Wilmington insurrection of 1898 facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Wilmington massacre of 1898 |

|

|---|---|

| Part of the Nadir of American race relations | |

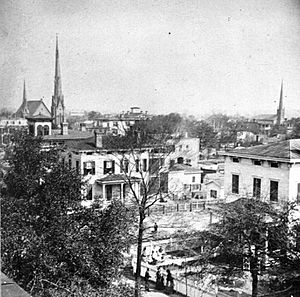

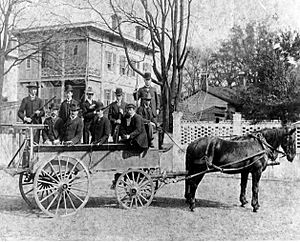

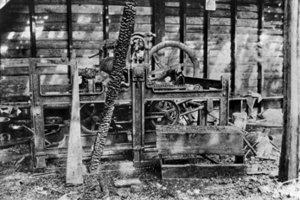

Mob posing by the ruins of The Daily Record

|

|

| Location | Wilmington, North Carolina |

| Date | November 10, 1898 |

| Target |

|

|

Attack type

|

|

| Weapons |

|

| Deaths | est. 14–300 black residents killed |

| Victims |

|

| Perpetrators |

|

|

Number of participants

|

2,000 |

| Motive |

|

|

Goals of Attack: (1) Government overthrow

(2) Maintenance of Antebellum Racial Hierarchy |

|

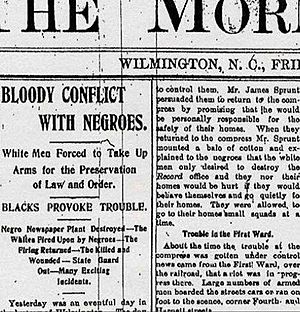

The Wilmington insurrection of 1898, also known as the Wilmington massacre of 1898 or the Wilmington coup of 1898, was a coup d'état and massacre carried out by white supremacists in Wilmington, North Carolina, United States, on Thursday, November 10, 1898. The white press in Wilmington originally described the event as a race riot caused by black people. Since the late 20th century and further study, the event has been characterized as a violent overthrow of a duly elected government by a group of white supremacists. It is the only such incident in the history of the United States.

The coup was the result of a group of the state's white Southern Democrats conspiring and leading a mob of 2,000 white men to overthrow the legitimately elected local Fusionist biracial government in Wilmington. They expelled opposition black and white political leaders from the city, destroyed the property and businesses of black citizens built up since the American Civil War, including the only black newspaper in the city, and killed an estimated 60 to more than 300 people.

The Wilmington coup is considered a turning point in post-Reconstruction North Carolina politics. It was part of an era of more severe racial segregation and effective disenfranchisement of African Americans throughout the South, which had been underway since the passage of a new constitution in Mississippi in 1890 which raised barriers to the registration of black voters. Other states soon passed similar laws. Historian Laura Edwards writes, "What happened in Wilmington became an affirmation of white supremacy not just in that one city, but in the South and in the nation as a whole", as it affirmed that invoking "whiteness" eclipsed the legal citizenship, individual rights, and equal protection under the law that black Americans were guaranteed under the Fourteenth Amendment.

Contents

Background

In 1860, just prior to the outbreak of the American Civil War, the majority of Wilmington's population was black, and it was also the largest city in the state of North Carolina, with a population of nearly 10,000. Numerous enslaved laborers and free people of color worked at the city's port, in households as domestic servants, and in a variety of jobs as artisans and skilled workers.

With the end of the war, freedmen who lived in many states left plantations and rural areas and moved to towns and cities, not only to seek work, but also to gain safety by creating black communities without white supervision. Tensions grew in Wilmington and other areas because of a shortage of supplies—Confederate currency suddenly had no value and the South was impoverished following the end of the long war.

In 1868, North Carolina ratified the Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution, resulting in the recognition of Reconstruction policies. The state legislature and governorship were dominated by Republican officials, with the governor a white man and the legislature made up of both white and black people. Freedmen were eager to vote and overwhelmingly supported the Republican Party that had emancipated them and given them citizenship and suffrage. However, conservative white Democrats, who had previously dominated politics in the state, greatly resented this "radical" change, which they deemed as being brought about by black residents, Unionist "carpetbaggers", and race traitors referred to as "scalawags".

Resentment also developed over Confederate veterans being barred from voting and holding public office in the state for a period after the war. Many white Democrats were already embittered by the Confederacy's defeat. Insurgent veterans joined the Ku Klux Klan (KKK), which orchestrated violence and intimidation to deter blacks from organizing and voting.

Democrats regained control of the state legislature in 1870. After the KKK was suppressed by the federal government through the Force Act of 1870, new paramilitary groups arose in the South. By 1874, chapters of Red Shirts, a paramilitary arm of the Democratic Party, had formed in North Carolina.

Democrats developed a plan to subvert home rule, seeking to have local officials appointed by the state rather than elected by the people. They began circumventing legislation by taking over the state's judiciary and adopting 30 amendments to the state constitution, which effected widespread policy changes, including lowering the number of judges on the North Carolina Supreme Court, putting the lower courts and local governments under the control of the state legislature, rescinding the votes of certain types of criminals, mandating segregated public schools, outlawing interracial relationships, and granting the General Assembly the power to modify or nullify any local government. By adopting these elements, the Democrats became identified as would-be bastions for white Americans. However, their control was largely limited to the western part of the state, within counties where, demographically, there were relatively few black Americans.

As the Democrats chipped away at Republican rule, things came to a head with the 1876 gubernatorial campaign of Zebulon B. Vance, a former Confederate soldier and governor. Vance called the Republican Party "begotten by a scalawag out of a mulatto and born in an outhouse." Through Vance, the Democrats saw their biggest opening to begin implementing their agenda in the eastern part of the state.

However, in that region, poor white cotton farmers were often more fed up with the capitalism of big banks and railroad companies, who charged high freight rates and used laissez-faire economics that worked against the already impoverished South. These farmers aligned with the labor movement, with many joining the People's Party (also known as the Populists). In 1892, as the U.S. plunged into an economic depression, the Populists banded with black Republicans who shared their hardships, forming an interracial coalition with a platform of self-governance, free public education, and equal voting rights for black men, called the Fusion coalition. Republicans and Populists agreed jointly to support municipal candidates.

Wilmington

In the last decade of the 19th century, Wilmington, still the largest city in the state, continued to have a majority-black population, with black people accounting for about 55 percent of its roughly 25,000 people. There were numerous black professionals and businessmen among them, and a rising middle class.

The Republican Party was biracial in membership. Unlike in many other jurisdictions, black people in Wilmington were elected to local office, and also gained prominent positions in the community. For example, three of the city's aldermen were black. Of the five members on the constituent board of audit and finance, one was black. Black people also served in the civic positions of justice of the peace, deputy clerk of court, and street superintendent, and as coroners, policemen, mail clerks, and mail carriers.

African Americans also held significant economic power in the city. Many former slaves had skills which they were able to use in the marketplace. For example, several became bakers, grocers, dyers, etc., making up nearly 35 percent of Wilmington's service positions.

By 1889, many black people had moved into other areas of the economy as well. They began moving out of service jobs and into other types of employment, where there was a higher demand for their work, along with higher pay. At the time, black people accounted for over 30 percent of Wilmington's skilled craftsmen, such as mechanics, carpenters, jewelers, watchmakers, painters, plasterers, plumbers, stevedores, blacksmiths, masons, and wheelwrights. In addition, they owned ten of the city's 11 restaurants, 90 percent of the city's 22 barbers, and one of the city's four fish and oyster dealerships. There were also more black bootmakers and shoemakers than white ones, one-third of the city's butchers were black, and half of the city's tailors were black. Lastly, two brothers, Alexander and Frank Manly, owned the Wilmington Daily Record, one of the few black newspapers in the state and reportedly the only black daily newspaper in the country.

With the help of patronage and equitable hiring practices, a few black people also held some of the most prominent business and leadership roles in the city, such as architect and financier Frederick C. Sadgwar. Thomas C. Miller was one of the city's three real estate agents and auctioneers, and was also the only pawnbroker in the city, with many whites known to be indebted to him. In 1897, following the election of Republican President William McKinley, John C. Dancy was appointed to replace a prominent white Democrat as the U.S. collector of customs at the Port of Wilmington, at a salary of nearly US$4,000 (equivalent to $140,704 in 2022). The editor of the Wilmington Messenger often disparaged him by referring to Dancy as "Sambo of the Customs House". Black professionals increasingly supported each other. For example, of the more than 2,000 black professionals in Wilmington at the time, more than 95 percent were clergy or teachers, professions where they were not shut out from competing, unlike doctors and lawyers.

White resentment

As black people in the area rapidly emerged into their newfound social status and progressed economically, socially, and politically, racial tensions grew. Former slaves and their children had no inherited wealth. With the collapse of the Freedman's Bank, which had a Wilmington branch, in 1874, some black residents of Wilmington lost most of their savings and as a result, many distrusted banks. The debt-slave metaphor, well-known within the community, made many residents wary of debt. In addition, credit or loans available to them were marked up in price. The annual interest rate of credit charged to black people was nearly 15 percent, compared to under 7.5 percent for poor whites, and lenders refused to let African-Americans pay off their mortgages in installments. This practice, known as "principal or nothing", positioned lenders to take over black property and businesses through forced sales. The lack of inherited wealth, limitations of access to credit, and loss of savings through federal mismanagement and fraud, created a combined effect in which black people "could not save anything", or otherwise acquire the means to own taxable property.

Though they made up nearly 60 percent of the county's population, property ownership among black residents in Wilmington was rare, at just eight percent. Of nearly $6 million in real and personal property taxes, they paid less than $400,000 of this amount. And while the per capita wealth for whites in the county was around US$550 (equivalent to $19,347 in 2022), it was less than US$30 (equivalent to $1,055 in 2022) for black people.

Despite this, affluent whites believed that they were paying taxes in a disproportionate amount given the amount of property they owned, relative to the city's black residents, who now held the political power to prevent affluent whites from changing this ratio. Additionally, there was tension with poor, unskilled whites, who competed with African-Americans in the job market and found their services in less demand than skilled black labor. Black people were caught between not meeting the expectations of affluent whites and exceeding the expectations of poor whites, paradoxically progressing too fast and too slow at the same time in the eyes of white residents.

The homes and businesses of successful African-Americans were sometimes torched by whites at night. But because black residents had enough economic and political power to defend their interests, socially, things were relatively peaceful.

Fusionist dominance

These dynamics continued with the elections of 1894 and 1896, in which the Republican-Populist Fusion ticket won every statewide office, including the governorship in the latter election, won by Daniel L. Russell. The Fusionists began dismantling the Democrats' political infrastructure, namely by reverting their appointed positions in local offices back to offices subject to popular elections. They also began trying to dismantle the Democratic stronghold in the less-populated western part of the state, which allowed the Democrats more political power through gerrymandering. The Fusionists also encouraged black citizens to vote, who constituted an estimated 120,000 Republican sympathizers.

By 1898, Wilmington's key political power was in the hands of "The Big Four", who were representative of the Fusion ticket: the mayor Dr. Silas P. Wright; the acting sheriff of New Hanover County, George Zadoc French; the postmaster, W. H. Chadbourn; and businessman Flaviel W. Fosters, who wielded substantial support and influence with black voters. The "Big Four" worked in concert with a circle of patrons—made up of about 2,000 black voters and about 150 whites—known as "the Ring". The Ring included about 20 prominent businessmen, about six first- and second-generation New Englanders from families that had settled in the Cape Fear region before the War, and influential black families such as the Sampsons and the Howes. The Ring wielded political power using patronage, monetary support, and an effective press through the Wilmington Post and The Daily Record.

This shift and consolidation of power horrified white Democrats, who contested the new laws, taking their grievances to the state Supreme Court, which did not rule in their favor. Defeated at the polls and in the courtroom, the Democrats, desperate to avoid another loss, became aware of discord between the Fusion alliance of black Republicans and white Populists, although it appeared that the Fusionists would sweep the upcoming elections of 1898, if voters voted on the following issues.

Issues

The economic issues, on which the Fusion coalition built its alliance, included:

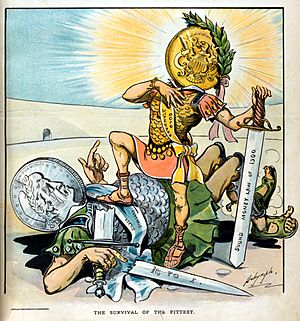

- Free coinage: Currency reform was an emotional issue, and the Fusionists built a pragmatic political coalition around it. The U.S. Coinage Act of 1834 had increased the silver-to-gold weight ratio from its 1792 level of 15:1 to 16:1, which brought the minting price for silver below its international market price, a move favorable to holders of silver bullion. In 1873, due to a change in market dynamics and currency circulation, the Treasury revised the law, abolishing the right of holders of silver bullion to have their metal struck into fully legal tender dollar coins, ending bimetallism in the United States and placing the nation firmly on the gold standard. Because of this, the act became contentious in later years, and it was denounced by people who wanted inflation as the "Crime of '73". The appearance of the revision was that it hurt poor people, as silver was known as "the poor man's money" given its use and circulation among the poor. While state Populist leadership believed its party was more ideologically aligned with the Democrats, some Populists refused to align with a party that did not support increased coinage of silver.

- 1868 North Carolina railroad bonds scandal: Since before the American Civil War, the state had been trying to expand the Western North Carolina Railroad, which was incorporated in 1855. The railroad, which was supposed to link Asheville to both Paint Rock, Alabama, and Ducktown, Tennessee, saw its construction stalled at Henry Station, a few miles from Old Fort, around 1872, plagued with construction problems in the Blue Ridge Mountains. The railroad became insolvent due to underfunding, misappropriation of bonds, and poor management. The state purchased the railroad in June 1875 for $825,000. However, the purchase also made the state liable for the railroad's nearly $45 million in debts—a substantial amount of that due to fraud because, in 1868, two men had defrauded the state legislature into issuing bonds for the railroad's western expansion. Controversy mounted when Zebulon Vance was re-elected as Governor in 1877 and made the railroad's completion a personal crusade. Vance had an inherent conflict of interest in supporting the railroad, as his family were major landholders in the area around Asheville, where the railroad would pass through. Additionally, although Vance publicly decried that the original bondholders were still owed money by the state, paying them would further cost the financially-strapped state, which would only further delay the construction of the railroad. Possibly because of this, Vance never took any action to resolve the crisis during the rest of his governorship, leaving many bondholders straddled with the debt of the state. Vance later left office to become a U.S. Senator, and after the railroad was completed using leased convict labor, he negotiated a sale of the railroad to a private company. After Vance left, the state issued a complete settlement of less than 15 percent of the roughly $45 million in bonds, leaving bondholders upset. Democrats blamed Republicans for the mishap, as they held legislative power when it happened. However, Fusionists associated railroads with the capitalist greed of Democrats. In addition, many of the Democrats blaming Republicans had voted to authorize the bonds, notably Tom Jarvis.

- Debt relief: Whites and blacks had differing experiences with debt after the American Civil War. For whites, before the war, being in debt invoked undertones of personal moral failings. However, after the war, the fact that most Southern whites were in debt created a sense of community. That community banded together to push for political and economic reforms and negotiate favorable interest rates. Conversely, black people deemed debt another form of slavery, one that was immoral, and sought to avoid it. They were often subject to high, non-negotiable interest rates. Recognizing that poor whites—who advocated doing away with credit systems altogether, in favor of a "pure-cash" system—had an incentive to keep debt low, and that poor black people were less well off than poor whites, Fusionists sought a platform to align their interests. By 1892, poor whites were incensed at Zebulon Vance and the Democrats, who had pledged to stand with the Farmers' Alliance (a precursor to the Populist party) on the issue of debt but had failed to do anything about the issue.

-

- With 90 percent of North Carolinians in debt, the Fusionist platform restricted interest rates to 6 percent. In 1895, once in office, the Fusionists successfully passed the measure with about 95 percent of black Republicans and white Populists supporting it; however, 86 percent of Democrats, who accounted for most of the lending class, opposed it.

1898 White Supremacy campaign

In late 1897, nine prominent Wilmington men were unhappy with what they considered black people's rule. They were particularly aggrieved about Fusion government reforms that affected their ability to manage and "game" (i.e., fix to their advantage) the city's affairs. Interest rates were lowered, which decreased banking revenue. Tax laws were adjusted, directly affecting stockholders and property owners who now had to pay a "like proportion" of taxes on the property they owned. Railroad regulations were tightened, making it more difficult for those who had railroad holdings to capitalize on them. Many Wilmington Democrats thought these reforms were directed at them, the city's economic leaders.

These men, the "Secret Nine" —Hugh MacRae, J. Allan Taylor, Hardy L. Fennell, W. A. Johnson, L. B. Sasser, William Gilchrist, P. B. Manning, E. S. Lathrop, and Walter L. Parsley—banded together and began conspiring to re-take control of the government.

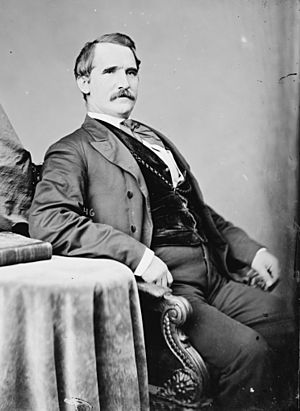

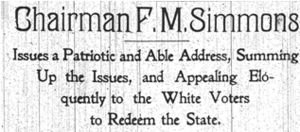

Around the same time, the newly elected Democratic State Party Chairman, Furnifold Simmons, was tasked with developing a strategy for the Democrats' 1898 campaign. Simmons knew that in order to win, he needed an issue that would cut across party lines. A student of Southern political history, he knew that racial resentment was easy to inflame.

Simmons then decided to build a campaign around the issue of white supremacy, knowing that the question would overwhelm all other issues. He began working with the Secret Nine, who volunteered to use their connections and funds to advance his efforts. He developed a strategy to recruit men who could "Write, Speak, and Ride." "Writers" were those who could create propaganda in the media; "speakers" were those who would be powerful orators; and "riders" were those who could ride a horse and be intimidating. He also had Tom Jarvis relay a promise to "the large corporations": if the Democrats won, the party would not raise their taxes.

In March 1898, Simmons met with Josephus "Jody" Daniels, the editor of the News & Observer, who also had the 21-year-old cartoonist Norman Jennett (nicknamed "Sampson Huckleberry") on staff, and with Charles Aycock. The men met at the Chatawka Hotel in New Bern and began planning how to execute the Democratic campaign strategy.

Simmons began by recruiting media outlets sympathetic to white supremacy, such as The Caucasian and The Progressive Farmer, which cynically called the Populists the "white man's party", while touting the party's alliance with black people. He also recruited aggressive, dynamic, and militant young white supremacists to help his effort. These publications presented black people as being "insolent", accused them of exhibiting ill-will and disrespect for whites in public, labeled them as corrupt and unjust, constantly laid claims about black men's alleged interest in white women, and accused white Fusionists allied with them of supporting blacks' "domination".

On November 20, 1897, following a Democratic Executive Committee meeting in Raleigh, the first statewide call for white unity was issued. Written by Francis D. Winston, it called on whites to unite and "re-establish Anglo-Saxon rule and honest government in North Carolina". He called Republican and Populist rule anarchy, evil, and apocalyptic, setting a vision for the Democrats to be the saviors—the redeemers—that would rescue the state from "tyranny".

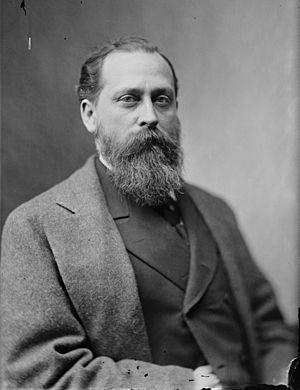

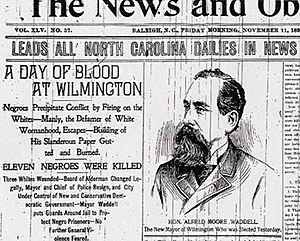

Alfred M. Waddell

Simmons created a speakers bureau, stacking it with talented orators whom he could deploy to deliver the message across the state. One of those orators was Alfred Moore Waddell, an aging member of Wilmington's upper class who was a skilled speaker and four-time former Congressman, losing his seat to Daniel L. Russell in 1878.

Waddell remained active after his defeat, becoming a highly sought-after political speaker and campaigner. He positioned himself as a representative of oppressed whites and a symbol of redemption for inflamed white voters. He had developed a reputation as "the silver tongued orator of the east" and as an "American Robespierre".

In 1898, Waddell, who was unemployed at the time, was also dealing with financial difficulty. His law practice was struggling, and his third wife, Gabrielle, largely supported him through her music teaching. The Chief of Police, John Melton, later testified that Waddell was seeking an opportunity to return to prominence as a politician, in order to "lighten the burden of his wife".

Waddell aligned with the Democrats and their campaign to "redeem North Carolina" from black's "domination". Melton stated that Waddell, who had been out of public life for while, saw the White Supremacy Campaign as "his opportunity to put himself before the people and pose as a patriot, thereby getting to the feed trough".

Waddell was "hired to attend elections and see that men voted correctly". With the aid of Daniels, who would distribute racist propaganda that he later acknowledged helped fuel a "reign of terror" (i.e., disparaging cartoons of blacks) before speeches, Waddell, and the other orators, began appealing to white men to join their cause.

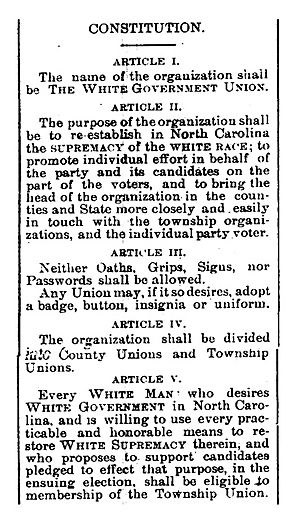

White Supremacy Clubs

As the fall of 1898 approached, prominent Democrats such as George Rountree, Francis Winston, and attorneys William B. McCoy, Iredell Meares, and John D. Bellamy, began organizing white supremacy clubs, known as the White Government Union. The clubs demanded that every white man in Wilmington join.

Many good people were marched from their homes ... taken to headquarters, and told to sign. Those that did not were notified that they must leave the city ... as there was plenty of rope in the city.

Membership in the clubs began spreading throughout the state. The clubs were complemented by the development of a white labor movement created to oppose blacks competing with whites for jobs. The "White Laborer's Union" got the backing of the Wilmington Chamber of Commerce and the Merchant's Association and vowed to create a "permanent labor bureau for the purpose of procuring white labor for employers".

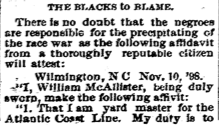

The efforts of the white supremacists finally consolidated in August 1898, when Alexander Manly, owner of Wilmington's only black newspaper, The Daily Record, wrote an editorial responding to a speech supporting lynchings where he spoke about the voluntary character of many relationships between white women and black men. Manly was the acknowledged grandson of Governor Charles Manly and his slave, Corinne. Whites were outraged at Manly's piece. This provided an opening for Democrats, now calling themselves "The White Man's Party", as "evidence" supporting their claims of predatory and emboldened blacks.

Commentaries

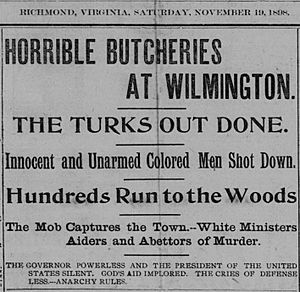

Within 48 hours, white supremacists, aided by newspapers across the South, used Manly's words—though reprinting incendiary distortions of them—as a championing catalyst for their cause.

Prior to this editorial, The Daily Record had been considered "a very creditable colored paper" throughout the state, that had attracted subscriptions and advertising from blacks and whites alike. However, after the editorial, white advertisers withdrew their support from the paper, crippling its income. Manly's landlord, M. J. Heyer, then evicted him. For his own safety, Manly was forced to relocate his press in the middle of the night. He and supporters moved his entire press from the corner of Water Street and Princess Street to a frame building on Seventh Street between Ann and Nun. He had planned to move to Love and Charity Hall (aka Ruth Hall), on South Seventh Street, but it declined to take him as a tenant because his presence would have greatly increased the building's insurance rate. Black pastors asked their congregations to step in and purchase subscriptions to help keep Manly's newspaper solvent, which many black women agreed to do, as they deemed Manly's paper to be the "one medium that has stood up for our rights when others have forsaken us."

John C. Dancy would later call Manly's editorial "the determining factor" of the riot.

Rallying the base

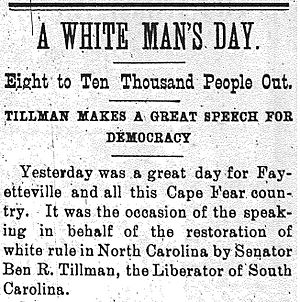

On October 20, 1898, in Fayetteville, the Democrats staged their largest political rally. The Red Shirts made their North Carolina debut, with 300 of them accompanying 22 "virtuous" young white ladies in a parade where cannons were fired and a brass band played. A guest of honor was South Carolina senator, Ben Tillman, who advocated a "shotgun policy" when it came to blacks.

Four days later, 50 of the city's most prominent white men, such as Robert Glenn, Thomas Jarvis, Cameron Morrison and Charles Aycock, who was now the pre-eminent orator of the campaign, packed the Thalian Hall opera house. Alfred Waddell delivered a speech, declaring that white supremacy was the only issue of importance for white men.

Portions of Waddell's speech were printed, sent around the state, and "quoted by speakers on every stump."

"White Supremacy Convention"

After the Thalian Hall speech, on October 28, "special trains from Wilmington" provided discounted train tickets to Waddell, and other white men, to travel across the state to Goldsboro for a "White Supremacy Convention". A crowd of 8,000 showed up to hear Waddell share the stage with Simmons, Charles Aycock, Thomas Jarvis, and Major William A. Guthrie and the mayor of Durham.

Waddell concluded his speech assuring them that white men would banish blacks, and their traitorous white allies, even if they had to fill the Cape Fear River with enough black dead bodies to block its passage to the sea.

Intimidation

Waddell's speech so inspired the crowd that the Red Shirts left the convention and started terrorizing black citizens and their white allies, in the eastern part of the state, right away. They destroyed property, ambushed citizens with weapon fire, and kidnapped people from their homes and whipped them at night, with the goal of terrorizing them to the point where Republican sympathizers would be too afraid to vote, or even register to do so.

The Democrats continued to put more pressure on Republican and Populist, leading to candidates being too afraid to speak in Wilmington.

Democrats sought to further capitalize on this fear by making efforts to suppress the Republican ticket in New Hanover County, arguing that a win by any political party opposing the Democrats would guarantee a race riot.

The Red Shirts, known to be "hot-headed," were looked down upon by the Wilmington white elite as "ruffians" and "low class". However, they deployed the Red Shirts around the city, who began holding a series of marches and rallies, organized by an unemployed sympathizer, Mike Dowling, an Irishman who, despite being the elected chair of the White Laborer's Union, had recently been fired as the foreman of Fire Engine Company Number 2 for incompetency and "continued insubordination."

On November 1, 1898, Dowling led a parade of 1,000 men, mounted on horses, for ten miles, through the black neighborhoods i.e. Brooklyn, of Wilmington. Joining his Red Shirts were the New Hanover County Horsemen and former members of the disbanded Rough Riders, led by Theodore Swann. White women waved flags and handkerchiefs as they passed. The procession ended at the First National Bank Building, which served as the Democratic Party headquarters, where they were encouraged by Democratic politicians in front of big crowds.

The next day, Dowling led a "White Man's Rally". Every "able-bodied" white man was armed. Escorted by Chief Marshal Roger Moore, a parade of men began downtown, again marched through black neighborhoods – firing into black homes and a black school on Campbell Square – and ended at Hilton Park where a 1,000 people greeted them with a picnic and free barbecue. A number of defiant speakers followed.

Leading up to the election, these gatherings became daily occurrences; the white newspapers announced the time and place of meetings. At night, the rallies took on a carnival-like atmosphere. However, away from the streets, the groups began disrupting black churches, and patrolling the streets as "White Citizens Patrols," wearing white handkerchiefs tied around their left arms, intimidating and attacking black citizens.

Atmosphere and suppression of black defense

The atmosphere in the city made blacks anxious and tense. Conversely, it made whites hysterical and paranoid.

A number of black men attempted to purchase guns and powder, as was legal, but the gun merchants, who were all white, refused to sell them any. The only weapons blacks had were a few old army muskets or pistols.

Newspapers incited people into believing that confrontation was inevitable. Rumors began to spread that blacks were purchasing guns and ammunition, readying themselves for a confrontation. Whites began to suspect black leaders were conspiring in churches.

The Political Director of The Washington Post, Henry L. West, went to Wilmington to cover the White Supremacy Campaign.

The Democrats hired two detectives to investigate the rumors, including one black detective. However, the detectives concluded that the black residents "were doing practically nothing". To prevent any black conspiring, the Democrats forbade blacks from congregating anywhere.

Right before the election, the Red Shirts, supported by the White Government Union, were told that they wanted the Democrats to win the election "at all hazards and by any means necessary ...". The Red Shirts had so instituted a level of fear among the city's blacks that, approaching the election, they were "in a state of terror amounting almost to distress".

1898 election

Most blacks and many Republicans did not vote in the November 8 election, hoping to avoid violence, as Red Shirts had blocked every road leading in and out of the city, and drove potential black voters away with gunfire.

Governor Russell, who by this point had withdrawn his name from the ballot in the county, decided to come to Wilmington, as it was his hometown, and he thought he might be able to calm the situation. However, when his train arrived, Red Shirts swarmed his train car and tried to lynch him.

When the day was over, Democrats won 6,000 votes, overall, which was sizable given that the Fusion Party won 5,000 votes just two years prior. However, years later, it was determined that the 11,000-vote net increase also strongly suggested a high degree of election fraud. Mike Dowling would support this suggestion when he testified that Democrat party officials worked with the Red Shirts, instructing them where to deposit Republican ballots so they could be replaced by votes for Democrats. The political director of the Washington Post, who was in Wilmington for the election, recounted, "No one for a moment supposes that this was the result of a free and untrammelled ballot; and a Democratic victory here, as in other parts of the State, was largely the result of the suppression..."

However, the biracial Fusionist government still remained in power in Wilmington, because the mayor and board of aldermen had not been up for reelection in 1898.

The night following the election, Democrats ordered white men to patrol the streets, expecting blacks to retaliate.

The White Declaration of Independence

The "Secret Nine" had charged Alfred Waddell's "Committee of Twenty-Five" with "directing the execution of the provisions of the resolutions" within a document that they authored, that called for the removal of voting rights for blacks and for the overthrow of the newly elected interracial government. The document was called "The White Declaration of Independence".

According to the Wilmington Messenger, the Committee of Twenty-Five included Hugh MacRae, James Ellis, Reverend J.W. Kramer, Frank Maunder, F.P. Skinner, C.L. Spencer, J. Allen Taylor, E.S. Lathrop, F. H. Fechtig, W.H. Northon Sr., A.B. Skelding, F.A. Montgomery, B.F. King, Reverend J.W.S. Harvey, Joseph R. Davis, Dr. W.C. Galloway, Joseph D. Smith, John E. Crow, F.H. Stedman, Gabe Holmes, Junius Davis, Iredell Meares, P.L. Bridgers, W.F. Robertson, and C.W. Worth.

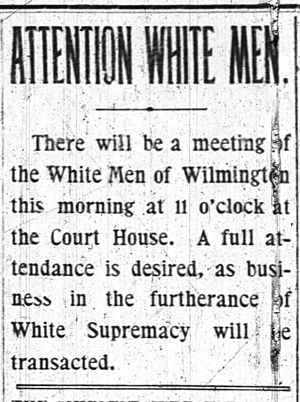

On election day, Hugh MacRae (of the Secret Nine) had the Wilmington Messenger call for a mass meeting. That evening, the paper published "Attention White Men", telling all white men to meet at the courthouse the following morning for "important" business.

On the morning of November 9, the courthouse was packed with 600 men of all professions and economic classes. Hugh MacRae sat in front with the former mayor, S.H. Fishblate, and other prominent white Democrats. When Alfred Waddell arrived, MacRae provided him a copy of "The White Declaration of Independence", which Waddell read to the crowd, "asserting the supremacy of the white man".

The crowd gave Waddell a standing ovation and 457 signed their names to adopt the proclamation, which would be published in the newspapers, without concealing who they were.

The group then decided to give the city's black residents 12 hours to comply with it. Alexander Manly had already shut his press down and left town when he was alerted, by a white friend, that the Red Shirts were going to lynch him that night. Manly's friend gave him $25 and told him a password to bypass white guards on Fulton Bridge, as bands of Red Shirts were patrolling the banks, trains, and steamboats. Once Manly, along with his brother Frank and two other fair-skinned black men, Jim Telfain and Owen Bailey, approached the guards, after escaping through the woods, the guards let them pass.

Waddell's Committee of Twenty-Five summoned the Committee of Colored Citizens (CCC), a group of 32 prominent black citizens, to the courthouse at 6:00 pm. They told the CCC of their ultimatum, instructing them to direct the rest of the city's black citizens to fall in line. When the black men asked to reason with them and pleaded that they could not control what Manly did, or what any other black person would do, Waddell responded that the "time had passed for words".

Lawyer Armond Scott wrote the letter and was instructed by the committee to personally deliver the response to Waddell's home, at Fifth and Princess Streets, by 7:30 a.m. the next day, November 10. Scott was afraid, and left the response in Waddell's mailbox. Scott later claimed that the letter Waddell had published in newspapers was not the letter he wrote. He said that the letter he authored expressed that Manly had ended publication of The Daily Record two weeks before the election, thereby eliminating the "alleged basis of conflict between the races".

Massacre and coup d'état

Alfred Waddell and the Committee of Twenty Five purportedly did not receive a response from the Wilmington Committee of Colored Citizens (CCC) by 7:30 a.m. on November 10, though it is unclear when Waddell checked his mailbox. As a result, about 45 minutes later, Waddell gathered about 500 white businessmen and veterans at Wilmington's armory. After heavily arming themselves with rifles and a Gatling gun, Waddell then led the group to the two-story publishing office of The Daily Record, the city's black-owned newspaper. They broke into editor Alexander Manly's building, vandalized the premises, set the building on fire, and gutted the remains. At the same time, black newspapers all over the state were also being destroyed. In addition, blacks, along with white Republicans, were denied entrance to city centers throughout the state.

Following the fire, the mob of white vigilantes swelled to about 2,000 men. A rumor circulated that some black people had fired on a small group of white men a mile away from the printing office. White men then went into black Wilmington neighborhoods, destroying black businesses and property and assaulting black inhabitants.

As Waddell led a group to disband and drive out the elected government of the city, the white mob rioted. Armed with shotguns, the mob attacked black people throughout Wilmington, but primarily in Brooklyn, the majority-black neighborhood.

The small patrols were spread out over the city and continued until nightfall. Walker Taylor was authorized by Governor Russell to command the Wilmington Light Infantry troops, just returned from the Spanish–American War, and the federal Naval Reserves, taking them into Brooklyn to quell the "riot". They intimidated both black and white crowds with weapons, shooting and killing several black men. Hundreds of black people fled the town to take shelter in nearby swamps.

As the violence spread, Waddell led a group to the Republican mayor, Silas P. Wright. Waddell forced Wright, the board of aldermen, and the police chief to resign at gunpoint. The mob installed a new city council that elected Waddell to take over as mayor by 4 p.m. that day.

Once he was declared mayor, the "Secret Nine" gave Waddell a list of prominent Republicans who he was to banish from the city. The next morning Waddell, flanked by George L. Morton and the Wilmington Light Infantry, marched six prominent black people on the list out of Wilmington; the other black people on the list had already fled. Waddell put them on a train headed north, in a special car with armed guards who were instructed to take them over the state line. Waddell then gathered the whites on the list and paraded them in front of a large crowd.

Aftermath

Wilmington

The number of Black people killed by the mob by the end of the day (November 10) is uncertain. Estimates have included "about 20," "more than twenty," "twenty or more," "somewhere between fourteen and sixty", "as many as 60," "at least sixty", "90,", "more than one hundred", and "exceeded 300.". An additional number, variously estimated between 20 and 50, were banished and ordered to leave town by the mob. The Rev. J.

While African Americans sought redress for the attacks at the federal level, many also blamed Manly for provoking the attacks by pushing white supremacists too far. John C. Dancy stated in a November 21 New York Times interview that Manly was responsible for the attacks, and that before his editorials the relations between blacks and whites were "most cordial and amicable ... but the white men of the South will not tolerate any reflection upon their women". Journalist and orator John Edward Bruce agreed, and spoke out against Manly's attempts to "revolutionize the social order". Even the National Afro-American Council called for a day of fasting for African Americans to offer "a hearty confession of our own sins", without condemning the role of white supremacists in the attacks.

Along with Alex and Frank G. Manly, brothers who had owned the Daily Record, more than 2,000 blacks left Wilmington permanently, forced to abandon their businesses and properties. This greatly reduced the city's professional and artisan class, and changed the formerly black-majority city into one with a white majority. While some whites were wounded, no whites were reported killed. City residents' appeals to President William McKinley for help to recover from the widespread destruction in Brooklyn received no response; the White House said it could not respond without a request from the governor, and Governor Russell had not requested any help. In the 6th District, Oliver Dockery contested John Bellamy's congressional seat in court. However, he did not prevail. While the loss of blacks and the refusal to hire black workers benefited the white labor movement in terms of job availability, white men were disappointed with the types of jobs that were available, as they were viewed as blacks' jobs that paid low wages. Subsequent to Waddell's usurping power, he and his team were re-elected in March 1899 to city offices. Waddell held the mayorship until 1905. He wrote his memoirs in 1907 and died in 1912.

| Name | Role | Aftermath of Coup Purveyors |

|---|---|---|

| Charles Aycock | Organizer | Became the 50th Governor of North Carolina. In 1900, he defended the mob violence as being justified to preserve the peace, saying, "This was not an act of rowdy or lawless men. It was the act of merchants, of manufacturers, of railroad men—an act in which every man worthy of the name joined. Ran for the U.S. Senate in 1912 against Furnifold Simmons, but died before the campaign was decided. Statues in his honor sit on Capitol Hill and at the North Carolina State Capitol. |

| John Bellamy | Orator | Became a North Carolina State Senator and a U.S. Congressman. |

| Josephus Daniels | News & Observer | Appointed Secretary of the Navy by President Woodrow Wilson during World War I. Became close friend of Franklin D. Roosevelt, who Daniels appointed as Assistant Secretary of the Navy. After Roosevelt became U.S. president, he returned the favor by appointing Daniels as Ambassador to Mexico between 1933 and 1941. In 1985, a statue was erected in his honor in Nash Square. The statue remained until 2020 when it was removed by his family in the wake of the murder of George Floyd. |

| Mike Dowling/Red Shirts | Red Shirts | Awarded one of 250 "special" police officer and firefighter positions. Dowling testified in Oliver Hockery's lawsuit challenging the validity of John Bellamy's election, revealing much about the coup's organization. |

| Rebecca Felton | Lynching supporter | Honored with appointment to the United States Senate. Became first woman to serve in the Senate, though she only served for one day. A prominent women's suffragist who championed equal pay for equal work. |

| Robert Broadnax Glenn | Orator | Became a North Carolina State Senator, then Governor of North Carolina and an ordained minister. |

| Tom Jarvis | Orator | Helped found East Carolina University, where the school's oldest residential hall is named in his honor. In Greenville, North Carolina, the United Methodist Church and a street are named in his honor. |

| Norman Jennett | Cartoonist | Thanked by Josephus Daniels for his cartoons for the campaign, with Daniels saying, "I do not know how we could have gotten along in the campaigns of 1896 and 1898 without Jennett's cartoons". Gifted US$63 (equivalent to $2,216 in 2022) by Democrats in appreciation for his "services in assisting in redeeming the state". Went on to work for the New York Herald and The Evening Telegram, and authored a comic strip, "The Monkey Shines of Marseleen". |

| Claude Kitchin | Orator | Longtime U.S. Congressman. Sat on the House Ways and Means Committee and chaired it for four years. Became House Majority Leader. |

| W.W. Kitchin | Leader | Served five more terms in Congress, then elected Governor of North Carolina. Led the 1900 approval of a state constitutional amendment to disenfranchise blacks. Attempted to prove blacks were unworthy of the Fourteenth Amendment. Identified in George Henry White's Congressional farewell address as the politician who had done the most to bring African Americans into "disrepute". |

| Walter L. Parsley | One of "The Secret Nine" | Owned the Hilton Lumber Co. and was a community leader near Masonboro Sound. In 1999, New Hanover County Schools purchased a 17.2-acre tract on Masoboro Loop Road for $785,000. Walter L. Parsley (the grandson of this Walter L. Parsley) owned the land with his wife Sarah B. Parsley. As a condition for purchasing the land, the New Hanover County Board of education requested the school be named Walter L. Parsley Elementary School “because of his generosity in making the land available to the community.” The reference included in the 1999 schedule of conditions may possibly be in reference to the seller, Parsley the grandson. Its mascot is the Patriots. |

| Hugh MacRae | One of "The Secret Nine" | Donated land outside Wilmington to New Hanover County for a "whites only" park, which was named for him. A plaque in his honor stands in the park, though it omits his role in the coup. Hugh MacRae Park, as it was known, had its name changed to Long Leaf Park in 2020. |

| Cameron Morrison | Orator | Became Governor of North Carolina. Was also a U.S. Senator and a U.S. Congressman. |

| George Rountree | WGU Sponsor | Became a North Carolina Assemblyman and sponsored legislation to keep blacks disenfranchised with a "Grandfather clause". Co-founder of the North Carolina Bar Association. |

| Furnifold Simmons | Campaign Manager | Became a U.S. senator and retained his seat for 30 years. Chairman of the Finance Committee for six years and ran, unsuccessfully, for president in 1920. |

| Ben Tillman | Orator | U.S. senator for nearly 25 years. Frequently ridiculed blacks on the floor of the U.S. Senate and boasted of having helped kill them during South Carolina's 1876 gubernatorial campaign. Has a building named in his honor at Clemson University. |

| Alfred Waddell | Orator; coup leader | Entered the 1900 U.S. North Carolina Senate race but withdrew, citing a family illness. Remained Mayor of Wilmington until 1905. Before he died in 1912, he was the keynote speaker at the unveiling of the Confederate monument at the Forsyth County Courthouse, where he was praised as a "gallant" soldier and proclaimed, "I thank God that monuments to the Confederate soldiers are rapidly multiplying in the land. I rejoice in the fact for many reasons, but chiefly because of its significance from one point-of-view". |

| Francis Winston | Campaign Manager | Charles Aycock appointed him Judge of the Superior Court for the Second Judicial District. Elected lieutenant governor. Served as United States Attorney for the Eastern District of North Carolina. |

State politics

Once installed in the state legislature, in 1899, Democrats, who had accounted for nearly 53 percent of the vote, determined there were two things they could do to retain their power:

- prevent blacks from voting, and

- normalize a racial hierarchy that allowed poor whites to feel empowered over, and antagonistic toward, blacks.

Disenfranchisement

To permanently install "good government by the White Man's Party", the "Secret Nine" installed George Rountree in the state legislature to ensure that blacks were kept from voting, and also to keep white Republicans from aligning, politically, with blacks again. On January 6, 1899, Francis Winston introduced a suffrage bill to keep blacks from voting. Rountree went on to chair a special joint committee overseeing the disenfranchisement amendment, a committee that existed to circumvent the U.S. Constitution which, in fact, granted blacks the right to vote.

The legislature passed a law requiring new voters to pay a poll tax, and passed a state constitutional amendment requiring prospective voters to demonstrate, to local elected officials, that they could read and write any section of the Constitution – practices that discriminated against poor whites, and more than 50,000 black men. However, to make sure that as few poor whites as possible would be hurt by the law, and prevented from voting Democrat, Rountree invoked a "Grandfather clause". The clause guaranteed the right to register and vote, bypassing the literacy requirement, if the voter, or a voter's lineal ancestor, was eligible to vote in his state of residence prior to January 1, 1867. This excluded practically any black man from voting.

The clause remained in effect until 1915, when the Supreme Court ruled it unconstitutional.

Ushering in "Jim Crow"

After the coup, the Democrats began to pass the state's first racial hierarchy laws, prohibiting blacks and whites from sitting together on trains, steamboats, and in courtrooms, and even requiring blacks and whites to use separate Bibles. Nearly every aspect of public life was codified to separate poor whites and blacks.

These laws, a direct result of the brief political alliance between blacks and poor whites, not only encouraged whites to see black people as outcasts and pariahs, but also rewarded them for doing so, socially and psychologically. This contributed to voluntary separation; prior to the insurrection, whites and blacks in Wilmington had lived close to one another, but over the following years, physical segregation increased between blacks and whites throughout the state, with home value, social status, and quality of life improving for whites the further they physically lived away from blacks. This served to lessen political democracy in the area, and enhance the oligarchical rule of the descendants of the former slaveholding class.

Through 1908, Democrats in other southern states began following North Carolina's example by suppressing the black vote, through disenfranchisement laws or constitutional amendments, of their own. They also passed laws mandating racial segregation of public facilities, and martial law-like impositions on African Americans. The US Supreme Court (at the time) upheld such measures.

Election of 1900

Two years after the coup, the Democrats again ran on the "domination" of blacks with disenfranchisement of blacks on the ballot. Gubernatorial candidate Charles Aycock (one of the campaign's orators) used what happened at Wilmington as a warning to those who dared to challenge the Democrats. He stated that disenfranchisement would keep the peace. When the votes in Wilmington were counted, only twenty-six people voted against black disenfranchisement, demonstrating the political effect of the coup.

| Year | Republican Vote | Democrat Vote | Populist Vote | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1896 | 154,025 | 145,286 | 30,943 | 330,254 |

| 1900 | 126,296 | 186,650 | 0 | 312,946 |

| 1904 | 79,505 | 128,761 | 0 | 208,266 |

Historical recounting

"Race riot"

On November 26, 1898, Collier's Weekly published an article in which Waddell wrote about the government overthrow. The article, "The Story of The Wilmington, North Carolina, Race Riots" included an early use of the term "race riot".

Despite vowing to "choke the Cape Fear River with carcasses", and the fact that some members of the white mob posed for a photograph in front of the charred remnants of The Daily Record, in the article Waddell painted himself as a reluctant, non-violent leader – or accidental hero – "called upon" to lead under "intolerable conditions". He painted the white mob not as murderous lawbreakers, but as peaceful, law-abiding citizens who simply wanted to restore law and order.

Although individuals of both races pointed to Democrat-backed violence as the driver behind the incident, the national narrative largely cast black men as aggressors, legitimizing the coup as a direct result of black aggression. For example, The Atlanta Constitution, a newspaper in Atlanta, Georgia, justified the violence as a rational defense of white honor, and a necessary response against the "criminal element of the blacks", furthering stereotypes of black violence.

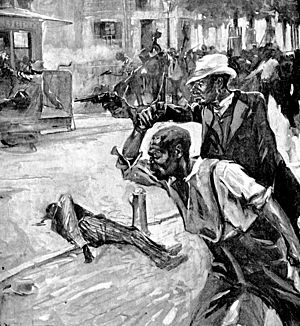

The complex reasons for the coup were overlooked in Waddell's account, which disregarded the overthrow as a carefully planned conspiracy, established the historical narrative as the coup being an event that "spontaneously happened", and helped usher in the Solid South. Complemented by Hugh Ditzler's illustration depicting blacks as gun-welding aggressors, Waddell and Ditzler effectively defined and illustrated the term "race riot", and set the precedent for its application which is still used today.

It was referred to that way by the North Carolina Legislature in 2000 when it set up the 1898 Wilmington Race Riot Commission, and is the term used to this day (2018) by the State Archives of North Carolina, North Carolina Department of Natural and Cultural Resources, and the State Library of North Carolina, in its online NCPedia.

"Massacre" vs. "Insurrection"

Waddell's Harper's Weekly account framed the violence, and the coup, with a "noble" narrative, comparing the events to the cause of the "Men of the Cape Fear" during the American Revolution. For many whites, the gallant framing remained, as the perpetrators of the coup were deemed to be "revolutionary" heroes who led an "insurrection" against a "riotous" black menace. For example, immediately, following the coup, the coup participants began reshaping the language of the events.

Conversely, the black survivors and community maintained that the event was a "massacre".

Revisionists dispute the white supremacist aspect of the event often by 1) denying the culpability of the white actors and 2) framing the cause of the white actors as noble.

Arguments that deny culpability, such as equating blame onto blacks, shifts blame away from the white actors and places it onto black residents and their white allies. "Noble" arguments stress that the white actors were not bad people, but honorable souls who were only fighting for "law and order". By not recognizing that the white actors sought "law and order" through criminality and violence, the goodness, valor and values of their ancestors remain affirmed.

The branding of the event as a "riot", "insurrection", "rebellion", "revolution", or "conflict", largely remained until the late 20th century due to the accounts of black survivors being minimized, ignored and omitted – as with The Daily Record destroyed, there were no media outlets to provide recorded accounts of blacks – and due to the South's adoption of Jubal Early's literary and cultural point of view of The Lost Cause, in which violence perpetuated by whites, across American Civil War, Reconstruction, and the Jim Crow era, evolved into a language of vindication and renewal.

The narrative of The Lost Cause allowed the North and the South to emotionally re-unify. It brought sentimentalism, by political argument, and recurrent celebrations, rituals and public monuments that allowed Southern whites to reconcile their regional pride with their Americanness. It also provided conservative traditions and a model of masculine devotion and courage in an age of gender anxieties and ruthless material striving. However, historians have argued that the reunion was of the North and the South was "exclusively a white man's phenomenon and the price of the reunion was the sacrifice of the African Americans".

A Gatling gun, and an armed mob, fired upon people prevented from arming themselves. However, the dissonance over the nomenclature of this fact, between blacks and whites, caused controversy about how to address its historical retelling, and also how to deal with the effects of the event's outcome.

1998 Centennial Commission

By the early 1990s, different groups in the city told and understood different histories of the events, sparking interest to discuss and commemorate the coup, following efforts to recognize similar atrocities in which white-led mobs destroyed the black communities, such as in Rosewood and Tulsa, respectively.

In 1995, informal conversations began among the African-American community, UNC-Wilmington's university faculty, and civil rights activists in order to educate residents about what really happened on that day, and to agree on a monument to memorialize the event. On November 10, 1996, the town of Wilmington held a program inviting the community to help make plans for the 1998 Centennial Commemoration. Over 200 people attended, including local state representatives and members of the city council. Some descendants of the white supremacy leaders of 1898 were opposed to any type of commemoration.

In early 1998, Wilmington planned a series of "Wilmington in Black and White" lectures, bringing in political leaders, academic specialists and civic rights activists, as well as facilitators such as Common Ground. George Rountree III attended a discussion held at St. Stephen's A.M.E. Church, attracting a large crowd, as his grandfather was one of the leaders of the 1898 violence. Rountree spoke of his personal support for racial equality, of his relationship with his grandfather, and of his refusal to apologize for his grandfather's actions as "the man was the product of his times". Other descendants of the coup's participants also said they owed no apologies, as they had no part in their ancestors' actions.

Many listeners argued with Rountree about his position and refusal to apologize. Some said that, "although he bore no responsibility for those events, he personally had benefited from them". Kenneth Davis, an African American, spoke of his own grandfather's achievements during those times, which Rountree's grandfather and others had "snuffed out" by their violence. Davis said that the "past of Wilmington's black community ... was not the past Rountree preferred".

1898 Wilmington Race Riot Commission

In 2000, the state legislature, recognizing that the black community had suffered severely, politically and economically, following the coup, especially due to state disenfranchisement and Jim Crow, created the 13-member, biracial, 1898 Wilmington Race Riot Commission to develop a historical record of the event and to assess the economic impact of the riot on blacks locally and across the region and state, co-chaired by state legislator Thomas E. Wright.

The Commission studied the riot for nearly six years, after hearing from numerous sources and scholars. The Commission produced a lengthy report on the event, authored by state archivist LeRae Umfleet, finding that the violence was "part of a statewide effort to put white supremacist Democrats in office and stem the political advances of black citizens." Harper Peterson, former mayor of Wilmington and a member of the commission, said "Essentially, it crippled a segment of our population that hasn't recovered in 107 years." According to Umfleet, "'massacre', rather than 'riot', does apply. That's a big, strong word, but that's what it was."

The commission made broad recommendations for reparations by government and businesses that would benefit not only African-American descendants, but also the entire community. The Commission recommended 10 bills to the North Carolina Legislature, to correct the century-old damage with reparations for victims' descendants through economic and business development, scholarships, and other programs. The Legislature did not pass any of them.

Historians noted that the Raleigh News & Observer had contributed to the riots by publishing inflammatory stories, in addition to the results of the elections in Wilmington. This encouraged white men from other parts of the state to travel to Wilmington, to take part in the attacks against blacks, including the coup d'état. Articles in the Charlotte Observer have also been cited as adding to the inflamed emotions. The Commission asked the newspapers to make scholarships available to minority students and to help distribute copies of the commission report. The commission "also asked that New Hanover County, which includes the city, be placed under special federal supervision through the Voting Rights Act", to ensure that current voter registration and voting are conducted without discrimination.

Reply from League of the South

In 2005, the League of the South, a white supremacist group "known for opposing civil rights laws and defending the right to display the Confederate flag", set up a web site, "1898 Wilmington". Under the name of "1898 Wilmington Institute for Education & Research", they spoke of "Reconstruction horror". What is "sometimes labeled a race riot or rebellion" was actually the actions of law-abiding white Democrats rescuing the city from Republican and carpetbagger corruption, compounded by ignorant, misled blacks who were in no way capable of voting intelligently. They quoted white supremacist governor Charles Aycock, who was "passionately interested in good government": "[T]he only hope of good government in North Carolina, and the other Southern States, rested upon the assured political supremacy of the white race". It quotes approvingly the pro-lynching spokeswoman Rebecca Felton, claims that blacks did not lose any property as a result of the riot, and blames the entire conflict on Alexander Manly, carpetbaggers, and other Republicans.

Commemorations

Several commemorations of the event have taken place:

- Former Star-News reporter, Harry Hayden, released a romanticized accounting of the overthrow in his 1936 pamphlet, The Story of the Wilmington Rebellion, in which he rebranded the event a "Revolution" that had saved North Carolina from Reconstruction. Conversely, Helen G. Edmonds addressed the riot in 1951, writing: "In reality, the Democrats effected a coup d'etat." As the predominant view of the time reflected the Dunning School's disparagement of Reconstruction, and white historians commonly referred to the events as a "race riot", equally attributing blame to blacks, Edmonds assessment of the events was overlooked by many.

- In November 2006, the News and Observer, deeming the coup as being "a giant shadow hanging over it", issued a Special Feature fully acknowledging its role as a leader in that coup's propaganda effort under Josephus Daniels.

- In January 2007, the North Carolina Democratic Party officially acknowledged and renounced the actions by party leaders during the Wilmington insurrection and the white supremacy campaigns.

- In April 2007 Representatives Wright, Jones and Harrell introduced House Bill #1558, the "1898 Wilmington Riot Reconciliation Act", into the North Carolina General Assembly. The Act would allow the estates of those injured, killed, or who suffered personal or property losses, resulting from the events on November 10 to file a lawsuit against the city for redress. The loss would have to be valued and, any payout would be adjusted by 8 percent for inflation. The Bill never advanced beyond its introduction.

- In August 2007, the state senate passed a resolution acknowledging and expressing "profound regret" for the riot.

- In 2007, some advocates lobbied to get the coup covered in the state's school curriculum, while historians have sought to build a memorial at the corner of Third and Davis Streets in Wilmington to commemorate the incident.

- In January 2017, two Wilmington writers, John Jeremiah Sullivan and Joel Finsel, backed by the creative writing department at UNCW, began working with middle school students, at Williston School and the Friends School of Wilmington, to locate, salvage and transcribe copies of The Daily Record. After the newspaper was destroyed, W.H. Bernard, the [then] editor of the Wilmington Morning Star, offered to purchase any outstanding copies of The Daily Record for 25 cents each. After six months, the group located eight pages; however, only seven of those pages are legible. The pages will eventually be available through the Library of Congress' "Chronicling America" digital series, and through the Digital Heritage Center's public website.

- In January 2018, North Carolina's Highway Historical Marker Committee approved the installation of a plaque to commemorate the event. The plaque will be installed in March 2018, on Market Street between Fourth Street and Fifth Street, which is the location of the Light Infantry Building, where the rioting began.

In media

- Charles W. Chesnutt's novel, The Marrow of Tradition (1901), addressed the rise of white supremacists in North Carolina and described a fictional account of a riot in a city based on Wilmington; it was more accurate than contemporary portrayals by Southern white newspapers. He portrayed the riots as initiated in white violence against blacks, with extensive damage suffered by the black community.

- In The Leopard's Spots (1902), North Carolina author Thomas Dixon Jr. (who wrote “The Clansman” upon which the 1915 film “The Birth of a Nation" was based), historicizes in considerable detail the 1898 white supremacy campaign and Wilmington massacre."

- Wilmington author Philip Gerard wrote a novel, Cape Fear Rising (1994), that recounts the 1898 campaign and events leading to the burning of the Daily Record.

- John Sayles portrayed the Wilmington Insurrection in Book Two of his novel, A Moment in the Sun (2011), based on contemporary primary sources. Sayles combines fictional characters with historical figures.

- David Bryant Fulton, writing under the name Jack Thorne, wrote the novel Hanover; or, The Persecution of the Lowly. A Story of the Wilmington Massacre (2009).

- Barbara Wright's young adult novel, Crow (2012), portrays the events through a fictional young African-American boy, the son of a reporter on the black newspaper. Her work was named a Notable Social Studies Trade Book in 2013 by the National Council for the Social Studies.

- A documentary film about the Wilmington insurrection, Wilmington on Fire, was released in 2016. It was directed by Christopher Everett.

- David Zucchino won the 2021 Pulitzer Prize for General Nonfiction for Wilmington's Lie: The Murderous Coup of 1898 and the Rise of White Supremacy (2020). The book uses contemporary newspaper accounts, diaries, letters and official communications to create a narrative that weaves together individual stories of hate and fear and brutality.

- In the 2021 episode of the Criminal podcast titled "If it ever happens, run," host Phoebe Judge tells the story of the Wilmington insurrection through a combination of narrative and interviews.

- The November 2, 2022 episode of the BBC World Service’s “Sounds” discussed the Wilmington Insurrection and its impact on Black fiddler Frank Johnson.

See also

- January 6 United States Capitol attack

- Attempts to overturn the 2020 United States presidential election

- Business Plot

- Cary's Rebellion

- Colfax Massacre

- Domestic terrorism in the United States

- Election Riot of 1874

- Jaybird–Woodpecker War

- List of attacks on legislatures

- List of coups and coup attempts by country#United States

- List of expulsions of African Americans

- Red Summer (1919)

- White backlash

Images for kids

-

Rebecca L. Felton, who gave an August 11, 1898 speech supporting lynching (image c. 1910)

-

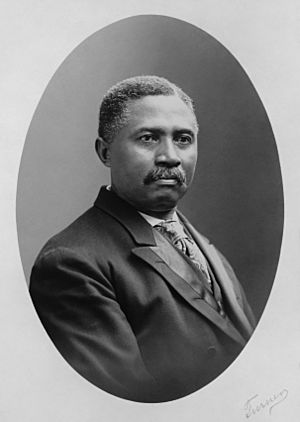

Alexander Manly, who as editor of The Wilmington Daily Record wrote a rebuttal editorial on August 18, 1898 (image c.1880s)

-

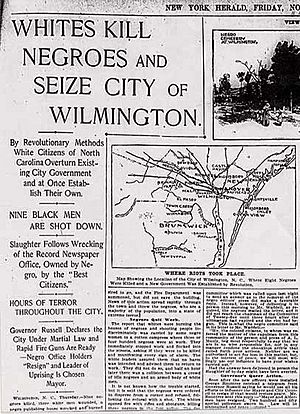

Reprint of Alexander Manly's August 18, 1898 Daily Record rebuttal editorial defending interracial relationships. Manly's editorial was used as a pretext for the insurrection in November.