Sinking of the RMS Lusitania facts for kids

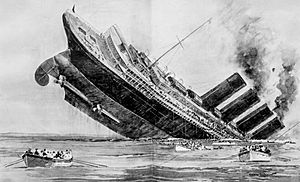

Painting of the sinking, from the German Federal Archives

|

|

| Date | 7 May 1915 |

|---|---|

| Time | 14:10 – 14:28 |

| Location | North Atlantic Ocean, near Old Head of Kinsale, Ireland |

| Coordinates | 51°25′N 8°33′W / 51.417°N 8.550°W |

| Cause | Torpedoed by German U-boat U-20 |

| Outcome |

|

The RMS Lusitania was a British-registered ocean liner that was torpedoed by an Imperial German Navy U-boat during the First World War on 7 May 1915, about 11 nautical miles (20 kilometres) off the Old Head of Kinsale, Ireland. The attack took place in the declared maritime war-zone around the UK, shortly after unrestricted submarine warfare against the ships of the United Kingdom had been announced by Germany following the Allied powers' implementation of a naval blockade against it and the other Central Powers. The passengers had been warned before departing New York of the danger of voyaging into the area in a British ship.

The Cunard liner was attacked by U-20 commanded by Kapitänleutnant Walther Schwieger. After the single torpedo struck, a second explosion occurred inside the ship, which then sank in only 18 minutes. The U-20’s mission was to torpedo warships and liners in the Lusitania’s area. 761 people survived out of the 1,266 passengers and 696 crew aboard, and 128 of the casualties were American citizens. The sinking turned public opinion in many countries against Germany. It also contributed to the American entry into the War two years later; images of the stricken liner were used heavily in US propaganda and military recruiting campaigns.

The contemporary investigations in both the United Kingdom and the United States into the precise causes of the ship's loss were obstructed by the needs of wartime secrecy and a propaganda campaign to ensure all blame fell upon Germany. At time of her sinking she was carrying 4,200,000 rounds of Remington .303 rifle/machine-gun cartridges, almost 5,000 shrapnel shell casings (for a total of some 50 tons), and 3,240 brass percussion artillery fuses, but argument over whether the ship was a legitimate military target raged back and forth throughout the war.

Several attempts have been made since the sinking to dive the wreck seeking information about how the ship sank. Military ammunition has been discovered in the wreck.

Contents

Background

When Lusitania was built, her construction and operating expenses were subsidized by the British government, with the provision that she could be converted to an Armed Merchant Cruiser if need be. At the outbreak of the First World War, the British Admiralty considered her for requisition as an armed merchant cruiser, and she was put on the official list of AMCs.

The Admiralty then cancelled their earlier decision and decided not to use her as an AMC after all; large liners such as Lusitania consumed enormous quantities of coal (910 tons/day, or 37.6 tons/hour) and became a serious drain on the Admiralty's fuel reserves, so express liners were deemed inappropriate for the role when smaller cruisers would do. They were also very distinctive; so smaller liners were used as transports instead. Lusitania remained on the official AMC list and was listed as an auxiliary cruiser in the 1914 edition of Jane's All the World's Fighting Ships, along with Mauretania.

At the outbreak of hostilities, fears for the safety of Lusitania and other great liners ran high. During the ship's first eastbound crossing after the war started, she was painted in a drab grey colour scheme in an attempt to mask her identity and make her more difficult to detect visually. When it turned out that the German Navy was kept in check by the Royal Navy, and their commerce threat almost entirely evaporated, it very soon seemed that the Atlantic was safe for ships like Lusitania, if the bookings justified the expense of keeping them in service.

Many of the large liners were laid up over the autumn and winter of 1914–1915, in part due to falling demand for passenger travel across the Atlantic, and in part to protect them from damage due to mines or other dangers. Among the most recognizable of these liners, some were eventually used as troop transports, while others became hospital ships. Lusitania remained in commercial service; although bookings aboard her were by no means strong during that autumn and winter, demand was strong enough to keep her in civilian service. Economizing measures were taken, however. One of these was the shutting down of her No. 4 boiler room to conserve coal and crew costs; this reduced her maximum speed from over 25 to 21 knots (46 to 39 km/h). Even so, she was the fastest first-class passenger liner left in commercial service.

With apparent dangers evaporating, the ship's disguised paint scheme was also dropped and she was returned to civilian colours. Her name was picked out in gilt, her funnels were repainted in their usual Cunard livery, and her superstructure was painted white again. One alteration was the addition of a bronze/gold coloured band around the base of the superstructure just above the black paint.

1915

The British established a naval blockade of Germany on the outbreak of war in August 1914, issuing a comprehensive list of contraband that included even foodstuffs, and in early November 1914 Britain declared the North Sea to be a war zone, with any ships entering the North Sea doing so at their own risk.

By early 1915, a new threat to British shipping began to materialise: U-boats (submarines). At first, the Germans used them only to attack naval vessels, and they achieved only occasional—but sometimes spectacular—successes. U-boats then began to attack merchant vessels at times, although almost always in accordance with the old cruiser rules. Desperate to gain an advantage on the Atlantic, the German government decided to step up its submarine campaign. On 4 February 1915, Germany declared the seas around the British Isles a war zone: from 18 February, Allied ships in the area would be sunk without warning. This was not wholly unrestricted submarine warfare, since efforts would be taken to avoid sinking neutral ships.

Lusitania was scheduled to arrive in Liverpool on 6 March 1915. The Admiralty issued her specific instructions on how to avoid submarines. Despite a severe shortage of destroyers, Admiral Henry Oliver ordered HMS Louis and Laverock to escort Lusitania, and took the further precaution of sending the Q ship Lyons to patrol Liverpool Bay. One of the destroyers' commanders attempted to discover the whereabouts of Lusitania by telephoning Cunard, who refused to give out any information and referred him to the Admiralty. At sea, the ships contacted Lusitania by radio, but did not have the codes used to communicate with merchant ships. Captain Daniel Dow of Lusitania refused to give his own position except in code, and since he was, in any case, some distance from the positions he gave, continued to Liverpool unescorted.

It seems that, in response to this new submarine threat, some alterations were made to Lusitania and her operation. She was ordered not to fly any flags in the war zone; a number of warnings, plus advice, were sent to the ship's commander to help him decide how to best protect his ship against the new threat and it also seems that her funnels were most likely painted a dark grey to help make her less visible to enemy submarines. There was no hope of disguising her actual identity, since her profile was so well known, and no attempt was made to paint out the ship's name at the prow.

Captain Dow, apparently suffering from stress from operating his ship in the war zone, and after a significant "false flag" controversy left the ship; Cunard later explained that he was "tired and really ill." He was replaced with a new commander, Captain William Thomas Turner, who had commanded Lusitania, Mauretania, and Aquitania in the years before the war.

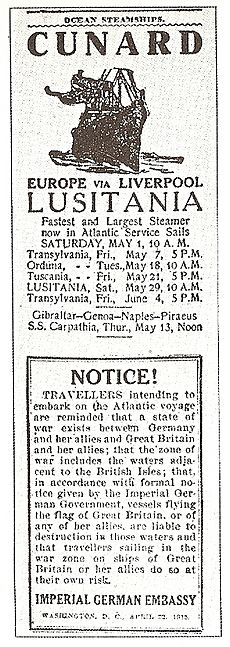

On 17 April 1915, Lusitania left Liverpool on her 201st transatlantic voyage, arriving in New York on 24 April. A group of German–Americans, hoping to avoid controversy if Lusitania were attacked by a U-boat, discussed their concerns with a representative of the German Embassy. The embassy decided to warn passengers before her next crossing not to sail aboard Lusitania, and on 22 April placed a warning advertisement in 50 American newspapers, including those in New York:

Notice!

Travellers intending to embark on the Atlantic voyage are reminded that a state of war exists between Germany and her allies and Great Britain and her allies; that the zone of war includes the waters adjacent to the British Isles; that, in accordance with formal notice given by the Imperial German Government, vessels flying the flag of Great Britain, or any of her allies, are liable to destruction in those waters and that travellers sailing in the war zone on the ships of Great Britain or her allies do so at their own risk.

Imperial German Embassy

Washington, D.C. 22 April 1915

This warning was printed adjacent to an advertisement for Lusitania's return voyage. The warning led to some agitation in the press and worried the ship's passengers and crew.

Final voyage

Departure

While many British passenger ships had been called into duty for the war effort, Lusitania remained on her regular route between Liverpool and New York City. She departed Pier 54 in New York on 1 May 1915 on her return trip to Liverpool with 1,959 people aboard. In addition to her crew of 694, she carried 1,265 passengers, mostly British nationals as well as a large number of Canadians, along with 159 Americans. Her First Class accommodations, for which she was well regarded on the North Atlantic run, were booked at just over half capacity at 290. Second Class was severely overbooked with 601 passengers, far exceeding the maximum capacity of 460. While a large number of small children and infants helped reduce the squeeze into the limited number of two- and four-berth cabins, the situation was rectified by allowing some Second Class passengers to occupy empty First Class cabins. In Third Class, the situation was considered to be the norm for an eastbound crossing, with only 373 travelling in accommodations designed for 1,186.

Captain Turner, known as "Bowler Bill" for his favourite shoreside headgear, had returned to his old command of Lusitania. He was commodore of the Cunard Line and a highly experienced master mariner, and had relieved Daniel Dow, the ship's regular captain. Dow had been instructed by his chairman, Alfred Booth, to take some leave, due to the stress of captaining the ship in U-boat infested sea lanes and for his protestations that the ship should not become an armed merchant cruiser, making her a prime target for German forces. Turner tried to calm the passengers by explaining that the ship's speed made her safe from attack by submarine. However, Cunard shut down one of the ship's four boiler rooms to reduce costs on sparsely subscribed wartime voyages, reducing her top speed from 25.5 to around 22 knots.

Lusitania steamed out of New York at noon on 1 May, two hours behind schedule, because of a last-minute transfer of forty-one passengers and crew from the recently requisitioned Cameronia. Shortly after departure three German-speaking men were found on board hiding in a steward's pantry. Detective Inspector William Pierpoint of the Liverpool police, who was travelling in the guise of a first-class passenger, interrogated them before locking them in the cells for further questioning when the ship reached Liverpool. Also among the crew was an Englishman, Neal Leach, who had been working as a tutor in Germany before the war. Leach had been interned but later released by Germany. The German embassy in Washington was notified about Leach's arrival in America, where he met known German agents. Leach and the three German stowaways went down with the ship. They had probably been tasked with spying on Lusitania and her cargo. Most probably, Pierpoint, who survived the sinking, would already have been informed about Leach.

Submarine activity

As the liner steamed across the ocean, the British Admiralty had been tracking the movements of U-20, commanded by Kapitänleutnant Walther Schwieger, through wireless intercepts and radio direction finding. The submarine left Borkum on 30 April, heading north-west across the North Sea. On 2 May, she had reached Peterhead and proceeded around the north of Scotland and Ireland, and then along the western and southern coasts of Ireland, to enter the Irish Sea from the south. Although the submarine's departure, destination, and expected arrival time were known to Room 40 in the Admiralty, the activities of the decoding department were considered so secret that they were unknown even to the normal intelligence division which tracked enemy ships or to the trade division responsible for warning merchant vessels. Only the very highest officers in the Admiralty saw the information and passed on warnings only when they felt it essential.

On 27 March, Room 40 had intercepted a message which clearly demonstrated that the Germans had broken the code used to pass messages to British merchant ships. Cruisers protecting merchant ships were warned not to use the code to give directions to shipping because it could just as easily attract enemy submarines as steering ships away from them. However, Queenstown (now Cobh) was not given this warning and continued to give directions in the compromised code, which was not changed until after Lusitania's sinking. At this time, the Royal Navy was significantly involved with operations leading up to the landings at Gallipoli, and the intelligence department had been undertaking a program of misinformation to convince Germany to expect an attack on her northern coast. As part of this, ordinary cross-channel traffic to the Netherlands was halted from 19 April and false reports were leaked about troop ship movements from ports on Britain's western and southern coasts. This led to a demand from the German army for offensive action against the expected troop movements and consequently, a surge in German submarine activity on the British west coast. The fleet was warned to expect additional submarines, but this warning was not passed on to those sections of the navy dealing with merchant vessels. The return of the battleship Orion from Devonport to Scotland was delayed until 4 May and she was given orders to stay 100 nautical miles (190 km) from the Irish coast.

On 5 May, U-20 stopped a merchant schooner, Earl of Lathom, off the Old Head of Kinsale, examined her papers, then ordered her crew to leave before sinking the schooner with gunfire. On 6 May, U-20 fired a torpedo at Cayo Romano, a British steamer originating from Cuba flying a neutral flag, off Fastnet Rock, narrowly missing by a few feet. At 22:30 on 5 May, the Royal Navy sent an uncoded warning to all ships – "Submarines active off the south coast of Ireland" – and at midnight an addition was made to the regular nightly warnings, "submarine off Fastnet". On 6 May U-20 sank the 6,000 ton steamer Candidate. It then failed to get off a shot at the 16,000 ton liner Arabic, because although she kept a straight course the liner was too fast, but then sank another 6,000 ton British cargo ship flying no flag, Centurion, all in the region of the Coningbeg light ship. The specific mention of a submarine was dropped from the midnight broadcast on 6–7 May as news of the new sinkings had not yet reached the navy at Queenstown, and it was correctly assumed that there was no longer a submarine at Fastnet.

Captain Turner of Lusitania was given a warning message twice on the evening of 6 May, and took what he felt were prudent precautions. That evening a Seamen's Charities fund concert took place throughout the ship and the captain was obliged to attend the event in the first-class lounge.

At about 11:00 on 7 May, the Admiralty radioed another warning to all ships, probably as a result of a request by Alfred Booth, who was concerned about Lusitania: "U-boats active in southern part of Irish Channel. Last heard of twenty miles south of Coningbeg Light Vessel". Booth and all of Liverpool had received news of the sinkings, which the Admiralty had known about by at least 3:00 that morning. Turner adjusted his heading northeast, not knowing that this report related to events of the previous day and apparently thinking submarines would be more likely to keep to the open sea, so that Lusitania would be safer close to land. At 13:00 another message was received, "Submarine five miles south of Cape Clear proceeding west when sighted at 10:00 am". This report was inaccurate as no submarine had been at that location, but gave the impression that at least one submarine had been safely passed.

U-20 was low on fuel and had only three torpedoes left. On the morning of 7 May, visibility was poor and Schwieger decided to head for home. He submerged at 11:00 after sighting a fishing boat which he believed might be a British patrol and shortly after was passed while still submerged by a ship at high speed. This was the cruiser Juno (1895) returning to Queenstown, travelling fast and zig-zagging having received warning of submarine activity off Queenstown at 07:45. The Admiralty considered these old cruisers highly vulnerable to submarines, and indeed Schwieger attempted to target the ship.

Sinking

On the morning of 6 May, Lusitania was 750 nautical miles (1,390 km) west of southern Ireland. By 05:00 on 7 May, she reached a point 120 nautical miles (220 km) west-southwest of Fastnet Rock (off the southern tip of Ireland), where she met the patrolling boarding vessel Partridge. By 06:00, heavy fog had arrived and extra lookouts were posted. Upon entering the war zone, Captain Turner had 22 lifeboats swung out as a precaution so they could be launched more quickly if needed. As the ship came closer to Ireland, Captain Turner ordered depth soundings to be made and at 08:00 for speed to be reduced to eighteen knots, then to 15 knots and for the foghorn to be sounded. Some of the passengers were disturbed that the ship appeared to be advertising her presence. By 10:00, the fog began to lift, by noon it had been replaced by bright sunshine over a clear smooth sea and speed increased to 18 knots.

U-20 surfaced again at 12:45 as visibility was now excellent. At 13:20, something was sighted and Schwieger was summoned to the conning tower: at first it appeared to be several ships because of the number of funnels and masts, but this resolved into one large steamer appearing over the horizon. At 13:25, the submarine submerged to periscope depth of 11 metres and set a course to intercept the liner at her maximum submerged speed of 9 knots. When the ships had closed to 2 nautical miles (3.7 km) Lusitania turned away, Schwieger feared he had lost his target, but she turned again, this time onto a near ideal course to bring her into position for an attack. At 14:10, with the target at 700m range he ordered one gyroscopic torpedo to be fired, set to run at a depth of three metres.

In Schwieger's own words, recorded in the log of U-20:

Torpedo hits starboard side right behind the bridge. An unusually heavy detonation takes place with a very strong explosive cloud. The explosion of the torpedo must have been followed by a second one [boiler or coal or powder?]... The ship stops immediately and heels over to starboard very quickly, immersing simultaneously at the bow... the name Lusitania becomes visible in golden letters.

U-20's torpedo officer, Raimund Weisbach, viewed the destruction through the vessel's periscope and felt the explosion was unusually severe. Within six minutes, Lusitania's forecastle began to submerge. Though Schwieger states the torpedo hit beneath the bridge, survivor testimony, including that of Captain Turner, gave a number of different locations: some stated it was between the first and second funnels, others between the third and fourth, and one claimed it struck below the capstan.

On board the Lusitania, Leslie Morton, an eighteen-year-old lookout at the bow, had spotted thin lines of foam racing toward the ship. He shouted, "Torpedoes coming on the starboard side!" through a megaphone, thinking the bubbles came from two projectiles, not one. The torpedo struck Lusitania abaft the bridge, sending a plume of water upward which knocked Lifeboat No. 5 off its davits and a geyser of steel plating, coal smoke, cinders, and debris high above the deck "It sounded like a million-ton hammer hitting a steam boiler a hundred feet high", one passenger said. A second, more powerful explosion followed, ringing throughout the ship, and thick grey smoke began to pour out of the funnels and ventilator cowls that led deep into the boiler rooms. Schwieger's log entries attest that he launched only one torpedo. Some doubt the validity of this claim, contending that the German government subsequently altered the published fair copy of Schwieger's log, but accounts from other U-20 crew members corroborate it. The entries were also consistent with intercepted radio reports sent to Germany by U-20 once she had returned to the North Sea, before any possibility of an official coverup.

-

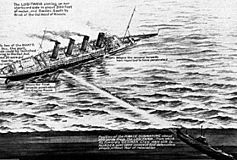

German drawing of Lusitania being torpedoed which incorrectly depicts the torpedo hitting the port side of ship

-

Lusitania is shown sinking as Irish fishermen race to the rescue. In fact, the launching of the lifeboats was more chaotic

At 14:12, Captain Turner had Quartermaster Johnston stationed at the ship's wheel to steer 'hard-a-starboard' towards the Irish coast, which Johnston confirmed, but the ship could not be steadied and rapidly ceased to respond to the wheel. Turner signalled for the engines to be reversed to halt the ship, but although the signal was received in the engine room, nothing could be done. Steam pressure had collapsed from 195 psi before the explosion, to 50 psi and falling afterwards, meaning Lusitania could not be steered or stopped to counteract the list or to beach herself. Lusitania's wireless operator sent out an immediate SOS, which was acknowledged by a coastal wireless station. Shortly afterward he transmitted the ship's position, 10 nautical miles (19 km) south of the Old Head of Kinsale. At 14:14, electrical power failed, plunging the cavernous interior of the ship into darkness. Radio signals continued on emergency batteries, but electric lifts failed, trapping crew members in the forward cargo hold who had been preparing luggage to go ashore at Liverpool later that evening; it was these seamen precisely who were to report to muster stations to launch lifeboats in the event of a sinking; bulkhead doors, that were closed as a precaution before the attack, could not be reopened to release trapped men. The rudder became inoperable with the loss of power as well, meaning the ship could not be steered to counteract the list or to beach herself. Few testimonies report passengers trapped in the two central elevators, though one saloon passenger claimed to have seen the lifts stuck between the boat deck and the deck below while passing through the First Class entrance.

About one minute after the electrical power failed, Captain Turner gave the order to abandon ship. Water had flooded the ship's starboard longitudinal compartments, causing a 15-degree list to starboard.

Lusitania's severe starboard list complicated the launch of her lifeboats. Ten minutes after the torpedo struck, when she had slowed enough to start putting boats in the water, the lifeboats on the starboard side swung out too far to step aboard safely. While it was still possible to board the lifeboats on the port side, lowering them presented a different problem. As was typical for the period, the hull plates of Lusitania were riveted, and as the lifeboats were lowered they dragged on the inch-high rivets, which threatened to seriously damage or capsize the boats before they landed in the water.

Many lifeboats overturned while loading or lowering, spilling passengers into the sea and others were overturned by the ship's motion when they hit the water. It has been claimed that some boats, because of the negligence of some officers, crashed down onto the deck, crushing other passengers, and sliding down towards the bridge. This has been disputed by passenger and crew testimony. Some untrained crewmen would lose their grip on handheld ropes used to lower the lifeboats while trying to lower the boats into the ocean, spilling their occupants into the sea. Others tipped on launch as some panicking people jumped into the boat. Lusitania had 48 lifeboats, more than enough for all the crew and passengers, but only 6 were successfully lowered, all from the starboard side. Lifeboat 1 overturned as it was being lowered, spilling its original occupants into the sea, but it managed to right itself shortly afterwards and was later filled with people from in the water. Lifeboats 9 (5 people on board) and 11 (7 people on board) managed to reach the water safely with a few people, but both later picked up many swimmers. Lifeboats 13 and 15 also safely reached the water, overloaded with around 150 people. Finally, Lifeboat 21 (52 people on board) reached the water safely and cleared the ship moments before her final plunge. A few of her collapsible lifeboats washed off her decks as she sank and provided flotation for some survivors.

Two lifeboats on the port side cleared the ship as well. Lifeboat 14 (11 people on board) was lowered and launched safely, but because the boat plug was not in place, it filled with seawater and sank almost immediately after reaching the water. Later, Lifeboat 2 floated away from the ship with new occupants (its previous ones having been spilled into the sea when they upset the boat) after they removed a rope and one of the ship's "tentacle-like" funnel stays. They rowed away shortly before the ship sank.

There was panic and disorder on the starboard side of the deck. Schwieger had been observing this through U-20's periscope, and by 14:25, he dropped the periscope and headed out to sea. Later in the war, Schwieger was killed in action when, as he commanded U-88 the vessel struck a British mine and sank on 5 September 1917, north of Terschelling. There were no survivors from U-88's sinking.

Surviving passengers on the port side of the deck, however, paint a calmer picture. Many, including author Charles Lauriat, who published his account of the disaster, stated that a few passengers climbed into the early portside lifeboats before being ordered out by Staff Captain James Anderson, who proclaimed, "This ship will not sink" and reassured those nearby that the liner had "touched bottom" and would stay afloat. In reality, he had ordered the crew to wait and fill Lusitania's portside ballast tanks with seawater to even the ship's trim so the lifeboats could be lowered safely. As a result, few boats on the port side were launched, none under Anderson's supervision.

Captain Turner was on the deck near the bridge clutching the ship's logbook and charts when a wave swept upward towards the bridge and the rest of the ship's forward superstructure, knocking him overboard into the sea. He managed to swim and find a chair floating in the water which he clung to. He survived, having been pulled unconscious from the water after spending three hours there. Lusitania's bow slammed into the bottom about 100 metres (330 ft) below at a shallow angle because of her forward momentum as she sank. Along the way, some boilers exploded and the ship returned briefly to an even keel. Turner's last navigational fix had been only two minutes before the torpedoing, and he was able to remember the ship's speed and bearing at the moment of the sinking. This was accurate enough to locate the wreck after the war. The ship travelled about two nautical miles (4 km) from the time of the torpedoing to her final resting place, leaving a trail of debris and people behind. After her bow sank completely, Lusitania's stern rose out of the water, enough for her propellers to be seen, and went under. As the tips of Lusitania's four, 70-foot-tall funnels dipped beneath the surface, they formed whirlpools which dragged nearby swimmers down with the ship. Her masts and rigging were the last to disappear.

Lusitania sank in only 18 minutes, at a distance of 11.5 nautical miles (21 km) off the Old Head of Kinsale. Despite being relatively close to shore, it took several hours for help to arrive from the Irish coast. By the time help arrived, however, many in the 52 °F (11 °C) water had succumbed to the cold. By the days' end, 764 passengers and crew from Lusitania had been rescued and landed at Queenstown. The final death toll for the disaster came to a catastrophic number. Of the 1,959 passengers and crew aboard Lusitania at the time of her sinking, 1,199 had been lost.

Two days before, U-20 had sunk Earl of Lathom, but first allowed the crew to escape in boats. According to international maritime law, any military vessel stopping an unarmed civilian ship was required to allow those on board time to escape before sinking it. The conventions had been drawn up in a time before the invention of the submarine and took no account of the severe risk a small vessel, such as a submarine, faced if it gave up the advantage of a surprise attack. Schwieger could have allowed the crew and passengers of Lusitania to take to the boats, but he considered the danger of being rammed or fired upon by deck guns too great. Merchant ships had, in fact, been advised to steer directly at any U-boat that surfaced. A cash bonus had been offered for any that were sunk, though the advice was carefully worded so as not to amount to an order to ram. This feat would be accomplished only once during the war by a commercial vessel when in 1918 the White Star Liner HMT Olympic, sister ship to the Titanic, rammed SM U-103 in the English Channel, sinking the submarine.

According to Bailey and Ryan, Lusitania was travelling without any flag and her name painted over with darkish dye.

One story—an urban legend—states that when Lieutenant Schwieger of U-20 gave the order to fire, his quartermaster, Charles Voegele, would not take part in an attack on women and children, and refused to pass on the order to the torpedo room – a decision for which he was court-martialed and imprisoned at Kiel until the end of the war. This rumour persisted from 1972, when the French daily paper Le Monde published a letter to the editor. Despite seemingly putting an end to this rumor, Voegele's alleged hesitation was depicted in the torpedoing scene of the 2007 docudrama Sinking of the Lusitania: Terror at Sea.

Last survivors

The last survivor was Audrey Warren Lawson-Johnston (née Pearl), who was born in New York City on 15 February 1915. She was the fourth of six children (the youngest two born after the disaster) born to Major Frederic "Frank" Warren Pearl (1869–1952) and Amy Lea (née Duncan; 1880–1964). She was only three months old when she boarded Lusitania in New York with her parents, three siblings, and two nurses – and due to her age had no first hand recollection of the disaster. She and her brother Stuart (age 5) were saved by their British nursemaid Alice Maud Lines, then 18 years old, who jumped off the boat deck and escaped in a lifeboat. Her parents also survived, but her sisters Amy (age 3) and Susan (age 14 months) died. Pearl married Hugh de Beauchamp Lawson-Johnston, second son of George Lawson Johnston, 1st Baron Luke, on 18 July 1946. They had three children and lived in Melchbourne, Bedfordshire. Hugh was Sheriff of Bedfordshire in 1961. Johnston gifted an inshore lifeboat, Amy Lea, to New Quay Lifeboat Station in 2004 in memory of her mother. Audrey Johnston died on 11 January 2011, a month before her 96th birthday.

The last American survivor was Barbara McDermott (born Barbara Winifred Anderson in Connecticut on 15 June 1912, to Roland Anderson and Emily Pybus). She was almost three years old at the time of the sinking. Her father worked as a draftsman for an ammunitions factory in south-western Connecticut. He was unable to accompany his wife and daughter on Lusitania as the First World War had created high demands for ammunition manufacturing at the factory where he worked. Barbara recalled being in the ship's dining room eating dessert when the torpedo hit. She remembered holding onto her spoon as she saw fellow passengers running about the badly damaged ship. In the midst of chaos, Barbara was separated from her mother and loaded into Lifeboat No. 15. Barbara later learned that her mother fell into the sea but was rescued and placed into the same lifeboat as her daughter. Neither Barbara nor her mother was seriously injured. After their rescue, Barbara and her mother travelled to Darlington, County Durham, England, to live with Barbara's maternal grandmother. Barbara's mother died on 22 March 1917 at the age of 28. Two years later, Barbara left Britain and travelled back to the United States aboard Mauretania and arrived in New York City on 26 December 1919. Barbara died on 12 April 2008 in Wallingford, Connecticut, at the age of 95.

Cultural legacy

Film

There is no footage of the sinking.

- Animation pioneer Winsor McCay spent nearly two years animating the disaster for his film The Sinking of the Lusitania (1918). At 12 minutes, it was the longest animated film on record at the time. It was also the earliest-known dramatic animation.

- The docudrama Sinking of the Lusitania: Terror at Sea (2007) depicts the last voyage of the Lusitania and the political and military decisions that led to the sinking.

- The National Geographic documentary Dark Secrets of the Lusitania (2012) describes an expedition investigating the wreck made by Greg Bemis and a crew of divers in 2011.

Wreck artefacts

- The Merseyside Maritime Museum in Liverpool, which was the home port of the Cunard line, has a large exhibit about Lusitania sinking. In 1982 one of the ship's four-bladed propellers was raised from the wreck, it is now on permanent display at the Albert Dock.

- A propeller from the wreck is on display at the Hilton Anatole in Dallas, Texas.

- Another salvaged propeller from the ship was melted down to create golf clubs in the 1980s.

- A lifeboat davit and some other artefacts are displayed at the Lusitania Museum & Old Head Signal Tower on Old Head of Kinsale.

- The original builder's model of Lusitania, repainted after the sinking to represent RMS Mauretania, is displayed at the Maritime Museum of the Atlantic in Halifax, Nova Scotia.

Literature

- The events of Agatha Christie's 1922 novel The Secret Adversary are set off by the sinking of Lusitania.

- A majority of Kim Izzo's Seven Days in May (2017) takes place aboard the Lusitania. The historical fiction alternates between a group of people on board, including Alfred Vanderbilt and Charles Frohman, and in a secret room in Whitehall in London, where coded messages are being intercepted.

- The Glass Ocean (2019), written by Karen White, Lauren Willig and Beatriz Williams, rotates narrators and time periods. One of the storylines takes place aboard the Lusitania. It is a fictional account from a passengers' perspective, and weaves in with storylines told in 2013.

- David Butler's novel Lusitania (1982) is a fictionalised account of the sinking and events leading up to it.

- Erik Larson's non-fiction book, Dead Wake: The Last Crossing of the Lusitania (2015), describes the ship's final voyage from multiple perspectives.

- H.P. Lovecraft's first published book was The Crime of Crimes: Lusitania 1915 (published in Wales), a poem on the sinking of the vessel.

- Graham Masterton's 2002 novel A Terrible Beauty (Katie Maguire No. 1) (published as Black River in France) includes a scene that claims to find evidence of how British intelligence informed the German Admiralty that a wanted murderer was aboard the ship, thus encouraging them to carry out the sinking.

- The sinking was the inspiration for Michael Morpurgo's novel Listen to the Moon (2014).

- Nora Roberts' novel Three Fates (2002) begins with the sinking of the Lusitania from the point of view of a fictitious passenger, Felix Greenfield, who survives. The plot centers around the descendants of Greenfield and another fictitious passenger, Henry W. Wyley, (who perished in the attack) and their quest to find a set of priceless statues called The Three Fates.

- Robert H. Pilpel's novel To the Honor of the Fleet (1979) included the sinking of Lusitania as an important plot point concerning the adventures of two U.S. Navy intelligence officers, each attached to either the British Royal Navy or the Imperial German Navy, prior to the Battle of Jutland and the American entry into the war.

- In the first chapter of Trevor D'Silva's debut novel Fateful Decisions (2017), the story begins on the Lusitania, where the protagonist Rachel Williams meets two friends who fall in love with her. One of them saves her when the ship is torpedoed. She later makes a decision to marry one of them when they propose to her after meeting at a fund raiser when America enters World War I. Her decision has good and devastating consequences for herself, her family and strangers, as their lives get entangled in world events including World War II.

Music

- English composer Frank Bridge had strong pacifist convictions and was deeply disturbed by the First World War. In 1915, he wrote his Lament (for Catherine, aged 9 "Lusitania" 1915), for string orchestra, as a memorial to the sinking of the ship. The piece was premiered by the New Queen's Hall Orchestra, conducted by the composer, on 15 September, at the 1915 Proms, as part of a programme of "Popular Italian music", the rest of which was conducted by Henry Wood.

- Charles Ives's Orchestral Set No. 2 concludes with a movement entitled, From Hanover Square North, at the End of a Tragic Day, the Voice of the People Again Arose. It recounts Ives's experience waiting for an elevated train in New York City as the news of the sinking of Lusitania came through. The passengers assembled on the platform began singing "In The Sweet By and By" in time to a barrel organ which was playing the tune. Echoes of their voices can be heard at the start of the music, and the hymn tune itself appears at the end.

- A popular song, "As the Lusitania Went Down" (1915) by Arthur J. Lamb and F. Henri Klickmann was published by C. K. Root & Co. of Chicago and New York. It was described by The Music Trade Review on 29 May 1915 as "One of the most interesting of the songs that have made their appearance in the commemoration of the Lusitania disaster."

- The song "When the Lusitania Went Down" (1915) by Charles McCarron and Nat Vincent was published by Leo Feist, in New York. Columbia Records issued a recording sung by baritone Herbert Stuart (otherwise known as Albert Wiederhold) and with orchestra accompaniment, as an 80 rpm disc.

- The song "Lusitania" from American black metal band Minenwerfer, on their second album Nihilistischen.

- "Lusitania" from American singer-songwriter Andrew Bird. The song features vocals by Annie Clark of St. Vincent.

- The song "Dead Wake" from post-hardcore band Thrice.

Wreck site

The wreck of Lusitania lies on her starboard side at an approximately 30-degree angle in 305 feet (93 metres) of sea water. She is severely collapsed onto her starboard side as a result of the force with which she slammed into the sea floor, and over decades, Lusitania has deteriorated significantly faster than Titanic because of the corrosion in the winter tides. The keel has an "unusual curvature", in a boomerang shape, which may be related to a lack of strength from the loss of her superstructure. The beam is reduced with the funnels missing, presumably due to deterioration. The bow is the most prominent portion of the wreck with the stern damaged from the removal of three of the four propellers by Oceaneering International in 1982 for display.

Some of the prominent features on Lusitania include her still-legible name, some bollards with the ropes still intact, pieces of the ruined promenade deck, some portholes, the prow and the remaining propeller. Recent expeditions to the wreck have revealed that Lusitania is in surprisingly poor condition compared to Titanic, as her hull has already started to collapse.

See also

In Spanish: Hundimiento del RMS Lusitania para niños

In Spanish: Hundimiento del RMS Lusitania para niños

- List by death toll of ships sunk by submarines