Sherlock Holmes facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Sherlock Holmes |

|

|---|---|

| Sherlock Holmes character | |

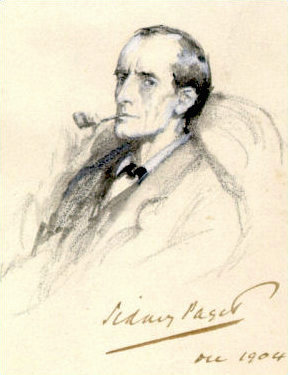

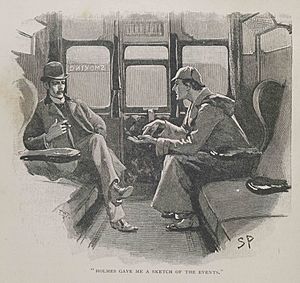

Sherlock Holmes in a 1904 illustration by Sidney Paget

|

|

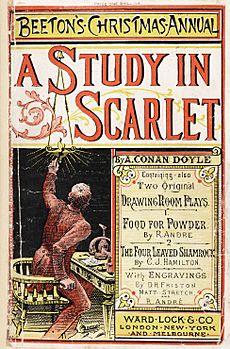

| First appearance | A Study in Scarlet (1887) |

| Last appearance | "The Adventure of Shoscombe Old Place" (1927, canon) |

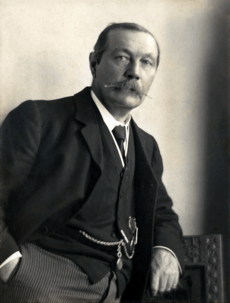

| Created by | Sir Arthur Conan Doyle |

| Information | |

| Occupation | Consulting private detective |

| Family | Mycroft Holmes (brother) |

| Nationality | British |

Sherlock Holmes is a fictional detective created by British author Sir Arthur Conan Doyle. Referring to himself as a "consulting detective" in the stories, Holmes is known for his proficiency with observation, deduction, forensic science and logical reasoning that borders on the fantastic, which he employs when investigating cases for a wide variety of clients, including Scotland Yard.

First appearing in print in 1887's A Study in Scarlet, the character's popularity became widespread with the first series of short stories in The Strand Magazine, beginning with "A Scandal in Bohemia" in 1891; additional tales appeared from then until 1927, eventually totalling four novels and 56 short stories. All but one are set in the Victorian or Edwardian eras, between about 1880 and 1914. Most are narrated by the character of Holmes's friend and biographer Dr. John H. Watson, who usually accompanies Holmes during his investigations and often shares quarters with him at the address of 221B Baker Street, London, where many of the stories begin.

Though not the first fictional detective, Sherlock Holmes is arguably the best known. By the 1990s, there were already over 25,000 stage adaptations, films, television productions and publications featuring the detective, and Guinness World Records lists him as the most portrayed literary human character in film and television history. Holmes's popularity and fame are such that many have believed him to be not a fictional character but a real individual; numerous literary and fan societies have been founded on this pretence. Avid readers of the Holmes stories helped create the modern practice of fandom. The character and stories have had a profound and lasting effect on mystery writing and popular culture as a whole, with the original tales as well as thousands written by authors other than Conan Doyle being adapted into stage and radio plays, television, films, video games, and other media for over one hundred years.

Inspiration for the character

Edgar Allan Poe's C. Auguste Dupin is generally acknowledged as the first detective in fiction and served as the prototype for many later characters, including Holmes. Conan Doyle once wrote, "Each [of Poe's detective stories] is a root from which a whole literature has developed ... Where was the detective story until Poe breathed the breath of life into it?" Similarly, the stories of Émile Gaboriau's Monsieur Lecoq were extremely popular at the time Conan Doyle began writing Holmes, and Holmes's speech and behaviour sometimes follow those of Lecoq. Doyle has his main characters discuss these literary antecedents near the beginning of A Study in Scarlet, which is set soon after Watson is first introduced to Holmes. Watson attempts to compliment Holmes by comparing him to Dupin, to which Holmes replies that he found Dupin to be "a very inferior fellow" and Lecoq to be "a miserable bungler".

Conan Doyle repeatedly said that Holmes was inspired by the real-life figure of Joseph Bell, a surgeon at the Royal Infirmary of Edinburgh, whom Conan Doyle met in 1877 and had worked for as a clerk. Like Holmes, Bell was noted for drawing broad conclusions from minute observations. However, he later wrote to Conan Doyle: "You are yourself Sherlock Holmes and well you know it". Sir Henry Littlejohn, Chair of Medical Jurisprudence at the University of Edinburgh Medical School, is also cited as an inspiration for Holmes. Littlejohn, who was also Police Surgeon and Medical Officer of Health in Edinburgh, provided Conan Doyle with a link between medical investigation and the detection of crime.

Other possible inspirations have been proposed, though never acknowledged by Doyle, such as Maximilien Heller, by French author Henry Cauvain. In this 1871 novel (sixteen years before the first appearance of Sherlock Holmes), Henry Cauvain imagined a depressed, anti-social polymath detective, operating in Paris. It is not known if Conan Doyle read the novel, but he was fluent in French. Similarly, Michael Harrison suggested that a German self-styled "consulting detective" named Walter Scherer may have been the model for Holmes.

Fictional character biography

Family and early life

Details of Sherlock Holmes's life in Conan Doyle's stories are scarce and often vague. Nevertheless, mentions of his early life and extended family paint a loose biographical picture of the detective.

A statement of Holmes's age in "His Last Bow" places his year of birth at 1854; the story, set in August 1914, describes him as sixty years of age. His parents are not mentioned, although Holmes mentions that his "ancestors" were "country squires". In "The Adventure of the Greek Interpreter", he claims that his grandmother was sister to the French artist Vernet, without clarifying whether this was Claude Joseph, Carle, or Horace Vernet. Holmes's brother Mycroft, seven years his senior, is a government official. Mycroft has a unique civil service position as a kind of human database for all aspects of government policy. Sherlock describes his brother as the more intelligent of the two, but notes that Mycroft lacks any interest in physical investigation, preferring to spend his time at the Diogenes Club.

Holmes says that he first developed his methods of deduction as an undergraduate; his earliest cases, which he pursued as an amateur, came from fellow university students. A meeting with a classmate's father led him to adopt detection as a profession.

Life with Watson

Financial difficulties lead Holmes and Dr. Watson to share rooms together at 221B Baker Street, London. Their residence is maintained by their landlady, Mrs. Hudson. Holmes works as a detective for twenty-three years, with Watson assisting him for seventeen of those years. Most of the stories are frame narratives written from Watson's point of view, as summaries of the detective's most interesting cases. Holmes frequently calls Watson's records of Holmes's cases sensational and populist, suggesting that they fail to accurately and objectively report the "science" of his craft:

Detection is, or ought to be, an exact science and should be treated in the same cold and unemotional manner. You have attempted to tinge it [A Study in Scarlet] with romanticism, which produces much the same effect as if you worked a love-story or an elopement into the fifth proposition of Euclid. ... Some facts should be suppressed, or, at least, a just sense of proportion should be observed in treating them. The only point in the case which deserved mention was the curious analytical reasoning from effects to causes, by which I succeeded in unravelling it.

Nevertheless, Holmes's friendship with Watson is his most significant relationship. When Watson is injured by a bullet, although the wound turns out to be "quite superficial", Watson is moved by Holmes's reaction:

It was worth a wound; it was worth many wounds; to know the depth of loyalty and love which lay behind that cold mask. The clear, hard eyes were dimmed for a moment, and the firm lips were shaking. For the one and only time I caught a glimpse of a great heart as well as of a great brain. All my years of humble but single-minded service culminated in that moment of revelation.

After confirming Watson's assessment of the wound, Holmes makes it clear to their opponent that the man would not have left the room alive if he genuinely had killed Watson. When Holmes recorded a case or two himself, he was forced to concede that he could more easily understand the need to write it in a manner that would appeal to the public rather than his intention to focus on his own technical skill.

Practice

Holmes's clients vary from the most powerful monarchs and governments of Europe, to wealthy aristocrats and industrialists, to impoverished pawnbrokers and governesses. He is known only in select professional circles at the beginning of the first story, but is already collaborating with Scotland Yard. However, his continued work and the publication of Watson's stories raise Holmes's profile, and he rapidly becomes well known as a detective; so many clients ask for his help instead of (or in addition to) that of the police that, Watson writes, by 1887 "Europe was ringing with his name" and by 1895 Holmes has "an immense practice". Police outside London ask Holmes for assistance if he is nearby. A Prime Minister and the King of Bohemia visit 221B Baker Street in person to request Holmes's assistance; the President of France awards him the Legion of Honour for capturing an assassin; the King of Scandinavia is a client; and he aids the Vatican at least twice. The detective acts on behalf of the British government in matters of national security several times, and declines a knighthood "for services which may perhaps some day be described". However, he does not actively seek fame and is usually content to let the police take public credit for his work.

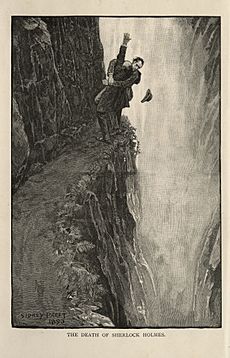

The Great Hiatus

The first set of Holmes stories was published between 1887 and 1893. Conan Doyle killed off Holmes in a final battle with the criminal mastermind Professor James Moriarty in "The Final Problem" (published 1893, but set in 1891), as Conan Doyle felt that "my literary energies should not be directed too much into one channel." However, the reaction of the public surprised Doyle very much. Distressed readers wrote anguished letters to The Strand Magazine, which suffered a terrible blow when 20,000 people cancelled their subscriptions to the magazine in protest. Conan Doyle himself received many protest letters, and one lady even began her letter with "You brute". Legend has it that Londoners were so distraught upon hearing the news of Holmes's death that they wore black armbands in mourning, though there is no known contemporary source for this; the earliest known reference to such events comes from 1949. However, the recorded public reaction to Holmes's death was unlike anything previously seen for fictional events.

After resisting public pressure for eight years, Conan Doyle wrote The Hound of the Baskervilles (serialised in 1901–02, with an implicit setting before Holmes's death). In 1903, Conan Doyle wrote "The Adventure of the Empty House"; set in 1894, Holmes reappears, explaining to a stunned Watson that he had faked his death to fool his enemies. Following "The Adventure of the Empty House", Conan Doyle would sporadically write new Holmes stories until 1927. Holmes aficionados refer to the period from 1891 to 1894—between his disappearance and presumed death in "The Final Problem" and his reappearance in "The Adventure of the Empty House"—as the Great Hiatus. The earliest known use of this expression dates to 1946.

Retirement

In His Last Bow, the reader is told that Holmes has retired to a small farm on the Sussex Downs and taken up beekeeping as his primary occupation. The move is not dated precisely, but can be presumed to be no later than 1904 (since it is referred to retrospectively in "The Adventure of the Second Stain", first published that year). The story features Holmes and Watson coming out of retirement to aid the British war effort. Only one other adventure, "The Adventure of the Lion's Mane", takes place during the detective's retirement.

Personality and habits

Watson describes Holmes as "bohemian" in his habits and lifestyle. Said to have a "cat-like" love of personal cleanliness, at the same time Holmes is an eccentric with no regard for contemporary standards of tidiness or good order. Watson describes him as

in his personal habits one of the most untidy men that ever drove a fellow-lodger to distraction. [He] keeps his cigars in the coal-scuttle, his tobacco in the toe end of a Persian slipper, and his unanswered correspondence transfixed by a jack-knife into the very centre of his wooden mantelpiece. ... He had a horror of destroying documents.... Thus month after month his papers accumulated, until every corner of the room was stacked with bundles of manuscript which were on no account to be burned, and which could not be put away save by their owner.

While Holmes can be dispassionate and cold, during an investigation he is animated and excitable. He has a flair for showmanship, often keeping his methods and evidence hidden until the last possible moment so as to impress observers. His companion condones the detective's willingness to bend the truth (or break the law) on behalf of a client—lying to the police, concealing evidence or breaking into houses—when he feels it morally justifiable.

Except for that of Watson, Holmes avoids casual company. In "The Gloria Scott", he tells the doctor that during two years at college he made only one friend: "I was never a very sociable fellow, Watson ... I never mixed much with the men of my year". The detective goes without food at times of intense intellectual activity, believing that "the faculties become refined when you starve them." At times Holmes relaxes with music, either playing the violin, or enjoying the works of composers such as Wagner and Pablo de Sarasate.

Finances

Holmes is known to charge clients for his expenses and claim any reward offered for a problem's solution, such as in "The Adventure of the Speckled Band", "The Red-Headed League", and "The Adventure of the Beryl Coronet". The detective states at one point that "My professional charges are upon a fixed scale. I do not vary them, save when I remit them altogether". In this context, a client is offering to double his fee, and it is implied that wealthy clients habitually pay Holmes more than his standard rate. In "The Adventure of the Priory School", Holmes earns a £6,000 fee (at a time where annual expenses for a rising young professional were in the area of £500). However, Watson notes that Holmes would refuse to help even the wealthy and powerful if their cases did not interest him.

Attitudes towards women

As Conan Doyle wrote to Joseph Bell, "Holmes is as inhuman as a Babbage's Calculating Machine and just about as likely to fall in love". Holmes says of himself that he is "not a whole-souled admirer of womankind", and that he finds "the motives of women ... inscrutable. ... How can you build on such quicksand? Their most trivial actions may mean volumes..." In The Sign of Four, he says, "Women are never to be entirely trusted—not the best of them", a feeling Watson notes as an "atrocious sentiment". In "The Adventure of the Lion's Mane", Holmes writes, "Women have seldom been an attraction to me, for my brain has always governed my heart". At the end of The Sign of Four, Holmes states that "love is an emotional thing, and whatever is emotional is opposed to that true, cold reason which I place above all things. I should never marry myself, lest I bias my judgement." Ultimately, Holmes claims outright that "I have never loved".

But while Watson says that the detective has an "aversion to women", he also notes Holmes as having "a peculiarly ingratiating way with [them]". Watson notes that their housekeeper Mrs. Hudson is fond of Holmes because of his "remarkable gentleness and courtesy in his dealings with women". .

Irene Adler

Irene Adler is a retired American opera singer and actress who appears in "A Scandal in Bohemia". Although this is her only appearance, she is one of only a handful of people who best Holmes in a battle of wits, and the only woman. For this reason, Adler is the frequent subject of pastiche writing. The beginning of the story describes the high regard in which Holmes holds her:

To Sherlock Holmes she is always the woman. I have seldom heard him mention her under any other name. In his eyes she eclipses and predominates the whole of her sex. It was not that he felt any emotion akin to love for Irene Adler. ... And yet there was but one woman to him, and that woman was the late Irene Adler, of dubious and questionable memory.

Five years before the story's events, Adler had a brief liaison with Crown Prince of Bohemia Wilhelm von Ormstein. As the story opens, the Prince is engaged to another. Fearful that the marriage would be called off if his fiancée's family learns of this past impropriety, Ormstein hires Holmes to regain a photograph of Adler and himself. Adler slips away before Holmes can succeed. Her memory is kept alive by the photograph of Adler that Holmes received for his part in the case.

Knowledge and skills

Shortly after meeting Holmes in the first story, A Study in Scarlet (generally assumed to be 1881, though the exact date is not given), Watson assesses the detective's abilities:

- Knowledge of Literature – nil.

- Knowledge of Philosophy – nil.

- Knowledge of Astronomy – nil.

- Knowledge of Politics – Feeble.

- Knowledge of Botany – Variable. Well up in belladonna and poisons generally. Knows nothing of practical gardening.

- Knowledge of Geology – Practical, but limited. Tells at a glance different soils from each other. After walks, has shown me splashes upon his trousers, and told me by their colour and consistence in what part of London he had received them.

- Knowledge of Chemistry – Profound.

- Knowledge of Anatomy – Accurate, but unsystematic.

- Knowledge of Sensational Literature – Immense. He appears to know every detail of every horror perpetrated in the century.

- Plays the violin well.

- Is an expert singlestick player, boxer, and swordsman.

- Has a good practical knowledge of British law.

In A Study in Scarlet, Holmes claims to be unaware that the earth revolves around the sun since such information is irrelevant to his work; after hearing that fact from Watson, he says he will immediately try to forget it. The detective believes that the mind has a finite capacity for information storage, and learning useless things reduces one's ability to learn useful things. The later stories move away from this notion: in The Valley of Fear, he says, "All knowledge comes useful to the detective", and in "The Adventure of the Lion's Mane", the detective calls himself "an omnivorous reader with a strangely retentive memory for trifles". Looking back on the development of the character in 1912, Conan Doyle wrote that "In the first one, the Study in Scarlet, [Holmes] was a mere calculating machine, but I had to make him more of an educated human being as I went on with him."

Despite Holmes's supposed ignorance of politics, in "A Scandal in Bohemia" he immediately recognises the true identity of the disguised "Count von Kramm". At the end of A Study in Scarlet, Holmes demonstrates a knowledge of Latin. The detective cites Hafez, Goethe, as well as a letter from Gustave Flaubert to George Sand in the original French. In The Hound of the Baskervilles, the detective recognises works by Godfrey Kneller and Joshua Reynolds: "Watson won't allow that I know anything of art, but that is mere jealousy since our views upon the subject differ". In "The Adventure of the Bruce-Partington Plans", Watson says that "Holmes lost himself in a monograph which he had undertaken upon the Polyphonic Motets of Lassus", considered "the last word" on the subject - which must have been the result of an intensive and very specialized musicological study which could have had no possible application to the solution of criminal mysteries.

Holmes is a cryptanalyst, telling Watson that "I am fairly familiar with all forms of secret writing, and am myself the author of a trifling monograph upon the subject, in which I analyse one hundred and sixty separate ciphers". Holmes also demonstrates a knowledge of psychology in "A Scandal in Bohemia", luring Irene Adler into betraying where she hid a photograph based on the premise that a woman will rush to save her most valued possession from a fire. Another example is in "The Adventure of the Blue Carbuncle", where Holmes obtains information from a salesman with a wager: "When you see a man with whiskers of that cut and the 'Pink 'un' protruding out of his pocket, you can always draw him by a bet .... I daresay that if I had put 100 pounds down in front of him, that man would not have given me such complete information as was drawn from him by the idea that he was doing me on a wager".

Maria Konnikova points out in an interview with D. J. Grothe that Holmes practises what is now called mindfulness, concentrating on one thing at a time, and almost never "multitasks". She adds that in this he predates the science showing how helpful this is to the brain.

Holmesian deduction

Holmes observes the dress and attitude of his clients and suspects, noting skin marks (such as tattoos), contamination (such as ink stains or clay on boots), emotional state, and physical condition in order to deduce their origins and recent history. The style and state of wear of a person's clothes and personal items are also commonly relied on; in the stories Holmes is seen applying his method to items such as walking sticks, pipes, and hats. For example, in "A Scandal in Bohemia", Holmes infers that Watson had got wet lately and had "a most clumsy and careless servant girl". When Watson asks how Holmes knows this, the detective answers:

It is simplicity itself ... my eyes tell me that on the inside of your left shoe, just where the firelight strikes it, the leather is scored by six almost parallel cuts. Obviously they have been caused by someone who has very carelessly scraped round the edges of the sole in order to remove crusted mud from it. Hence, you see, my double deduction that you had been out in vile weather, and that you had a particularly malignant boot-slitting specimen of the London slavey.

In the first Holmes story, A Study in Scarlet, Dr. Watson compares Holmes to C. Auguste Dupin, Edgar Allan Poe's fictional detective, who employed a similar methodology. Alluding to an episode in "The Murders in the Rue Morgue", where Dupin determines what his friend is thinking despite their having walked together in silence for a quarter of an hour, Holmes remarks: "That trick of his breaking in on his friend's thoughts with an apropos remark... is really very showy and superficial". Nevertheless, Holmes later performs the same 'trick' on Watson in "The Cardboard Box" and "The Adventure of the Dancing Men".

Though the stories always refer to Holmes's intellectual detection method as "deduction", he primarily relies on abduction: inferring an explanation for observed details. "From a drop of water", he writes, "a logician could infer the possibility of an Atlantic or a Niagara without having seen or heard of one or the other". However, Holmes does employ deductive reasoning as well. The detective's guiding principle, as he says in The Sign of Four, is: "When you have eliminated the impossible, whatever remains, however improbable, must be the truth."

Despite Holmes's remarkable reasoning abilities, Conan Doyle still paints him as fallible in this regard (this being a central theme of "The Yellow Face").

Forensic science

Though Holmes is famed for his reasoning capabilities, his investigative technique relies heavily on the acquisition of hard evidence. Many of the techniques he employs in the stories were at the time in their infancy.

The detective is particularly skilled in the analysis of trace evidence and other physical evidence, including latent prints (such as footprints, hoof prints, and shoe and tire impressions) to identify actions at a crime scene; using tobacco ashes and cigarette butts to identify criminals; handwriting analysis and graphology; comparing typewritten letters to expose a fraud; using gunpowder residue to expose two murderers; and analyzing small pieces of human remains to expose two murders.

Because of the small scale of much of his evidence, the detective often uses a magnifying glass at the scene and an optical microscope at his Baker Street lodgings. He uses analytical chemistry for blood residue analysis and toxicology to detect poisons; Holmes's home chemistry laboratory is mentioned in "The Naval Treaty". Ballistics feature in "The Adventure of the Empty House" when spent bullets are recovered to be matched with a suspected murder weapon, a practice which became regular police procedure only some fifteen years after the story was published.

Laura J. Snyder has examined Holmes's methods in the context of mid- to late-19th-century criminology, demonstrating that, while sometimes in advance of what official investigative departments were formally using at the time, they were based upon existing methods and techniques. For example, fingerprints were proposed to be distinct in Conan Doyle's day, and while Holmes used a thumbprint to solve a crime in "The Adventure of the Norwood Builder" (generally held to be set in 1895), the story was published in 1903, two years after Scotland Yard's fingerprint bureau opened. Though the effect of the Holmes stories on the development of forensic science has thus often been overstated, Holmes inspired future generations of forensic scientists to think scientifically and analytically.

Disguises

Holmes displays a strong aptitude for acting and disguise. In several stories ("The Sign of Four", "The Adventure of Charles Augustus Milverton", "The Man with the Twisted Lip", "The Adventure of the Empty House" and "A Scandal in Bohemia"), to gather evidence undercover he uses disguises so convincing that Watson fails to recognise him. In others ("The Adventure of the Dying Detective" and "A Scandal in Bohemia"), Holmes feigns injury or illness to incriminate the guilty. In the latter story, Watson says, "The stage lost a fine actor ... when [Holmes] became a specialist in crime".

Guy Mankowski has said of Holmes that his ability to change his appearance to blend into any situation "helped him personify the idea of the English eccentric chameleon, in a way that prefigured the likes of David Bowie."

Agents

Until Watson's arrival at Baker Street, Holmes largely worked alone, only occasionally employing agents from the city's underclass. These agents included a variety of informants, such as Langdale Pike, a "human book of reference upon all matters of social scandal", and Shinwell Johnson, who acted as Holmes's "agent in the huge criminal underworld of London". The best known of Holmes's agents are a group of street children he called "the Baker Street Irregulars".

Legacy

The detective story

Although Holmes is not the original fictional detective, his name has become synonymous with the role. Doyle's Sherlock Holmes stories introduced multiple literary devices that have become major conventions in detective fiction, such as the companion character who is not as clever as the detective and has solutions explained to him (thus informing the reader as well), as with Dr. Watson in the Holmes stories. Other conventions introduced by Doyle include the arch-criminal who is too clever for the official police to defeat, like Holmes's adversary Professor Moriarty, and the use of forensic science to solve cases.

The Sherlock Holmes stories established crime fiction as a respectable genre popular with readers of all backgrounds, and Doyle's success inspired many contemporary detective stories. Holmes influenced the creation of other "eccentric gentleman detective" characters, like Agatha Christie's fictional detective Hercule Poirot, introduced in 1920. Holmes also inspired a number of anti-hero characters "almost as an antidote to the masterful detective", such as the gentleman thief characters A. J. Raffles (created by E. W. Hornung in 1898) and Arsène Lupin (created by Maurice Leblanc in 1905).

"Elementary, my dear Watson"

The phrase "Elementary, my dear Watson" has become one of the most quoted and iconic aspects of the character. However, although Holmes often observes that his conclusions are "elementary", and occasionally calls Watson "my dear Watson", the phrase "Elementary, my dear Watson" is never uttered in any of the sixty stories by Conan Doyle. One of the nearest approximations of the phrase appears in "The Adventure of the Crooked Man" (1893) when Holmes explains a deduction: "'Excellent!' I cried. 'Elementary,' said he."

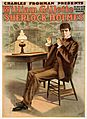

William Gillette is widely considered to have originated the phrase with the formulation, "Oh, this is elementary, my dear fellow", allegedly in his 1899 play Sherlock Holmes. However, the script was revised numerous times over the course of some three decades of revivals and publications, and the phrase is present in some versions of the script, but not others.

The exact phrase, as well as close variants, can be seen in newspaper and journal articles as early as 1909; there is some indication that it was clichéd even then. "Elementary, my dear Watson, elementary" appears in P. G. Wodehouse's novel Psmith, Journalist (serialised 1909–10). The phrase became familiar with the American public in part due to its use in The Rathbone-Bruce series of films from 1939 to 1946.

Museums and special collections

For the 1951 Festival of Britain, Holmes's living room was reconstructed as part of a Sherlock Holmes exhibition, with a collection of original material. After the festival, items were transferred to The Sherlock Holmes (a London pub) and the Conan Doyle collection housed in Lucens, Switzerland by the author's son, Adrian. Both exhibitions, each with a Baker Street sitting-room reconstruction, are open to the public.

In 1969, the Toronto Reference Library began a collection of materials related to Conan Doyle. Stored today in Room 221B, this vast collection is accessible to the public. Similarly, in 1974 the University of Minnesota founded a collection that is now "the world’s largest gathering of material related to Sherlock Holmes and his creator". Access is closed to the general public, but is occasionally open to tours.

In 1990, the Sherlock Holmes Museum opened on Baker Street in London, followed the next year by a museum in Meiringen (near the Reichenbach Falls) dedicated to the detective. A private Conan Doyle collection is a permanent exhibit at the Portsmouth City Museum, where the author lived and worked as a physician.

Works

Novels

- A Study in Scarlet (published November 1887 in Beeton's Christmas Annual)

- The Sign of the Four (published February 1890 in Lippincott's Monthly Magazine)

- The Hound of the Baskervilles (serialised 1901–1902 in The Strand)

- The Valley of Fear (serialised 1914–1915 in The Strand)

Short story collections

The short stories, originally published in magazines, were later collected in five anthologies:

- The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes (stories published 1891–1892 in The Strand)

- The Memoirs of Sherlock Holmes (stories published 1892–1893 in The Strand)

- The Return of Sherlock Holmes (stories published 1903–1904 in The Strand)

- His Last Bow: Some Later Reminiscences of Sherlock Holmes (stories published 1908–1917)

- The Case-Book of Sherlock Holmes (stories published 1921–1927)

See also

In Spanish: Sherlock Holmes para niños

In Spanish: Sherlock Holmes para niños

- List of Holmesian studies

- Popular culture references to Sherlock Holmes

- Sherlock Holmes fandom

Images for kids

-

Waxwork of Robert Downey Jr. as Holmes on display at Madame Tussauds London