Wu Zetian facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Wu Zetian武則天 |

|||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Wu Zetian depicted wearing 18th century Ming dynasty clothing taken from An 18th century album of portraits of 86 emperors of China, with Chinese historical notes. (British Library, shelfmark Or. 2231)

|

|||||||||||||||||

| Empress regnant of China | |||||||||||||||||

| Reign | 16 October 690 – 21 February 705 | ||||||||||||||||

| Coronation | 16 October 690 | ||||||||||||||||

| Predecessor | Dynasty established (Emperor Ruizong as Emperor of the Tang Dynasty) |

||||||||||||||||

| Successor | Dynasty abolished (Emperor Zhongzong as Emperor of the Tang dynasty) |

||||||||||||||||

| Empress dowager of China | |||||||||||||||||

| Tenure | 27 December 683 – 16 October 690 | ||||||||||||||||

| Empress consort of China | |||||||||||||||||

| Tenure | 22 November 655 – 27 December 683 | ||||||||||||||||

| Born | 17 February 624 Lizhou, Tang China |

||||||||||||||||

| Died | 16 December 705 (aged 81) Luoyang, Tang China |

||||||||||||||||

| Burial | Qianling Mausoleum | ||||||||||||||||

| Spouse | |||||||||||||||||

| Issue |

|

||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||

| House | Wǔ (武) | ||||||||||||||||

| Dynasty |

|

||||||||||||||||

| Father | Wu Shiyue | ||||||||||||||||

| Mother | Lady Yang | ||||||||||||||||

| Religion | Buddhism | ||||||||||||||||

| Wu Zetian | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Chinese | 武則天 | ||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 武则天 | ||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||

| Wu Zhao | |||||||||||||||||

| Chinese | 武曌 | ||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||

| Wu Hou | |||||||||||||||||

| Chinese | 武后 | ||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||

| Tian Hou | |||||||||||||||||

| Chinese | 天后 | ||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||

Wu Zetian (17 February 624 – 16 December 705), personal name Wu Zhao, was the first and only female emperor in Chinese history, and de facto ruler of the Tang dynasty from 665 to 705, ruling first through others and then (from 690) in her own right. From 665 to 690, she was first empress consort of the Tang dynasty (as wife of the Emperor Gaozong) and then, after his death, empress dowager (ruling through her sons Emperors Zhongzong and Ruizong). Unprecedented in Chinese history, she subsequently founded and ruled as female emperor of the Wu Zhou dynasty of China from 690 to 705. She was the only female sovereign in the history of China widely regarded as legitimate. Under her 40-year reign, China grew larger, becoming one of the great powers of the world, its culture and economy were revitalized, and corruption in the court was reduced. She was removed from power in a coup and died a few months later.

In early life, Wu was the concubine of Emperor Taizong. After his death, she married his ninth son and successor, Emperor Gaozong, officially becoming Gaozong's huanghou (皇后), or empress consort, the highest-ranking of the wives, in 655. Even before becoming empress consort, Wu had considerable political power. Once announced as the empress consort, she began to control the court, and after Gaozong's debilitating stroke in 660, she became administrator of the court, a position equal to the emperor's, until 705. After Gaozong's death, Wu as empress dowager and regent held power completely and solely, used absolute power more forcefully and violently than before, and suppressed her overt and covert opponents. Seven years later, Wu seized the throne and began the Zhou dynasty, becoming the only empress regnant in Chinese history.

Empress Wu is considered one of the greatest emperors in Chinese history due to her strong leadership and effective governance, which made China one of the world's most powerful nations. The importance to history of her tenure includes the major expansion of the Chinese empire, extending it far beyond its previous territorial limits, deep into Central Asia, and engaging in a series of wars on the Korean Peninsula, first allying with Silla against Goguryeo, and then against Silla over the occupation of former Goguryeo territory. Within China, besides the more direct consequences of her struggle to gain and maintain power, Wu's leadership resulted in important effects regarding social class in Chinese society and in relation to state support for Taoism, Buddhism, education and literature.

Wu developed a network of spies to build a strong intelligence system in the court and throughout the empire, delivering daily reports on current affairs of the empire or opposition to the central state. She also played a key role in reforming the imperial examination system and encouraging capable officials to work in governance to maintain a peaceful and well-governed state. Effectively, these reforms improved her nation's bureaucracy by placing competence, rather than family connection, at the centre of the civil service. Wu also had a monumental impact upon the statuary of the Longmen Grottoes and the "Wordless Stele" at the Qianling Mausoleum, as well as the construction of some major buildings and bronze castings that no longer survive. Besides her career as a political leader, Wu also had an active family life. She was a mother of four sons, three of whom also carried the title of emperor, although one held that title only as a posthumous honor. One of her grandsons became the controversial Emperor Xuanzong of Tang, whose reign marked the turning point of the Tang dynasty into sharp decline.

Contents

Background and early life

The Wu family clan originated in Wenshui County, Bingzhou (an ancient name of the city of Taiyuan, Shanxi). Wu Zetian's birthplace is not documented in preserved historical literature and remains disputed. Some scholars argue that Wu was born in Wenshui, some that it was Lizhou (利州) (modern-day Guangyuan in Sichuan), while others insist she was born in the imperial capital of Chang'an (today known as Xi'an).

Wu Zetian was born in the seventh year of the reign of Emperor Gaozu of Tang. In the same year, a total eclipse of the sun was visible across China. Her father, Wu Shiyue, worked in the timber business and the family was relatively well off. Her mother was from the powerful Yang family. During the final years of Emperor Yang of Sui, Li Yuan (李淵) (who went on to become Emperor Gaozu of Tang) stayed in the Wu household many times and became close to the Wu family while holding appointments in both Hedong and Taiyuan. After Li Yuan overthrew Emperor Yang, he was generous to the Wu family, giving them money, grain, land, and clothing. Once the Tang dynasty became established, Wu Shihou held a succession of senior ministerial posts, including governor of Yangzhou, Lizhou, and Jingzhou (荊州) (modern-day Jiangling County, Hubei).

Wu was from a wealthy family, and was encouraged by her father to read books and pursue her education. He made sure that she was well-educated, an uncommon trait among women, much less encouraged by their fathers. Wu read and learned about many topics, such as politics and other governmental affairs, writing, literature, and music. At age 14, she was taken to be an imperial concubine (lesser wife) of Emperor Taizong of Tang. It was there that she became a type of secretary. This opportunity allowed her to continue to pursue her education. She was given the title of cairen, the title for one of the consorts with the fifth rank in Tang's nine-rank system for imperial officials, nobles, and consorts. When she was summoned to the palace, her mother, the Lady Yang, wept bitterly when saying farewell to her, but she responded, "How do you know that it is not my fortune to meet the Son of Heaven?" Lady Yang reportedly then understood her ambitions, and therefore stopped crying.

Consort Wu, however, did not appear to be much favored by Emperor Taizong. When Taizong died in 649, his youngest son, Li Zhi, whose mother was the main wife Wende, succeeded him as Emperor Gaozong.

Taizong had 14 sons, including three by his beloved Empress Zhangsun (601–636), but none with Consort Wu. Thus, according to the custom by which consorts of deceased emperors who had not produced children were permanently confined to a monastic institution after the emperor's death, Wu was consigned to Ganye Temple (感業寺) with the expectation that she would serve as a Buddhist nun there for the remainder of her life. But Wu defied expectations and left the convent for an alternative life. After Taizong's death, Li Zhi came to visit her and, finding her more beautiful, intelligent, and intriguing than before, decided to bring her back as his own concubine.

Empress consort

In 655, Wu became Tang Gaozong's new empress consort (皇后, húanghòu). Empress Wu was a powerful force in the world of politics, and had great influence over the Emperor.

In 656, Emperor Gaozong designated Empress Wu's son, Li Hong as the title of Prince of Dai and crown prince (that is, Heir Apparent). Soon after, Empress Wu became dominant at court, installing officials who favored her ascension in chancellor posts.

In 657, Empress Wu persuaded Emperor Gaozong to split the empire into two capitals and make Luoyang the capital alongside Chang'an. In 657, Empress Wu and her allies began reprisals against officials who had opposed her ascension.

In order to complete the social promotion of her family, she had the Wu clan listed among those of first importance in the registers of the "Great Families" (姓氏錄, xìngshìlù) by changing the "Book of Clans" to "Books of Names"; against imperial traditions. In late 659, she proposed to Emperor Gaozong that Palace Exam be opened to establish talented people from the lower classes as government officials. This reduced the power of the aristocracy. In 660, Li Zhong, Gaozong's first-born son (to consort Liu) also was targeted. Li Zhong had feared that he would be next and had sought out advice of fortune tellers. Wu had him exiled and placed under house arrest.

After removing those who opposed her rise, she had more power to influence politics, and Emperor Gaozong took full advantage of her advice on petitions made by officials and talking about state affairs.

In 660, Emperor Gaozong began to suffer from an illness that carried the symptoms of painful headaches and loss of vision, generally thought to be hypertension-related. He began to have Empress Wu make rulings on daily petitions and proposals made by officials. It was said that Empress Wu had quick reactions and understood both literature and history, and therefore, she made correct rulings, and Emperor Gaozong, with her ability, no longer paid much attention to governmental affairs, and over time and every day more and more depended on her advice, and delegated his duties to her. Thereafter, her authority rivaled Emperor Gaozong's. From this point on, Empress Wu became the undisputed power behind the throne until the end of his reign.

Over the years, Emperor Gaozong's illness had worsened, and Empress Wu's influence continued to grow and was fully established in the political arena. By 664, Empress Wu was said to be interfering so much in governance of the empire that she was angering Emperor Gaozong and was making him unhappy with her controlling behavior.

From January 665 until the end of his reign, Empress Wu would sit behind a pearl screen behind Emperor Gaozong at imperial meetings and she called her own orders "emperor edicts."; She even wore the yellow robe of the empire like an emperor, which was extraordinary and unprecedented for an empress, and Wu was effectively making the major and key decisions.

Although she had real power, Empress Wu was still in the background, and unsatisfied with her position, so took steps to increase the credibility of her power. In 674, one of her claims concerned the title of empress; she argued that because the emperor was called Son of Heaven (天子, Tiānzǐ), his wife should be called Heaven Empress (天后, Tiānhòu). As a result, she linked her rule with divine right. In 675, she succeeded in making her rule popular with the people with "twelve decrees" or "twelve proposals" for better governance and welfare of the people. In middle 675, as Emperor Gaozong's illness worsened, he considered having Wu formally rule as regent. The chancellor Hao Chujun and the official Li Yiyan both opposed this because Wu was already more powerful than Gaozong and they feared that she might take full possession of the throne. As a result, Gaozong did not formally make her regent, and Wu co-ruled with him as divine monarchs until his death in 683.

Before his death, at Wu's request, he ordered Li Zhe to come to Luoyang, and at her suggestion, handed over the imperial power to Li Zhe. Under her protection, Li Zhe took the throne (as Emperor Zhongzong), but Wu retained the real authority as empress dowager and regent.

Empress dowager

Upon the death of her husband Emperor Gaozong, Wu became empress dowager (皇太后, húangtàihòu) and then regent and she automatically gained full power over the empire. In the second month of 684, Li Zhe ascended to the imperial throne, known as his temple name Zhongzong, for a short six weeks.

The new emperor was married to a woman of the Wei family. Because Zhongzong was as weak and incompetent as his father, the new empress sought to place herself in the same position of great authority that Empress Wu had enjoyed. Empress Wei had seen that, Empress Wu had a tight grip on power and favors from Emperor Gaozong throughout the years and Wei wanted to be an uncontrollable and powerful empress consort like Wu.

Immediately, Emperor Zhongzong showed signs of disobeying Empress Dowager Wu. Emperor Zhongzong was under the thumb of his wife, Empress Wei. Under her influence, the Emperor, appointed his father-in-law as prime minister. He also tried to make his father-in-law Shizhong (侍中, the head of the examination bureau of government, 門下省, Menxia Sheng, and a post considered one for a chancellor) and gave a mid-level office to his wet nurse's son—despite stern opposition by the chancellor Pei Yan.

Pei reported this to Empress Dowager Wu, and she, after planning with Pei, Liu Yizhi, and the generals Cheng Wuting (程務挺) and Zhang Qianxu (張虔勖) deposed Emperor Zhongzong and replaced him with her youngest son Li Dan, the Prince of Yu (as Emperor Ruizong). Empress Dowager Wu had Zhongzong's father-in-law, Wei Xuanzhen (韋玄貞), brought up on charges of treason. Wei Xuanzhen was sent into seclusion. Emperor Zhongzong was reduced to the title of Prince of Luling and exiled. Empress Dowager Wu also sent the general, Qiu Shenji (丘神勣) to Li Xián's place in exile. As a result, Empress Dowager Wu used absolute power more strongly, centrally and violent than ever before.

Plenipotentiary regent for Emperor Ruizong

Wu had her youngest son Li Dan made emperor, known as his temple name Ruizong. She was the absolute ruler, however, both in substance and appearance. Wu did not even follow the customary pretense of hiding behind a screen or curtain and, in whispers, issued commands for the nominal ruler to formally announce, and so her reign was fully recognized. Ruizong never moved into the imperial quarters, appeared at no imperial function, and remained a virtual prisoner in the inner quarters. Although Emperor Ruizong held the title of emperor, Empress Dowager Wu firmly and exactly controlled the imperial court, and the officials were not allowed to meet with Emperor Ruizong, nor was he allowed to rule on matters of state, and she, not Emperor Ruizong, was the one that officials reported to, with Emperor Ruizong not even nominally approving official actions. Thus, all matters of empire were ruled on by Empress Dowager Wu. Soon after Emperor Ruizong took the throne, Empress Dowager Wu carried out a major renaming of governmental offices and banners. She, who disliked the capital Chang'an, also elevated Luoyang's status, making it a co-equal capital with Chang'an. At the suggestion of her nephew Wu Chengsi, she also expanded the ancestral shrine of the Wu ancestors and gave them greater posthumous honors, and made Wu's ancestral shrine the size of the emperors ancestral shrine.

Soon thereafter, Li Ji's grandson Li Jingye, the Duke of Ying, who had been disaffected by his own exile, started a rebellion at Yang Prefecture (揚州, roughly modern Yangzhou, Jiangsu). The rebellion initially drew much popular support in the region, however, Li Jingye progressed slowly in his attack and did not take advantage of that popular support. Meanwhile, Pei suggested to Empress Dowager Wu that she return imperial authority to the Emperor and argued that doing so would cause the rebellion to collapse on its own. This offended her, and she accused him of being complicit with Li Jingye and had him executed; she also demoted, exiled, and killed a number of officials who, when Pei was arrested, tried to speak on his behalf. She sent a general, Li Xiaoyi (李孝逸), to attack Li Jingye, and while Li Xiaoyi was initially unsuccessful, he pushed on at the urging of his assistant Wei Yuanzhong and eventually was able to crush Li Jingye's forces. Li Jingye fled and was killed in flight.

By 685, Empress Dowager Wu began to carry on an affair with the Buddhist monk Huaiyi and during the next few years, Huaiyi would be bestowed with progressively greater honors. In 686, Empress Dowager Wu offered to return imperial authorities to Emperor Ruizong, but Emperor Ruizong, knowing that she did not truly intend to do so, declined, and she continued to exercise imperial authority. Meanwhile, she installed copper mailboxes outside the imperial government buildings to encourage the people of the realm to report secretly on others, as she suspected many officials of opposing her, and also all the reports of betrayal were read by her personally. Thus, exploiting these beliefs of hers, secret police officials, including Suo Yuanli, Zhou Xing, and Lai Junchen, began to rise in power and to carry out systematic false accusations and executions of individuals.

In 688, Empress Dowager Wu was set to make sacrifices to the deity of the Luo River (洛水, flowing through the Henan province city of Luoyang, then the "Eastern Capital"). Wu summoned senior members of Tang's Li imperial clan to Luoyang. The imperial princes worried that she planned to slaughter them and secure the throne for herself: thus, they plotted to resist her. Before a rebellion could be comprehensively planned out, however, Li Zhen and his son Li Chong, the Prince of Langye rose first, at their respective posts as prefects of Yu Prefecture (豫州, roughly modern Zhumadian, Henan) and Bo Prefecture (博州, roughly modern Liaocheng, Shandong). The other princes were not yet ready, however, and did not rise, and forces sent by Empress Dowager Wu and the local forces crushed Li Chong and Li Zhen's forces quickly. Empress Dowager Wu took this opportunity to arrest Emperor Gaozong's granduncles Li Yuanjia (李元嘉) the Prince of Han, Li Lingkui (李靈夔) the Prince of Lu, and Princess Changle, as well as many other members of the Li clan. Even Princess Taiping's husband Xue Shao was implicated. In the subsequent years, there continued to be many politically motivated massacres of officials and Li clan members.

In 690, Wu took the final step to become the empress regnant of the newly proclaimed Zhou dynasty, and the title Huangdi. Traditional Chinese order of succession (akin to the Salic law in Europe) did not allow a woman to ascend the throne, but Wu Zetian was determined to quash the opposition and the use of the secret police did not subside, but continued, after her taking the throne. While her organization of the civil service system was criticized for its laxity of the promotion of officials, nonetheless, Wu Zetian was considered capable of evaluating the performance of the officials once they were in office. The Song dynasty historian Sima Guang, in his Zizhi Tongjian, commented:

Even though the Empress Dowager excessively used official titles to cause people to submit to her, if she saw that someone was incompetent, she would immediately depose or even execute him. She grasped the powers of punishment and award, controlled the state, and made her own judgments as to policy decisions. She was observant and had good judgment, so the talented people of the time also were willing to be used by her.

Reign as empress regnant

In 690, Wu had Emperor Ruizong yield the throne to her and established the Zhou dynasty, with herself as the imperial ruler (Huangdi).

Shortly after Wu took the throne in her newly established dynasty, she elevated the status of Buddhism above that of Taoism. She officially sanctioned Buddhism by building temples named Dayun Temple (大雲寺) in each prefecture belonging to the capital regions of the two capitals, Luoyang and Chang'an, and created nine senior monks as dukes. She enshrined seven generations of Wu ancestors at the imperial ancestral temple, while continuing to offer sacrifices to the Tang emperors Gaozu, Taizong, and Gaozong.

The early part of her reign was characterized by secret police terror, which moderated as the years went by. On the other hand, she was recognized as a capable and attentive ruler even by traditional historians who despised her, and her ability to select capable men to serve as officials was admired for the rest of the Tang dynasty as well as in subsequent dynasties.

Many of Wu's measures were popular and helped her to gain support for her rule. Wu came to power during a time in China in which the people were fairly contented, the administration was run well, and the economy was characterized by rising living standards. For the most part, as far as the masses were concerned, Wu continued in this manner. She was determined that free, self-sufficient farmers continue to work their own land, so she periodically used the juntian, equal-field system, together with updated census figures to ensure fair land allocations, reallocating as necessary. Much of her success was due to her various edicts (including those known as her "Acts of Grace"), which helped satisfy the needs of the lower classes through various acts of relief, her widening recruitment to government service to include previously excluded gentry and commoners, and her generous promotions and pay raises for the lower ranks.

Wu used her military and diplomatic skills to enhance her position. The fubing system of self-supportive soldier-farmer colonies, which provided local militia and labor services for her government, allowed her to maintain her armed forces at reduced expense. She also pursued a policy of military action to expand the empire to its furthest extent ever up to that point in Central Asia. Expansion efforts against Tibet and to the northwest, however, were less successful. In spring 696 she sent an army commanded by Wang Xiaojie and Lou Shide against the Tibetan Empire, which was soundly defeated by Tibetan generals, the brothers Gar Trinring Tsendro (論欽陵) and Gar Tsenba (論贊婆).

Wu Zetian utilized the imperial examination system to find talented poor people or people without backgrounds to stabilize her regime. People she promoted included Cui Xuanwei and Zhang Jiazhen.

In 699, Wu, realizing that she was growing old, feared that after her death, Li Xian and the Wu clan princes would not have peace with each other. She made him, Li Dan, Princess Taiping, Princess Taiping's second husband Wu Youji (a nephew of hers), the Prince of Ding, and other Wu clan princes to swear an oath to each other.

Reform of the imperial examination system

One apparatus of government that fell into Wu's power was the imperial examination system, the basic theory and practice of which was to recruit into government service those men who were the best educated, most talented, and had the best potential to perform their duties, and to do so by testing a pool of candidates to determine this. This pool was male only, and the qualified pool of candidates and resulting placements into official positions was on a relatively small scale at the time Wu took control of government. The official tests examined things considered important for functionaries of the highly developed, bureaucratic government structure of the imperial government, such as level of literacy in terms of reading and writing and possession of the specific knowledge considered necessary and desirable for a governmental official, such as Confucian precepts on the nature of virtue and theory on the proper ordering of and relationships within society. Wu continued to use the imperial examination system to recruit civil servants, and introduced major changes to the system she inherited, including increasing the pool of candidates permitted to take the test by allowing commoners and gentry, previously disqualified by their background, to take it. In 693, she expanded the governmental examination system and greatly increased the importance of this method of recruiting government officials. Wu provided increased opportunity for the representation within government to people of the North China Plain versus people of the northwestern aristocratic families (whom she decimated, anyway); and the successful candidates recruited through the examination system became an elite group within her government. The historical details of the consequences of Wu's promoting a new group of people from previously disenfranchised backgrounds into prominence as powerful governmental officials, and the examination system's role, remain debated by scholars of this subject.

Religion

The Great Cloud Sutra

Wu Zetian used her political powers to harness from Buddhist practices a strategy to build sovereignty and legitimacy to her throne while decisively establishing the Zhou dynasty in a society under Confucian and patriarchal ideals. One of the first steps she took to legitimize her ascension to the throne was to proclaim herself as the reincarnation of the Devi of Pure Radiance (Jingguang tiannü) through a series of prophecies. In 690, Wu sought out the support of the monk Xue Huaiyi, her reputed lover, and other nine orthodox Buddhist monks, to compose the apocryphal Commentary on the Meanings of the Prophecies About the Divine Sovereign in the Great Cloud Sutra (Dayunjing Shenhuang Shouji Yishu).

Translated from a late fourth-century version in Sanskrit to Chinese, the original Great Cloud Sutra (Dayunjing) accentuated in Wu's Commentary had fascicles describing a conversation between the Buddha and the Devi of Pure Radiance. In the sutra, the Buddha foretells to Jingguang that he would be a bodhisattva reincarnated in a woman's body in order to convert beings and rule over the territory of a country. Wu's Buddhist supporters meticulously propagated the Commentary "on the eve of her accession to the dragon throne" while seeking to justify the various events that led Wu to occupy the position of Huangdi as a female ruler and bodhisattva. Since gender in the Buddhist Devi worlds have no standard form, Wu later took a further step to transcend her gender limitations by identifying herself as the incarnation of two important male Buddhist divinities, Maitreya and Vairocana. Her narrative was intentionally crafted to persuade the Confucian establishment, circumvent the Five Impediments that restricted women from holding political and religious power, and gain public support.

Sacrifice on Mount Tai

In relation to Daoism, there are records that point to Wu's participation in important religious rituals, such as the tou long on Mount Song, and feng and shan on Mount Tai. One of the most important rituals was performed in 666. When Emperor Gaozong offered sacrifices to the deities of heaven and earth, Wu, in an unprecedented action, offered sacrifices after him, with Princess Dowager Yan, mother of Gaozong's brother Li Zhen, Prince of Yue, offering sacrifices after her. Wu's procession of ladies up Mount Tai conspicuously linked Wu with the Chinese empire's most sacred traditional rites. Another important performance was made in 700, when Wu conducted the tou long Daoist expiatory rite. Her participation in the rituals had political as well as religious motives. Such ceremonies served to consolidate Wu's life in politics and show she possessed the Mandate of Heaven.

Literature

North Gate Scholars

Toward the end of Gaozong's life, Wu began engaging a number of mid-level officials who had literary talent, including Yuan Wanqing (元萬頃), Liu Yizhi, Fan Lübing, Miao Chuke (苗楚客), Zhou Simao (周思茂), and Han Chubin (韓楚賓), to write a number of works on her behalf, including the Biographies of Notable Women (列女傳), Guidelines for Imperial Subjects (臣軌), and New Teachings for Official Staff Members (百僚新誡). Collectively, they became known as the "North Gate Scholars" (北門學士), because they served inside the palace, which was north of the imperial government buildings, and Wu sought advice from them to divert the powers of the chancellors.

The "Twelve Suggestions"

Around the new year 675, Wu submitted 12 suggestions. One was that the work of Laozi (whose family name was Li and to whom the Tang imperial clan traced its ancestry), Tao Te Ching, should be added to imperial university students' required reading. Another was that a three-year mourning period should be observed for a mother's death in all cases, not just in cases when the father was no longer alive. Emperor Gaozong praised her suggestions and adopted them.

Modified Chinese characters

In 690, Wu's cousin's son Zong Qinke submitted a number of modified Chinese characters intended to showcase Wu's greatness. She adopted them, and took one of the modified characters, Zhao (曌), to be her formal name (i.e., the name by which the people would exercise naming taboo on). 曌 was made from two other characters: Ming (明) on top, meaning "light" or "clarity", and Kong (空) on the bottom, meaning "sky". The implication appeared to be that she would be like the light shining from the sky. (Zhao (照), meaning "shine", from which 曌 was derived, might have been her original name, but evidence of that is inconclusive.) Later that year, after successive petition drives started by the low-level official Fu Youyi began to occur in waves, asking her to take the throne, Emperor Ruizong offered to take the name of Wu as well. On 18 August 690, she approved the requests. She changed the state's name to Zhou, claiming ancestry from the Zhou dynasty, and took the throne as Empress Regnant (with the title Empress Regnant Shengshen (聖神皇帝), literally "Divine and Sacred Emperor or Empress Regnant"). Ruizong was deposed and made crown prince with the atypical title Huangsi (皇嗣). This thus interrupted the Tang dynasty, and Wu became the first (and only) woman to reign over China as empress regnant.

Poetry

Wu's court was a focus of literary creativity. Forty-six of Wu's poems are collected in the Quan Tangshi (Collected Tang Poems) and 61 essays under her name are recorded in the Quan Tangwen (Collected Tang Essays). Many of those writings serve political ends, but there is one poem in which she laments her mother after she died and expresses her despair at not being able to see her again.

During Wu's reign, the imperial court produced various works of which she was a sponsor, such as the anthology of her court's poetry known as the Zhuying ji (Collection of Precious Glories), which contained poems by Cui Rong, Li Jiao, Zhang Yue, and others, arranged according to the poets' rank at court. Among the literary developments that took place during Wu's time (and partly at her court) was the final stylistic development of the "new style" poetry of the regulated verse (jintishi), by the poetic pair Song Zhiwen and Shen Quanqi.

Wu also patronized scholars by founding an institute to produce the Collection of Biographies of Famous Women. The development of what is considered characteristic Tang poetry is traditionally ascribed to Chen Zi'ang, one of Wu's ministers.

Removal and death

In autumn 704, accusations of corruption began to be levied against Zhang Yizhi and Zhang Changzong, as well as their brothers Zhang Changqi, Zhang Changyi, and Zhang Tongxiu (張同休). Zhang Tongxiu and Zhang Changyi were demoted, but even though the officials Li Chengjia (李承嘉) and Huan Yanfan advocated that Zhang Yizhi and Zhang Changzong be removed as well, Wu Zetian, taking the suggestion of the chancellor Yang Zaisi, did not do so. Subsequently, charges of corruption against Zhang Yizhi and Zhang Changzong were renewed by the chancellor Wei Anshi.

In winter 704, Wu Zetian became seriously ill for a period, and only the Zhang brothers were allowed to see her; the chancellors were not. This led to speculation that Zhang Yizhi and Zhang Changzong were plotting to take over the throne, and there were repeated accusations of treason. Once her condition improved, Cui Xuanwei advocated that only Li Xian and Li Dan be allowed to attend to her—a suggestion she did not accept. After further accusations against the Zhang brothers by Huan and Song Jing, Wu allowed Song to investigate, but before the investigation was completed, she issued a pardon for Zhang Yizhi, derailing Song's investigation.

By spring 705, Wu was seriously ill again. Zhang Jianzhi, Jing Hui, and Yuan Shuji planned a coup to kill the Zhang brothers. They convinced the generals Li Duozuo, Li Dan (李湛, note different character than the former emperor), and Yang Yuanyan (楊元琰) and another chancellor, Yao Yuanzhi, to be involved. With agreement from Li Xian as well, they acted on 20 February, killing Zhang Yizhi and Zhang Changzong, and had Changsheng Hall (長生殿), where Wu was residing, surrounded. They then reported to her that the Zhang brothers had been executed for treason, and forced her to yield the throne to Li Xian. On 21 February, an edict was issued in her name that made Li Xian regent, and on 22 February, an edict was issued in her name passing the throne to him. On 23 February, Li Xian formally retook the throne, and the next day, under heavy guard, Wu was moved to the subsidiary palace, Shangyang Palace (上陽宮), while still honored with the title of Empress Regent Zetian Dasheng (則天大聖皇帝). On 3 March, the Tang dynasty was restored, ending the Zhou.

Wu died on 16 December, and, pursuant to a final edict issued in her name, was no longer called empress regnant, but instead "Empress Consort Zetian Dasheng" (則天大聖皇后). In 706, Wu's son Emperor Zhongzong had Wu interred in a joint burial with his father, Emperor Gaozong, at the Qianling Mausoleum, near the capital Chang'an on Mount Liang. Zhongzong also buried at Qianling his brother Li Xián, son Li Chongrun, and daughter Li Xianhui (李仙蕙) the Lady Yongtai (posthumously honored as the Princess Yongtai)—victims of Wu's wrath.

Family

Modern depictions

Television

- Portrayed by Petrina Fung in the 1984 Hong-Kong TV series Empress Wu.

- Portrayed by Angela Pan in the 1985 Taiwanese TV series The Empress of the Dynasty.

- Portrayed by Liu Xiaoqing in the 1995 Chinese TV series Wu Zetian, in the 2007 TV series The Shadow of Empress Wu and in the 2011 TV series Secret History of Empress Wu.

- Portrayed by Gua Ah-leh in the 2000 Chinese TV series Palace of Desire.

- Portrayed by Qin Lan in the 2001 Chinese TV series Love Legend of the Tang Dynasty.

- Portrayed by Alyssa Chia in the 2003 Chinese TV series Lady Wu: The First Empress.

- Portrayed by Lü Zhong in the 2004 Chinese TV series Amazing Detective Di Renjie and its sequels Amazing Detective Di Renjie 2, Amazing Detective Di Renjie 3 and Mad Detective Di Renjie.

- Portrayed by Siqin Gaowa in the 2006 Chinese TV series Wu Zi Bei Ge.

- Portrayed by Yang Geum-seok in 2006–2007 KBS TV series Dae Jo Yeong.

- Portrayed by Rebecca Chan in the 2009 Chinese TV series The Greatness of a Hero.

- Portrayed by Yin Tao, Liu Xiaoqing and Siqin Gaowa in the 2011 Chinese TV series Secret History of Empress Wu.

- Portrayed by Wang Li Ke in the 2011 Chinese TV series Meng Hui Tang Chao.

- Portrayed by Kara Hui in the 2011 Chinese TV series Women of the Tang Dynasty and in the 2015 TV series Heroes of Sui and Tang Dynasties 5.

- Portrayed by Zhang Ting in the 2011 Chinese TV series Beauty World.

- Portrayed by Liu Yuxin in the 2012 Chinese TV series Secret History of Princess Taiping.

- Portrayed by Fan Bingbing in the 2014 Chinese TV series The Empress of China.

- Portrayed by Sheren Tang in the 2014 Chinese TV series Cosmetology High.

- Portrayed by Ruby Lin in the 2014 Chinese TV series Young Sherlock.

- Portrayed by Sophie Wu in the 2015 episode of Horrible Histories.

- Portrayed by Jiao Junyan in the 2017 Chinese TV series Legendary Di Renjie.

- Portrayed by Yong Mei in the 2021 Chinese TV series Luoyang.

Films

- Portrayed by Gu Lanjun in the 1939 Chinese movie The Empress Wu Tse-tien.

- Portrayed by Li Lihua in the 1963 Hong-Kong movie Empress Wu Tse-Tien.

- Portrayed by Carina Lau in the 2010 Chinese-Hong Kong movie Detective Dee and the Mystery of the Phantom Flame, its prequels Young Detective Dee: Rise of the Sea Dragon in 2013 and Detective Dee: The Four Heavenly Kings in 2018.

Video games

- Wu appears in the mobile game Fate/Grand Order as an Assassin class servant.

- Wu appears in the turn-based strategy games Civilization II, Civilization V and Civilization VI as a leader of the Chinese civilization.

- Wu appears as a character in the mobile game Law of Creation as a front-row tank.

- Wu appears as a minister earned in the mobile game Call Me Emperor after getting first place in the cross server intimacy event.

- Wu appears in the mobile game Rise Of Kingdoms as a legendary Chinese civilization Commander.

- Wu appears as the highest-paying symbol in Wu Zetian, a slot machine published by Realtime Gaming

Novels

- Wu is the protagonist, known as Mei, of the historically inspired fiction novel Moon in the Palace and its sequel The Empress of Bright Moon, both by Weina Dai Randel. Both are retellings of her life leading up to becoming Empress Wu.

- Xiran Jay Zhao's debut novel, Iron Widow, is a reimagining of Wu's life. In an interview with Publishers Weekly, Zhao said, "there's no other woman in Chinese history who had a rise through the harem as iconic as hers... It's been incredibly fun to reimagine her as instead a teenage peasant girl in an intensely misogynistic world who suddenly gains access to giant fighter mechas—how would she change her world?"

- Wu is the protagonist and narrator of Shan Sa's historical novel Impératrice, published in France in 2003. The novel, translated by Adriana Hunter, was published in English as Empress in 2006.

Images for kids

-

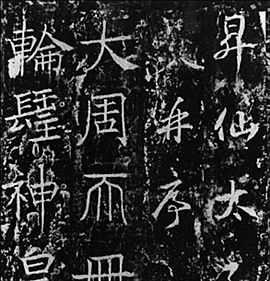

Epitaph for Yang Shun, general to Empress Wu Zetian, China, Luoyang, 693, limestone, Royal Ontario Museum

-

The Giant Wild Goose Pagoda, originally built in 652, it collapsed and was rebuilt in 701–704 during the reign of Wu Zetian; the present structure is largely the same as it was in the 8th century, although it used to be three stories taller before the damage caused by the 1556 Shaanxi earthquake

See also

In Spanish: Wu Zetian para niños

In Spanish: Wu Zetian para niños