Zelda Fitzgerald facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Zelda Fitzgerald

|

|

|---|---|

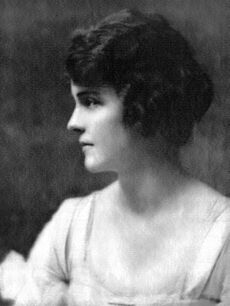

Fitzgerald in February 1920

|

|

| Born | Zelda Sayre July 24, 1900 Montgomery, Alabama, U.S. |

| Died | March 10, 1948 (aged 47) Asheville, North Carolina, U.S. |

| Occupation |

|

| Period | 1920–1948 |

| Spouse | |

| Children | Frances Scott Fitzgerald |

| Relatives | Anthony D. Sayre (father) |

| Signature | |

|

|

Zelda Fitzgerald (née Sayre; July 24, 1900 – March 10, 1948) was an American novelist, painter, playwright, and socialite. Born in Montgomery, Alabama, to a wealthy Southern family, she became locally famous for her beauty and high spirits. In 1920, she married writer F. Scott Fitzgerald after the popular success of his debut novel, This Side of Paradise. The novel catapulted the young couple into the public eye. After traveling abroad to Europe, Zelda's mental health deteriorated. Her doctors diagnosed Zelda with schizophrenia, although later posthumous diagnoses posit bipolar disorder.

While institutionalized at Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore, Maryland, she authored the 1932 novel Save Me the Waltz, a semi-autobiographical account of her early life in the American South during the Jim Crow era and her marriage to F. Scott Fitzgerald. Upon its publication by Scribner's, the novel garnered mostly negative reviews and experienced poor sales. The critical and commercial failure of Save Me the Waltz disappointed Zelda and led her to pursue her other interests as a playwright and a painter. In Fall 1932, she completed a stage play titled Scandalabra, but Broadway producers unanimously declined to produce the play. Disheartened, Zelda next attempted to paint watercolors but, when her husband arranged their exhibition in 1934, the critical response proved equally disappointing.

After her husband's death in December 1940, she attempted to write a second novel Caesar's Things, but she failed to complete the work. She died in a fire in Highland Hospital in Asheville, North Carolina in March 1948.

A 1970 biography by Nancy Milford was a finalist for the National Book Award. After the success of Milford's biography, scholars viewed Zelda's artistic output in a new light. Her novel Save Me the Waltz became the focus of literary studies exploring different facets of the work: how her novel contrasted with Scott's depiction of their marriage in Tender Is the Night, and how 1920s consumer culture placed mental stress on modern women. Concurrently, renewed interest began in Zelda's artwork, and her paintings were posthumously exhibited in the United States and Europe. In 1992, she was inducted into the Alabama Women's Hall of Fame.

Contents

Early life and family background

Born in Montgomery, Alabama, on July 24, 1900, Zelda Sayre was the youngest of six children. Her parents were Episcopalians. Her mother, Minerva Buckner "Minnie" Machen, named her daughter after the gypsy heroine in a novel, presumably Jane Howard's "Zelda: A Tale of the Massachusetts Colony" (1866) or Robert Edward Francillon's "Zelda's Fortune" (1874). Zelda was a spoiled child; her mother doted upon her daughter's every whim, but her father, Alabama politician Anthony Dickinson Sayre was a strict and remote man whom Zelda described as a "living fortress". Sayre was a state legislator in the post-Reconstruction era who authored the landmark 1893 Sayre Act which disenfranchised black Alabamians for seventy years and ushered in the racially segregated Jim Crow period in the state.

At the time of Zelda's birth, her family was a prominent and influential Southern clan who had been slave-holders before the Civil War. According to biographer Nancy Milford, "if there was a Confederate establishment in the Deep South, Zelda Sayre came from the heart of it". Zelda's maternal grandfather was Willis Benson Machen, a Confederate Senator and later an U.S. Senator from Kentucky. Her father's uncle was John Tyler Morgan, a Confederate general and the second Grand Dragon of the Ku Klux Klan in Alabama. Morgan played a key role in laying the foundation for the Jim Crow era in the American South. In addition to wielding considerable influence in national politics, Zelda's extended family owned the First White House of the Confederacy. According to biographer Sally Cline, "in Zelda's girlhood, ghosts of the late Confederacy drifted through the sleepy oak-lined streets," and Zelda claimed that she drew her strength from Montgomery's Confederate past.

During her idle youth in Montgomery, Zelda's affluent Southern family employed half-a-dozen domestic servants, many of whom were African-American. Consequently, Zelda was unaccustomed to domestic labor or responsibilities of any kind. As the privileged child of wealthy parents, she danced, took ballet lessons, and enjoyed the outdoors. In her youth, the family spent summers in Saluda, North Carolina, a village that would appear in her artwork decades later. In 1914, Zelda began attending Sidney Lanier High School. During high school, she continued her interest in ballet.

Courtship by F. Scott Fitzgerald

In July 1918, Zelda Sayre first met aspiring novelist F. Scott Fitzgerald at the Montgomery Country Club. At the time, Fitzgerald had been freshly rejected by his first love, Chicago socialite and heiress Ginevra King, due to his lack of financial prospects. Heartbroken by this rejection, Scott had dropped out of Princeton University and volunteered for the United States Army amid World War I. While awaiting deployment to the Western front, he was stationed at Camp Sheridan, outside Montgomery.

A lonely Fitzgerald began courting Zelda. Scott called Zelda daily, and he visited Montgomery on his free days. He often spoke of his ambition to become a famous novelist, and he sent her a chapter of a book he was writing. At the time, Zelda dismissed Fitzgerald's remarks as mere boastfulness, and she concluded that he would never become a famous writer. Infatuated with Zelda, Scott redrafted the character of Rosalind Connage in his unpublished manuscript The Romantic Egotist to resemble her, and he told Zelda that "the heroine does resemble you in more ways than four."

During the early months of their courtship, Zelda and Scott strolled through the Confederate Cemetery at Oakwood. While walking past the headstones, Fitzgerald ostensibly failed to show sufficient reverence, and Zelda informed Fitzgerald that he would never understand how she felt about the Confederate dead. Fitzgerald drew upon Zelda's intense feelings about the Confederacy and the Old South in his 1920 short story The Ice Palace about a Southern girl who becomes lost in an ice maze while visiting a northern town.

Scott's love for Zelda increased as time passed, and he wrote to his friend Isabelle Amorous: "I love her and that's the beginning and end of everything. You're still a Catholic, but Zelda's the only God I have left now." Ultimately, Zelda fell in love as well. Her biographer Nancy Milford wrote, "Scott had appealed to something in Zelda which no one before him had perceived: a romantic sense of self-importance which was kindred to his own."

Their courtship was interrupted in October when he was summoned north. He expected to be sent to France, but he was instead assigned to Camp Mills, Long Island. While he was there, the Allied Powers signed an armistice with Imperial Germany. He then returned to the base near Montgomery.

On February 14, 1919, he was discharged from the military and went north to establish himself in New York City. They wrote frequently, and by March 1920, Scott had sent Zelda his mother's ring, and the two had become engaged. However, when Scott's attempts to become a published author faltered during the next four months, Zelda became convinced that he could not support her accustomed lifestyle, and she broke off the engagement during the Red Summer of 1919.

Soon after, in July 1919, Fitzgerald returned to St. Paul. Having returned to his hometown as a failure, Fitzgerald became a social recluse and lived on the top floor of his parents' home at 599 Summit Avenue, on Cathedral Hill. He decided to make one last attempt to become a novelist and to stake everything on the success of a book. He worked day and night to revise The Romantic Egotist as This Side of Paradise—an autobiographical account of his Princeton years.

Marriage and celebrity

By September 1919, Scott completed his first novel, This Side of Paradise, and editor Maxwell Perkins of Charles Scribner's Sons accepted the manuscript for publication. Scott requested an accelerated release to renew Zelda's faith in him: "I have so many things dependent on its success—including of course a girl." After Scott informed Zelda of his novel's upcoming publication, a shocked Zelda replied apologetically: "I hate to say this, but I don't think I had much confidence in you at first.... It's so nice to know you really can do things do—anything—and I love to feel that maybe I can help just a little."

Zelda agreed to marry Scott once Scribner's published the novel; in turn, Fitzgerald promised to bring her to New York with "all the iridescence of the beginning of the world." Scribner's published This Side of Paradise on March 26, 1920, and Zelda arrived in New York on March 30. A few days later, on April 3, 1920, they married in a small ceremony at St. Patrick's Cathedral.

The early years of their marriage in New York City proved to be a disappointment. Despite the cooling of their affections, Scott and Zelda quickly became celebrities of New York.

The Fitzgeralds eventually moved to a cottage in Westport, Connecticut, where Scott worked on drafts of his second novel. Due to her privileged upbringing with many African-American servants, Zelda could not perform household responsibilities at Westport.

Soon after, Scott employed two maids and a laundress. Zelda's complete dependence upon servants became the comedic focus of magazine articles. When Harper & Brothers asked Zelda to contribute her favorite recipes in an article, she wrote: "See if there is any bacon, and if there is, ask the cook which pan to fry it in. Then ask if there are any eggs, and if so try and persuade the cook to poach two of them. It is better not to attempt toast, as it burns very easily. Also, in the case of bacon, do not turn the fire too high, or you will have to get out of the house for a week. Serve preferably on china plates, though gold or wood will do if handy."

While Scott attempted to write his next novel at their home in Westport, Zelda announced that she was homesick for the Deep South. In particular, she missed eating Southern cuisine such as peaches and biscuits for breakfast. She suggested that they travel to Montgomery, Alabama. On July 15, 1920, the couple traveled in a touring car—which Scott derogatorily nicknamed "the rolling junk"—to her parents' home in Montgomery. After visiting Zelda's family for several weeks, they abandoned the unreliable vehicle and returned via train to Westport, Connecticut. Zelda's parents visited their Westport cottage soon after, but her father Judge Anthony Sayre took a dim view of the couples' lifestyle. Following this visit, the Fitzgeralds relocated to an apartment at 38 West 59th Street in New York City.

Pregnancy and Scottie

In February 1921, while Scott labored on drafts of his inchoate second novel The Beautiful and Damned, Zelda discovered she was pregnant. She requested that the child be born on Southern soil in Alabama, but Fitzgerald adamantly refused. Zelda wrote despondently to a friend: "Scott's changed... He used... to say he loved the South, but now he wants to get as far away from it as he can." To Zelda's chagrin, her husband insisted upon having the baby at his northern home in Saint Paul, Minnesota. On October 26, 1921, she gave birth to Frances "Scottie" Fitzgerald.

While writing The Beautiful and Damned, Scott drew upon "bits and pieces" of Zelda's diary and letters. He modeled the characters of Anthony Patch on himself and Gloria Patch on—in his words—the chill-mindedness and selfishness of Zelda. Prior to publication, Zelda proofread the drafts, and she urged her husband to cut the cerebral ending which focused on the main characters' lost idealism. Upon its publication, Burton Rascoe, the newly appointed literary editor of the New York Tribune, approached Zelda for an opportunity to entice readers with a satirical review of Scott's latest work as a publicity stunt.

Although Zelda had carefully proofread drafts of the novel, she pretended in her review to read the novel for the very first time, and she wrote partly in jest that "on one page I recognized a portion of an old diary of mine... and, also, scraps of letters which, though considerably edited, sound to me vaguely familiar. In fact, Mr. Fitzgerald—I believe that is how he spells his name—seems to believe that plagiarism begins at home." In the same review, Zelda joked that she hoped her husband's novel would become a commercial success as "there is the cutest cloth of gold dress for only $300 in a store on Forty-second Street".

The satirical review led to Zelda receiving offers from other magazines to write stories and articles. According to their daughter, Scott "spent many hours editing the short stories she sold to College Humor and to Scribner's Magazine".

Following the financial failure of Scott's play The Vegetable, the Fitzgeralds found themselves mired in debt. Although Scott wrote short stories furiously to pay the bills, he became burned out and depressed. The couple departed in April 1924 for Paris, France, in the hope of living a more frugal existence abroad in Europe.

Expatriation to Europe

After arriving in Paris, the couple soon relocated to Antibes on the French Riviera. While Scott labored on drafts of The Great Gatsby, Zelda spent afternoons swimming at the beach and evenings dancing at the casinos.

Scott finalized The Great Gatsby in October 1924. The couple attempted to celebrate with travel to Rome and Capri, but both were unhappy and unhealthy. When he received the galleys for his novel, Scott fretted over the best title. After both Zelda and editor Max Perkins expressed their preference for The Great Gatsby, Fitzgerald agreed. It was also on this trip, while ill with colitis, that Zelda began painting artworks.

Meeting Ernest Hemingway

Returning to Paris in April 1925, Zelda met Ernest Hemingway, whose career her husband did much to promote. Through Hemingway, the Fitzgeralds were introduced to Gertrude Stein, Alice B. Toklas, Robert McAlmon, and others. Scott and Hemingway became close friends, but Zelda and Hemingway disliked each other from their first meeting.

Hemingway claimed that Zelda urged her husband to write lucrative short stories as opposed to novels in order to support her accustomed lifestyle. To supplement their income, Fitzgerald often wrote stories for magazines such as The Saturday Evening Post, Collier's Weekly, and Esquire. "I always felt a story in The Post was tops", Zelda later recalled, "But Scott couldn't stand to write them. He was completely cerebral, you know. All mind." Scott would write his stories in an 'authentic' manner, then rewrite them to add plot twists which increased their salability as magazine stories. After reading The Great Gatsby, Hemingway vowed to put any differences with Fitzgerald aside and to aid him in any way he could, although he feared Zelda would derail Fitzgerald's career.

In December 1926, after two unpleasant years in Europe which considerably strained their marriage, the Fitzgeralds returned to America, but their marital difficulties continued to fester.

Obsession and illness

Much of the conflict between the Fitzgeralds stemmed from the boredom and isolation Zelda experienced when Scott was writing. She would often interrupt him when he was working, and the two grew increasingly miserable. Stung by Fitzgerald's criticism that all great women use their talents constructively, Zelda had a deep desire to develop a talent that was entirely her own.

At the age of 28, she became obsessed with Russian ballet, and she decided to embark upon a career as a prima ballerina. Her friend Gerald Murphy counseled against their ambition and remarked that "there are limits to what a woman of Zelda's age can do and it was obvious that she had taken up the dance too late." Despite being far too old to achieve such an ambition, Scott Fitzgerald paid for Zelda to begin practicing under the tutelage of Catherine Littlefield, director of the Philadelphia Opera Ballet. After the Fitzgeralds returned to Europe in summer 1928, Scott paid for Zelda to study under Russian ballerina Lubov Egorova in Paris.

In September 1929, the San Carlo Opera Ballet Company in Naples invited her to join their ballet school. In preparation, Zelda undertook a grueling daily practice of up to eight hours a day, and she "punished her body in strenuous efforts to improve." According to Zelda's daughter, although Scott "greatly appreciated and encouraged his wife's unusual talents and ebullient imagination," he became alarmed when her "dancing became a twenty-four-hour preoccupation which was destroying her physical and mental health." Soon after, Zelda collapsed from physical and mental exhaustion.

Soon after her physical and mental collapse, Zelda's mental health further deteriorated. Zelda sought psychiatric treatment. After spending more than a year in various facilities, she returned home in September 1931. In an attempt to keep his wife out of an asylum, Scott hired nurses and attendants to care for Zelda at all times.

Save Me the Waltz

In February 1932, Zelda insisted that she be readmitted to a mental hospital. As part of her recovery routine, she spent at least two hours a day writing a manuscript. Toward the end of February 1932, Zelda shared fragments of her manuscript with Dr. Squires, who wrote to Scott that the unfinished novel was vivid and had charm. She sent the unaltered manuscript to Scott's editor, Maxwell Perkins, at Scribner's.

Surprised to receive an unannounced novel in the mail from Zelda, Perkins carefully perused the manuscript. He concluded the work had "a slightly deranged quality which gave him the impression that the author had difficulty in separating fiction from reality." He felt the manuscript contained several good sections, but its overall tone seemed hopelessly "dated" and tonally resembled Fitzgerald's 1922 work The Beautiful and Damned. Perkins hoped that her husband might be able to improve its overall quality with his criticism.

Upon learning that Zelda had submitted her manuscript to Perkins, Scott became angry that she had not shown her manuscript to him beforehand. After reading the manuscript, he objected to her novel's plagiarism of his protagonist in This Side of Paradise. He was further upset to learn that Zelda's novel used the very same plot elements as his upcoming novel, Tender Is the Night. After receiving letters from Scott delineating these objections, Zelda wrote to Scott apologetically that she was "afraid we might have touched the same material."

Despite Scott's initial annoyance, a debt-ridden Fitzgerald realized that Zelda's book might earn a tidy profit. Consequently, his requested revisions were "relatively few", and "the disagreement was quickly resolved, with Scott recommending the novel to Perkins." Several weeks later, Scott wrote to Perkins: "Here is Zelda's novel. It is a good novel now, perhaps a very good novel—I am too close to tell. It has the faults and virtues of a first novel.... It should interest the many thousands in dancing. It is about something and absolutely new, and should sell." Although unimpressed, Perkins agreed to publish the work as a way for Fitzgerald to repay his financial debt to Scribner's. Perkins arranged for half of Zelda's royalties to be applied against Scott's debt to Scribner's until at least $5,000 had been repaid.

On October 7, 1932, Scribner's published Save Me the Waltz with a printing of 3,010 copies—not unusually low for a first novel in the middle of the Great Depression—on cheap paper, with a cover of green linen. According to Zelda, the book derived its title from a Victor record catalog, and the title evoked the romantic glitter of the lifestyle which F. Scott Fitzgerald and herself experienced during the riotous Jazz Age. The parallels to the Fitzgeralds were obvious: The protagonist of the novel is Alabama Beggs—like Zelda, the daughter of a Southern judge—who marries David Knight, an aspiring painter who abruptly becomes famous for his work. They live the fast life in Connecticut before departing to live in France. Dissatisfied with her marriage, Alabama throws herself into ballet. Though told she has no chance, she perseveres and after three years becomes the lead dancer in an opera company. Alabama becomes ill from exhaustion, however, and the novel ends when they return to her family in the South, as her father is dying.

Echoing Zelda's frustrations, the novel portrays Alabama's struggle to establish herself independently of her husband and to earn respect for her own accomplishments. In contrast to Scott's unadorned prose, Zelda's writing style in Save Me the Waltz is replete with verbal flourishes and complex metaphors.

The reviews of Save Me the Waltz by literary critics were overwhelmingly negative.

Painting and later years

From the mid-1930s onward, Zelda would be hospitalized sporadically for the rest of her life at sanatoriums in Baltimore, New York, and in Asheville, North Carolina.

Despite the deterioration of her mental health, she continued pursuing her artistic ambitions. After the critical and commercial failure of Save Me the Waltz, she attempted to write a farcical stage play titled Scandalabra in Fall 1932. However, after submitting the manuscript to agent Harold Ober, Broadway producers rejected her play. Following this rejection, Scott arranged for her play Scandalabra to be staged by a Little Theater group in Baltimore, Maryland, and he sat through long hours of rehearsals of the play. Zelda also attempted to paint watercolors while in and out of sanatoriums.

In March 1934, Scott Fitzgerald arranged the first exhibition of Zelda's artwork—13 paintings and 15 drawings—in New York City. As with the tepid reception of her book, New York critics were ill-disposed towards her paintings. The New Yorker described them merely as "paintings by the almost mythical Zelda Fitzgerald; with whatever emotional overtones or associations may remain from the so-called Jazz Age." No actual description of the paintings was provided in the review.

In 1936, Scott placed her in the Highland Hospital in Asheville, North Carolina. Zelda remained in the hospital while Scott returned to Hollywood for a $1,000-a-week job with MGM in June 1937. For the next several years, Scott continued screenwriting on the West Coast and visiting a hospitalized Zelda on the East Coast. In April 1939, a coterie from Zelda's mental hospital had planned to go to Cuba, but Zelda had missed the trip. The Fitzgeralds decided to go on their own. The trip proved to be a disaster. The Fitzgeralds never saw each other again after the trip.

Scott returned to Hollywood in order to pay the ever-increasing bills for Zelda's continued hospitalization. She made some progress in Asheville, and in March 1940, four years after admittance, she was discharged to her mother's care. She was nearly forty now, her friends were long gone, and the Fitzgeralds no longer had much money. They wrote to each other frequently, and they made plans to meet again in December 1940. Their planned rendezvous did not occur due to Scott's death at 44 years of age in December 1940.

After Scott's death, Zelda read his unfinished manuscript titled The Love of the Last Tycoon. She wrote to his friend Edmund Wilson who agreed to edit the book and to eulogize his legacy. Zelda believed Scott's work contained "an American temperament grounded in belief in oneself and 'will-to-survive' that Scott's contemporaries had relinquished. Scott, she insisted, had not. His work possessed a vitality and stamina because of his indefatigable faith in himself." After reading The Last Tycoon, Zelda began work on a new novel, Caesar's Things. By August 1943, she returned to the Highland Hospital. She worked on her novel while checking in and out of the hospital. She did not get better, and she did not finish the novel.

Hospital fire and death

Towards the end of her life, Zelda resided in and out of sanatoriums. Zelda checked back into the hospital in September 1946, and then she returned to live with her mother Minnie in their Alabama home.

In November 1947, Zelda returned for the last time to Highland Hospital in Asheville, North Carolina. On the night of March 10, 1948, a fire broke out in the hospital kitchen. Nine women, including Zelda, died.

Zelda and Scott were buried in Rockville, Maryland, originally in Rockville Cemetery, away from his family plot. Only one photograph of the original gravesite is known to exist, taken in 1970 by Fitzgerald scholar Richard Anderson and published in 2016. At her daughter Scottie's request, Zelda and Scott were interred with the other Fitzgeralds at Saint Mary's Catholic Cemetery. Inscribed on their tombstone is the final sentence of The Great Gatsby: "So we beat on, boats against the current, borne back ceaselessly into the past."

Critical reappraisal

At the time of his third and fatal heart attack in December 1940, her husband Scott Fitzgerald died believing himself to be a failure as a writer. Two years later, after the United States' entrance into World War II, an association of publishing executives created the Council on Books in Wartime which distributed 155,000 copies of The Great Gatsby to U.S. soldiers overseas, and the book proved popular among beleaguered troops. By 1944, a full-scale Fitzgerald revival had occurred. Despite the renewed interest in Scott's oeuvre, Zelda's death in March 1948 was little noted in the press.

In 1950, acquaintance and screenwriter Budd Schulberg wrote The Disenchanted, with characters based recognizably on the Fitzgeralds who end up as forgotten former celebrities. It was followed in 1951 by Cornell University professor Arthur Mizener's The Far Side of Paradise, a biography of F. Scott Fitzgerald that rekindled interest in the couple among scholars. Mizener's biography was serialized in The Atlantic Monthly, and a story about the book appeared in Life magazine.

In 1970, however, the history of Zelda and Scott's marriage saw its most profound revision in a book by Nancy Milford, a graduate student at Columbia University. Zelda: A Biography, the first book-length treatment of Zelda's life, became a finalist for the National Book Award and figured for weeks on The New York Times best-seller list. The book recast Zelda as an artist in her own right whose talents were belittled by a controlling husband. Zelda posthumously became an icon of the feminist movement in the 1970s—a woman whose unappreciated potential had been suppressed by patriarchal society.

After the success of Milford's 1970 biography, scholars began to view Zelda's work in a new light. Prior to Milford's biography, scholar Matthew J. Bruccoli had written in 1968 that Zelda's novel Save Me the Waltz was "worth reading partly because anything that illuminates the career of F. Scott Fitzgerald is worth reading—and because it is the only published novel of a brave and talented woman who is remembered for her defeats." However, in the wake of Milford's biography, a new perspective emerged, and scholar Jacqueline Tavernier-Courbin wrote in 1979: "Save Me the Waltz is a moving and fascinating novel which should be read on its own terms equally as much as Tender Is the Night. It needs no other justification than its comparative excellence." After Milford's 1970 biography, Save Me the Waltz became the focus of many literary studies that explored different aspects of her work: how the novel contrasted with Scott's depiction of their marriage in Tender Is the Night, and how the consumer culture that emerged in the 1920s placed stress on modern women.

In 1991, Zelda's collected writings including Save Me the Waltz were edited by Matthew J. Bruccoli and published. Reviewing the collection, The New York Times literary critic Michiko Kakutani wrote "that the novel was written in two months is amazing. That for all its flaws it still manages to charm, amuse and move the reader is even more remarkable. Zelda Fitzgerald succeeded, in this novel, in conveying her own heroic desperation to succeed at something of her own, and she also managed to distinguish herself as a writer with, as Edmund Wilson once said of her husband, a 'gift for turning language into something iridescent and surprising.'"

In addition to a critical reappraisal of her novel, Zelda's artwork also has been reappraised as interesting in its own right. After spending much of the 1950s and 1960s in family attics—Zelda's mother even had much of the art burned because she disliked it—her work drew the renewed interest of scholars. Posthumous exhibitions of her watercolors have toured the United States and Europe. A review of the exhibition by curator Everl Adair noted the influence of Vincent van Gogh and Georgia O'Keeffe on her paintings and concluded that her surviving corpus of art "represents the work of a talented, visionary woman who rose above tremendous odds to create a fascinating body of work—one that inspires us to celebrate the life that might have been."

Scholars continue to debate the role that Zelda and Scott may have had in inspiring and stifling each other's creativity.

Zelda's daughter Scottie Fitzgerald insisted "that my father greatly appreciated and encouraged his wife's unusual talents and ebullient imagination. Not only did he arrange for the first showing of her paintings in New York in 1934 he sat through long hours of rehearsals of her one play, Scandalabra, staged by a Little Theater group in Baltimore; he spent many hours editing the short stories she told to College Humor and to Scribner's Magazine."

Legacy and influence

Zelda was the inspiration for "Witchy Woman", the song of enchantresses written by Don Henley and Bernie Leadon for the Eagles, after Henley read Zelda's biography; of the muse, the partial genius behind her husband F. Scott Fitzgerald, the wild, bewitching, mesmerizing, quintessential "flapper" of the Jazz Age.

Zelda's name served as inspiration for Princess Zelda, the eponymous character of The Legend of Zelda series of video games. In 1989, the F. Scott and Zelda Fitzgerald museum opened in Montgomery, Alabama. The museum is in a house they briefly rented in 1931 and 1932. It is one of the few places where some of Zelda's paintings are kept on display.

In 1992, Zelda and her daughter Scottie were posthumously inducted into the Alabama Women's Hall of Fame.

In 2023, Hatteras Sky and Lark Hotels planned three boutique hotels in Asheville, North Carolina, two of which will have Zelda Fitzgerald themes. Zelda Dearest, with 20 rooms, will have the "beauty and optimism" of Zelda's early life. Zelda Salon, named for Gertrude Stein's home in France, will have 35 rooms, with the design based on where the Fitzgeralds stayed in the 1920s.

See also

In Spanish: Zelda Fitzgerald para niños

In Spanish: Zelda Fitzgerald para niños