Vulcan Society facts for kids

The Vulcan Society, founded in 1940, is a fraternal organization of black firefighters in New York City.

Contents

History

Early black recruits to the fire department

Following the 1896 Plessy v. Ferguson ("separate but equal") Supreme Court decision and the 1898 election of Governor Theodore Roosevelt, employment opportunities for black men began to slowly expand. On December 6, 1898, a man named William H. Nicholson was assigned to Brooklyn's Engine Company 6 veterinary department to feed the horses and shovel manure. Engine Company 6 was established in 1869, the year of Nicholson's birth, when it was located at 14 High Street before subsequently relocating, in 1892, to 189 Pearl Street. Engine Company 6, originally a part of the Brooklyn-Queens Fire Department, was inducted into the New York City Fire Department on January 18, 1898, renumbered Engine Company 106 on October 1, 1899, and was again renumbered to its present designation Engine Company 206 on January 1, 1913. Nicholson is known as the first black, New York City fireman of the paid New York City Fire Department, however in 1818 a female slave named Molly Williams had been in the service of Oceanic Engine Company of the old Volunteer Fire Department of New York. According to retired Battalion Chief Wesley Augustus Williams, "Nicholson did not work as a firefighter but was assigned to take care of the horses."

The second black fireman was appointed to the department on September 21, 1914, two years after William Nicholson retired and died. He was John H. Woodson (born 1886), a native of Virginia like Nicholson before him. Woodson's former occupation is listed as mail messenger. John Woodson, like Nicholson, entered the department in his late twenties (Woodson was 28, Nicholson 27). This is a pattern that continues to exist today among minorities appointed to the department. Fireman Woodson, unlike his predecessor, was assigned to Ladder Company 106 in the Greenpoint Section of Brooklyn, to perform regular fire-fighting duties. Woodson had just completed his second year as a fireman when he was awarded a Class III medal for valor (September 22, 1916), and he received a Class "B" citation July 30, 1918. Fireman Woodson transferred to Engine Company 5 in Manhattan from Ladder Company 106, Brooklyn, on May 1, 1918. He spent four months in Engine 5 before transferring to Engine Company 298 in Queens. It was in Engine Company 298 that he spent the majority of his career in the department – August 1, 1918 to March 1, 1934, though he worked in two other companies, Engine 238 and Engine 303 (both in Queens) before retiring on February 1, 1936.

Fireman Woodson had been a member of the department approximately four and a half years when he read an article in The Chicago Defender, a weekly newspaper for black readers, of the impending appointment of another black fireman to the New York City Fire Department, and he wrote to Wesley Williams on January 6, 1919. It was evident that Woodson felt unable to enter that inner circle of companionship enjoyed by his brother white firemen. He wrote that, as a "race" man, he felt it was his duty to inform the newcomer of the conditions which existed in the department at that time. He went on to say that the new fireman would find "quite a lot of jealous and narrow minded men" in the department. On the subject of race relations he warned: "Don't force your friendship on anybody and if there is an argument don't join them; just say I'm neutral." "If they speak of our race before you, in your presence <...> pay no attention – go and do something or take a newspaper and read." However, he concluded his letter, "With best wishes for success and a pleasant career in the Fire Department".

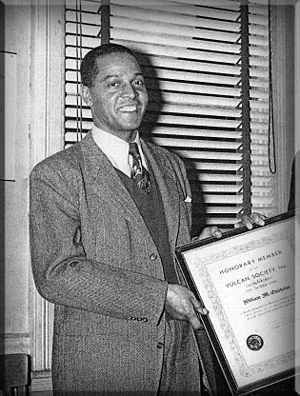

Wesley Augustus Williams

Wesley Williams was a champion amateur weight lifter, and achieved a perfect score of 100% in the physical examination to enter the department. He was the one candidate of the 2,700 competing to score a 100% on the entrance physical examination and only the second man in the history of the department to gain a perfect score. Five years after entering the department in 1924, Williams won the heavyweight boxing championship at a weight of 185 lbs.

Williams was interviewed in 1976, when aged eighty, by Vulcan Society historian John L. Ruffins. Williams was a well-educated grammar school graduate. Following his retirement from the department on April 1, 1952, he remained as active in the business affairs and social life of Harlem. Williams recalled how appreciative he was to receive the letter from Fireman John Woodson a few days before he was appointed in 1919, and commented on how accurately Woodson had stated the facts and the problems he was to face.

Williams had been placed number 13 on the civil service list for appointment as Fireman, New York City Fire Department. Even with his exceptionally high standing on the civil service list it was necessary to present character references. Williams' father was the head Red Cap at Grand Central Station and had developed a personal relationship with the Vanderbilts, the Goulds and the Morgans who were the owners of the railroads and passed through the terminal frequently. Those who signed character references for the young Wesley included former president Theodore Roosevelt. Williams claimed that a previous employer of his father, Mr. Thawley, a millionaire and a heavy contributor to Tammany Hall, was instrumental in letting the "powers that be" (including the fire commissioner and the chief of the department) know that Wesley Williams was in the fire department to stay.

Williams was assigned to Engine Company 55, located at 363 Broome Street, Manhattan, in a predominantly Italian section. When Williams reported for duty on January 10, 1919, the captain retired to avoid the stigma of being the captain of a company where a black fireman was to perform duty. In addition, each man in the company attempted to transfer, stating that they did not wish to work and sleep in the same firehouse with a black man. The department believed if any transfers were permitted, it would have been impossible to keep any fireman in the company, as a result all transfers were denied for at least one year. Fireman Williams was both ignored and ostracized and was given no direct instructions as to his duties or responsibilities. The company was now without a captain and five or six months passed before a replacement was assigned.

When attending his first major emergency, Fireman Williams was ordered to take the nozzle of the hose line down into the cellar. The rest of the company was behind him to assist in moving the hose and to back him up. After the company had moved into place in the smoky cellar a series of explosions occurred and flames rolled over the probationary fireman's head in waves as he operated the nozzle and directed the stream. The company, including the officer, retreated to the street, leaving the probationary fireman in the cellar to extinguish the fire alone. Battalion Chief Ben Parker, on discovering that the probationary man was still in the cellar, chastised the company and the officer for their actions. Fireman Williams established a reputation as a courageous fireman who would not back out in the face of adverse conditions.

Segregation within the fire department

The bed assigned to Wesley Williams was later to be the same bed assigned to any black fireman in any firehouse where he was assigned to perform duty. In Engine 55 it was the bed next to the toilet. No white fireman used the bed, even though the bed linen was changed after each man finished a night tour. This "black bed" became a source of bitter contention for many years in many firehouses.

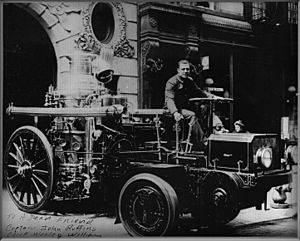

Through his previous experience as a parcel post truck driver, Williams had become proficient in the operation of motor vehicles. It was at this point in the history of the department, horses were being replaced by two-wheel Christie tractors, thus motorizing both steamers and aerial trucks. An 84-hour work week came into being, a system that was to remain practically unchanged until 1939 when the three-platoon eight-hour plan was adopted. The shortage of firemen who possessed the mechanical ability to operate the new gasoline-driven tractors led to Williams being asked to take the apparatus out of quarters and then back it in. He executed the maneuver so expertly he was assigned as the apparatus driver. This assignment caused much resentment against Williams among the members of Engine 55.

It prompted Assistant Chief of Department Patty Walsh to comment that "Of all the men in this Department, he (The Captain) had to pick that man to drive the apparatus!" Tradition dictated that the Motor Pump Operators should be the senior most experienced members of a fire company; the fact that Wesley Williams had little seniority, coupled with the fact that he was black, was not offset by the fact that he was the best qualified to operate the apparatus.

He did however have the run of the quarters, and found the roof to be unoccupied. There in the hose tower, where the wet hoses were hung after a fire he built a gym and kept a bookcase and this was where he spent his off hours exercising and studying fire manuals. The tower was quiet, it extended from above the firehouse roof to the cellar. It was in this small private gym that he continued his routine of physical fitness. An excellent swimmer, when uptown he spent time in the Harlem YMCA where he was schooled in the 'Manly Arts' by some of the sports best, old time prize fighters including Sam Langford, Joe Jeanette and Panama 'Al' Brown. When he was finally called to the cellar of engine co 55, it was not to discuss the merits of gloves vs knuckle. It was to settle a difference of opinion, in the then accepted manner. Whoever left the cellar first was vindicated. Having worked on the sand bag and punching bag until he was proficient led him to have an unfair advantage over the other firemen and having never failed to come out of the cellar first, the message was clear that he could box. In 1924 he entered the FDNY boxing tourney and became the heavyweight champ, only then was it revealed that he was a natural lefty and had a mean left hook that took everyone by surprise.

On Sunday morning, October 19, 1920, a year and ten months after Williams had entered the department, he was walking with his father on St. Nicholas Avenue in Harlem on his way to work. As the two men passed 187 St. Nicholas Avenue they noticed Ladder Company 40 had responded to a fire and had already placed a portable ladder against the front of the fire building. As he and his father approached the building, flames could be seen licking out of the front windows and smoke was partially covering the front of the building. Ladder Company-40's wooden hand-operated aerial ladder was being maneuvered into position against the building so that 19-year-old William Thomas, trapped at a window, could be rescued. After sizing up the situation, Williams ascended the ladder in an effort to assist. As the tip of the aerial ladder approached the panic stricken youth, he made a desperate lunge for it and was successful in grasping the ladder but his grip faltered. As he was beginning to fall, Fireman Williams leaped from the ladder he was standing on, caught the aerial ladder with one hand and the falling Thomas with the other, thus preventing his fall to the street. After carrying the young man to the street and safety, Williams re-ascended the ladder and assisted in the rescue of five other children. The rescue was witnessed by two reporters, and became the subject of an article entitled, "NY's Only Colored Fireman Saves Six From Burning Building".

When Fireman Williams reported to duty and recounted the rescue to his captain, the latter told him that it was in the line of duty and that he would not write it up for submission for a department citation. On another occasion, he and another fireman discovered a fire in a loft building at Spring and Lafayette Streets. Working together, they were able to rescue people from the burning building. Again the captain refused to forward a recommendation; however, the fireman who shared in the rescue reported the particulars to the captain of his company, Ladder 13, who ensured that he received recognition of the performance of an heroic act.

When Williams was promoted to lieutenant in 1927 he was assigned to the same Engine 55 where he had been a fireman, even though it was traditional to assign a newly appointed officer to a firehouse other than where he served as a fireman. The original plan was to assign the first black officer to headquarters and give him a desk job but Lieutenant Williams strongly objected, saying, "I took orders from white officers; white firemen will have to learn to take orders from a colored officer." The day Williams was promoted and assigned as an officer in Engine 55, Fireman John O'Toole walked out of the firehouse, an action that made him immediately AWOL. When Lieutenant Williams admonished an officer for misconduct, charges had to be preferred against the fireman for failure to obey an order. A heavy fine was imposed by the trial commissioner, and the results of the trial were published in the Department Orders; this was official notification that when Lieutenant Williams, like any other officer, issued an order, it was to be obeyed. Seven years after his first promotion, Wesley Williams was promoted to captain in 1934.

Williams had become the company commander of the same firehouse he had entered 15 years ago. During his tour of duty in Engine 55 Wesley Williams had many near escapes in the area known as "Hell's Hundred Acres". Four years after his promotion to captain, Williams was again promoted, this time to Battalion Chief in 1938; he remained in the area because he was assigned to the 3rd Battalion on Mercer Street.

The Vulcan Society

The period from 1936 to 1939 was one of expansion for the fire department. The 1936 sessions of the state legislature adopted bills limiting the hours of duty of all members of the department below 'the Grade of Chief of department to one eight-hour tour in each 24 hours, with one day off each week. The system was launched on March 1 and was completed at the end of 1939. The reduction in hours from 84 a week to 48 necessitated a considerable personnel increase.

The four black firemen who were members of the department in 1936 looked forward to the appointment of 16 additional black firemen who were on the civil service list that was to expire in December 1937. One of these black pioneers was fireman Walter Thomas. He was appointed on December 14, 1937, and served as a member of Ladder Company 41 in west Harlem. Thomas attended evening sessions at the City College of New York (CCNY) from which he graduated cum laude with a Bachelor of Arts degree in 1936, later obtaining his master's degree from CCNY in 1959. Upon his retirement he began a new career as a teacher in the New York public school system.

He later wrote about his experiences, including what he called the "Jim Crow bed", saying:

"In some houses it was proposed to put a screen up to separate this bed from the rest of the dormitory. In other houses the bed was placed next to the toilet. Not only were those considerations humiliating and tending to perpetuate a "place" for the Negro, but this bed situation limited the colored fireman to certain tours, certain vacations, and continually presented him as a candidate for the worst assignment of his tour. In one Company the Negroes weren't allowed to use the same table as the white firemen used. In many companies they weren't invited to use the table but could use it by themselves if they were so bold as to use it. In other companies the colored firemen weren't allowed to contribute money for the commissary—the common stock of sugar, milk, butter, coffee, tea, salt, pepper, mustard, etc.; and other company owned goods.

In many of the houses the most menial porter-type of work was assigned to the Negro fireman. This is the work necessary for the maintenance of quarters. The toilet cleaning, furnace tending, ash removal or whatever work that was considered uninviting was surely to be assigned to the colored fireman. This pattern was followed when assignments to positions on the apparatus were made, and it was an unwritten law that no Negro should drive or be a tillerman high up on the rear of the ladder truck; nor should he operate the pump, neither should he carry certain tools.

One of the toughest jobs on the hook and ladder truck is the assignment to the extinguisher, known as the "can". Filled, it weighs close to thirty-five pounds. Considering the weight of a man's boots, heavy work coat and helmet, the extinguisher becomes a formidable load to run up five flights of stairs, and then into a smoke and heat filled room to try to put out a fire. This was almost inevitably the assignment for the Negro fireman."

However, in many companies there were white firemen and officers who would not participate in this discriminatory conduct. By December of 1937 there were 20 black firemen; by the Fall of 1940 there were fifty-odd black firemen. There was fierce competition for the $3,000 per year job and all but the most qualified Black men were eliminated. Young blacks with the depression era still fresh in their consciousness, who would have become professionals in a healthy economy, turned instead to the fire department and the civil service for employment. At first, when the new group of black firemen experienced psychological tyranny and emotional brutality, Chief Williams visited their respective officers and tried to enlist their aid to correct injustices through moral persuasion. The chief was performing the Herculean task of ambassador; without portfolio. It was abundantly clear that the course of action to follow was the formation of an organization of black firemen.

Chief Williams said, "The men must organize and fight their battles themselves. I was the only officer at that time and did not want the weight of my office to overshadow the will of the body." He therefore decided never to hold office in the newly formed organization. The Vulcan Society of the New York City Fire Department came into being in 1940.

After the society had gained the official blessing of fire headquarters, it was criticized by some sections of the black community who felt forming such an organization was self-segregating. In many ways, the isolation of blacks, one and at the most two, in scattered firehouses made the struggle against existing inequities and injustice extremely difficult. However, the society took the view that firehouses with an all-black complement, including officers, would result in the department being segregated for many years to come, with a resultant loss of opportunity for promotions.

In December 1944, the society conducted a survey throughout the department to determine how widespread were the discriminatory acts and attitudes against black firemen. The verification of a definite pattern of racial discrimination was followed by a hearing before the City Affairs Committee of the New York City Council, initiated by the society. At this public hearing, the society accused the fire department of conscious and deliberate discrimination against black firemen and of permitting the assignment of black firemen to Jim Crow beds in at least twenty firehouses. Subtle changes were subsequently effected, as black firemen began to be assigned as motor pump operators, chauffeurs and tillermen, having become eligible through seniority and experiences. Progress was slow because the policy change was not on an administrative level but was left to the individual company captain.

In 1946, Frank J. Quayle Jr. was appointed Fire Commissioner. Quayle had been a Democratic Party leader in Brooklyn and had gained first hand experience in settling racial and religious group problems among postal employees during his administration as postmaster of Brooklyn. One of Commissioner Quayle's first acts was to meet heads of the department organizations and offer to meet with their committees to discuss their problems. Black firemen continued to make progress under the next administration, that of Fire Commissioner Jacob B. Grumet, formerly a Supreme Court judge and president of the Anti-Defamation Society. The Jim Crow bed became an obsolete practice, and the Vulcan Society continued to grow in numbers as more black firemen were appointed to the department.

From its founding year, 1940, the Vulcan Society played an active role both within the department and in the community. During its early years, it conducted fire prevention programs in the Harlem area placing fire prevention where it was most needed. This program was staffed by off-duty members and was a tangible means of repaying the community for its unwavering support. Recruiting campaigns began in 1946 when the first organized attempt to bring minorities into the department was instituted. Among other early activities was the presentation of a substantial financial contribution to Fire Commissioner Quayle in June 1946 to purchase laboratory equipment for the new Fire Department Medical Clinic.

In the same year, the Vulcan Society participated in a campaign to secure the appointment of a black man to the New York City Board of Education. As the years passed and more black men entered the department, the society increased its community involvement and formed links with the New York City Police Department "Guardians", who were attempting to gain recognition as an official police department fraternal organization. Other civic involvement included submission of proposed amendments to the Multiple Dwelling Law in 1947 directed to the prevention of loss of life in tenement fires. In addition, basketball games were organized between the Vulcan Society and the Guardian Society, the proceeds of which were donated, $1,200 in 1948 and, $10,000 in 1949 to Sydenham Hospital in Harlem. Throughout the 1950s the society made steady progress by adding more members and more officers to its membership rolls. It also was the first organization to become a lifetime member of the NAACP.

Vulcan Fire Commissioner

Robert O. Lowery was appointed a fireman in 1941 and assigned to a firehouse in Harlem; five years later he was designated a fire mashal. The fire marshal's office was the first headquarters assignment black firemen received; in minority areas the investigation of the cause of fires and the apprehension of arsonists was often greatly facilitated by the assignment of minority marshals. Lowery was one of four black firemen in the late 1940s who held this assignment. In the first year as a marshal he received a commendation from Chief Magistrate Edgar Bromberger for the arrest of a man responsible for 30 acts of burglary and arson in Harlem. In 1960 Lowery received a special fire department citation for the capture' of an armed arsonist and in 1961 he was appointed Acting Lieutenant in the Bureau of Fire Investigation in recognition of his outstanding record. During this time Lowery was an active member of the Vulcan Society, serving as its president from 1946 to 1950, 1953 and 1954, 1957, and from 1959 to 1963.

In 1963 a vacancy occurred in the department in the position of Deputy Fire Commissioner. The Vulcan Society petitioned Mayor Robert F. Wagner Jr. to place a black voice in the policy-making echelon of the department. To bring to the mayor's attention the community's support for such an appointment, a petition was circulated that initially contained the signatures of over 20,000 New York City residents. Mayor Wagner appointed Robert. O. Lowery as Deputy Fire Commissioner on November 19, 1963.

In an article in the New York Times of Wednesday, November 25, 1965, then mayor-elect John V. Lindsay is quoted as saying he had been considering Lowery as a potential fire commissioner even before the mayoral election. On January 1, 1966, Robert O. Lowery became the first black fire commissioner of a major city in the United States.

First female president

In 2015 Regina Wilson was elected as the Vulcan Society's first female president in 2015. NYFD Academy instructor Wilson was a 16-year veteran and a member of Engine Co 219 in Park Slope, Brooklyn. She was also the only woman in the class of '99 and one of 10 African-American women in a force of 10,000 in the FDNY. She succeeded Vulcan Society president John Coombs, who cited her election as a historic moment for the organization.

Medals

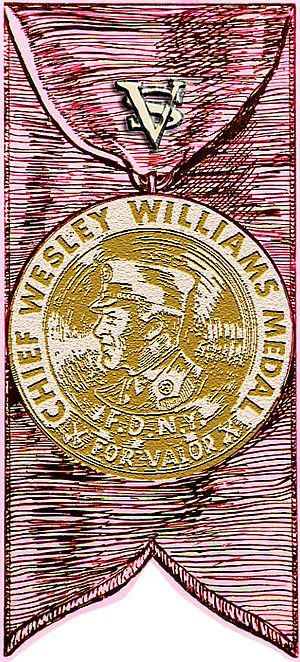

In 1965 the FDNY Medal for Valor named for Batt. Chief Wesley Williams was first awarded during medal day ceremonies. Winners:

- George J Jablonsky, 1965

- Joseph H. Gates, 1966

- Michael Maye, 1967

- William J. Tursellino, 1968

- Edward J. Fusco, 1969

- Richard C. Donovan, 1970

- Chester P. Checkett, 1971

- Richard J. Rittmeyer, 1972

- Harold N. Taylor, 1973

- Charles F.Magrath II, 1974

- Thomas F. Kelly II, 1975

- George W. Hear, Jr., 1976

- Harrison Mckay, 1977

- Albert A. Inglese, 1978

- Thomas J. Potter, 1979

- Ralph L. Oliver, Jr., 1980

- James J. Corcoran, 1981

- James F. Stark, 1982

- Edward P.Moriarty, 1983

- John R. Mcallister, 1984

- Dennis W. Williams, 1985

- Richard P.Kearns, 1986

- Sheldon George 1992

- Carl G. Havens, 1991

- James D. Smith, 2012

- Michael Perrone, 2014

Other awards issued:

- Darrell S. Dennison, 2006, Thomas A. Wylie Medal

- Brian E. Pascascio, 2007, Arthur J Laufer Memorial Medal

Further sources

- Smith, Terrence (Nov 24th, 1965) Lindsay selects negro as first fire commissioner, New York Times

- United States of America and Vulcan Society, Inc. v. City of New York

- Goldberg, David (2020). Black Firefighters and the FDNY: the struggle for jobs, justice, and equity in New York City. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press. ISBN: 978-1-4696-6146-9