The Tale of Mrs. Tittlemouse facts for kids

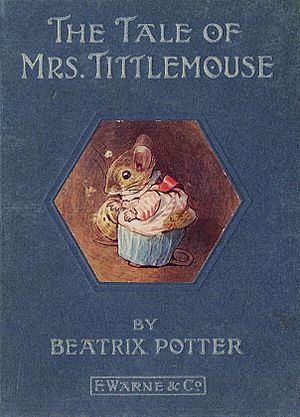

First edition cover

|

|

| Author | Beatrix Potter |

|---|---|

| Illustrator | Beatrix Potter |

| Country | England |

| Language | English |

| Genre | Children's literature |

| Publisher | Frederick Warne & Co. |

|

Publication date

|

July 1910 |

| Media type | Print (hardcover) |

| Preceded by | The Tale of Ginger and Pickles |

| Followed by | The Tale of Timmy Tiptoes |

The Tale of Mrs. Tittlemouse is a children's book written and illustrated by Beatrix Potter, and published by Frederick Warne & Co. in 1910. The tale is about housekeeping and insect pests in the home, and reflects Potter's own sense of tidiness and her abhorrence of insect infestations. The character of Mrs. Thomasina Tittlemouse debuted in 1909 in a small but crucial role in The Tale of The Flopsy Bunnies, and Potter decided to give her a tale of her own the following year. Her meticulous illustrations of the insects may have been drawn for their own sake, or to provoke horror and disgust in her juvenile readers. 25,000 copies of the tale were initially released in July 1910 and another 15,000 between November 1910 and November 1911 in Potter's typical small book format.

Mrs. Tittlemouse is a woodmouse who lives in a "funny house" of long passages and storerooms beneath a hedge. Her efforts to keep her dwelling tidy are thwarted by insect and arachnid intruders who create all sorts of messes about the place: a lost beetle leaves dirty footprints in a passage and a spider inquiring after Miss Muffet leaves bits of cobweb here and there. Her toad neighbour Mr. Jackson lets himself into her parlour, stays for dinner, and searches her storerooms for honey but leaves a mess behind. Poor Mrs. Tittlemouse wonders if her home will ever be tidy again, but after a good night's sleep, she gives her house a fortnight's spring cleaning, polishes her little tin spoons, and holds a party for her friends.

Potter's life had become complicated with the demands of ageing parents and the business of operating a farm before the composition of Mrs. Tittlemouse, and, as a consequence, her literary and artistic productivity began a decline following the tale's publication. She continued to publish sporadically but much of her work was drawn from decades-old concepts and illustrations. Mrs. Tittlemouse marks the end of her two books a year output for Warnes. Scholars find the book's depictions of the insects its great attraction. One critic finds a "nightmarish quality" in the tale reflected in Mrs. Tittlemouse's almost endless war waged against insect pests. Characters from the tale have been modelled as porcelain figurines by Beswick Pottery beginning in 1948, and the mouse's image appeared on a Huntley & Palmer biscuit tin in 1955. Other merchandise has been marketed depicting Mrs. Tittlemouse and her friends. Mrs. Tittlemouse was a character in a 1971 ballet film and her tale was adapted to an animated television series in 1992.

Plot

Mrs. Tittlemouse is a tale in which no humans play a part and one in which events are treated as though they have occurred since time immemorial and far from human observance. It is a simple story, and one likely to appeal to young children.

Mrs. Tittlemouse is a "most terribly tidy little mouse always sweeping and dusting the soft sandy floors" in the "yards and yards" of passages and storerooms, nut-cellars, and seed-cellars in her "funny house" amongst the roots of a hedge. She has a kitchen, a parlour, a pantry, a larder, and a bedroom where she keeps her dust-pan and brush next to her little box bed. She tries to keep her house tidy, but insect intruders leave dirty footprints on the floors and all sorts of messes about the place.

A beetle is shooed away, a ladybird is exorcised with "Fly away home! Your house is on fire!", and a spider inquiring after Miss Muffet is turned away with little ceremony. In a distant passage, Mrs. Tittlemouse meets Babbitty Bumble, a bumblebee who has taken up residence with three or four other bees in one of the empty storerooms. Mrs. Tittlemouse tries to pull out their nest but they buzz fiercely at her, and she retreats to deal with the matter after dinner.

In her parlour, she finds her toad neighbour Mr. Jackson sitting before the fire in her rocking chair. Mr. Jackson lives in "a drain below the hedge, in a very dirty wet ditch". His coat tails drip with water and he leaves wet footmarks on Mrs. Tittlemouse's parlour floor. She follows him about with a mop and dish-cloth.

Mrs. Tittlemouse allows Mr. Jackson to stay for dinner, but the food is not to his liking, and he rummages about the cupboard searching for the honey he can smell. He discovers a butterfly in the sugar bowl, but when he finds the bees, he makes a big mess pulling out their nest. Mrs. Tittlemouse fears she "shall go distracted" as a result of the turmoil and takes refuge in the nut-cellar. When she finally ventures forth, she discovers everybody has left but her house is a mess. She takes some moss, beeswax, and twigs to partly close up her front door to keep Mr. Jackson out. Exhausted, she goes to bed wondering if her house will ever be tidy again.

The fastidious little mouse spends a fortnight spring cleaning. She rubs the furniture with beeswax and polishes her little tin spoons, then holds a party for five other little wood-mice wearing their Regency finery. Mr. Jackson attends but is forced to sit outside because Mrs. Tittlemouse has narrowed her door. He takes no offence at being excluded from the parlour. Acorn-cupfuls of honeydew are passed through the window to him and he toasts Mrs. Tittlemouse's good health.

Background

Helen Beatrix Potter was born on 28 July 1866 in London to barrister Rupert William Potter and his wife Helen (Leech) Potter. She was educated by governesses and tutors, and passed a quiet and solitary childhood reading, painting, drawing, tending a nursery menagerie of small animals, and visiting museums and art exhibitions. Her interests in the natural world and country life were nurtured with holiday trips to Scotland, the English Lake District, and Camfield Place, the Hertfordshire home of her paternal grandparents.

Potter's adolescence was a quiet as her childhood. She grew into a spinsterish young woman whose parents groomed her to be a permanent resident and housekeeper in their home. She wanted to lead a useful life independent of her parents and considered a career in mycology, but the all-male scientific community regarded her as an amateur and she abandoned fungi. She continued to paint and draw, and experienced her first professional artistic success in 1890 when she sold six designs of humanised animals to a greeting card publisher.

In 1900, Potter revised a tale about a rabbit named Peter she had written for a child in 1893, and prepared a dummy book of it in imitation of Helen Bannerman's 1889 best-seller The Story of Little Black Sambo. Unable to find a buyer, she published the book for family and friends at her own expense in December 1901. Frederick Warne & Co. had earlier rejected the tale, but, anxious to compete in the booming small format children's book market, reconsidered and accepted it following the recommendation of their prominent children's book artist L. Leslie Brooke. Potter agreed to colour the pen and ink illustrations of the private edition, and chose the then-new Hentschel three-colour process for reproducing her watercolours. On 2 October 1902 The Tale of Peter Rabbit was released.

Potter continued to publish children's books with Warnes and used her sales profits and a small legacy from an aunt to buy Hill Top, a working farm of 34 acres (13.85 ha) in the Lake District in July 1905. On 25 August, Potter's fiancé and editor Norman Warne died suddenly; she became very depressed and was ill for many weeks, but rallied to complete the last few tales she had planned or discussed with him.

Illustrations

Mrs. Tittlemouse called upon Potter's keen observation of insects, arachnids, and amphibians, and her youthful experience drawing them. Their depictions in text and illustration reflect her understanding of insect anatomy, colouration, and behaviour; they are rendered with accuracy, humour, and true to their individual natures – she knew that toads only seek water during the spawning season, for example, and that they can smell honey. The spider and the butterfly are very much like those she drew from microscopic studies in the 1890s.

Potter's source for the wildlife and the insect drawings in Mrs. Tittlemouse were those she had executed in her early adulthood, either directly from nature or by observing specimens in the collections of the Victoria and Albert Museum. The interest in the book's illustrations lies in the microscopic accuracy of the insects rather than in any human qualities exhibited by Mrs. Tittlemouse or Mr. Jackson. Potter is uncharacteristically careless in the depiction of the insects however. They appear to be drawn for their own sake, or seem to be out of scale with the heroine, or to change scale without reason. The ladybird seems larger than Mrs. Tittlemouse, and the spider appears first larger than Mrs. Tittlemouse in one picture and then smaller in another. The bees are sometimes out of scale with both the toad and the mouse.

The nature artist and the fantasy artist in Potter are at odds: the mouse, the toad, and the insects share the same habitat but there seems no logical reason for the mouse and the toad to be humanised while the insects remain their natural selves. Logically, they should be humanised, too. It is possible Potter's carelessness in the details of Mrs. Tittlemouse can be attributed to a desire on her part to simply display her ability to draw from nature or to her interest in book production being supplanted by a growing interest in farming and local life and politics in Sawrey.

Merchandise

Potter asserted her tales would one day be nursery classics, and part of the process in making them so was marketing strategy. She was the first to exploit the commercial possibilities of her characters and tales with spinoffs such as a Peter Rabbit doll, an unpublished Peter Rabbit board game, and a Peter Rabbit nursery wallpaper between 1903 and 1905. Similar "side-shows" (as she termed the ancillary merchandise) were produced over the following two decades.

In 1947, Frederick Warne & Co. gave the John Beswick Factory of Longton, Staffordshire rights and licences to produce the Potter characters in porcelain. Mrs. Tittlemouse was among the first ten Beswick figurines produced in 1948, and was followed by Mr. Jackson in 1974, Mother Lady Bird in 1989, Babbitty Bumble in 1989, and another Mrs. Tittlemouse in 2000. A Mrs. Tittlemouse embossed plate was produced between 1982 and 1984.

Mrs. Tittlemouse appeared on the lid of a Huntley & Palmer biscuit tin in 1955, and in 1973, The Eden Toy Company of New York became the first and only American company to be granted licensing rights to manufacture stuffed Beatrix Potter characters in plush. Mrs. Tittlemouse was released in 1975. In 1975, Crummles of Poole, Dorset began manufacturing Beatrix Potter enamelled boxes, and eventually released a 32 millimetres (1.3 in) diameter enamelled box depicting Babbitty Bumble and Mrs. Tittlemouse holding her book.

In 1977, Schmid & Co. of Toronto and Randolph, Massachusetts was granted licensing rights to Beatrix Potter, and produced a Mrs. Tittlemouse music box playing "It's a Small World" the same year. A Mr. Jackson flat ceramic Christmas ornament followed in 1984, and a hanging ornament depicting Mrs. Tittlemouse in her little box bed in 1987.

Reprints and translations

As of 2010, all 23 of Potter's small format books remain in print, and are available as complete sets in presentation boxes. A 400-page omnibus edition is also available. First editions, early reprints, and limited edition facsimiles of the Mrs. Tittlemouse manuscript are available through antiquarian booksellers.

The English language editions of Potter's books still bore the Frederick Warne imprint in 2010, despite the company being sold to Penguin Books in 1983. In 1985 Penguin remade the book's printing plates from new photographs of the original drawings, and in 1987 released the entire collection as The Original and Authorized Edition.

Potter's books have been translated into almost 30 languages, including Greek and Russian. The Tale of Mrs. Tittlemouse was translated into Afrikaans in 1930 as Die Verhaal van Mevrou Piekfyn and into Dutch in 1970 as Het Verhaal die Minetje Miezemuis. Under licence to Fukuinkan-Shoten of Tokyo, in the 1970s The Tale of Mrs. Tittlemouse and 11 other stories were released in Japanese. In 1986, MacDonald observed that the Potter books had become a traditional part of childhood in both English-speaking lands and those in which the books had been translated.