Rashi facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Rashi

רש״י |

|

|---|---|

16th-century depiction of Rashi

|

|

| Born | February 22, 1040 Troyes, County of Champagne, France

|

| Died | July 13, 1105 (aged 65) Troyes, County of Champagne, France

|

| Resting place | Troyes |

| Nationality | French |

| Occupation | Traditionally a vintner (recently questioned, see article) |

| Known for | Writing commentaries, grammarian |

| Children | 3 daughters |

Shlomo Yitzchaki (Hebrew: רבי שלמה יצחקי; Latin: Salomon Isaacides; French: Salomon de Troyes, 22 February 1040 – 13 July 1105), today generally known by the acronym Rashi, was a medieval French rabbi, the author of comprehensive commentaries on the Talmud and Hebrew Bible.

Acclaimed for his ability to present the basic meaning of the text in a concise and lucid fashion, Rashi's commentaries appeal to both learned scholars and beginning students, and his works remain a centerpiece of contemporary Torah study. A large fraction of rabbinic literature published since the Middle Ages discusses Rashi, either using his view as supporting evidence or debating against it. His commentary on the Talmud, which covers nearly all of the Babylonian Talmud, has been included in every edition of the Talmud since its first printing by Daniel Bomberg in the 1520s. His commentaries on the Tanakh—especially his commentary on the Chumash (the "Five Books of Moses")—serves as the basis of more than 300 "supercommentaries" which analyze Rashi's choice of language and citations, penned by some of the greatest names in rabbinic literature.

Contents

Name

Rashi's surname, Yitzhaki, derives from his father's name, Yitzhak. The acronym "Rashi" stands for Rabbi Shlomo Yitzhaki, but is sometimes fancifully expanded as Rabban Shel YIsrael which means the "Rabbi of Israel", or as Rabbenu SheYichyeh (Our Rabbi, may he live). He may be cited in Hebrew and Aramaic texts as (1) "Shlomo son of Rabbi Yitzhak", (2) "Shlomo son of Yitzhak", (3) "Shlomo Yitzhaki", and myriad similar highly respectful derivatives.

In older literature, Rashi is sometimes referred to as Jarchi or Yarhi (ירחי), his abbreviated name being interpreted as Rabbi Shlomo Yarhi. This was understood to refer to the Hebrew name of Lunel in Provence, popularly derived from the occitan luna "moon", in Hebrew ירח, in which Rashi was assumed to have lived at some time or to have been born, or where his ancestors were supposed to have originated. Later Christian writers Richard Simon and Johann Christoph Wolf claimed that only Christian scholars referred to Rashi as Jarchi, and that this epithet was unknown to the Jews. Bernardo de Rossi, however, demonstrated that Hebrew scholars also referred to Rashi as Yarhi. In 1839, Leopold Zunz showed that the Hebrew usage of Jarchi was an erroneous propagation of the error by Christian writers, instead interpreting the abbreviation as it is understood today: Rabbi Shlomo Yitzhaki. The evolution of this term has been thoroughly traced.

Biography

Birth and early life

Rashi was an only child born at Troyes, Champagne, in northern France. His mother's brother was Simeon bar Isaac, rabbi of Mainz. Simon was a disciple of Gershom ben Judah, who died that same year. On his father's side, Rashi has been claimed to be a 33rd-generation descendant of Johanan HaSandlar, who was a fourth-generation descendant of Gamaliel, who was reputedly descended from the Davidic line. In his voluminous writings, Rashi himself made no such claim at all. The main early rabbinical source about his ancestry, Responsum No. 29 by Solomon Luria, makes no such claim either.

Legends

His fame later made him the subject of many legends. One tradition contends that his parents were childless for many years. Rashi's father, Yitzhak, a poor winemaker, once found a precious jewel and was approached by non-Jews who wished to buy it to adorn their idol. Yitzhak agreed to travel with them to their land, but en route, he cast the gem into the sea. Afterwards he was visited by either the Voice of God or the prophet Elijah, who told him that he would be rewarded with the birth of a noble son "who would illuminate the world with his Torah knowledge."

Another legend also states that Rashi's parents moved to Worms, Germany while Rashi's mother was pregnant. As she walked down one of the narrow streets in the Jewish quarter, she was imperiled by two oncoming carriages. She turned and pressed herself against a wall, which opened to receive her. This miraculous niche is still visible in the wall of the Worms Synagogue.

Yeshiva studies

According to tradition, Rashi was first brought to learn Torah by his father on Shavuot day at the age of five. His father was his main Torah teacher until his death when Rashi was still a youth. At the age of 17 he married and soon after went to learn in the yeshiva of Yaakov ben Yakar in Worms, returning to his wife three times yearly, for the Days of Awe, Passover and Shavuot. When Yaakov died in 1064, Rashi continued learning in Worms for another year in the yeshiva of his relative, Isaac ben Eliezer Halevi, who was also chief rabbi of Worms. Then he moved to Mainz, where he studied under another of his relatives, Isaac ben Judah, the rabbinic head of Mainz and one of the leading sages of the Lorraine region straddling France and Germany.

Rashi's teachers were students of Rabbeinu Gershom and Eliezer Hagadol, leading Talmudists of the previous generation. From his teachers, Rashi imbibed the oral traditions pertaining to the Talmud as they had been passed down for centuries, as well as an understanding of the Talmud's logic and forms of argument. Rashi took concise, copious notes from what he learned in yeshiva, incorporating this material in his commentaries. He was also greatly influenced by the exegetical principles of Menahem Kara.

Rosh yeshiva

He returned to Troyes at the age of 25, after which time his mother died, and he was asked to join the Troyes Beth din (rabbinical court). He also began answering halakhic questions. Upon the death of the head of the Bet din, Zerach ben Abraham, Rashi assumed the court's leadership and answered hundreds of halakhic queries.

At some time around 1070 he founded a yeshiva which attracted many disciples. It is thought by some that Rashi earned his living as a vintner since Rashi shows an extensive knowledge of its utensils and process, but there is no evidence for this. Most scholars and a Jewish oral tradition contend that he was a vintner. The only reason given for the centuries-old tradition that he was a vintner being not true is that the soil in all of Troyes is not optimal for growing wine grapes, claimed by the research of Haym Soloveitchik. There exists a reference to a seal said to be from his vineyard.

Although there are many legends about his travels, Rashi likely never went further than from the Seine to the Rhine; his furthest destinations were the yeshivas of Lorraine.

In 1096, the People's Crusade swept through the Lorraine, murdering 12,000 Jews and uprooting whole communities. Among those murdered in Worms were the three sons of Isaac ben Eliezer Halevi, Rashi's teacher. Rashi wrote several Selichot (penitential poems) mourning the slaughter and the destruction of the region's great yeshivot. Seven of Rashi's Selichot still exist, including Adonai Elohei Hatz'vaot, which is recited on the eve of Rosh Hashanah, and Az Terem Nimtehu, which is recited on the Fast of Gedalia.

Death and burial site

Rashi died on July 13, 1105 (Tammuz 29, 4865) at the age of 65. He was buried in Troyes. The approximate location of the cemetery in which he was buried was recorded in Seder ha-Dorot, but over time the location of the cemetery was forgotten. A number of years ago, a Sorbonne professor discovered an ancient map depicting the site of the cemetery, which lay under an open square in the city of Troyes. After this discovery, French Jews erected a large monument in the center of the square—a large, black and white globe featuring the three Hebrew letters of רשי artfully arranged counterclockwise in negative space, evoking the style of Hebrew microcalligraphy. The granite base of the monument is engraved: Rabbi Shlomo Yitzchaki — Commentator and Guide.

In 2005, Yisroel Meir Gabbai erected an additional plaque at this site marking the square as a burial ground. The plaque reads: "The place you are standing on is the cemetery of the town of Troyes. Many Rishonim are buried here, among them Rabbi Shlomo, known as Rashi the holy, may his merit protect us".

Descendants

Rashi had no male descendants. All of his three children were girls, named Yocheved, Miriam and Rachel. He invested himself in their education; his writings and the legends which surround him suggest that his daughters were well-versed in the Torah and the Talmud (at a time when women were not expected to study them) and would for instance help him when he was too weak to write. His daughters would marry his disciples; most present-day Ashkenazi rabbinical dynasties can trace their lineage back to his daughters Miriam or Yocheved.

A late-20th century legend claims that Rashi's daughters wore tefillin. While a few women in medieval Ashkenaz did wear tefillin, there is no evidence that Rashi's daughters did.

- Rashi's oldest daughter, Yocheved, married Meir ben Samuel; their four sons were Shmuel (Rashbam; born 1080), Yitzchak (Rivam; born 1090), Jacob (Rabbeinu Tam; born 1100), and Shlomo the Grammarian, all of whom were among the most prolific Tosafists. Yocheved's daughter, Channah, is reputed to have instructed the local women to recite the blessing after candle lighting (instead of before).

- Rashi's middle daughter, Miriam, married Judah ben Nathan, who completed the commentary on the Talmud Makkot. Their daughter Alvina was a learned woman whose customs served as the basis for later halakhic decisions. Their son Yom Tov later moved to Paris and headed a yeshiva there, together with his brothers Shimshon and Eliezer.

- Rashi's youngest daughter, Rachel, married (and divorced) Eliezer ben Shemiah.

Works

Responsa

About 300 of Rashi's responsa and halakhic decisions are extant. Although some may find contradictory to Rashi's intended purpose for his writings, these responsa were copied, preserved, and published by his students, grandchildren, and other future scholars. Siddur Rashi, compiled by an unknown student, also contains Rashi's responsa on prayer. Many other rulings and responsa are recorded in Mahzor Vitry. Other compilations include Sefer Hapardes, probably edited by Shemaiah of Troyes, Rashi's student, and Sefer Haorah, prepared by Nathan Hamachiri.

Rashi's writing is placed under the category of post-Talmudic, for its explanation and elaboration on the Talmud; however, he not only wrote about the meaning of Biblical and Talmudic passages, but also on liturgical texts, syntax rules, and cases regarding new religions emerging. Some say that his responsa allows people to obtain "clear pictures of his personality," and shows Rashi as a kind, gentle, humble, and liberal man. They also illustrate his intelligence and common sense.

Rashi's responsa not only addressed some of the different cases and questions regarding Jewish life and law, but it shed light into the historical and social conditions which the Jews were under during the First Crusade. He covered the following topics and themes in his responsa: linguistic focus on texts, law related to prayer, food, and the Sabbath, wine produced by non-Jews, oaths and excommunications, sales, partnerships, loans and interest, bails, communal affairs, and civil law. Rashi's responsa can be broken down into three genres: questions by contemporary sages and students regarding the Torah, the law, and other compilations.

For example, in his writing regarding relations with the Christians, he provides a guide for how one should behave when dealing with martyrs and converts, as well as the "insults and terms of [disgrace] aimed at the Jews." Stemming from the aftermath of the Crusades, Rashi wrote concerning those who were forced to convert, and the rights women had when their husbands were killed.

Rashi focused the majority of his responsa, if not all, on a "meticulous analysis of the language of the text".

Legacy

Rashi was one of the first authors to write in Old French (the language he spoke in everyday life, which he used alongside Hebrew), as most contemporary French authors instead wrote in Latin. As a consequence, besides its religious value, his work is currently valued for the insight it gives into the language and culture of Northern France in the 11th century.

Influence in non-Jewish circles

Rashi's commentaries on the Bible, especially those on the Pentateuch, circulated in many different communities. In the 12th–17th centuries, Rashi's influence spread from French and German provinces to Spain and the east. He had a tremendous influence on Christian scholars. The French monk Nicholas de Lyra of Manjacoria, who was known as the "ape of Rashi", relied on Rashi's commentary when writing his Postillae Perpetuate, one of the primary sources used in Luther's translation of the Bible. He believed that Rashi's commentaries were the "official repository of Rabbinical tradition" and significant to understanding the Bible. Rashi's commentaries became significant to humanists at this time who studied grammar and exegesis. Christian Hebraists studied Rashi's commentaries as important interpretations "authorized by the Synagogue".

Although Rashi had an influence on communities outside of Judaism, his lack of connection to science prevented him from entering the general domain, and he remained more popular among the Jewish community.

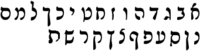

"Rashi script"

The semi-cursive typeface in which Rashi's commentaries are printed both in the Talmud and Tanakh is often referred to as "Rashi script." Despite the name, Rashi himself did not use such a script: the typeface is based on a 15th-century Sephardic semi-cursive hand, postdating Rashi's death by several hundred years. Early Hebrew typographers such as the Soncino family and Daniel Bomberg employed in their editions of commented texts (such as the Mikraot Gedolot and the Talmud, in which Rashi's commentaries prominently figure) what would become called "Rashi script" to distinguish the rabbinic commentary from the primary text proper, for which they used a square typeface.

See also

In Spanish: Rashi para niños

In Spanish: Rashi para niños