William Brattle facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

William Brattle

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Massachusetts Attorney General | |

| In office 1736–1738 |

|

| Monarch | George II |

| Preceded by | John Overing |

| Succeeded by | Edmund Trowbridge |

| Personal details | |

| Born | April 18, 1706 Cambridge, Massachusetts |

| Died | October 25, 1776 (aged 70) Halifax, Nova Scotia |

| Spouses | Katherine Saltonstall (m. 1727) Martha Fitch (m. 1752) |

| Children | 9, including Thomas and Katherine |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | (1729–1776) |

| Branch/service | (1729–1776) |

| Rank | Major-General |

| Unit | 1st Regiment of Militia of Middlesex |

| Battles/wars | King George's War French and Indian War |

Major-General William Brattle (April 18, 1706 – October 25, 1776) was an American politician, lawyer, cleric, physician and military officer who served as the Attorney General of Massachusetts from 1736 to 1738. Brattle is best known for his role during the American Revolution, in which he initially aligned himself with the Patriot cause before shifting his allegiances towards the Loyalist camp, which led to the eventual downfall of his fortunes.

The son of a prominent Massachusetts cleric, Brattle graduated from Harvard College in 1722 and soon inherited the estates of both his father and uncle, making him one of the wealthiest men in Massachusetts. Brattle dabbled in medicine and law before spending the majority of his career as a politician and military officer in the colonial militia, serving through two French and Indian Wars and rising to the rank of brigadier-general by 1760.

When tensions increased between Great Britain and its North American colonies, Brattle initially favored the Patriots before joining the Loyalist camp after a disagreement over judges' salaries. In 1774, Brattle wrote a letter to Governor Thomas Gage about the state of a gunpowder magazine outside Boston; rising tensions led Gage to order the gunpowder there to be relocated, infuriating local residents who forced Brattle to seek British protection.

Brattle remained in British-controlled Boston during the outbreak of the American Revolutionary War, including when it was placed under siege by Patriot troops in 1776. He left alongside the British Army when they evacuated the city in March 1776, settling down in the city of Halifax, Nova Scotia, where Brattle died seven months later at the age of 70. Brattle Street in Cambridge and the town of Brattleboro, Vermont, are named in his honor.

Contents

Early life

William Brattle was born on April 18, 1706, in Cambridge, Massachusetts. His father, The Rev. William Brattle, was a Congregational cleric who served as the minister of the First Parish in Cambridge from 1696 to 1717; he was also a Harvard College graduate, a fellow of the Royal Society, and a slaveholder. Brattle's mother was Elizabeth Hayman Brattle, who died on July 28, 1715. He had an older brother, Thomas, who died young.

His father died in 1717, and the next year the young William began attending Harvard College. During his time there, he entered the college at the head of his class, which included Richard Saltonstall (of the prominent Saltonstall family) and future Rhode Island politician and merchant William Ellery Sr.; he was also fined for violating Harvard's rules. After six years, Brattle graduated from Harvard in 1722 with a Bachelor of Arts degree.

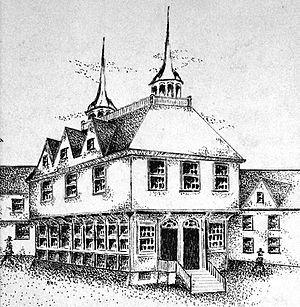

In 1727, at the age of 21, Brattle, as the sole heir both of his father and Brattle's uncle Thomas inherited their estates, which made him one of the wealthiest men in all of Massachusetts. At this point in his life, Brattle had "inherited a large and well invested property, and had ample means to cultivate those tastes to which, by his nature and education, he was inclined". In the same year, he ordered the construction of a large mansion.

Career in Massachusetts

After he had graduated from Harvard, Brattle briefly became a cleric and started to give sermons. However, by 1725 he had decided he was no longer interested in continuing to pursue the ministry and began to practice medicine, providing treatment during his time in Cambridge to both residents and college students. He also operated a private law practice and, "particularly dedicated to his alma mater", sat on the Harvard Board of Overseers.

In 1729, Brattle served as a selectman on the Cambridge board of selectmen, the executive arm of the town's local government; he would go on to serve as a selectman 21 times. On 1736, he was elected as a representative into the House of Assembly of Massachusetts Bay. In the same year, Brattle also began serving as the Massachusetts Attorney General, a position which he retained until 1738, when Edmund Trowbridge succeeded him.

His family connections placed him among the Massachusetts elite, and Brattle soon became involved in the major political, religious and military developments of the period. During the 1740s, he was an opponent of the First Great Awakening, a Christian revival that swept Great Britain and its North American colonies. Brattle publicly quarrelled with evangelist George Whitefield, a major proponent of the revival who accused Harvard of irreligiosity.

In 1729, Brattle began his military career in the Massachusetts Militia by becoming a member of the Ancient and Honorable Artillery Company of Massachusetts (AHAC). Five years later in 1733, while serving as an officer in the 1st Regiment of Militia of Middlesex, Brattle wrote and published a military manual titled Sundry Rules and Directions for Drawing up a Regiment, which "many an English or American officer packed in his haversack".

In 1745, during a French invasion scare in British North America as a result of King George's War, the governor of Massachusetts William Shirley, of whom Brattle was a strong supporter, appointed him commander of the provincial forces stationed at Castle William; there, Brattle primarily served as a drillmaster. Brattle also served in the colonial militia during the French and Indian War, and by 1760 he had risen to the rank of brigadier-general.

American Revolution and death

In the 1760s, Brattle, by now serving on the Massachusetts Governor's Council, emerged as one of the leaders of colonial opposition to British imperial policies, which were promoted by Governor Francis Bernard and Lieutenant-Governor Thomas Hutchinson. Although sympathetic towards the Sons of Liberty, by 1773 Brattle split with the Patriots over the issue of the salaries of judges; Brattle thought that their salaries should be fixed in order to secure the judges' independence from both the royal governor and the assembly, and published several letters arguing his case.

According to historian William Pencak, from that point on, "Brattle could be counted among the increasing numbers of the old political élite who, while initially having opposed British policy, feared that the growth of popular politics threatened the social order". For shifting his allegiance towards the Loyalist camp, Hutchinson rewarded Brattle with a promotion to the rank of major-general. As head of the colonial militia, Brattle "appeared prominently at the increasingly futile displays of royal authority", and signed a testimonial defending Hutchinson alongside "others of his class".

In 1774, Brattle wrote a letter dated August 27 to Governor Thomas Gage, informing him that stocks of gunpowder belonging to the British colonial government was all that remained in the Old Powder House, a gunpowder magazine on the outskirts of Boston, as the powder owned by the various Massachusetts towns nearby had already been removed. This persuaded Gage to remove the remaining powder for safekeeping by the British, sparking what would become known as the Powder Alarm as news of the attempt spread among angered crowds in the region.

On August 31, Gage dispatched Middlesex County sheriff David Phips to Brattle with orders to remove the powder stores; Brattle handed the magazine key over to Phips. Gage concurrently also lost the letter Brattle wrote to him, which was soon found and publicized by the Patriots. Rumors flared that violence had broken out during the powder's removal; an angry mob surrounded his mansion, forcing Brattle and his family to flee towards Boston seeking British protection. However, the tension eventually subsided as it became apparent that no violence had occurred.

On September 2, several Boston newspapers published a letter from Brattle in which he insisted that he had not warned Gage to remove the powder; according to Brattle, Gage had requested from him an accounting of the storehouse's contents, and he had complied. Brattle remained in Boston, living on British-controlled Castle Island during the outbreak of the Revolutionary War, including the siege of Boston, leaving alongside the British Army when they evacuated the city in March 1776. He died in Halifax, Nova Scotia, on October 25, 1776, at the age of 70.

Personal life, family and legacy

During his life, Brattle gained a reputation as a "jovial, pleasure-loving man" whose political enemies dubbed him "Brigadier Paunch". American statesman John Adams described Brattle as having "acquired great popularity by his zeal, and, I must say, by his indecorous and indiscreet ostentation of it, against the measures of the British government." Brattle was also a slaveholder, being recorded in church records as owning two enslaved women, Philicia and Zillah, in 1731 and 1738 respectively. After his death in Halifax, he was buried in the Old Burying Ground.

In 1727, Brattle married Katherine Saltonstall, daughter of Connecticut governor Gurdon Saltonstall. After she died in 1752, Brattle married Martha Fitch, widow of Boston politician James Allen, in 1755. Brattle had nine children, though only two survived to adulthood, Thomas and Katherine. After the American Revolutionary War, Thomas Brattle managed to convince the government of the United States that he supported had supported the Patriots in the war, despite previously posing as a Loyalist while staying in England, and as such was allowed to keep the family mansion.

A prominent Massachusetts property-owner, he owned properties in Cambridge, Boston, Oakham, Halifax and southeastern Vermont. In Cambridge, Massachusetts, Brattle Street and Brattle Square are both named in his honor, as is the town of Brattleboro, Vermont (which was originally named Brattleborough). The Vermont town was named after Brattle as he was one of Brattleborough's principal proprietors, even though, as noted by Americans historians Austin Jacobs Coolidge and John Brainard Mansfield, there is no record of him ever visiting the settlement.

In the 21st century, the Brattle family's slave-ownership has come under increasing scrutiny and controversy. On April 26, 2022, Harvard University released a report detailing the university's ties to slavery and plans to redress such connections; the report noted that both Brattle and his father, in addition to being prominent Harvard affiliates, were slaveowners. Several writers have made calls to contextualize locations named after Brattle and his father (along with other places with ties to slavery) by noting their slavery connections in order to increase public awareness.