Roman aqueduct facts for kids

The Romans constructed aqueducts throughout their Republic and later Empire, to bring water from outside sources into cities and towns. Aqueduct water supplied public baths, latrines, fountains, and private households; it also supported mining operations, milling, farms, and gardens.

Aqueducts moved water through gravity alone, along a slight overall downward gradient within conduits of stone, brick, concrete or lead; the steeper the gradient, the faster the flow. Most conduits were buried beneath the ground and followed the contours of the terrain; obstructing peaks were circumvented or, less often, tunneled through. Where valleys or lowlands intervened, the conduit was carried on bridgework, or its contents fed into high-pressure lead, ceramic, or stone pipes and siphoned across. Most aqueduct systems included sedimentation tanks, which helped to reduce any water-borne debris. Sluices, castella aquae (distribution tanks) and stopcocks regulated the supply to individual destinations, and fresh overflow water could be temporarily stored in cisterns.

Aqueducts and their contents were protected by law and custom. The supply to public fountains took priority over the supply to public baths, and both took priority over supplies to wealthier, fee-paying private users. Some of the wealthiest citizens were given the right to a free supply, as a state honour. In cities and towns, clean run-off water from aqueducts supported high consumption industries such as fulling and dyeing, and industries that employed water but consumed almost none, such as milling. Used water and water surpluses fed ornamental and market gardens, and scoured the drains and public sewers. Unlicensed rural diversion of aqueduct water for agriculture was common during the growing season, but was seldom prosecuted as it helped keep food prices low; agriculture was the core of Rome's economy and wealth.

Rome's first aqueduct was built in 312 BC, and supplied a water fountain at the city's cattle market. By the 3rd century AD, the city had eleven aqueducts, sustaining a population of over a million in a water-extravagant economy; most of the water supplied the city's many public baths. Cities and towns throughout the Roman Empire emulated this model, and funded aqueducts as objects of public interest and civic pride, "an expensive yet necessary luxury to which all could, and did, aspire". Most Roman aqueducts proved reliable and durable; some were maintained into the early modern era, and a few are still partly in use. Methods of aqueduct surveying and construction are noted by Vitruvius in his work De architectura (1st century BC). The general Frontinus gives more detail in his official report on the problems, uses and abuses of Imperial Rome's public water supply. Notable examples of aqueduct architecture include the supporting piers of the Aqueduct of Segovia, and the aqueduct-fed cisterns of Constantinople.

Background

Before the development of aqueduct technology, Romans, like most of their contemporaries in the ancient world, relied on local water sources such as springs and streams, supplemented by groundwater from privately or publicly owned wells, and by seasonal rain-water drained from rooftops into storage jars and cisterns. Such localised sources for fresh water – especially wells – were intensively exploited by the Romans throughout their history, but reliance on the water resources of a small catchment area restricted the city's potential for growth and security. The water of the River Tiber was close at hand, but would have been polluted by water-borne disease. Rome's aqueducts were not strictly Roman inventions – their engineers would have been familiar with the water-management technologies of Rome's Etruscan and Greek allies – but they proved conspicuously successful. By the early Imperial era, the city's aqueducts helped support a population of over a million, and an extravagant water supply for public amenities had become a fundamental part of Roman life.

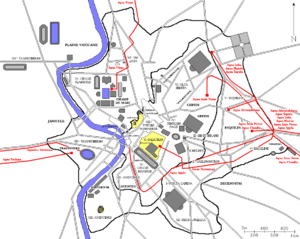

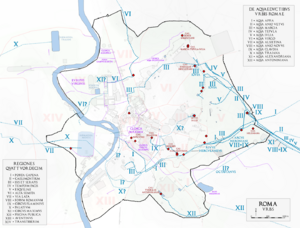

Rome's aqueducts

The city's aqueducts and their dates of completion were:

- 312 BC Aqua Appia

- 272 BC Aqua Anio Vetus

- 144–140 BC Aqua Marcia

- 127–126 BC Aqua Tepula

- 33 BC Aqua Julia

- 19 BC Aqua Virgo

- 2 BC Aqua Alsietina

- 38–52 AD Aqua Claudia

- 38–52 AD Aqua Anio Novus

- 109 AD Aqua Traiana

- 226 AD Aqua Alexandrina

The city's demand for water had probably long exceeded its local supplies by 312 BC, when the city's first aqueduct, the Aqua Appia, was commissioned by the censor Appius Claudius Caecus. The Aqua Appia was one of two major public projects of the time; the other was a military road between Rome and Capua, the first leg of the so-called Appian Way. Both projects had significant strategic value, as the Third Samnite War had been under way for some thirty years by that point. The road allowed rapid troop movements; and by design or fortunate coincidence, most of the Aqua Appia ran within a buried conduit, relatively secure from attack. It was fed by a spring 16.4 km from Rome, and dropped 10 m over its length to discharge approximately 75,500 m3 of water each day into a fountain at Rome's cattle market, the Forum Boarium, one of the city's lowest-lying public spaces.

A second aqueduct, the Aqua Anio Vetus, was commissioned some forty years later, funded by treasures seized from Pyrrhus of Epirus. Its flow was more than twice that of the Aqua Appia, and supplied water to higher elevations of the city.

By 145 BC, the city had again outgrown its combined supplies. An official commission found the aqueduct conduits decayed, their water depleted by leakage and illegal tapping. The praetor Quintus Marcius Rex restored them, and introduced a third, "more wholesome" supply, the Aqua Marcia, Rome's longest aqueduct and high enough to supply the Capitoline Hill. As demand grew still further, more aqueducts were built, including the Aqua Tepula in 127 BC and the Aqua Julia in 33 BC.

Aqueduct building programmes in the city reached a peak in the Imperial Era; political credit and responsibility for provision of public water supplies passed from mutually competitive Republican political magnates to the emperors. Augustus' reign saw the building of the Aqua Virgo, and the short Aqua Alsietina. The latter supplied Trastevere with large quantities of non-potable water for its gardens and was used to create an artificial lake for staged sea-fights to entertain the populace. Another short Augustan aqueduct supplemented the Aqua Marcia with water of "excellent quality". The emperor Caligula added or began two aqueducts completed by his successor Claudius; the 69 km (42.8 mile) Aqua Claudia, which gave good quality water but failed on several occasions; and the Anio Novus, highest of all Rome's aqueducts and one of the most reliable but prone to muddy, discoloured waters, particularly after rain, despite its use of settling tanks.

Most of Rome's aqueducts drew on various springs in the valley and highlands of the Anio, the modern river Aniene, east of the Tiber. A complex system of aqueduct junctions, tributary feeds and distribution tanks supplied every part of the city. Trastevere, the city region west of the Tiber, was primarily served by extensions of several of the city's eastern aqueducts, carried across the river by lead pipes buried in the roadbed of the river bridges, thus forming an inverted siphon. Whenever this cross-river supply had to be shut down for routine repair and maintenance works, the "positively unwholesome" waters of the Aqua Alsietina were used to supply Trastevere's public fountains. The situation was finally ameliorated when the emperor Trajan built the Aqua Traiana in 109 AD, bringing clean water directly to Trastavere from aquifers around Lake Bracciano.

By the late 3rd century AD, the city was supplied with water by eleven state-funded aqueducts. Their combined conduit length is estimated between 780 and a little over 800 km, of which approximately 47 km (29 mi) were carried above ground level, on masonry supports. Most of Rome's water was carried by four of these: the Aqua Anio Vetus, the Aqua Marcia, the Aqua Claudia and the Aqua Anio Novus. Modern estimates of the city's supply, based on Frontinus' own calculations in the late 1st century, range from a high of 1,000,000 m3 per day to a more conservative 520,000–635,000 m3 per day, supplying an estimated population of 1,000,000.

Aqueducts in the Roman Empire

Hundreds of aqueducts were built throughout the Roman Empire. Many of them have since collapsed or been destroyed, but a number of intact portions remain. The Zaghouan Aqueduct, 92.5 km (57.5 mi) in length, was built in the 2nd century AD to supply Carthage (in modern Tunisia). Surviving provincial aqueduct bridges include the Pont du Gard in France and the Aqueduct of Segovia in Spain. The longest single conduit, at over 240 km, is associated with the Valens Aqueduct of Constantinople. "The known system is at least two and half times the length of the longest recorded Roman aqueducts at Carthage and Cologne, but perhaps more significantly it represents one of the most outstanding surveying achievements of any pre-industrial society". Rivalling this in terms of length and possibly equaling or exceeding it in cost and complexity, is provincial Italy's Aqua Augusta. It supplied a great number of luxury coastal holiday-villas belonging to Rome's rich and powerful, several commercial fresh-water fisheries, market-gardens, vineyards and at least eight cities, including the major ports at Naples and Misenum; sea voyages by traders and Rome's Republican and Imperial navies required copious on-board supplies of fresh water.

Aqueducts were built to supply Roman military bases in Britain. The sites of permanent fortresses show traces of fountains and piped water, which were probably supplied by aqueducts from the Claudian period on. Permanent auxiliary forts were supplied by aqueducts from the Flavian period, possibly co-incident with the regular demand for dependable water supplies by provincial military settlements equipped with bathhouses, once these were introduced.

Planning, surveying and management

Planning

The plans for any public or private aqueduct had to be submitted to scrutiny by civil authorities. Permission was granted only if the proposal respected the water rights of other citizens. Inevitably, there would have been rancorous and interminable court cases between neighbours or local governments over competing claims to limited water supplies but on the whole, Roman communities took care to allocate shared water resources according to need. Planners preferred to build public aqueducts on public land (ager publicus), and to follow the shortest, unopposed, most economical route from source to destination. State purchase of privately owned land, or re-routing of planned courses to circumvent resistant or tenanted occupation, could significantly add to the aqueduct's eventual length, and thus to its cost.

On rural land, a protective "clear corridor" was marked out with boundary slabs (cippi) usually 15 feet each side of the channel, reducing to 5 feet each side for lead pipes and in built-up areas. The conduits, their foundations and superstructures, were property of the State or emperor. The corridors were public land, with public rights of way and clear access to the conduits for maintenance. Within the corridors, potential sources of damage to the conduits were forbidden, including new roadways that crossed over the conduit, new buildings, ploughing or planting, and living trees, unless entirely contained by a building. The harvesting of hay and grass for fodder was permitted. Regulations and restrictions necessary to the aqueduct's long-term integrity and maintenance were not always readily accepted or easily enforced at a local level, particularly when ager publicus was understood to be common property, to be used for whatever purpose seemed fit to its user.

After ager publicus, minor, local roads and boundaries between adjacent private properties offered the least costly routes, though not always the most straightforward. Sometimes the State would purchase the whole of a property, mark out the intended course of the aqueduct, and resell the unused land to help mitigate the cost. Graves and cemeteries, temples, shrines and other sacred places had to be respected; they were protected by law, and villa and farm cemeteries were often deliberately sited very close to public roadways and boundaries. Despite careful enquiries by planners, problems regarding shared ownership or uncertain legal status might emerge only during the physical construction. While surveyors could claim ancient right to use land once public, now private, for the good of the State, the land's current possessors could take out a legal counterclaim for compensation based on their long usage, productivity and improvements. They could also join forces with their neighbours to present a united legal front in seeking higher rates of compensation. Aqueduct planning "traversed a legal landscape at least as daunting as the physical one".

In the aftermath of the Second Punic War, the censors exploited a legal process known as vindicatio, a repossession of private or tenanted land by the state, "restoring" it to a presumed ancient status as "public and sacred, and open to the people". Livy describes this as a public-spirited act of piety, and makes no reference to the likely legal conflicts arising. In 179 BC the censors used the same legal device to help justify public contracts for several important building projects, including Rome's first stone-built bridge over the Tiber and a new aqueduct to supplement the city's existing – but, by now, inadequate – supply. A wealthy landowner along the aqueduct's planned route, M. Licinius Crassus, refused it passage across his fields, and seems to have forced its abandonment.

The construction of Rome's third aqueduct, the Aqua Marcia, was at first legally blocked on religious grounds, under advice from the decemviri (an advisory "board of ten"). The new aqueduct was meant to supply water to the highest elevations of the city, including the Capitoline Hill, but the decemviri had consulted Rome's main written oracle, the Sibylline Books, and found there a warning against supplying water to the Capitoline. This brought the project to a standstill. Eventually, having raised the same objections in 143 and in 140, the decemviri and Senate consented, and 180,000,000 sesterces were allocated for restoration of the two existing aqueducts and completion of the third, in 144–140. The Marcia was named for the praetor Quintus Marcius Rex, who had championed its construction.

Sources and surveying

Springs were by far the most common sources for aqueduct water; most of Rome's supply came from various springs in the Anio valley and its uplands. Spring water was fed into a stone or concrete springhouse, then entered the aqueduct conduit. Scattered springs would require several branch conduits feeding into a main channel. Some systems drew water from open, purpose-built, dammed reservoirs, such as the two (still in use) that supplied the aqueduct at the provincial city of Emerita Augusta.

The territory over which the aqueduct ran had to be carefully surveyed to ensure the water would flow at a consistent and acceptable rate for the entire distance. Roman engineers used various surveying tools to plot the course of aqueducts across the landscape. They checked horizontal levels with a chorobates, a flatbedded wooden frame some 20 feet long, fitted with both a water level and plumblines. Horizontal courses and angles could be plotted using a groma, a relatively simple apparatus that was eventually displaced by the more sophisticated dioptra, a precursor of the modern theodolite. In Book 8 of his De architectura, Vitruvius describes the need to ensure a constant supply, methods of prospecting, and tests for potable water.

Water and health

Greek and Roman physicians were well aware of the association between stagnant or tainted waters and water-borne diseases, and held rainwater to be water's purest and healthiest form, followed by springs. Rome's public baths, ostensibly one of Rome's greatest contributions to the health of its inhabitants, were also instrumental in the spread of waterborne diseases. In his De Medicina, the encyclopaedist Celsus warned that public bathing could induce gangrene in unhealed wounds. Frontinus preferred a high rate of overflow in the aqueduct system because it led to greater cleanliness in the water supply, the sewers, and those who used them.

The adverse health effects of lead on those who mined and processed it were also well known. Ceramic pipes, unlike lead, left no taint in the water they carried, and were therefore preferred over lead for drinking water. In some parts of the Roman world, particularly in relatively isolated communities with localised water systems and limited availability of other, more costly materials, wooden pipes were commonly used; Pliny recommends water-pipes of pine and alder as particularly durable, when kept wet and buried. Examples revealed through archaeology include pipes of alder, clamped at their joints with oak, at Vindolanda fort and pipes of alder in Germany. Where lead pipes were used, a continuous water-flow and the inevitable deposition of water-borne minerals within the pipes somewhat reduced the water's contamination by soluble lead. Lead content in Rome's aqueduct water was "clearly measurable, but unlikely to have been truly harmful". Nevertheless, the level of lead was 100 times higher than in local spring waters.

Conduits and gradients

Most Roman aqueducts were flat-bottomed, arch-section conduits, approximately 0.7 m (2.3 ft) wide and 1.5 m (5 ft) high internally, running 0.5 to 1 m beneath the ground surface, with inspection-and-access covers at regular intervals. Conduits above ground level were usually slab-topped. Early conduits were ashlar-built but from around the late Republican era, brick-faced concrete was often used instead. The concrete used for conduit linings was usually waterproof, with a very smooth finish. The flow of water depended on gravity alone. The volume of water transported within the conduit depended on the catchment hydrology – rainfall, absorption, and runoff – the cross section of the conduit, and its gradient; most conduits ran about two-thirds full. The conduit's cross section was also determined by maintenance requirements; workmen must be able to enter and access the whole, with minimal disruption to its fabric.

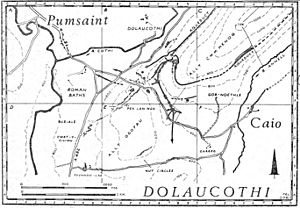

Vitruvius recommends a low gradient of not less than 1 in 4800 for the channel, presumably to prevent damage to the structure through erosion and water pressure. This value agrees well with the measured gradients of surviving masonry aqueducts. The gradient of the Pont du Gard is only 34 cm per km, descending only 17 m vertically in its entire length of 50 km (31 mi): it could transport up to 20,000 cubic metres a day. The gradients of temporary aqueducts used for hydraulic mining could be considerably greater, as at Dolaucothi in Wales (with a maximum gradient of about 1:700) and Las Medulas in northern Spain. Where sharp gradients were unavoidable in permanent conduits, the channel could be stepped downwards, widened or discharged into a receiving tank to disperse the flow of water and reduce its abrasive force. The use of stepped cascades and drops also helped re-oxygenate and thus "freshen" the water.

Bridgework, siphons and tunnels

Some aqueduct conduits were supported across valleys or hollows on multiple piered arches of masonry, brick or concrete, also known as arcades. The Pont du Gard, one of the most impressive surviving examples of a massive masonry multiple-piered conduit, spanned the Gardon river-valley some 48.8 m (160 ft) above the Gardon itself. Where particularly deep or lengthy depressions had to be crossed, inverted siphons could be used, instead of arcades; the conduit fed water into a header tank, which fed it into pipes. The pipes crossed the valley at lower level, supported by a low "venter" bridge, then rose to a receiving tank at a slightly lower elevation. This discharged into another conduit; the overall gradient was maintained. Siphon pipes were usually made of soldered lead, sometimes reinforced by concrete encasements or stone sleeves. Less often, the pipes were stone or ceramic, jointed as male-female and sealed with lead.

Vitruvius describes the construction of siphons and the problems of blockage, blow-outs and venting at their lowest levels, where the pressures were greatest. Nonetheless, siphons were versatile and effective if well-built and well-maintained. A horizontal section of high-pressure siphon tubing in the Aqueduct of the Gier was ramped up on bridgework to clear a navigable river, using nine lead pipes in parallel, cased in concrete. Modern hydraulic engineers use similar techniques to enable sewers and water pipes to cross depressions. At Romano-Gallic Arles, a minor branch of the main aqueduct supplied a local suburb via a lead siphon whose "belly" was laid across a riverbed, eliminating any need for supporting bridgework.

Some aqueducts running through hilly regions employed a combination of arcades, plain conduits buried at ground level, and tunnels large enough to contain the conduit, its builders and maintenance workers. The builders of Campana's Aqua Augusta changed the water's orientation from an existing northerly watershed to a southerly watershed, establishing the new gradient using a 6 km tunnel, several shorter tunnels, and arcades, one of which was supported more or less at sea level by foundations on the sea bed at Misenum. En route, it supplied several cities and many villas, using branch lines.

Inspection and maintenance

Roman aqueducts required a comprehensive system of regular maintenance. On the standard, buried conduits, inspection and access points were provided at regular intervals, so that suspected blockages or leaks could be investigated with minimal disruption of the supply. Water lost through multiple, slight leaks in buried conduit walls could be hard to detect except by its fresh taste, unlike that of the natural groundwater. The clear corridors created to protect the fabric of underground and overground conduits were regularly patrolled for unlawful ploughing, planting, roadways and buildings. In De aquaeductu, Frontinus describes the penetration of conduits by tree-roots as particularly damaging.

Working patrols would have cleared algal fouling, repaired accidental breaches or accessible shoddy workmanship, cleared the conduits of gravel and other loose debris, and removed accretions of calcium carbonate (also known as travertine) in systems fed by hard water sources; modern research has found that quite apart from the narrowing of apertures, even slight roughening of the aqueduct's ideally smooth-mortared interior surface by travertine deposits could significantly reduce the water's velocity, and thus its rate of flow, by up to 1/4. Accretions within siphons could drastically reduce flow rates through their already narrow diameters, though some had sealed openings that might have been used as rodding eyes, possibly using a pull-through device. In Rome, where a hard-water supply was the norm, mains pipework was shallowly buried beneath road kerbs, for ease of access; the accumulation of calcium carbonate in these pipes would have necessitated their frequent replacement.

Full closure of any aqueduct for servicing would have been a rare event, kept as brief as possible, with repair shut-downs preferably made when water demand was lowest, during the winter months. The piped water supply could be selectively reduced or shut off at the castella when small or local repairs were needed, but substantial maintenance and repairs to the aqueduct conduit itself required the complete diversion of water at any point upstream, including the spring-head itself. Frontinus describes the use of temporary leaden conduits to carry the water past damaged stretches while repairs were made, with minimal loss of supply.

The Aqua Claudia, most ambitious of the City of Rome's aqueducts, suffered at least two serious partial collapses over two centuries, one of them very soon after construction, and both probably due to a combination of shoddy workmanship, underinvestment, Imperial negligence, collateral damage through illicit outlets, natural ground tremors and damage by overwhelming seasonal floods originating upstream. Inscriptions claim that it was largely out of commission, and awaiting repair, for nine years prior to a restoration by Vespasian and another, later, by his son Titus. To many modern scholars, the delay seems implausibly long. It might well have been thought politic to stress the personal generosity of the new Flavian dynasty, father and son, and exaggerate the negligence of their disgraced imperial predecessor, Nero, whose rebuilding priorities after Rome's Great Fire were thought models of self-indulgent ambition.

Distribution

Aqueduct mains could be directly tapped, but they more usually fed into public distribution terminals, known as castellum aquae ("water castles"), which acted as settling tanks and cisterns and supplied various branches and spurs, via lead or ceramic pipes. These pipes were made in 25 different standardised diameters and were fitted with bronze stopcocks. The flow from each pipe (calix) could be fully or partly opened, or shut down, and its supply diverted if necessary to any other part of the system in which water-demand was, for the time being, outstripping supply. The free supply of water to public basins and drinking fountains was officially prioritised over the supply to the public baths, where a very small fee was charged to every bather, on behalf of the Roman people. The supply to basins and baths was in turn prioritised over the requirements of fee-paying private users. The last were registered, along with the bore of pipe that led from the public water supply to their property – the wider the pipe, the greater the flow and the higher the fee. Some properties could be bought and sold with a legal right to draw water attached. Aqueduct officials could assign the right to draw overflow water (aqua caduca, literally "fallen water") to certain persons and groups; fullers, for example, used a great deal of fresh water in their trade, in return for a commensurate water-fee. Some individuals were gifted a right to draw overflow water gratis, as a State honour or grant; pipe stamps show that around half Rome's water grants were given to elite, extremely wealthy citizens of the senatorial class. Water grants were issued by the emperor or State to named individuals, and could not be lawfully sold along with a property, or inherited: new owners and heirs must therefore negotiate a new grant, in their own name. In the event, these untransferable, personal water grants were more often transferred than not.

Frontinus thought dishonest private users and corrupt state employees were responsible for most of the losses and outright thefts of water in Rome, and the worst damage to the aqueducts. His De aquaeductu can be read as a useful technical manual, a display of persuasive literary skills, and a warning to users and his own staff that if they stole water, they would be found out, because he had all the relevant, expert calculations to hand. He claimed to know not only how much was stolen, but how it was done. Tampering and fraud were indeed commonplace; methods included the fitting of unlicensed or additional outlets, some of them many miles outside the city, and the illegal widening of lead pipes. Any of this might involve the bribery or connivance of unscrupulous aqueduct officials or workers. Archaeological evidence confirms that some users drew an illegal supply but not the likely quantity involved, nor the likely combined effect on supply to the city as a whole. The measurement of allowances was basically flawed; officially approved lead pipes carried inscriptions with information on the pipe's manufacturer, its fitter, and probably on its subscriber and their entitlement; but water allowance was measured in quinaria (cross-sectional area of the pipe) at the point of supply and no formula or physical device was employed to account for variations in velocity, rate of flow or actual usage. Brun, 1991, used lead pipe stamps to calculate a plausible water distribution as a percentage of the whole; 17% went to the emperor (including his gifts, grants and awards); 38% went to private individuals; and 45% went to the public at large, including public baths and fountains.

Management

In the Republican era, aqueducts were planned, built and managed under authority of the censors, or if no censor was in office, the aediles. In the Imperial era, lifetime responsibility for water supplies passed to the emperors. Rome had no permanent central body to manage the aqueducts until Augustus created the office of water commissioner (curator aquarum); this was a high status, high-profile Imperial appointment. In 97 AD, Frontinus, who had already had a distinguished career as consul, general and provincial governor, served both as consul and as curator aquarum, under the emperor Nerva.

Particular sections of Campania's very long, complex, costly and politically sensitive Aqua Augusta, constructed in the early days of the Augustan principate were supervised by wealthy, influential, local curatores. They were drawn from local elites by the local electorate, or by Augustus himself. The entire network relied on just two mountain springs, shared with a river that supported freshwater fish, providing a free food source for all classes. The Augusta supplied eight or nine municipalities or cities and an unknown number of farms and villas, including bathhouses, via branch lines and sub-branch lines; its extremities were the naval port of Misenum and the merchant port of Puteoli. Its delivery is unlikely to have been wholly reliable, adequate or free from dispute. Competition would have been inevitable.

Under the emperor Claudius, the City of Rome's contingent of imperial aquarii (aqueduct workers) comprised a familia aquarum of 460, both slave and free, funded through a combination of Imperial largesse and the water fees paid by private subscribers. The familia aquarum comprised "overseers, reservoir‐keepers, line‐walkers, pavers, plasterers, and other workmen" supervised by an Imperial freedman, who held office as procurator aquarium. The curator aquarum had magisterial powers in relation to the water supply, assisted by a team of architects, public servants, notaries and scribes, and heralds; when working outside the city, he was further entitled to two lictors to enforce his authority. Substantial fines could be imposed for even single offences against the laws relating to aqueducts: for example, 10,000 sesterces for allowing a tree to damage the conduit, and 100,000 sesterces for polluting the water within the conduit, or allowing one's slave to do the same.

Uses

Civic and domestic

Rome's first aqueduct (312 BC) discharged at very low pressure and at a more-or-less constant rate in the city's main trading centre and cattle-market, probably into a low-level, cascaded series of troughs or basins; the upper for household use, the lower for watering the livestock traded there. Most Romans would have filled buckets and storage jars at the basins and carried the water to their apartments; the better-off would have sent slaves to perform the same task. The outlet's elevation was too low to offer any city household or building a direct supply; the overflow drained into Rome's main sewer, and from there into the Tiber. Most inhabitants still relied on well water and rainwater. At this time, Rome had no public baths. The first was probably built in the next century, based on precursors in neighbouring Campania; a limited number of private baths and small, street-corner public baths would have had a private water supply, but once aqueduct water was brought to the city's higher elevations, large and well-appointed public baths and fountains were built throughout the city. Public baths and fountains became distinctive features of Roman civilization, and the baths, in particular, became important social centres.

The majority of urban Romans lived in multi-storeyed blocks of flats (insulae). Some blocks offered water services, but only to tenants on the more expensive, lower floors; the other tenants would have drawn their water gratis from public fountains. During the Imperial era, lead production (mostly for pipes) became an Imperial monopoly, and the granting of rights to draw water for private use from state-funded aqueducts was made an imperial privilege. The provision of free, potable water to the general public became one among many gifts to the people of Rome from their emperor, paid for by him or by the state. In 33 BC, Marcus Agrippa built or subsidised 170 public bath-houses during his aedileship. In Frontinus's time (c. 40–103 AD), around 10% of Rome's aqueduct water was used to supply 591 public fountains, among which were 39 lavishly decorative fountains that Frontinus calls munera. According to one of several much later regionaries, by the end of the 4th century AD, Rome's aqueducts within the City – 19 of them, according to the regionary – fed 11 large public baths, 965 smaller public bathhouses and 1,352 public fountains.

Farming

Between 65 and 90% of the Roman Empire's population was involved in some form of agricultural work. Water was possibly the most important variable in the agricultural economy of the Mediterranean world. Roman Italy's natural fresh-water sources – springs, streams, rivers and lakes – were abundant in some places, entirely absent in others. Rainfall was unpredictable. Water tended to be scarce when most needed during the warm, dry summer growing season. Farmers whose villas or estates were near a public aqueduct could draw, under license, a specified quantity of aqueduct water for irrigation at a predetermined time, using a bucket let into the conduit via the inspection hatches; this was intended to limit the depletion of water supply to users further down the gradient, and help ensure a fair distribution among competitors at the time when water was most needed and scarce. Columella recommends that any farm should contain a "never failing" spring, stream or river; but acknowledges that not every farm did.

Farmland without a reliable summer water-source was virtually worthless. During the growing season, a "modest local" irrigation system might consume as much water as the city of Rome; and the livestock whose manure fertilised the fields must be fed and watered all year round. At least some Roman landowners and farmers relied in part or whole on aqueduct water to raise crops as their primary or sole source of income but the fraction of aqueduct water involved can only be guessed at. More certainly, the creation of municipal and city aqueducts brought a growth in the intensive and efficient suburban market-farming of fragile, perishable commodities such as flowers (for perfumes, and for festival garlands), grapes, vegetables and orchard fruits; and of small livestock such as pigs and chickens, close to the municipal and urban markets.

A licensed right to use aqueduct water on farmland could lead to increased productivity, a cash income through the sale of surplus foodstuffs, and an increase in the value of the land itself. In the countryside, permissions to draw aqueduct water for irrigation were particularly hard to get; the exercise and abuse of such rights were subject to various known legal disputes and judgements, and at least one political campaign; in 184 BC Cato tried to block all unlawful rural outlets, especially those owned by the landed elite. This may be connected to Cato's diatribe as censor against the ex-consul Lucius Furius Purpureo: "Look how much he bought the land for, where he is channeling the water!" Cato's attempted reform proved impermanent at best. Though illegal tapping could be punished by seizure of assets, including the illegally watered land and its produce, this law seems never to have been used, and was probably impracticable; while water thefts profited farmers, they could also create food surpluses and keep food prices low. Grain shortages in particular could lead to famine and social unrest. Any practical solution must strike a balance between the water-needs of urban populations and grain producers, tax the latter's profits, and secure sufficient grain at reasonable cost for the Roman poor (the so-called "corn dole") and the army. Rather than seek to impose unproductive and probably unenforcable bans, the authorities issued individual water grants and licenses, and regulated water outlets though with variable success. In the 1st century AD, Pliny the Elder, like Cato, could fulminate against grain producers who continued to wax fat on profits from public water and public land.

Some landholders avoided such restrictions and entanglements by buying water access rights to distant springs, not necessarily on their own land. A few, of high wealth and status, built their own aqueducts to transport such water from source to field or villa; Mumius Niger Valerius Vegetus bought the rights to a spring and its water from his neighbour, and access rights to a corridor of intervening land, then built an aqueduct of just under 10 kilometres, connecting the springhead to his own villa.

Industrial

Some aqueducts supplied water to industrial sites, usually via an open channel cut into the ground, clay-lined or wood-shuttered to reduce water loss. Most such leats were designed to operate at the steep gradients that could deliver the high water volumes needed in mining operations. Water was used in hydraulic mining to strip the overburden and expose the ore by hushing, to fracture and wash away metal-bearing rock already heated and weakened by fire-setting, and to power water-wheel driven stamps and trip-hammers that crushed ore for processing. Evidence of such leats and machines has been found at Dolaucothi in south-west Wales.

Mining sites, such as Dolaucothi and Las Medulas in north-west Spain, show multiple aqueducts that fed water from local rivers to the mine head. The channels may have deteriorated rapidly, or become redundant as the nearby ore was exhausted. Las Medulas shows at least seven such leats, and Dolaucothi at least five. At Dolaucothi, the miners used holding reservoirs, as well as hushing tanks and sluice gates to control flow, and drop chutes were used for the diversion of water supplies. The remaining traces (see palimpsest) of such channels allows the mining sequence to be inferred.

A number of other sites fed by several aqueducts have not yet been thoroughly explored or excavated, such as those at Longovicium near Lanchester, south of Hadrian's wall, in which the water supplies may have been used to power trip-hammers for forging iron.

At Barbegal in Roman Gaul, a reservoir fed an aqueduct that drove a cascaded series of 15 or 16 overshot water mills, grinding flour for the Arles region. Similar arrangements, though on a lesser scale, have been found in Caesarea, Venafrum and Roman-era Athens. Rome's Aqua Traiana drove a flour-mill at the Janiculum, west of the Tiber. A mill in the basement of the Baths of Caracalla was driven by aqueduct overspill; this was one of many city mills driven by aqueduct water, with or without official permission. A law of the 5th century forbade the illicit use of aqueduct water for milling.

Decline in use

During the fall of the Western Roman Empire, some aqueducts were deliberately cut by enemies. In 537, the Ostrogoths laid siege to Rome, and cut the aqueduct supply to the city, including the aqueduct-driven grist-mills of the Janiculum. Belisarius, defender of the city, had mills stationed on the Tiber instead, and blocked the conduits to prevent their use by the Ostrogoths as ways through the city defences. In time, some of the city's damaged aqueducts were partly restored, but the city's population was much reduced and impoverished. Most of the aqueducts gradually decayed for want of maintenance, creating swamps and marshes at their broken junctions. By the late medieval period, only the Aqua Virgo still gave a reliable supply to supplement Rome's general dependence on wells and rainwater cisterns. In the provinces, most aqueducts fell into disuse because of deteriorating Roman infrastructure and lack of maintenance, such as the Eifel aqueduct (pictured right). Observations made by the Spaniard Pedro Tafur, who visited Rome in 1436, reveal misunderstandings of the very nature of the Roman aqueducts:

Through the middle of the city runs a river, which the Romans brought there with great labour and set in their midst, and this is the Tiber. They made a new bed for the river, so it is said, of lead, and channels at one and the other end of the city for its entrances and exits, both for watering horses and for other services convenient to the people, and anyone entering it at any other spot would be drowned.

During the Renaissance, the standing remains of the city's massive masonry aqueducts inspired architects, engineers and their patrons; Pope Nicholas V renovated the main channels of the Roman Aqua Virgo in 1453. Many aqueducts in Rome's former empire were kept in good repair. The 15th-century rebuilding of an aqueduct at Segovia in Spain shows advances on the Pont du Gard by using fewer arches of greater height, and so greater economy in its use of the raw materials. The skill in building aqueducts was not lost, especially of the smaller, more modest channels used to supply water wheels. Most such mills in Britain were developed in the medieval period for bread production, and used similar methods as that developed by the Romans with leats tapping local rivers and streams.

See also

- List of Roman aqueduct bridges

- Roman architectural revolution

- Ancient Roman architecture

- Ancient Roman engineering

- Ancient Roman technology

- Roman concrete