Amoghasiddhi

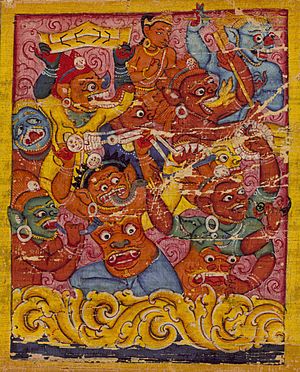

Fifty skandha-māras

Māras as manifestations of the five skandhas are described in the Śūraṅgama Sūtra. In its section on the fifty skandha-māras, each of the five skandhas has ten skandha-māras associated with it, and each skandha-māra is described in detail as a deviation from correct samādhi. These skandha-māras are also known as the "fifty skandha demons" in some English-language publications. Epstein introduces the fifty skandha-māras section as follows:

For each state a description is given of the mental phenomena experienced by the practitioner, the causes of the phenomena and the difficulties which arise from attachment to the phenomena and misinterpretation of them. In essence what is presented is both a unique method of cataloguing and classifying spiritual experience and indication of causal factors involved in the experience of the phenomena. Although the fifty states presented are by no means exhaustive, the approach taken has the potential of offering a framework for the classification of all spiritual experience, both Buddhist and non-Buddhist.

The Three Non-Outflow Studies

The Buddha explained five foremost precepts which must be upheld.

- One Must Cut Off Killing

- One Must Cut Off Stealing

- One Must Cut Off Desire

- One Must Cut Off False Speech

- One Must Cut Off Drinking

These precepts are the basis to samadhi which in turn reveals wisdom. The Buddha describes these four rules as clear and unalterable instruction on purity which transverse time and place. The same instructions were also transmitted from former Buddhas.

Even though one may have some wisdom and the manifestation of Chan samadhi, one is certain to enter the path of demons, spirits and deviants if he does not cease desire, killing and stealing respectively. Such people will revolve in the three paths and are bound to sink into the bitter sea of birth and death when their retribution ends.

If people make false claims to be Buddha or certified sages, such people will lose proper knowledge and vision, and later fall into sufferings of hells.

Influence

China

The Śūraṅgama Sūtra has been widely studied and commented on in China. Ron Epstein...

... found reference to 127 Chinese commentaries on the Sutra, quite a few for such a lengthy work, including 59 in the Ming dynasty alone, when it was especially popular ".

The Śūraṅgama Sūtra is one of the seminal texts of Chán Buddhism. It was first transmitted by Yuquan Shenxiu, the original sixth patriarch and the seminal figure of the Northern school. It "is connected with the enlightenment of" Changshui Zixuan from the Song dynasty and Hanshan Deqing (憨山德清) from the Ming.

The Śūraṅgama Sūtra is being cited in case 94 of the Blue Cliff Record:

In the Surangama Sutra the Buddha says, "When unseeing, why do you not see the unseeing? If you see the unseeing, it is no longer unseeing. If you do not see the unseeing, it is not an object. Why isn't it yourself?"

Dōgen commented on the verse "When someone gives rise to Truth by returning to the Source, the whole of space in all ten quarters falls away and vanishes":

This verse has been cited by various Buddhas and Ancestors alike. Up to this very day, this verse is truly the Bones and Marrow of the Buddhas and Ancestors. It is the very Eye of the Buddhas and Ancestors. As to my intention in saying so, there are those who say that the ten-fascicle Shurangama Scripture is a spurious scripture, whereas others say that it is a genuine Scripture: both views have persisted from long in the past down to our very day [...] Even were the Scripture a spurious one, if [Ancestors] continue to offer its turning, then it is a genuine Scripture of the Buddhas and Ancestors, as well as the Dharma Wheel intimately associated with Them.

The contemporary Chán-master Venerable Hsu Yun wrote a commentary on the Śūraṅgama Sūtra. Venerable Hsuan Hua was a major modern proponent of the Śūraṅgama Sūtra, which he commented and used in his instructions on protecting and supporting the Proper Dharma. About the Śūraṅgama Sūtra, he said:

In Buddhism all the sutras are very important, but the Śūraṅgama Sūtra is most important. Wherever the Śūraṅgama Sūtra is, the Proper Dharma abides in the world. When the Śūraṅgama Sūtra is gone, the Dharma Ending Age is before one's eyes. (In the Extinction of the Dharma Sutra it says that in the Dharma Ending Age, the Śūraṅgama Sūtra will become extinct first. Then gradually the other sutras will also become extinct.) The Śūraṅgama Sūtra is the true body of the Buddha; the śarīra (relics) of the Buddha; the stūpa of the Buddha. All Buddhists must support with their utmost strength The Śūraṅgama Sūtra

The Śūraṅgama Mantra which is found within the Śūraṅgama Sūtra, is recited in China, Korea and Vietnam by Mahayana monastics on a daily basis and by some laypersons as part of the Morning Recitation Liturgy.

In China and Vietnam, it is the first mantra traditionally recited in the morning recitation services. The mantra is also recited by some Japanese Buddhist sects.

See also

In Spanish: Śūraṃgama sūtra para niños

In Spanish: Śūraṃgama sūtra para niños