United States v. Kagama facts for kids

Quick facts for kids United States v. Kagama |

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Submitted May 10, 1886 Argued March 2, 1886 |

|

| Full case name | United States v. Kagama, alias Pactah Billy, an Indian, and another. |

| Citations | 118 U.S. 375 (more)

6 S. Ct. 1109; 30 L. Ed. 228; 1886 U.S. LEXIS 1939

|

| Holding | |

| The Major Crimes Act was constitutional, and, therefore, the case was within the jurisdiction of the federal courts. This ruling meant that the San Francisco Court's indictment would stand. | |

| Court membership | |

| Case opinions | |

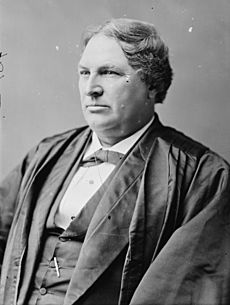

| Majority | Miller, joined by unanimous |

| Laws applied | |

| U.S. Const. Art. I, § 8, cl. 3; 18 U.S.C. § 1153 | |

United States v. Kagama, 118 U.S. 375 (1886), was a United States Supreme Court case that upheld the constitutionality of the Major Crimes Act of 1885. This Congressional act gave the federal courts jurisdiction in certain Indian-on-Indian crimes, even if they were committed on an Indian reservation. Kagama, a Yurok Native American (Indian) accused of murder, was selected as a test case by the Department of Justice to test the constitutionality of the Act.

The importance of the ruling in this case was that it tested the constitutionality of the Act and confirmed Congress's authority over Indian affairs. Plenary power over Indian tribes, supposedly granted to the U.S. Congress by the Commerce Clause of the Constitution, was not deemed necessary to support the Supreme Court in this decision. Instead, the Court found the power in the tribes' status as dependent domestic nations, which allowed Congress to pass the Dawes Act the following year. The case has been criticized by legal scholars as drawing on powers that are not granted to Congress by the Constitution, but it remains good law.

Contents

Background

Hoopa Valley Reservation

The Hoopa Valley Reservation was created by executive order in 1864. At the time the reservation was formed, three unique bands of Indian tribes lived on different parts of the Klamath River, each with its own language. The Yurok lived on the Lower Klamath, the Karuk occupied the Upper Klamath and the Hupa lived at the confluence of the Trinity and Klamath Rivers in Humboldt County, California. The reservation was supposed to be a home for other tribes within the region.

The tribes living along the river had long-established rules for property rights and ownership, including how property was to be passed down from one generation to the next. In some cases, families owned lands that were located a substantial distance from their "home" village.

In charge of the reservation was the Indian agent, Major Charles Porter, who by commanding the local military garrison (Fort Gaston) on the reservation was charged with the de facto responsibility for the people on the reservation. Without legal authority and against government policy, Porter allotted small parcels of land to the local Indian people, thus upsetting an age-old property rights system among families in the Klamath River Valley. On several occasions, Agent Porter had been called out to Kagama and Iyouse's homes to mediate their property dispute. Shortly before the murder, Kagama requested title to the land upon which he built his home.

Supreme Court

Arguments

Kagama was represented by 27-year-old Joseph D. Redding. The United States was represented by George A. Jenks, who was an Assistant United States Secretary of the Interior. Arguments were heard before the Supreme Court on May 2, 1886, only five months after the circuit court delivered a split opinion on the matter of jurisdiction.

Jenks urged the court to look to its earlier ruling in Crow Dog, where the Court commented in dicta that Congress possessed the authority to regulate all commerce with Indian tribes, because of the Indian Commerce Clause of the Constitution. In his listing of precedents, he cited numerous laws passed by Congress regulating Indian commerce; he did not cite any other case law that supported Congress' authority over internal Indian matters, because there was none. Further, Jenks incorporated aspects of the political debate in Congress when the act was passed citing that the U.S. should be able to enforce its laws within its borders, regardless of treaty rights. The prosecution argued that Congress had the absolute authority to regulate Indians and their affairs.

Joseph Redding defended his clients vigorously. His argument was three-fold. First he argued that in one hundred years of Indian policy, Congress had never prosecuted Indian-on-Indian crime. Further, the indictment as stated contained no element of commerce and was therefore outside the purview of Congress to legislate such a law. Finally, he argued that such a profound shift in Indian policy should not be enacted in a law whose heading and body were wholly inconsistent with the intent of the Major Crimes Act. In effect, he argued that such a law governing a people should be debated in full sight of the American public and on its own merits. Redding argued that Congress could not assert power over sovereign people who, when making treaties to cede land, reserved certain rights to themselves. He did not raise the issue that the tribes already did have a system of law that dealt with crimes against another person.

Opinion of the Court

In a unanimous decision issued at the end of May 1886, and authored by Justice Samuel Freeman Miller, the Supreme Court ruled that the Major Crimes Act was constitutional, and, therefore, the case was within the jurisdiction of the federal courts. Miller dismissed the argument that the Act was proper under the Indian Commerce Clause, noting that the case did not present a commerce issue. He held instead that it was necessary since Indians were wards of the United States. Justice Miller was known for writing opinions that supported federal power over state's rights. This ruling meant that the federal circuit court's indictment would stand and the case would proceed to trial back in Northern California.

The opinion drew heavily on the language of the Solicitor General's brief, which by today's standards would be considered by many as racially charged. The language in Miller's opinion is infamous for its description of Indian tribes as weak, degraded and dependent on the federal government for support. He adopts language from Cherokee Nation v. Georgia describing each tribe as a "ward" and in a state of "pupilage."

Miller, having dismissed the Indian Commerce Clause as a source of authority, did not cite another constitutional source of the power. In effect, this decision contended that the U.S. government had supreme authority to enforce laws within its borders, but did not mention where this power was outlined in the Constitution. From the time the crime occurred to the Supreme Court decision, eleven months had passed.

Subsequent developments

Trial of Kagama

The trial was held in San Francisco in September 1886. The prosecution called four witnesses, including Iyouse's wife and a witness to the murder named "Charlie". The defense called one witness, John B. Treadwell. Treadwell testified that the murder was outside the boundaries of the reservation. Based on Treadwell's position within the General Land Office, the judge believed him and ordered a directed verdict of not guilty.

Humboldt County Sheriff T. M. Brown stated that he would not arrest Kagama for a crime against another Indian. Brown stated that in his 26 years of law enforcement in the area, the state had never prosecuted an Indian for Indian-on-Indian crime. Brown also said that Kagama was trustworthy and industrious, while the victim was a "treacherous" blackmailer who had already killed several men. The sheriff believed that Kagama did not have any option but to kill the victim.

Consequences and criticism of the decision

Kagama was the case that articulated Congress' plenary power over the Native American tribes in the late 19th century. It reaffirmed Congress' power to pass legislation, including the Dawes Act, that would take away many of the liberties that Native Americans had been able to hold on to up until that point. 19th and early 20th century U.S. lawmakers viewed the American Indians as inferior people who would benefit from being assimilated into the Euro-American culture. The laws that followed the Kagama ruling were attempts to destroy the Native American cultural differences and force these tribes to share the Euro-American culture viewed by these lawmakers to be the superior culture.

The decision has been widely criticized by legal scholars. David E. Wilkins noted that if the Indian Commerce Clause or Taxation Clause did not contain the authority, and the tribes had not granted it by treaty or consent, then the Major Crimes Act would be unconstitutional and the Court should have declared it void. Phillip P. Frickey describes the Kagama decision as "a whirlwind of circular reasoning", with the Court justifying congressional power due to the tribe's weakness, which it also noted was due to the tribes dealing with the U.S. government. Frickey felt the decision was an embarrassment to constitutional theory, to logic, and to humanity. Robert N. Clinton stated that "[t]his remarkable decision obviously invoked rhetoric of colonial expansion, rather than the rhetoric of American constitutional discourse." Daniel L. Rotenberg said that Kagama was "one more item on the long litany of injustices to the American Indian." In addition to the law professors, various other authors in law reviews have also been critical of the decision. Warren Stapleton, in the Arizona State University law journal, has stated that the decision was incorrect and that the Major Crimes Act is in fact unconstitutional. In a Comment, the University of Pennsylvania Law Review noted that "the Court promulgated what can be called the 'it-must-be-somewhere' doctrine ..."

Kagama remains good law, being cited in support of the plenary power doctrine as recently as 2004 in United States v. Lara by the Supreme Court, and cited in 2015 by the 6th Circuit. Although one legal scholar, Matthew L.M. Fletcher, states that the apex of the doctrine was reached in 1955, in Tee-Hit-Ton Indians v. United States, he also acknowledges that the doctrine is still current law. In 2010, Pawnee lawyer Walter Echo-Hawk wrote in his book, In the Courts of the Conqueror, that Kagama has been used:

[T]o justify excessive government intrusion into the internal affairs of Indian tribes and to exercise unwarranted control over the lives and property of American Indians in a slide towards despotism ... [T]he creation of frightening, state-run, Orwellian societies on Indian reservations was perfectly legal in the courts of the conqueror, because it was done in the name of guardianship.