Pipefish facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Pipefish |

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Alligator pipefish (Syngnathoides biaculeatus) | |

| Scientific classification |

|

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Actinopterygii |

| Order: | Syngnathiformes |

| Family: | Syngnathidae |

| Subfamily: | Syngnathinae Bonaparte, 1831 |

| Genera | |

|

See text. |

|

Pipefishes or pipe-fishes (Syngnathinae) are a subfamily of small fishes, which, together with the seahorses and seadragons (Phycodurus and Phyllopteryx), form the family Syngnathidae.

Contents

Description

Pipefish look like straight-bodied seahorses with tiny mouths. The name is derived from the peculiar form of the snout, which is like a long tube, ending in a narrow and small mouth which opens upwards and is toothless. The body and tail are long, thin, and snake-like. They each have a highly modified skeleton formed into armored plating. This dermal skeleton has several longitudinal ridges, so a vertical section through the body looks angular, not round or oval as in the majority of other fishes.

A dorsal fin is always present, and is the principal (in some species, the only) organ of locomotion. The ventral fins are consistently absent, and the other fins may or may not be developed. The gill openings are extremely small and placed near the upper posterior angle of the gill cover.

Many are very weak swimmers in open water, moving slowly by means of rapid movements of the dorsal fin. Some species of pipefish have prehensile tails, as in seahorses. The majority of pipefishes have some form of a caudal fin (unlike seahorses), which can be used for locomotion. See fish anatomy for fin descriptions. Some species of pipefish have more developed caudal fins, such as the group collectively known as flagtail pipefish, which are quite strong swimmers.

Habitat and distribution

Most pipefishes are marine dwellers; only a few are freshwater species. They are abundant on coasts of the tropical and temperate zones. Most species of pipefish are usually 35–40 cm (14–15.5 in) in length and generally inhabit sheltered areas in coral reefs or seagrass beds.

Habitat loss and threats

Due to their lack of strong swimming ability pipefish are often found in shallow waters that are easily disturbed by industrial runoffs and human recreation. Shorelines are also affected by boats and drag lines that move shoreline sediment. These disturbances cause a decrease in seagrasses and eelgrasses that are vital in pipefish habitats. Due to the pipefish’s narrow distribution they are less able to adapt to new habitats. Another factor that affects pipefish populations is their use in Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM) remedies, despite the lack of evidence of efficacy beyond placebo. Syngnathidae in general are in high demand for pseudo-scientific medicinal cures but pipefish are even more exploited because of a belief in their higher level of potency (because they are longer than the more common variety of seahorses). Aquarium trade of pipefish has also increased in recent years. Local and national fishing restrictions have been put into effect to help protect this vulnerable order of fish.

Reproduction and parental care

Pipefishes, like their seahorse relatives, leave most of the parenting duties to the male, which provides all of the postzygotic care for its offspring, supplying them with nutrients and oxygen through a placenta-like connection. It broods the offspring either on distinct region of its body or in a brood pouch. Brood pouches vary significantly among different species of pipefish, but all contain a small opening through which female eggs can be deposited. The location of the brood pouch can be along the entire underside of the pipefish or just at the base of the tail, as with seahorses. Pipefish in the genus Syngnathus have a brood pouch with a ventral seam that can completely cover all of their eggs when sealed. In males without these pouches, eggs adhere to a strip of soft skin on the ventral surface of their bodies that does not contain any exterior covering. The evolution of male brooding in pipefish is thought to be a result of the reproductive advantage granted to pipefish ancestors that learned to deposit their eggs onto the males, who could escape predation and protect them. Furthermore, the ability to transfer immune information from both the mother (in the egg) and the father (in the pouch), unlike other chordates in which only the mother can transfer immune information, is believed to have an additive beneficial effect on offspring immunity.

A physical limit exists for the number of eggs a male pipefish can carry. Females can often produce more eggs than males can accommodate inside their brood pouches, resulting in more eggs than can be cared for. Other factors may restrict female reproductive success, including male pregnancy length and energy investment in progeny. Because the pipefish embryos develop within the male, feeding on nutrients supplied by him, male pipefish invest more energy than females in each zygote. Additionally, they invest more energy per unit time than females throughout each breeding season. As a result, some males may consume their embryos rather than continuing to rear them under situations in which their bodies are exhausted of resources, to regain energy. Pregnant male pipefish can absorb nutrients from their broods, in a manner found in many other families of fish. The smallest eggs in a brood of various egg sizes usually have lower survival rates than larger ones, due to the larger eggs being competitively superior and more likely to develop into mature adults.

Young are born free-swimming with relatively little or no yolk sac, and begin feeding immediately. From the time they hatch, they are independent of their parents, which at that time may view them as food. Some fry have short larval stages and live as plankton for a short while. Others are fully developed but miniature versions of their parents, assuming the same behaviors as their parents immediately.

Pair bonding varies wildly between different species of pipefish. While some are monogamous or seasonally monogamous, others are not.

Many species exhibit polyandry, a breeding system in which one female mates with two or more males. This tends to occur with greater frequency in internal-brooding species of pipefishes than with external-brooding ones due to limitation in male brood capacity. Polyandrous species are also more likely to have females with complex signals such as ornaments. For example, the polyandrous Gulf pipefish (Syngnathus scovelli) displays considerable sexual dimorphic characteristics such as larger ornament area and number, and body size.

Genera

- Subfamily Syngnathinae (pipefishes and seadragons)

- Genus Acentronura Kaup, 1853

- Genus Amphelikturus Parr, 1930

- Genus Anarchopterus Hubbs, 1935

- Genus Apterygocampus Weber, 1913

- Genus Bhanotia Hora, 1926

- Genus Bryx Herald, 1940

- Genus Bulbonaricus Herald, 1953

- Genus Campichthys Whitley, 1931

- Genus Choeroichthys Kaup, 1856

- Genus Corythoichthys Kaup, 1853

- Genus Cosmocampus Dawson, 1979

- Genus Doryichthys Kaup, 1853

- Genus Doryrhamphus Kaup, 1856

- Genus Dunckerocampus Whitley, 1933

- Genus Enneacampus Dawson, 1981

- Genus Entelurus Duméril, 1870

- Genus Festucalex Whitley, 1931

- Genus Filicampus Whitley, 1948

- Genus Halicampus Kaup, 1856

- Genus Haliichthys Gray, 1859

- Genus Heraldia Paxton, 1975

- Genus Hippichthys Bleeker, 1849—river pipefishes

- Genus Histiogamphelus McCulloch, 1914

- Genus Hypselognathus Whitley, 1948

- Genus Ichthyocampus Kaup, 1853

- Genus Idiotropiscis Whitely, 1947

- Genus Kaupus Whitley, 1951

- Genus Kimblaeus Dawson, 1980

- Genus Kyonemichthys Gomon, 2007

- Genus Leptoichthys Kaup, 1853

- Genus Leptonotus Kaup, 1853

- Genus Lissocampus Waite and Hale, 1921

- Genus Maroubra Whitley, 1948

- Genus Micrognathus Duncker, 1912

- Genus Microphis Kaup, 1853—freshwater pipefishes

- Genus Minyichthys Herald and Randall, 1972

- Genus Mitotichthys Whitley, 1948

- Genus Nannocampus Günther, 1870

- Genus Nerophis Rafinesque, 1810

- Genus Notiocampus Dawson, 1979

- Genus Penetopteryx Lunel, 1881

- Genus Phoxocampus Dawson, 1977

- Genus Phycodurus Gill, 1896—leafy seadragon

- Genus Phyllopteryx Swainson, 1839—seadragons

- Genus Pseudophallus Herald, 1940—fluvial pipefishes

- Genus Pugnaso Whitley, 1948

- Genus Siokunichthys Herald, 1953

- Genus Solegnathus Swainson, 1839

- Genus Stigmatopora Kaup, 1853

- Genus Stipecampus Whitley, 1948

- Genus Syngnathoides Bleeker, 1851

- Genus Syngnathus Linnaeus, 1758

- Genus Trachyrhamphus Kaup, 1853

- Genus Urocampus Günther, 1870

- Genus Vanacampus Whitley, 1951

Images for kids

-

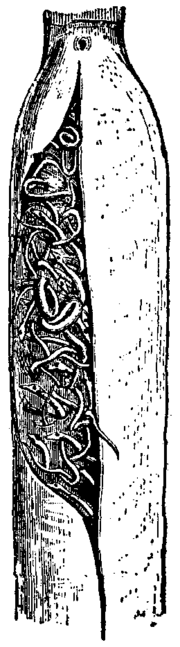

The subcaudal pouch of the male of the black-striped pipefish (Syngnathus abaster)

See also

In Spanish: Pez aguja para niños

In Spanish: Pez aguja para niños