South Carolina Declaration of Secession facts for kids

The South Carolina Declaration of Secession, formally known as the Declaration of the Immediate Causes Which Induce and Justify the Secession of South Carolina from the Federal Union, was a proclamation issued on December 24, 1860, by the government of South Carolina to explain its reasons for seceding from the United States. It followed the brief Ordinance of Secession that had been issued on December 20. The declaration is a product of a convention organized by the state's government in the month following the election of Abraham Lincoln as U.S. President, where it was drafted in a committee headed by Christopher Memminger. The declaration stated the primary reasoning behind South Carolina's declaring of secession from the U.S., which was described as "increasing hostility on the part of the non-slaveholding States to the Institution of Slavery". The Declaration states, in part, "A geographical line has been drawn across the Union, and all the States north of that line have united in the election of a man to the high office of President of the United States, whose opinions and purposes are hostile to slavery."

Background

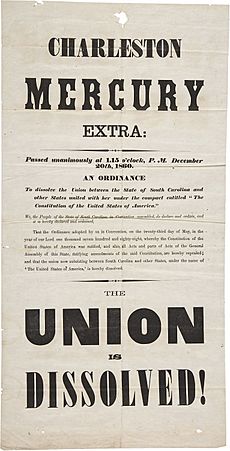

An official secession convention met in South Carolina following the November 1860 election of Abraham Lincoln as President of the United States, on a platform opposing the expansion of slavery into U.S. territories. On December 20, 1860, the convention issued an ordinance of secession announcing the state's withdrawal from the union. The ordinance was brief and legalistic in nature, containing no explanation of the reasoning behind the delegates' decision:

We, the People of the State of South Carolina, in Convention assembled do declare and ordain, and it is hereby declared and ordained, That the Ordinance adopted by us in Convention, on the twenty-third day of May in the year of our Lord One Thousand Seven hundred and eighty eight, whereby the Constitution of the United States of America was ratified, and also all Acts and parts of Acts of the General Assembly of this State, ratifying amendment of the said Constitution, are here by repealed; and that the union now subsisting between South Carolina and other States, under the name of "The United States of America," is hereby dissolved.

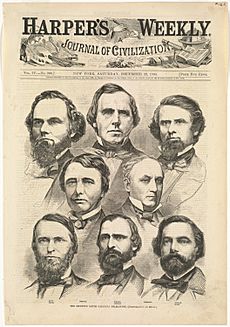

The convention had previously agreed to draft a separate statement that would summarize their justification and gave that task to a committee of seven members comprising Christopher G. Memminger (considered the primary author), F. H. Wardlaw, R. W. Barnwell, J. P. Richardson, B. H. Rutledge, J. E. Jenkins, and P. E. Duncan. The document they produced, the Declaration of the Immediate Causes Which Induce and Justify the Secession of South Carolina from the Federal Union, was adopted by the convention on December 24.

Synopsis

The opening portion of the declaration outlines the historical background of South Carolina and offers a legal justification for its secession. It asserts that the right of states to secede is implicit in the Constitution and this right was explicitly reaffirmed by South Carolina in 1852. The declaration states that the agreement between South Carolina and the United States is subject to the law of compact, which creates obligations on both parties and which revokes the agreement if either party fails to uphold its obligations.

The next section asserts that the government of the United States and of states within that government had failed to uphold their obligations to South Carolina. The specific issue stated was the refusal of some states to enforce the Fugitive Slave Act and clauses in the U.S. Constitution protecting slavery and the federal government's perceived role in attempting to abolish slavery.

The next section states that while these problems had existed for twenty-five years, the situation had recently become unacceptable due to the election of a President (this was Abraham Lincoln although he is not mentioned by name) who was planning to outlaw slavery. In reference to the failure of the northern states to uphold the Fugitive Slave Act, South Carolina states the primary reason for its secession:

The General Government, as the common agent, passed laws to carry into effect these stipulations of the States. For many years these laws were executed. But an increasing hostility on the part of the non-slaveholding States to the institution of slavery, has led to a disregard of their obligations, and the laws of the General Government have ceased to effect the objects of the Constitution.

Further on:

A geographical line has been drawn across the Union, and all the States north of that line have united in the election of a man to the high office of President of the United States, whose opinions and purposes are hostile to slavery.

The final section concludes with a statement that South Carolina had therefore seceded from the United States of America and was thus, no longer bound by its laws and authorities.

Legacy

While later claims have been made after the war's end that the South Carolinian decision to secede was prompted by other issues such as tariffs and taxes, these issues were not mentioned at all in the declaration. The primary focus of the declaration is the perceived violation of the Constitution by Northern states in not extraditing escaped slaves (as the U.S. Constitution required in Article IV, Section 2) and actively working to abolish slavery (which South Carolinian secessionists saw as Constitutionally guaranteed and protected). The main thrust of the argument was that since the U.S. Constitution, being a contract, had been violated by some parties (the Northern abolitionist states), the other parties (the Southern slave-holding states) were no longer bound by it. Georgia, Mississippi, and Texas offered similar declarations when they seceded, following South Carolina's example.

The declaration does not make a simple declaration of states' rights. It asserts that South Carolina was a sovereign state that had delegated only particular powers to the federal government by means of the U.S. Constitution. It furthermore protests other states' failure to uphold their obligations under the Constitution. The declaration emphasizes that the Constitution explicitly requires states to deliver "person(s) held in service or labor" back to their state of origin.

The declaration was the second of three documents to be officially issued by the South Carolina Secession Convention. The first was the Ordinance of Secession itself. The third was "The Address of the people of South Carolina, assembled in Convention, to the people of the Slaveholding States of the United States", written by Robert Barnwell Rhett, which called on other slave holding states to secede and join in forming a new nation. The convention resolved to print 15,000 copies of these three documents and distribute them to various parties.

The declaration was seen as analogous to the U.S. Declaration of Independence from 1776, however, it omitted the phrases that "all men are created equal", "that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights", and "consent of the governed". Professor and historian Harry V. Jaffa noted this omission as significant in his 2000 book, A New Birth of Freedom: Abraham Lincoln and the Coming of the Civil War:

South Carolina cites, loosely, but with substantial accuracy, some of the language of the original Declaration. That Declaration does say that it is the right of the people to abolish any form of government that becomes destructive of the ends for which it was established. But South Carolina does not repeat the preceding language in the earlier document: 'We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal'...

Jaffa states that South Carolina omitted references to human equality and consent of the governed, as due to their racist and pro-slavery views, secessionist South Carolinians did not believe in those ideals:

[G]overnments are legitimate only insofar as their "just powers" are derived "from the consent of the governed." All of the foregoing is omitted from South Carolina's declaration, for obvious reasons. In no sense could it have been said that the slaves in South Carolina were governed by powers derived from their consent. Nor could it be said that South Carolina was separating itself from the government of the Union because that government had become destructive of the ends for which it was established. South Carolina in 1860 had an entirely different idea of what the ends of government ought to be from that of 1776 or 1787. That difference can be summed up in the difference between holding slavery to be an evil, if possibly a necessary evil, and holding it to be a positive good.