Tiberius Gracchus facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Tiberius Sempronius Gracchus

|

|

|---|---|

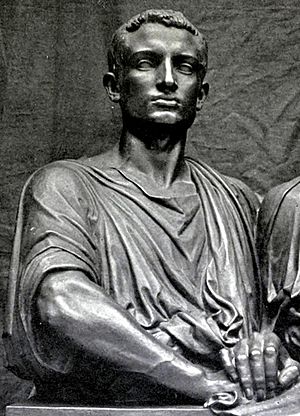

A bust of Tiberius from a 19th century commemorative sculpture of the Gracchi brothers by Eugène Guillaume

|

|

| Born | c. 163 BC |

| Died | 133 BC (aged probably 29) |

| Cause of death | Blunt trauma |

| Known for | Agrarian reforms |

| Office | Tribune of the plebs (133 BC) |

| Children | 3 sons (died young) |

| Parent(s) | Tiberius Sempronius Gracchus and Cornelia |

| Relatives | Gaius Gracchus (brother) Sempronia (sister) Scipio Nasica Serapio (cousin) Scipio Africanus (grandfather) |

| Military career | |

| Rank | Military tribune and quaestor |

| Wars |

|

Tiberius Sempronius Gracchus (c. 163 – 133 BC) was a Roman politician best known for his agrarian reform law entailing the transfer of land from the Roman state and wealthy landowners to poorer citizens. He had also served in the Roman army, fighting in the Third Punic War and in Spain.

Against substantial opposition in the senate, his land reform bill was carried through during his term as tribune of the plebs in 133 BC. Fears of Tiberius' popularity and willingness to break political norms, incited by his standing for a second and consecutive term as tribune, led to him being killed, along with many supporters, in a riot instigated by his enemies. A decade later, his younger brother Gaius proposed similar and more radical reformist legislation and suffered a similar fate.

The date of his death marks the traditional start of the Roman republic's decline and eventual collapse.

Contents

Background

Tiberius Sempronius Gracchus was born in 163 or 162 BC, being "not yet thirty" at his death. He was, from birth, a member of the Roman Republic's aristocracy.

His homonymous father was part of one of Rome's leading families. He served in the consulships for 177 and 163 BC, and was elected censor in 169. He also had celebrated two triumphs during the 170s, one for the victorious establishment of a twenty-year-long peace in Spain. His mother, Cornelia, was the daughter of the renowned general Scipio Africanus, the hero of the Second Punic War. His sister Sempronia was the wife of Scipio Aemilianus, another important general and politician. Tiberius was raised by his mother, with his sister and his brother Gaius Gracchus.

Tiberius Gracchus married Claudia, daughter of the Appius Claudius Pulcher who was consul in 143 BC. Appius was a major opponent of the Scipios, a family with which Tiberius was related in his maternal line. The date of the marriage is uncertain; it could have been related to a plan to reconcile the two families. His marriage to Pulcher's daughter, however, did cement the friendship between Tiberius Gracchus' father and Appius into his generation.

Military career

Tiberius' military career started in 147 BC, serving as a legate or military tribune under his brother-in-law, Scipio Aemilianus during his campaign to take Carthage during the Third Punic War. Tiberius, along with Gaius Fannius, was among the first to scale Carthage's walls, serving through to the next year.

In 137 BC he was quaestor to consul Gaius Hostilius Mancinus and served his term in Hispania Citerior (nearer Spain). His appointment to Hispania Citerior, supposedly by lot, was very obviously manipulated. The campaign was part of the Numantine War and was unsuccessful; Mancinus and his army lost several skirmishes outside the city before a confused night-time retreat that led them to the site of a camp from a former consular campaign in 153 BC where they were surrounded. He was forced to send his quaestor to negotiate a treaty of surrender. Gracchus' negotiations were successful, in part to his inheriting Spanish connections from his father's honourable and good dealings in the area during his praetorship in 179–78 BC. During the negotiations, Tiberius requested the return of his quaestorian account books which were taken when the Numantines had captured the Roman camp; the Numantines acquiesced.

The Numantines also had previously signed a treaty with Rome a few years earlier under Quintus Pompeius but Rome had reneged on those terms, the treaty's ratification being rejected due to the terms being too favourable. Tiberius' new treaty also was rejected: the Romans rejected the terms as humiliating and would strip Mancinus of his citizenship and send him stripped and bound to the Numantines. However, by the time the terms of this agreement were being debated in the senate, Numantine ambassadors had also arrived and Mancinus likely argued in favour of his own ritual surrender, felt confident in his safety, and wanted to look towards making a soft landing for his career.

Tiberius, who Cassius Dio says expected to be rewarded for his conduct of the negotiations, quickly changed his position, distancing himself from his own treaty, especially as the Roman state's rejection of the treaty dealt a "blow to his reputation for good faith (fides)". Around this time, Tiberius also was likely co-opted into the college of augurs.

Mancinus argued that his men were undertrained due to his predecessor's defeats; at the same time, Tiberius was claiming the cause of the defeats were related to diminishment of the yeomanry. Mancinus would have his citizenship later restored by special act of the people, re-entered the senate, and was eventually elected to a second praetorship; he never however commanded troops in the field again.

Tribunate

Tiberius Gracchus was elected as plebeian tribune for 133 BC. While Livy's depiction of the middle republic as being "largely devoid of domestic strife" is an overstatement, the political culture in Rome at this time still was able to find solutions through negotiation, peer pressure, and deference to superiors.

There was a substantial demand among the poor for land redistribution; Gracchus enjoyed "unparalleled popular support" in bringing the matter before the Assemblies. Tiberius' unwillingness to stand aside or compromise broke with political norms. A similar land reform proposal by Gaius Laelius Sapiens during his consulship in 140 BC was withdrawn after bitter opposition and its defeat in the senate.

The motives of Tiberius and his ally and father-in-law Appius Claudius Pulcher were "doubtless complex" and may also have been motivated not only by a desire to support the state's ability to recruit soldiers or general pro-natalist policymaking, but also by "the reflection that [land reform's] grateful beneficiaries would include the veterans whom Scipio [Aemilianus] would shortly be bringing back [from] Numantia". The proposal would also serve a prominent "counter-stroke on the domestic front" after Aemilianus' expected foreign victory.

Roman land crisis

At the time of Gracchus' tribunate in the late 130s BC, there were a number of economic issues before the Roman people: wage labour was scarce due to a dearth of public building, grain prices were likely high due to the ongoing slave rebellion in Sicily, population growth meant there were more mouths to feed, and declining willingness to serve on long army campaigns had increased migration to the cities.

Altogether, these trends reduced the opportunities for people in the cities to support themselves, driving them closer to subsistence. Influx into the cities was not high by modern standards: large numbers of people remained in the countryside. But similar issues plagued the rural poor as well. The absence of colonisation projects and increased demand for wage labour on large farms "may have caused an oversupply of labour in the country, [making] it difficult for the rural poor to support themselves".

The Roman state owned a large amount of public land, or ager publicus, acquired from conquest. The state, however, did not exploit this land heavily. While it was theoretically Roman property, the land "had been regarded as a sort of beneficium to the allies, who had been allowed to continue to work the land which had been confiscated from them".

The traditional story, that the ager publicus was dominated by a "rich commercial elite [that] established large slave-staffed estates on public land" driving poor farmers into destitution between military service and competition with slave labour, is increasingly questioned due to the location of the ager publicus itself. The ager publicus was mainly located outside of the traditional farmland close to Rome. It was located mainly in places inhabited by non-Roman citizens.

The expanded population of Italy in the second century BC had split up, due to Roman practice of partible inheritance, previously modest agricultural properties into plots too small to feed a family. This caused higher underemployment of farmers, who were willing to sell their lands to richer men because the high demand for land near Rome had driven up the prices dramatically; farmers who sold their land engaged in wage labour, which was a major source of employment: "there is ample evidence to show that the temporary labour of free men was very important to large estates" especially around harvest-time.

People also could move to the cities to find jobs in public works, day jobs such as moving things, and selling food; after 140 BC, however, public monumental projects etc had paused. Alternate occupations included the army, but by the late 130s BC, army life remained poor and the massive riches of the early 2nd century had given way to the conquest of Hispania, where "the chance of profit was small and the chance of dying great". There are many contemporaneous reports of endemic desertion, draft evasion, and poor morale.

The claims which the Gracchans made about the depopulation of the countryside "have long since been shown to be false". Ancient sources note an inability to find men to serve in the Spanish wars, but "at the time apparently nobody connected [unwillingness to serve in Spain] with under-registration in the census". It therefore would have appeared to Gracchus and other Roman leaders that there was a population decline and manpower shortage, even if the population had actually increased (something which the Romans eventually figured out in the census of 125/4 BC).

Lex agraria

Previous legislation had limited the amount of land that any person could hold to 500 jugera (approximately 120 hectares), this law was largely ignored and many people possessed far more than the limit, including Marcus Octavius, also serving as tribune in that year, and P Cornelius Scipio Nascia, then pontifex maximus.

The way that Gracchus sold his agrarian reforms is heavily reported in Appian and Plutarch. Modern scholars, however, had argued that their accounts do not reflect land in the second century objectively, but they do well-reflect the arguments which Gracchus and others gave for doing land reform. Gracchus and his supporters summarised the problem in terms of the poor being driven off land by the slave-owning rich, a decline in wage labour, people refraining from having children they cannot feed, and a consequent decline in living standards and the number of available soldiers.

To resolve his identified issue, Tiberius Gracchus' law would enforce a limit on the amount of public land that one person could hold; the surplus land would then be privatised into the hands of poor Roman citizens. Benefitting the poor was not the only goal of his legislation: Gracchus also intended to reduce the level of inflammation in the city by moving the poor into the countryside while also endowing those people with the necessary land to meet army property qualifications. But less incidentally, the privatisation project itself would serve to increase the number of potential recruits for the army while also eventually stimulating population growth to reverse the apparent decades-long manpower shortage.

It is natural that his agrarian policy, focusing on people with the skills to do agriculture, led to much of his support coming from the poor rural plebs (eg "the rural poor, very small owners, the younger sons of yeomen whose farms brooked no division...") rather than the plebs in the city. Thousands apparently flooded in from the countryside to support Gracchus and his programme. He was not, however, some maverick in his views and was certainly not alone: he was supported by one of the consuls for the year (the jurist Publius Mucius Scaevola), his father-in-law Appius Claudius Pulcher (who had served in the consulship for 143 BC), "the chief pontifex P Licinius Crassus Mucianus", and other younger junior senators.

It is not known how much the recipients of redistribution would have got. Thirty jugera is often suggested, but this is rather large compared to the amount of land distributed to each family during Roman colonisation projects (only 10 jugera). Tiberius Gracchus' law also prohibited recipients from selling the land they received and possibly also required them to pay some rent (a vectigal) to the public treasury. While these conditions place the private ownership of the distributed land into question, and therefore also question whether an owner could be registered in the census as owning that land, it is likely that the land was fully privatised but given conditional on payment of the vectigal. If the vectigal were unpaid, the land would revert to the state, which would then be able to redistribute it to a new settler.

The law would also create a commission, staffed by Tiberius Gracchus, his brother Gaius Gracchus, and his father-in-law, Appius Claudius Pulcher, to survey land and mark which illegally-occupied land was to be confiscated.

Passage of the lex agraria

Obviously, the people possessing more than 500 jugera of land opposed the law strongly. While previous practice had given fines for doing so, those fines were rarely enforced and the land possession itself was not disturbed. This led them to invest into improvements to that land, with some protests that the land was part of wives' dowries or the site of family tombs. Tiberius Gracchus' law would seize the land explicitly, a novel innovation. According to Plutarch, Tiberius initially proposed compensation, but proposal was withdrawn; his later proposal was to compensate by securing tenure with a cap of 500 jugera.

The exact legislative history of the bill is disputed: Appian and Plutarch's accounts of the bill's passage differ considerably. At a broad level, the bill was proposed before the concilium plebis; Tiberius forwent the approval of the senate before a bill was to be introduced. In response, the senate sought a fellow tribune to veto the proceedings. Both versions agree on the deposition of Octavius.

In Plutarch's account, Tiberius proposes a bill with various concessions, which is then vetoed by Marcus Octavius, one of the other tribunes. In response, he withdraws the bill and removes the concessions. This latter bill is the one debated heavily in the forum. Tiberius tries various tactics to induce Octavius to abandon his opposition: offering him a bribe and shutting down the Roman treasury, and thereby, most government business. When the Assembly eventually assembles to vote, a veto is presumed. They attempt to adjudicate the matter in the senate, to no avail, and the Assembly votes to depose Octavius from office when he maintains his veto. Following the deposition, Gracchus' freedmen drag Octavius from the Assembly and the Assembly passes the bill.

In Appian's account, however, there is only one bill: opposition from Octavius appears only at the final vote, leading to the dispute to be taken to the senate, and then Octavius' deposition followed by the bill's passage. Prior to the vote, Tiberius gives a number of speeches, in which Appian asserts that Tiberius passed the bill on behalf of all Italians.

The dispute between Tiberius Gracchus and Octavius was a political dispute which lacked a clear resolution, as the Roman constitution was unwritten and only worked properly when all actors worked cooperatively instead of "making use of their full legal powers". Both men, being tribunes, represented the people writ large. Octavius insisted on maintaining his veto in defiance of the clearly expressed views of his constituents; Gracchus' response was to "[depose] and [manhandle] an elected tribune of the plebs" in a "similarly unprecedented breach of political behaviour". As a whole, while Tiberius had "probably departed from constitutional practice in proposing [the bill] without consulting the senate... Octavius was guilty of a graver impropriety in seeking to hinder the tribes from voting on the proposal".

Opposition and death

After passage of the bill, the senate allocated a nugatory grant of money for the commissioners, which made it impossible for the commission to do its job when it needed to pay for surveyors, pack animals, and other expenses. Fatal resistance to Gracchus' law, however, did not emerge until Tiberius proposed using the bequest of Attalus III of Pergamum to finance the land distribution and commission. It is not clear for what purpose this money was to be used: Plutarch asserts it was to be used to buy tools for the farmers, Livy's epitome asserts it was to be used to purchase more land for redistribution in response to an apparent shortage. The latter is unlikely, as merely determining how much ager publicus was available for redistribution had not started and would be extremely time-consuming; it is also possible the money was to be used to finance the commission itself. After this proposal, Tiberius was attacked in the senate by Quintus Pompeius, accused of harbouring decadent regal ambitions.

The explicit purpose of the money aside, Gracchus was breaking a major norm in Roman politics, which placed the finances and foreign policy exclusively in the hands of the senate. Senators also feared that Gracchus intended to appropriate Attalus' bequest to hand out money, which would massively benefit him personally. This was compounded by his attempt to stand for re-election, claiming that he needed to do so to prevent repeal of the agrarian law or possibly to escape prosecution for his deposition of Octavius. His bid for re-election was possibly in violation of Roman law. The bid, however, certainly violated Roman constitutional norms and precedents; some ancient historians also report that Tiberius, to smooth his bid for re-election, brought laws to create mixed juries of senators and equites but this "doubtless reflect[s] confusion with [his brother's] later measures". The deadly opposition to Tiberius Gracchus' reforms were focused, however, more on his subsequent actions than on the reforms themselves.

Tiberius' re-election bid "presented the Scipionic group with an issue to use against their political enemies": at the electoral comitia counting the votes for the tribunes for 134 BC, Tiberius and his entourage were attacked by a mob led by his first cousin Publius Cornelius Scipio Nasica, the pontifex maximus. Scipio Nasica first attempted to get consul Publius Mucius Scaevola to kill Gracchus during a senate meeting on Gracchus' imminent re-election; when the consul refused, saying he would not use force or kill a citizen without trial, Scipio Nasica shouted a formula for levying soldiers in an emergency – "anyone who wants the community secure, follow me" – and led a mob to the comitia with his toga drawn over his head. In doing so, he attempted to enact an "ancient religious ritual killing (consecratio) ... presumably on the grounds that [Gracchus] was trying to seize power and overthrow the existing republic". Tiberius and supporters fell without resistance; their bodies were thrown into the Tiber. This opposition was political: Gracchus' land reforms "may have been acceptable", but not when combined with his seeming threats "to make the urban populace and the small peasants his personal clientelae".

After his death

Tiberius' agrarian law was not repealed, likely because doing so would have been too unpopular to be "safe or practicable". His position on the agrarian commission was filled; the commission's business continued over the next few years: its progress can be observed in recovered boundary stones stating the commissioners' names. Most of those boundary stones bear the names of Gaius Gracchus, Appius Claudius Pulcher, and Publius Licinius Crassus. An increase in the register of citizens in the next decade suggests a large number of land allotments. But that registration could also be related to greater willingness to register: registration brought the chance of getting land from the commission. It also could have been related to lowering of the property qualifications for census registration into the fifth class from four thousand to 1.5 thousand asses.

That said, the activities of the land commission started to slow after 129 BC. The senate pounced on complaints from Italian allies that the land commissioners were unfairly seizing land from Italians. Scipio Aemilianus, arguing on behalf of the Italians, convinced the state to move decisions on Italian land away from the land commissioners on grounds of prejudice, to the consuls; the consuls promptly did nothing, stalling the commission's ability to acquire new land to distribute. However, over the few years of the commission's most fruitful activities, the amount of land distributed was "quite impressive": the Gracchan boundary stones are found all over southern Italy, and distributed some 1.3 million jugera (or 3 268 square kilometres), accommodating somewhere between 70 and 130 thousand settlers. Shortly after this intervention, Scipio died mysteriously, leading to unsubstantiated rumours that his wife (also Tiberius Gracchus' sister), Gaius Gracchus, or other combinations of Gracchan allies had murdered him.

Some Gracchan supporters were prosecuted in special courts established by the senate under the supervision of the consuls for 132 BC.

Legacy

Tiberius' brother, Gaius Sempronius Gracchus, continued his career without incident until he too stood for the tribunate and proposed similarly radical legislation, before also being killed with now explicit approval of the senate. Part of Gaius' land programmes was to start establishing Roman colonies outside of Italy, which later became standard policy: "[he] apparently was the first to realise that the amount of land in Italy was insufficient to provide for all inhabitants of the peninsula".

Personally, the killing of Tiberius also caused a greater break between Scipio Aemilianus and his Claudian and Gracchan relatives.

Political impact

The impact of Tiberius' murder started a cycle of increased aristocratic violence to suppress popular movements. Roman republican law, when passing ostensibly capital sentences, explicitly permitted convicts to flee the city into permanent exile.

The senate's continued pursuit of Tiberius Gracchus' supporters also entrenched polarisation in the Roman body politic.

Periodisation

In terms of periodisation, the death of Tiberius Gracchus in 133 BC is and was viewed, both in the late republic and today, as the start of a new period in which politics was polarised and political violence normalised.

In the ancient period, Cicero remarked as much in saying "the death of Tiberius Gracchus, and even before that the whole rationale behind his tribunate, divided a united people into two distinct groups" (though Beard also warns against this as a "rhetorical oversimplification": "the idea there had been a calm consensus at Rome between rich and poor until [133 BC] is at best a nostalgic fiction").

More modern commentators also express similar views.

Impact on the Italian allies

Against Appian's claims about how Tiberius acted to give Rome's Italian allies land, there are no seeming indications that Tiberius Gracchus' reforms helped them in any way: the assignments "most likely benefited only Roman citizens, while Italians did not receive land". Moreover, it was the Italian allies who launched the fiercest opposition to the land reform programme; Tiberius Gracchus' supporters also are never Italians in Appian's account, but only rural plebeians.

After Rome acquired its public lands via conquest, "many Italians had simply continued to use [officially confiscated land]; by now, this situation had lasted seventy years, and the Italians expected to be able to keep [it] as long as they did not rebel against Roman overlordship". While those who complained the most were likely rich over-occupiers, Appian also reports that the commission's work was "often done in haste and inaccurately". Furthermore, the land given in exchange for land taken per the lex agraria might have been of inferior quality, also stoking resentment.

The loyalty of the Italian allies during the Punic wars and other conflicts therefore "had earned them nothing, or at least it had not ensured them the complete enjoyment of the land they had always considered their own". In the end, Roman enforcement of its long-unexercised rights over the ager publicus "was one of the causes of the Social War between Rome and many of its Italian allies, since it deprived the Romans of an important instrument [to] ensure their allies' loyalty".

The interaction between the Italians and land reform also brought up later proposals, including those from Marcus Fulvius Flaccus and also Gaius Gracchus, to placate the Italian aristocracy that would lose portions of their land with the granting of Roman citizenship or rights of provocatio.

Modern legacy

The French revolutionary François-Noël Babeuf took up the name Gracchus Babeuf in emulation of the then-contemporary view of the Roman brothers as revolutionaries who were misinterpreted as seeking limitations on private property. He also published a newspaper, Le tribun du peuple ("the tribune of the people"). Modern perspectives see the comparison unapt: "In stark contrast to the Gracchi, he was concerned with the private ownership of land, not public, and his most extreme programme sought in fact to do away with the former completely ... The Gracchi sought to strengthen and uphold the Roman republic; Babeuf wished to overthrow and radicalise the French republic".

See also

In Spanish: Tiberio Sempronio Graco para niños

In Spanish: Tiberio Sempronio Graco para niños

- Gaius Gracchus, his brother

- Gracchi brothers

- Scipio–Paullus–Gracchus family tree