Rembert Dodoens facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Rembert Dodoens

|

|

|---|---|

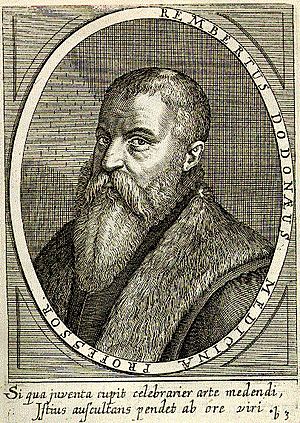

Engraving by Theodor de Bry, in Bibliotheca chalcographica (1669)

|

|

| Born |

Rembert Van Joenckema

29 June 1517 Mechelen, Flanders (now Belgium)

|

| Died | 10 March 1585 (aged 67) Leiden, South Holland, The Netherlands

|

| Resting place | Pieterskerk, Leiden |

| Nationality | Flemish |

| Other names | Rembertus Dodonaeus |

| Alma mater | University of Leuven |

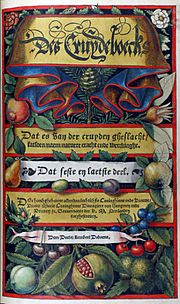

| Known for | Cruydboeck, a "Herbal" |

| Spouse(s) |

|

| Children | 5 |

| Parent(s) | Denis van Joenckema and Ursula Roelants |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Medicine, botany |

| Institutions | Mechelin, Vienna, Leiden University |

| Influences | Otto Brunfels, Jerome Bock, Leonhard Fuchs |

| Author abbrev. (botany) | Dodoens |

Rembert Dodoens (born Rembert Van Joenckema, 29 June 1517 – 10 March 1585) was a Flemish physician and botanist, also known under his Latinized name Rembertus Dodonaeus. He has been called the father of botany.

Life

Dodoens was born Rembert van Joenckema in Mechelen, then the capital of the Spanish Netherlands in 1517. His parents were Denis van Joenckema (d. 1533) and Ursula Roelants. The van Joenckema family and name are Frisian in origin. Its members were active in politics and jurisprudence in Friesland and some had moved in 1516 to Mechelen. His father was one of the municipal physicians in Mechelen and a private physician to Margaret of Austria, Governor of the Netherlands, in her final illness. Margaret of Austria's court was based in Mechelen. Rembert later changed his last name to Dodoens (literally "Son of Dodo", a form of his father's name, Denis or Doede).

He was educated at the municipal college in Mechelen before beginning his studies in medicine, cosmography and geography at the age of 13 at the University of Leuven (Louvain), under Arnold Noot, Leonard Willemaer, Jean Heems, and Paul Roelswhere. He graduated with a licentiate in medicine in 1535, and as was the custom of the time, began extensive travels (Wanderjahren) in Europe till 1546, including Italy, Germany, and France. In 1539 he married Kathelijne De Bruyn (1517–1572), who came from a medical family in Mechelen. With her he had four children, Ursula (b. 1544), Denijs (b. 1548), Antonia and Rembert Dodoens. He had a short stay in Basel (1542–1546). In 1557, Dodoens turned down a chair at the University of Leuven. He also turned down an offer to become court physician of king Philip II of Spain. After his wife's death at the age of 55 in 1572, he married Maria Saerinen by whom he had a daughter, Johanna. He died in Leiden in 1585, and was buried at Pieterskerk, Leiden.

After graduation, he followed in his father's footsteps by becoming in 1548 one of the three municipal physicians in Mechelen together with Joachim Roelandts and Jacob De Moor. He was the court physician of the Holy Roman emperor Maximilian II, and his successor, Austrian emperor Rudolph II in Vienna (1575–1578). In 1582, he was appointed professor in medicine at the University of Leiden.

State of botanical science in Dodoens' time

In the early sixteenth century the general belief was that the plant world had been completely described by Dioscorides in his De Materia Medica. During Dodoens' lifetime, botanical knowledge was undergoing enormous expansion, partly fueled by the expansion of the known plant world by New World exploration, the discovery of printing and the use of wood-block illustration. This period is thought of as a botanical Renaissance. Europe became fascinated with natural history from the 1530s, and gardening and cultivation of plants became a passion and prestigious pursuit from monarchs to universities. The first botanical gardens appeared as well as the first illustrated botanical encyclopaedias, together with thousands of watercolours and woodcuts. The experience of farmers, gardeners, foresters, apothecaries and physicians was being supplemented by the rise of the plant expert. Collecting became a discipline, specifically the Kunst- und Wunderkammern (cabinets of curiosities) outside of Italy and the study of naturalia became widespread through many social strata. The great botanists of the sixteenth century were all, like Dodoens, originally trained as physicians, who pursued a knowledge of plants not just for medicinal properties, but in their own right. Chairs in botany, within medical faculties were being established in European universities throughout the sixteenth century in reaction to this trend, and the scientific approach of observation, documentation and experimentation was being applied to the study of plants.

Otto Brunfels published his Herbarium in 1530, followed by those of Jerome Bock (1539) and Leonhard Fuchs (1542), men that Kurt Sprengel would later call the “German fathers of botany”. These men all influenced Dodoens, who was their successor.

See also

In Spanish: Rembert Dodoens para niños

In Spanish: Rembert Dodoens para niños