Raphael Lemkin facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Raphael Lemkin

|

|

|---|---|

| Rafał Lemkin | |

|

|

| Born | 24 June 1900 Bezwodne, Volkovyssky Uyezd, Grodno Governorate, Russian Empire

(now Zelʹva District, Grodno Region, Belarus) |

| Died | 28 August 1959 (aged 59) New York City, U.S.

|

| Nationality | Polish |

| Occupation | Lawyer |

| Known for |

|

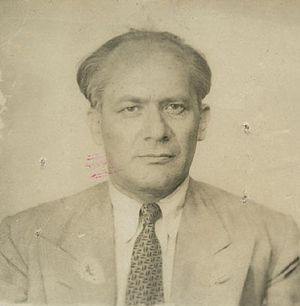

Raphael Lemkin (Polish: Rafał Lemkin; 24 June 1900 – 28 August 1959) was a Polish lawyer who is best known for coining the term genocide and initiating the Genocide Convention, an interest spurred on after learning about the Armenian genocide and finding out that no international laws existed to prosecute the Ottoman leaders who had perpetrated these crimes.

Lemkin coined genocide in 1943 or 1944 from genos (Greek: γένος, 'family, clan, tribe, race, stock, kin') and -cide (Latin: -cīdium, 'killing'). He became interested in war crimes after reading about the 1921 trial of Soghomon Tehlirian for the assassination of Talaat Pasha. He recognized the fate of Armenians as one of the most significant genocides of the 20th century.

Contents

Life

Early life

Lemkin was born Rafał Lemkin on 24 June 1900 in Bezwodne, a village in the Volkovyssky Uyezd of the Grodno Governorate of the Russian Empire (present-day Belarus). He grew up in a Polish Jewish family on a large farm near Wolkowysk and was one of three children born to Józef Lemkin and Bella née Pomeranz. His father was a farmer and his mother an intellectual, a painter, linguist, and philosophy student with a large collection of books on literature and history. Lemkin and his two brothers (Eliasz and Samuel) were homeschooled by their mother.

As a youth, Lemkin was fascinated by the subject of atrocities and would often question his mother about such events as the Sack of Carthage, Mongol invasions and conquests and the persecution of Huguenots. Lemkin apparently came across the concept of mass atrocities while, at the age of 12, reading Quo Vadis by Henryk Sienkiewicz, in particular the passage where Nero threw Christians to the lions. About these stories, Lemkin wrote, "a line of blood led from the Roman arena through the gallows of France to the Białystok pogrom." Through his writings, Lemkin demonstrates a belief central to his thinking through his life: the suffering of Jews in eastern Poland was part of a larger pattern of injustice and violence that stretched back through history and around the world.

The Lemkin family farm was located in an area in which fighting between Russian and German troops occurred during World War I. The family buried their books and valuables before taking shelter in a nearby forest. During the fighting, artillery fire destroyed their home and German troops seized their crops, horses and livestock. Lemkin's brother Samuel eventually died of pneumonia and malnutrition while the family remained in the forest.

After graduating from a local trade school in Białystok he began the study of linguistics at the Jan Kazimierz University of Lwów (now Lviv, Ukraine). He was a polyglot, fluent in nine languages and reading fourteen. His first published book was a 1926 translation of the Hayim Nahman Bialik novella Noah and Marinka from Hebrew into Polish. It was in Białystok that Lemkin became interested in laws against mass atrocities after learning about the Armenian genocide in the Ottoman Empire, then later the experience of Assyrians massacred in Iraq during the 1933 Simele massacre.

After reading about the 1921 assassination of Talat Pasha, the main perpetrator of the Armenian genocide, in Berlin by Soghomon Tehlirian, Lemkin asked Professor Juliusz Makarewicz why Talat Pasha could not have been tried for his crimes in a German court. Makarewicz, a national-conservative who believed that Jews and Ukrainians should be expelled from Poland if they refused to assimilate, answered that the doctrine of state sovereignty gave governments the right to conduct internal affairs as they saw fit: "Consider the case of a farmer who owns a flock of chickens. He kills them, and this is his business. If you interfere, you are trespassing." Lemkin replied, "But the Armenians are not chickens". His eventual conclusion was that "Sovereignty, I argued, cannot be conceived as the right to kill millions of innocent people".

Lemkin then moved on to Heidelberg University in Germany to study philosophy, returned to Lwów to study law in 1926.

Career in interwar Poland

Lemkin worked as an Assistant Prosecutor in the District Court of Brzeżany (since 1945 Berezhany, Ukraine) and Warsaw, followed by a private legal practice in Warsaw. From 1929 to 1934, Lemkin was the Public Prosecutor for the district court of Warsaw. In 1930 he was promoted to Deputy Prosecutor in a local court in Brzeżany. While Public Prosecutor, Lemkin was also secretary of the Committee on Codification of the Laws of the Republic of Poland, which codified the penal codes of Poland, and taught law at Tachkemoni College in Warsaw. Lemkin, working with Duke University law professor Malcolm McDermott, translated The Polish Penal Code of 1932 from Polish to English.

In 1933 Lemkin made a presentation to the Legal Council of the League of Nations conference on international criminal law in Madrid, for which he prepared an essay on the Crime of Barbarity as a crime against international law. In 1934 Lemkin, under pressure from the Polish Foreign Minister for comments made at the Madrid conference, resigned his position and became a private solicitor in Warsaw. While in Warsaw, Lemkin attended numerous lectures organized by the Free Polish University, including the classes of Emil Stanisław Rappaport and Wacław Makowski.

In 1937, Lemkin was appointed a member of the Polish mission to the 4th Congress on Criminal Law in Paris, where he also introduced the possibility of defending peace through criminal law. Among the most important of his works of that period are a compendium of Polish criminal fiscal law, Prawo karne skarbowe (1938) and a French-language work, La réglementation des paiements internationaux, regarding international trade law (1939).

During World War II

He left Warsaw on 6 September 1939 and made his way north-east towards Wolkowysk. He was caught between the invaders, the Germans in the west, and the Soviets who then approached from the east. Poland's independence was extinguished by terms of the pact between Stalin and Hitler. He barely evaded German capture, and traveled through Lithuania to reach Sweden by early spring of 1940. There he lectured at the University of Stockholm. Curious about the manner of imposition of Nazi rule he started to gather Nazi decrees and ordinances, believing official documents often reflected underlying objectives without stating them explicitly. He spent much time in the central library of Stockholm, gathering, translating and analysing the documents he collected, looking for patterns of German behaviour. Lemkin's work led him to see the wholesale destruction of the nations over which Germans took control as an overall aim. Some documents Lemkin analysed had been signed by Hitler, implementing ideas of Mein Kampf on Lebensraum, new living space to be inhabited by Germans. With the help of his pre-war associate McDermott, Lemkin received permission to enter the United States, arriving in 1941.

Although he managed to save his life, he lost 49 relatives in the Holocaust; The only members of Lemkin's family in Europe who survived the Holocaust were his brother, Elias, and his wife and two sons, who had been sent to a Soviet forced labor camp. Lemkin did however successfully help his brother and family to emigrate to Montreal, Quebec, Canada in 1948.

After arriving in the United States, at the invitation of McDermott, Lemkin joined the law faculty at Duke University in North Carolina in 1941. During the Summer of 1942 Lemkin lectured at the School of Military Government at the University of Virginia. He also wrote Military Government in Europe, a preliminary version of what would become, in two years, his magnum opus, entitled Axis Rule in Occupied Europe. In 1943 Lemkin was appointed consultant to the US Board of Economic Warfare and Foreign Economic Administration and later became a special adviser on foreign affairs to the War Department, largely due to his expertise in international law.

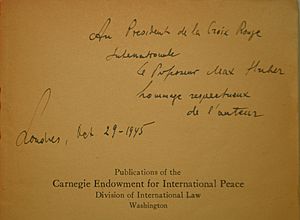

In November 1944, the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace published Axis Rule in Occupied Europe. This book included an extensive legal analysis of German rule in countries occupied by Nazi Germany during the course of World War II, along with the definition of the term genocide. Lemkin's idea of genocide as an offence against international law was widely accepted by the international community and was one of the legal bases of the Nuremberg Trials. In 1945 to 1946, Lemkin became an advisor to Supreme Court of the United States Justice and Nuremberg Trial chief counsel Robert H. Jackson. The book became one of the foundational texts in Holocaust studies, and the study of totalitarianism, mass violence, and genocide studies.

Postwar

After the war, Lemkin chose to remain in the United States. Starting in 1948, he gave lectures on criminal law at Yale University. In 1955, he became a Professor of Law at Rutgers School of Law in Newark. Lemkin also continued his campaign for international laws defining and forbidding genocide, which he had championed ever since the Madrid conference of 1933. He proposed a similar ban on crimes against humanity during the Paris Peace Conference of 1945, but his proposal was turned down.

Lemkin presented a draft resolution for a Genocide Convention treaty to a number of countries, in an effort to persuade them to sponsor the resolution. With the support of the United States, the resolution was placed before the General Assembly for consideration. The Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide was formally presented and adopted on 9 December 1948. In 1951, Lemkin only partially achieved his goal when the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide came into force, after the 20th nation had ratified the treaty.

Lemkin's broader concerns over genocide, as set out in his Axis Rule, also embraced what may be considered as non-physical, namely, psychological acts of genocide. The book also detailed the various techniques which had been employed to achieve genocide.

Between 1953 and 1957, Lemkin worked directly with representatives of several governments, such as Egypt, to outlaw genocide under the domestic penal codes of these countries. Lemkin also worked with a team of lawyers from Arab delegations at the United Nations to build a case to prosecute French officials for genocide in Algeria. He also recognized the Ukrainian Holodomor and applied the term 'genocide' in his 1953 article "Soviet Genocide in Ukraine", which he presented as a speech in New York City. Lemkin stated that the Holodomor was the third prong of Soviet Russification of Ukraine.

Death and legacy

In the last years of his life, Lemkin was living in poverty in a New York apartment. In 1959, at the age of 59, he died of a heart attack in New York City. Only several close people attended his funeral at Riverside Church. Lemkin was buried in Flushing, Queens at Mount Hebron Cemetery. At the time of his death, Lemkin left several unfinished works, including an Introduction to the Study of Genocide and an ambitious three-volume History of Genocide that contained seventy proposed chapters and a book-length analysis of Nazi war crimes at Nuremberg.

The United States, Lemkin's adopted country, did not ratify the Genocide Convention during his lifetime. He believed that his efforts to prevent genocide had failed. "The fact is that the rain of my work fell on a fallow plain," he wrote, "only this rain was a mixture of the blood and tears of eight million innocent people throughout the world. Included also were the tears of my parents and my friends." Lemkin was not widely known until the 1990s, when international prosecutions of genocide began in response to atrocities in the former Yugoslavia and Rwanda, and "genocide" began to be understood as the crime of crimes.

Recognition

For his work on international law and the prevention of war crimes, Lemkin received a number of awards, including the Cuban Grand Cross of the Order of Carlos Manuel de Cespedes in 1950, the Stephen Wise Award of the American Jewish Congress in 1951, and the Cross of Merit of the Federal Republic of Germany in 1955. On the 50th anniversary of the Convention entering into force, Lemkin was also honored by the UN Secretary-General as "an inspiring example of moral engagement." He was nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize ten times.

In 1989 he was awarded, posthumously, the Four Freedoms Award for the Freedom of Worship.

Lemkin is the subject of the plays Lemkin's House by Catherine Filloux (2005), and If The Whole Body Dies: Raphael Lemkin and the Treaty Against Genocide by Robert Skloot (2006). He was also profiled in the 2014 American documentary film, Watchers of the Sky.

Every year, The Rabbinic Call for Human Rights (T’ruah) gives the Raphael Lemkin Human Rights Award to a layperson who draws on his or her Jewish values to be a human rights leader.

On 20 November 2015, Lemkin's article Soviet genocide in Ukraine was added to the Russian index of "extremist publications," whose distribution in Russia is forbidden.

On 15 September 2018 the Ukrainian Canadian Civil Liberties Foundation (www.ucclf.ca) and its supporters in the US unveiled the world's first Ukrainian/English/Hebrew/Yiddish plaque honouring Lemkin for his recognition of the tragic famine of 1932–1933 in the Soviet Union, the Holodomor, at the Ukrainian Institute of America, in New York City, marking the 75th anniversary of Lemkin's address, "Soviet Genocide in the Ukraine".

Works

- The Polish Penal Code of 1932 and The Law of Minor Offenses. Durham, North Carolina: Duke University Press. 1939.

- Lemkin, Raphael (1933). Acts Constituting a General (Transnational) Danger Considered as Offences Against the Law of Nations (5th Conference for the Unification of Penal Law). Madrid.

- Lemkin, Raphael (1939). La réglementation des paiements internationaux; traité de droit comparé sur les devises, le clearing et les accords de paiements, les conflits des lois.. Paris: A. Pedone.

- Lemkin, Raphael (1942). Key laws, decrees and regulations issued by the Axis in occupied Europe. Washington: Board of Economic Warfare, Blockade and Supply Branch, Reoccupation Division.

- Lemkin, Raphael (1943). Axis rule in occupied Europe : laws of occupation, analysis of government, proposals for redress. Clark, N.J: Lawbook Exchange. ISBN 978-1-58477-901-8.

- Lemkin, Raphael (April 1945). "Genocide - A Modern Crime". Free World (New York) 9 (4): 39–43.

- Lemkin, Raphael (April 1946). "The Crime of Genocide". American Scholar 15 (2): 227–30.

- "Genocide: A Commentary on the Convention". Yale Law Journal 58 (7): 1142–56. June 1949. doi:10.2307/792930. https://digitalcommons.law.yale.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=4830&context=ylj.

- Stone, Dan (2013). The Holocaust, Fascism, and memory : essays in the history of ideas (Chapt 2). Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-1-137-02952-2.

- Lemkin, Raphael (2014). Soviet Genocide in the Ukraine. Kingston: Kashtan Press.

See also

In Spanish: Raphael Lemkin para niños

In Spanish: Raphael Lemkin para niños

- Crimes against humanity

- War crime

- International criminal law

- Genocide

- Armenian genocide

- Holodomor

- The Holocaust

- Porajmos

- Hersch Lauterpacht