Wallace Stevens facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Wallace Stevens

|

|

|---|---|

Stevens in 1948

|

|

| Born | October 2, 1879 Reading, Pennsylvania, U.S. |

| Died | August 2, 1955 (aged 75) Hartford, Connecticut, U.S. |

| Occupation |

|

| Period | 1914–1955 |

| Literary movement | Modernism |

| Notable works | Harmonium "The Idea of Order at Key West" The Man With the Blue Guitar The Auroras of Autumn "Of Modern Poetry" |

| Notable awards | Robert Frost Medal (1951) |

| Spouse | Elsie Viola Kachel (m. 1909–1955) |

| Children | Holly Stevens (1924–1992) |

| Signature | |

Wallace Stevens (October 2, 1879 – August 2, 1955) was an American modernist poet. He was born in Reading, Pennsylvania, educated at Harvard and then New York Law School, and he spent most of his life working as an executive for an insurance company in Hartford, Connecticut. He won the Pulitzer Prize for Poetry for his Collected Poems in 1955.

Stevens's first period of writing begins with his 1923 publication of the Harmonium collection, followed by a slightly revised and amended second edition in 1930. His second period occurred in the eleven years immediately preceding the publication of his Transport to Summer, when Stevens had written three volumes of poems including Ideas of Order, The Man with the Blue Guitar, Parts of a World, along with Transport to Summer. His third and final period of writing poems occurred with the publication of The Auroras of Autumn in the early 1950s followed by the release of his Collected Poems in 1954 a year before his death.

His best-known poems include "The Auroras of Autumn", "Anecdote of the Jar", "Disillusionment of Ten O'Clock", "The Emperor of Ice-Cream", "The Idea of Order at Key West", "Sunday Morning", "The Snow Man", and "Thirteen Ways of Looking at a Blackbird".

Contents

Life and career

Birth and early life

Stevens was born in Reading, Pennsylvania, in 1879 into a Lutheran family in the line of John Zeller, his maternal great-grandfather, who settled in the Susquehanna Valley in 1709 as a religious refugee.

Education and marriage

The son of a prosperous lawyer, Stevens attended Harvard as a non-degree three-year special student from 1897 to 1900. According to his biographer, Milton Bates, Stevens was personally introduced to the philosopher George Santayana while living in Boston and was strongly influenced by Santayana's book Interpretations of Poetry and Religion (1900). Holly Stevens, his daughter, recalled her father's long dedication to Santayana when she posthumously reprinted her father's collected letters in 1977 for Knopf. In one of his early journals, Stevens gave an account of spending an evening with Santayana in early 1900 and sympathizing with Santayana regarding a poor review which was published at that time concerning Santayana's Interpretations book. After his Harvard years, Stevens moved to New York City and briefly worked as a journalist. He then attended New York Law School, graduating with a law degree in 1903 following the example of his two other brothers with law degrees.

On a trip back to Reading in 1904, Stevens met Elsie Viola Kachel (1886–1963, also known as Elsie Moll), a young woman who had worked as a saleswoman, milliner, and stenographer. After a long courtship, he married her in 1909 over the objections of his parents, who considered her poorly educated and lower-class. As The New York Times reported in an article in 2009, "Nobody from his family attended the wedding, and Stevens never again visited or spoke to his parents during his father's lifetime." A daughter, Holly, was born in 1924. She was baptized Episcopalian and later posthumously edited her father's letters and a collection of his poems.

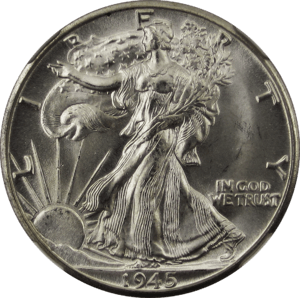

In 1913, the Stevenses rented a New York City apartment from sculptor Adolph A. Weinman, who made a bust of Elsie. Her striking profile may have been used on Weinman's 1916–1945 Mercury dime and the Walking Liberty Half Dollar. In later years, Elsie Stevens began to exhibit symptoms of mental illness and the marriage suffered as a result, but the couple remained married. In his biography of Stevens, Paul Mariani relates that the couple was largely estranged, separated by nearly a full decade in age, though living in the same home by the mid-1930s stating, "...there were signs of domestic fracture to consider. From the beginning Stevens, who had not shared a bedroom with his wife for years now, moved into the master bedroom with its attached study on the second floor."

Career

After working in several New York law firms between 1904 and 1907, he was hired in January 1908 as a lawyer for the American Bonding Company. By 1914 he had become vice-president of the New York office of the Equitable Surety Company of St. Louis, Missouri. When this job was made redundant after a merger in 1916, he joined the home office of Hartford Accident and Indemnity Company and moved to Hartford, where he would remain for the rest of his life.

His career as a businessman-lawyer by day and a poet during his leisure time has received significant attention as summarized in the Thomas Grey book dealing with his insurance executive career. Grey has summarized parts of the responsibilities of Stevens's day-to-day life which involved the evaluation of surety insurance claims by stating: "If Stevens rejected a claim and the company was sued, he would hire a local lawyer to defend the case in the place where it would be tried. Stevens would instruct the outside lawyer through a letter reviewing the facts of the case and setting out the company's substantive legal position; he would then step out of the case, delegating all decisions on procedure and litigation strategy."

In 1917 Stevens and his wife moved to 210 Farmington Avenue where they remained for the next seven years and where he completed his first book of poems, Harmonium. From 1924 to 1932 he resided at 735 Farmington Avenue. In 1932 he purchased a 1920s Colonial at 118 Westerly Terrace where he resided for the remainder of his life. According to his biographer Paul Mariani, Stevens was financially independent as an insurance executive earning by the mid-1930s "$20,000 a year, equivalent to about $350,000 today (2016). And this at a time (during The Great Depression) when many Americans were out of work, searching through trash cans for food."

By 1934, he had been named vice-president of the company. After he won the Pulitzer Prize in 1955, he was offered a faculty position at Harvard but declined since it would have required him to give up his vice-presidency of The Hartford.

Throughout his life, Stevens was politically conservative and was described by the critic William York Tindall as a Republican in the mold of Robert A. Taft.

Travel

Stevens made numerous visits to Key West, Florida, between 1922 and 1940, usually staying at the Casa Marina hotel on the Atlantic Ocean. He first visited in January 1922, while on a business trip. "The place is a paradise," he wrote to Elsie, "midsummer weather, the sky brilliantly clear and intensely blue, the sea blue and green beyond what you have ever seen." The influence of Key West upon Stevens's poetry is evident in many of the poems published in his first two collections, Harmonium and Ideas of Order. In February 1935, Stevens encountered the poet Robert Frost at the Casa Marina.

The following year, Stevens was in an altercation with Ernest Hemingway at a party at the Waddell Avenue home of a mutual acquaintance in Key West. Stevens broke his hand, apparently from hitting Hemingway's jaw, and was repeatedly knocked to the street by Hemingway. Stevens later apologized. Mariani relates this:

... directly in front of Stevens was the very nemesis of his Imagination-- the antipoet poet (Hemingway), the poet of extraordinary reality, as Stevens would later call him, which put him in the same category as that other antipoet, William Carlos Williams, except that Hemingway was fifteen years younger and much faster than Williams, and far less friendly. So it began, with Stevens swinging at the bespectacled Hemingway, who seemed to weave like a shark, and Papa hitting him one-two and Stevens going down 'spectacularly,' as Hemingway would remember it, into a puddle of fresh rainwater.

In 1940, Stevens made his final trip to Key West. Frost was at the Casa Marina again, and again the two men argued. As related by Paul Mariani in his biography of Stevens the exchange in Key West in February 1940 included the following comments:

Stevens: Your poems are too academic.

Frost: Your poems are too executive.

Stevens: The trouble with you Robert, is that you write about subjects.

Frost: The trouble with you, Wallace, is that you write about bric-a-brac.

Post-war poetry

By late February 1947 with Stevens approaching 67 years of age, it became apparent that Stevens had completed the most productive ten years of his life in writing poetry. February 1947 saw the publication of his volume of poems titled Transport to Summer, which was positively received by F. O. Mathiessen writing for The New York Times. In the eleven years immediately preceding its publication, Stevens had written three volumes of poems including Ideas of Order, The Man with the Blue Guitar, Parts of a World, along with Transport to Summer. These were all written before Stevens would take up the writing of his well-received poem titled The Auroras of Autumn.

In 1950–1951 when Stevens received news that Santayana had retired to live at a retirement institution in Rome for his final years, Stevens composed his poem "To an Old Philosopher in Rome" in memory of his mentor while a student at Harvard:

- It is a kind of total grandeur at the end,

- With every visible thing enlarged and yet

- No more than a bed, a chair and moving nuns,

- The immensest theatre, the pillowed porch,

- The book and candle in your ambered room.

Last illness and death

As reported by his biographer Paul Mariani, Stevens maintained a large, corpulent figure throughout most of his life, standing at 6 feet 2 inches and weighing as much as 240 pounds, which required some treating doctors to put him on medical diets during his lifetime. On March 28, 1955 Stevens went to see Dr. James Moher for accumulating detriments to his health. Dr. Moher's examination did not reveal anything and ordered Stevens to undergo an x-ray and barium enema on April 1, neither of which showed anything. On April 19 Stevens underwent a G.I. series that revealed diverticulitis, a gallstone, and a severely bloated stomach. Stevens was admitted to St. Francis Hospital and on April 26 he was operated on by Dr. Benedict Landry.

It was determined that Stevens was suffering from stomach cancer in the lower region by the large intestines and blocking the normal digestion of food. Lower tract oncology of a malignant nature was almost always a mortal diagnosis in the 1950s, although this direct information was withheld from Stevens even though his daughter Holly was fully informed and advised not to tell her father. Stevens was released in a temporarily improved ambulatory condition on May 11 and returned to his home on Westerly Terrace to recuperate. His wife insisted on trying to attend to him as he recovered but she had suffered a stroke in the previous winter and she was not able to assist as she had hoped. Stevens entered the Avery Convalescent Hospital on May 20.

By early June he was still sufficiently stable to attend a ceremony at the University of Hartford to receive an honorary Doctor of Humanities degree. On June 13 he traveled to New Haven to collect an honorary Doctor of Letters degree from Yale University. On June 20 he returned to his home at Westerly Terrace and insisted on working for limited hours. On July 21 Stevens was readmitted to St. Francis Hospital and his condition deteriorated. On August 1, though bedridden, he had revived sufficiently to speak some parting words to his daughter before falling asleep after normal visiting hours were over; he was found deceased the following morning on August 2, 1955 at eight-thirty in the morning. He is buried in Hartford's Cedar Hill Cemetery. Stevens's lifetime parallels almost exactly that of Albert Einstein, who (like Stevens) was born in 1879 and died in 1955.

Paul Mariani in his biography of Stevens, indicates that friends of Stevens were aware that throughout his years and many visits to New York City that Stevens was in the habit of visiting St Patrick's Cathedral for meditative purposes while in New York. Stevens debated questions of theodicy with Fr. Arthur Hanley during his final weeks, and was eventually converted to Catholicism in April 1955 by Fr. Arthur Hanley, chaplain of St. Francis Hospital in Hartford, Connecticut, where Stevens spent his last days suffering from stomach cancer. This purported deathbed conversion is disputed, particularly by Stevens's daughter, Holly, who was not present at the time of the conversion according to Fr. Hanley. The conversion has been confirmed by both Fr. Hanley and a witnessing nun present at the time of the conversion and communion. Stevens's obituary in the local newspaper was minimal at the request of the family as to the details of his death. The obituary for Stevens which appeared in Poetry magazine was assigned to William Carlos Williams who felt it suitable and justified to compare the poetry of his deceased friend to the writings of Dante in his Vita Nuova and to Milton in his Paradise Lost. At the end of his life, Stevens had left uncompleted his larger ambition to rewrite Dante's Divine Comedy for those who "live in the world of Darwin and not the world of Plato."

Awards

During his lifetime, Stevens received numerous awards in recognition of his work, including:

- Bollingen Prize for Poetry (1949)

- National Book Award for Poetry (1951, 1955) for The Auroras of Autumn, The Collected Poems of Wallace Stevens

- Frost Medal (1951)

- Pulitzer Prize for Poetry (1955) for Collected Poems

See also

In Spanish: Wallace Stevens para niños

In Spanish: Wallace Stevens para niños