Pontiac's War facts for kids

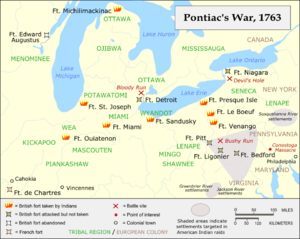

Pontiac's Rebellion was a war launched in 1763 by Native Americans ("Indians") who were dissatisfied with British rule in the Great Lakes region and the Ohio Country after the British victory in the French and Indian War. The war began in 1763 when Native Americans attacked a number of British forts and Anglo-American settlements; hostilities came to an end after British army expeditions in 1764 led to peace negotiations. The war was a failure for the Indians in that it did not drive away the British, but the widespread uprising prompted the British government to modify the policies that had provoked the conflict.

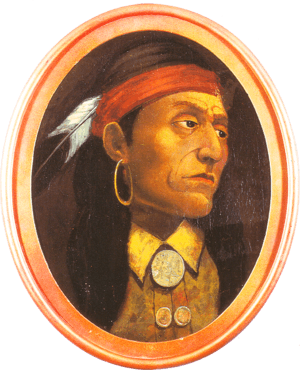

The war is named after its most famous participant, the Ottawa leader Pontiac; variations include "Pontiac's Conspiracy" and "Pontiac’s Uprising." Scholars have long questioned the appropriateness of naming the war after Pontiac, since no single Native American instigated or led the conflict. Furthermore, descriptions such as "conspiracy" and "rebellion"—first used in an era when white historians wrote from an overtly racist perspective—suggest an illegitimate revolt against British authority. Alternate titles such as the "Western Indians' Defensive War of 1763" have not caught on; the predominant usage among historians today is "Pontiac's War."

Today, perhaps the best-known incident from the war is when British officers at Fort Pitt attempted to infect the attacking Indians with blankets that had been exposed to smallpox. (See "Siege of Fort Pitt" below.)

Contents

Origins

After the French and Indian War, Native Americans who had been allies of the defeated French found themselves increasingly dissatisfied with the attitudes and policies of the victorious British. In essence, while the French had treated certain Indian tribes as allies, the British approach was to treat them as subjects.

The architect of the new Indian policy, British General Jeffrey Amherst, decided to cut back on the gifts and provisions customarily distributed to the Indians, which he considered to be bribes. Amherst also outlawed the sale of alcohol to Indians, which created much resentment. Additionally, the French had made gunpowder and ammunition readily available, which were needed by the Indians to hunt to provide food for their families and skins for trade. However, Amherst did not trust his former Indian adversaries, and restricted the distribution of gunpowder and ammunition. Pontiac and other Indian leaders were certain that the British intended to enslave or destroy them.

At the same time, a religious awakening was sweeping through Indian settlements in the Ohio Country and Great Lakes region. At the center of this phenomenon was Neolin, called the Delaware Prophet, who called upon Indians to shun the trade goods, alcohol, and weapons of the whites. Merging elements from Christianity into his traditional religious beliefs, Neolin told his followers that the Master of Life was unhappy with the way that the Indians had been living, and that changes needed to be made. It was a powerful message for people who had fallen on hard times.

"Rebellion"

The rebellion began at Fort Detroit under the local leadership of Pontiac, and quickly spread to other British forts in the region. Eight forts fell to Indian attackers; others, including Fort Detroit and Fort Pitt, were unsuccessfully besieged. While it is tempting to conclude that this uprising was coordinated as part of a grand operation, historian Gregory Dowd argues that there is no reliable evidence of this. Likewise, although it was widely assumed at the time that Frenchmen were involved in the "conspiracy," this is a matter of speculation as well. Rather than the product of a master plan, it is possible that Pontiac’s Rebellion evolved spontaneously, as Pontiac’s actions at Detroit inspired other already discontented Indians to similarly take up arms against the British.

Siege of Fort Detroit

On April 27, 1763, Pontiac spoke at a council about 10 miles below Detroit. Using the words of Neolin to inspire his listeners, Pontiac convinced a number of Ottawas, Ojibwas, Potawatomis, and Hurons to join him in an attempt to seize Fort Detroit. On May 7, Pontiac entered the fort with about 300 men, armed with sawed-off muskets and other weapons hidden under blankets, determined to take the fort by surprise. However, the British commander had apparently been informed of Pontiac’s plan, and the garrison of about 120 men was armed and ready. Pontiac withdrew and, two days later, laid siege to the fort. A number of British soldiers and settlers in the area outside the fort were captured or killed. Eventually more than 900 Indian warriors from a half-dozen tribes joined the siege.

Late in July, British reinforcements arrived at Fort Detroit. On July 31, 1763, about 250 men attempted to make a surprise attack on Pontiac’s encampment. Pontiac was ready and waiting, and defeated the British at the Battle of Bloody Run. However, the situation at the fort remained a stalemate, and Pontiac’s influence among his followers began to wane. Groups of Indians began to abandon the siege, some of them making peace with the British before departing. On October 31, 1763, finally convinced that the French in Illinois would not come to his aid, Pontiac lifted the siege and removed to the Maumee River, where he continued to scheme against the British.

Siege of Fort Pitt

Fort Pitt, with a garrison of 330 men (and over 200 women and children inside), was attacked on June 22, 1763, primarily by Delaware (Lenape) Indians. Too strong to be taken by force, the fort was kept under siege throughout July. Meanwhile, Delaware and Shawnee war parties raided deep into the Pennsylvania settlements, taking captives and killing unknown numbers of men, women, and children who were living on what was, a generation earlier, Indian land. Panicked settlers fled eastwards.

On June 24, 1763, in a now infamous incident, the commander of Fort Pitt gave representatives of the besieging Delawares two blankets that had been exposed to smallpox, in hopes of spreading the disease to the Indians in order to end the siege. Modern polemical accounts of Indian/white relations often cite this incident as an example of genocide. However, although Indians in the area did contract smallpox, it is impossible to verify how many people (if any) contracted the disease as a result of the Fort Pitt incident; the disease was already in the area and may have easily reached the Indians through other vectors. Jeffrey Amherst’s name is usually associated with this incident, although the first record of Amherst suggesting trying to spread smallpox to the Indians is from the summer of 1764, after the commander at Fort Pitt had already made this attempt, apparently on his own initiative.

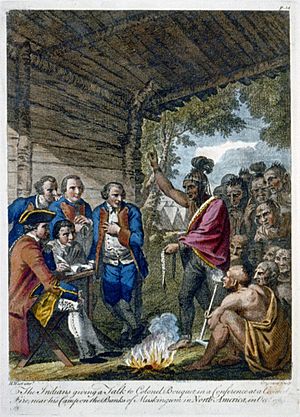

On August 1, 1763, most of the Indians broke off the siege at Fort Pitt in order to intercept a body of 500 British troops marching to the fort under Colonel Henry Bouquet. On August 5, these two forces met at the Battle of Bushy Run. Bouquet fought off the Indian attack and relieved Fort Pitt on August 20.

Other forts

- Fort Sandusky (on the site of Sandusky, Ohio) was taken on May 16, 1763 by Wyandot Indians, using the same stratagem that had failed in Detroit. The Indians had gained entry to the fort under the pretense of holding a council, and then seized the commander and killed the fifteen-man garrison. A great number of British traders were put to death as well, and the fort was burned.

- Fort St. Joseph (on the site of the present Niles, Michigan) was captured on May 25, 1763 by the same method as at Sandusky. The commander was seized by Potawatomis, and most of the fifteen-man garrison was killed outright.

- The third fort to fall was Fort Miami (on the site of Fort Wayne, Indiana), on May 27, 1763. The commander was lured out of the fort by his Indian mistress and shot dead by Miami Indians. The nine-man garrison surrendered after the fort was surrounded.

- Fort Ouiatanon (about 5 miles southwest of the present Lafayette, Indiana) was taken by Indians on June 1, 1763. Soldiers were lured outside for a council, and the entire twenty-man garrison was taken captive without bloodshed.

- Fort Michilimackinac (Mackinac), Michigan, was the largest fort taken by surprise. On June 4, 1763, local Ojibwas had staged a kind of lacrosse game with visiting Sauks. The soldiers watched the game, as they had done on previous occasions. The ball was hit through the open gate of the fort; the teams rushed in and were then handed weapons previously smuggled into the fort by Indian women. About fifteen men of the 35 man garrison were killed in the struggle; five more were later executed.

- Fort Venango (near the site of the present Venango, Pennsylvania) was taken around June 16, 1763 by Senecas. The entire twelve-man garrison was killed.

- Fort Le Boeuf (on the site of Waterford, Pennsylvania) was attacked on June 18, possibly by the same Senecas who had destroyed Fort Venango. Most of the twelve-man garrison escaped to Fort Pitt.

- Fort Presque Isle (on the site of Erie, Pennsylvania) was surrounded by about 250 Ottawas, Ojibwas, Wyandots, and Senecas on June 19, 1763. After holding out for two days, the garrison of approximately sixty men surrendered on the condition that they could return to Fort Pitt. Most were instead murdered after emerging from the fort.

Fort Niagara, one of the most critical western forts, was not assaulted, but on September 14, 1763 at least 300 Senecas, Ottawas, and Ojibwas attacked a supply train along the Niagara Falls portage. Two companies sent from Fort Niagara to rescue the supply train were also defeated. Seventy-two soldiers and wagoners were killed in these actions, which Anglo-Americans called the "Devil's Hole Massacre."

Although the main attacks on Fort Detroit and Fort Pitt had failed, nearly every minor fort attacked was captured in 1763, about 200 settlers and traders were killed, and in property destroyed or plundered the English lost about £100,000, the greatest loss in men and property being in western Pennsylvania. Total Indian losses are unknown.

Aftermath

This war worsened Britain's financial health and resulted in the Proclamation of 1763, preventing the colonists from moving westward.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Rebelión de Pontiac para niños

In Spanish: Rebelión de Pontiac para niños