Palisades Amusement Park facts for kids

| Previously known as Park on the Palisades, Schenck Brothers Palisade Park | |

|

|

| Location | Cliffside Park-Fort Lee, New Jersey, U.S. |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 40°49′41″N 73°58′40″W / 40.8281°N 73.9778°W |

| Status | Closed |

| Opened | 1898 |

| Closed | September 12, 1971 |

| Owner | Nicholas and Joseph Schenck, Jack and Irving Rosenthal |

| Slogan | Come on over! |

| Operating season | Weekend before Easter to Sunday after Labor Day |

| Area | New York metropolitan area |

| Attractions | |

| Total | 45-50 (rides varied from season to season) |

| Roller coasters | 5 |

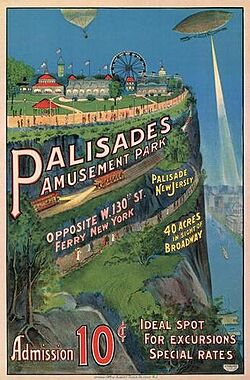

Palisades Amusement Park was a 38-acre amusement park located in Bergen County, New Jersey, across the Hudson River from New York City. It was located atop the New Jersey Palisades lying partly in Cliffside Park and partly in Fort Lee. The park operated from 1898 until 1971, remaining one of the most visited amusement parks in the country until the end of its existence. After the park closed in 1971, a high-rise luxury apartment complex was built on its site.

Contents

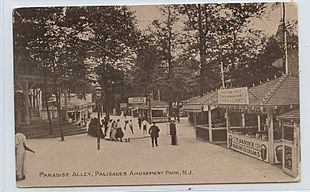

Trolley park era: 1898-1910

The park overlooked the Hudson River on 30 acres (12 ha) of New Jersey riverfront land. It straddled what is now Cliffside Park and Fort Lee, and facing the northern end of Manhattan.

In 1898, before common use of automobiles, the Bergen County Traction Company conceived the park as a trolley park to attract evening and weekend riders. It was originally known as "The Park on the Palisades".

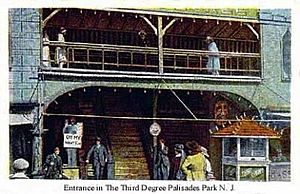

In 1908, the trolley company sold the park to August Neumann and Frank Knox, who hired Alven H. Dexter to manage it. Dexter imported a crude assortment of attractions which included a Ferris wheel, a baby parade, and diving horses.

Schenck brothers' ownership: 1910-1934

By 1908, the park was renamed Palisades Amusement Park, and the new owners began adding amusement rides and attractions.

In 1910 the park was purchased by Nicholas and Joseph Schenck and their Realty Trust Company. The Schencks were brothers who were active in the nascent motion picture industry in nearby Fort Lee, as well as operated the Fort George Amusement Park in New York City, across the Hudson River to the east. They renamed the park once again, naming it Schenck Bros. Palisade Park.

In 1912 the park added a salt-water swimming pool. It was filled by pumping water from the saline Hudson River, 200 feet (60 m) below in the town of Edgewater. This pool, 400 by 600 feet (120 meters by 180 meters) in surface area, was advertised as the largest salt-water wave pool in the nation. Behind the water falls were huge pontoons that rose up and down as they rotated, creating a one-foot wave in the pool.

As the park added more and more attractions, it became so famous by the 1920s that the Borough of Palisades Park, located just west of the amusement park, considered changing its name to avoid confusion among amusement park visitors.

In 1928 the park introduced the Cyclone roller coaster, the third of Harry Traver's "Terrifying Triplets". Due to the high maintenance costs, the ride was removed six years later.

Rosenthal brothers' ownership: 1934-1971

In 1934 or 1935, Nicholas and Joseph Schenck sold the site for $450,000 to Jack and Irving Rosenthal. The brothers and entrepreneurs had made a fortune as concessionaires at Coney Island in Brooklyn. They also owned some concessions and a carousel at Savin Rock Park in Connecticut. The Rosenthals built the Coney Island Cyclone, a wooden coaster (completely different from the Travers' Triplets), in 1927.

In 1935 the park was partially damaged by fire. In 1944, a second fire forced the park to close until the start of the 1945 season.

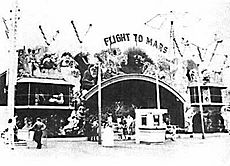

The Rosenthals reverted the park's name to the more recognizable Palisades Amusement Park. One of the many attractions, rebuilt and redesigned by construction superintendent Joe McKee, was the Skyrocket roller coaster. The Rosenthals named the newly repaired coaster the "Cyclone", after their Coney Island coaster. In 1958, Joe built the Wild Mouse roller coaster with his construction foreman Bert Whitworth,.

The park's reputation and attendance continued to grow throughout the 1950s and 1960s, largely due to saturation advertising and the continued success of the park's music pavilion and Caisson bar erected during that time.

During the mid-1950s the park started featuring rock and roll shows hosted by local radio announcers Clay Cole and "Cousin Brucie" Morrow, and starting during the 1960s, Motown musical acts were performed there. Advertisements for the park were frequently printed in the back pages of 1950s and 1960s comic books. The Rosenthals realized that youths in the New York metropolitan area represented the largest single market for comic books in the nation, and that comic book advertising was a cheap way to reach thousands of potential customers.

Segregation

In 1946, the park formed the Sun and Surf Club and restricted pool access to members only. In the book Palisades Amusement Park: A Century of Fond Memories, the author Vince Gargiulo writes that "In reality, the club allowed park officials to discriminate according to the color of the patron's skin". He cites an example in July 1946, where eight black and two white people entered the park together; the white people were allowed to purchase tickets while the black people were prohibited from doing so. In response, African Americans started protesting against the Palisades Amusement Park pool's segregation policy; some protesters held signs that stated "Protest Jim Crow".

On July 13, 1947, Melba Valle, a 22-year-old African-American woman, tried to use a pool admission ticket from a Caucasian friend, but was not allowed to enter the pool. Valle was then "'forcibly dragged and ejected' from the Park", as described in several newspapers; as a result, the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) started protesting at the Palisades Amusement Park entrance. Even though police detained 11 CORE members, the group stated that they would protest at the park entrance on Sundays, and would only stop their protests when the pool started allowing African Americans.

The protesters handed out the following flyer in 1947, which is now on exhibit in the Fort Lee Museum.

DON'T GET COOL

AT PALISADES POOL

Palisades Pool, in violation of the New Jersey Civil Rights Law, bars Negroes and persons with dark skins.

Such a person is told that a club exists and only members can use the pool.

Yet white persons who are not "members" are regularly admitted and then handed a "membership" card inside.Irving Rosenthal, the Park's owner, refused to cease racial discrimination, although it violates the New Jersey law.

Members of our interracial group who tried peacefully to gain admittance to the pool

have been manhandled by the Park's private guards and by Fort Lee police.On July 27 of that year, a Negro was blackjacked from behind by a park representative

while other park "goons" were shoving him on a bus.On August 3, eleven of the CORE group were arrested on trumped up charges, and two were beaten by the police.

The policy was dropped by the 1950s.

"Palisades Park" song and boom in popularity

In 1962, Chuck Barris composed and Freddy Cannon recorded a song about the park entitled "Palisades Park". The song was an up-tempo rock and roll tune initiated by a distinctive organ part. The song also incorporated amusement park sound effects. "Palisades Park" received nationwide radioplay and increased the park's fame even more. The "Palisades Park" song generated a surge of park visitors.

There was a hole in the fence behind the amusement park's music stage, which was used by local children to sneak into the park without paying admission. Although the Rosenthal brothers knew about the hole, they did not repair it. Unlike some modern amusement parks that sell passes to enter the grounds themselves, Palisades Amusement Park also charged individual fees for each ride and attraction inside the park. Irving Rosenthal, who loved children even though he had none of his own, allowed this "secret" entrance to remain and instructed security personnel to ignore anyone sneaking through it. He felt that children, who had little money to start with, would be more willing to spend their limited funds inside the park if they got in for free.

Irving Rosenthal also printed free-admission offers on matchbooks and in other media. He owned an advertising company that put up billboards known as "three sheeters" all over New York City.

Parking was free for the same reasons. However, as the park began attracting bigger and bigger crowds in later years, the on-site parking lot became less and less adequate, often rapidly filling to capacity. An overflow parking lot was opened at the bottom of the cliff in Edgewater, and shuttle buses carried visitors up to the park. The overflow lot sometimes also reached capacity, and when this happened, motorists were directed to park on local streets anywhere between the nearby George Washington Bridge and the Lincoln Tunnel several miles south. This reduced parking for local residents and businesses, as well as added to street congestion.

From 1947 to 1971 Palisades Park averaged 6 million visitors. Peak attendance was reached in 1969 with 10 million visitors. Radio and television commercials broadcast in the greater New York area encouraged the public to, "Come on over!" They did just that.

Demise

Three factors contributed to the eventual closing of Palisades Amusement Park: inadequate parking facilities; growing uncertainty about the park's future; and an increase in the number of incidents where visitors got injured or killed.

By 1967, Jack Rosenthal had died of Parkinson's disease, leaving his brother Irving as sole owner. Irving, in his 70s, was not expected to manage the park for much longer. Without family heirs, it was unclear as to who would eventually assume ownership. Meanwhile, the park had become so popular that the towns of Cliffside Park and Fort Lee saw increased and worsening congestion from park patrons who did not live in the area.

Local residents objected to the traffic jams, litter, changing racial demographics, and other effects of the park's immense popularity. They demanded action from local elected officials. Developers wanted to profit by the Palisades' view of Manhattan, and they successfully pressured the local government to re-zone the amusement park site for high-rise apartment housing and condemn it under eminent domain.

During the next few years, the land was surveyed by a number of builders who made lucrative offers, but Rosenthal tried to postpone the park's inevitable closing and refused to sell. During the heyday of "Palisades Park" in the 1950s and 1960s, Irving would refer to Fort Lee as his town.

In January 1971 a Texas developer, Winston-Centex Corporation, acquired the property for $12.5 million and agreed to lease it back to Irving Rosenthal so that Palisades Amusement Park could operate for one final season. The park permanently closed on Sunday, September 12, 1971. The last person to swim in the famous "world's largest outdoor saltwater pool" was Curt Kellinger, son of long time park employee and pool manager George Kellinger, Sr.

After it closed, Morgan "Mickey" Hughes and Fletch Creamer, Jr. tried to reopen the park for one more season and obtained a lease from Winston-Centex. However, the town of Fort Lee would not issue a business license until the next spring, and even then the town could not guarantee such a license. The buildings were subsequently demolished; the rides sold, dismantled and transported to other amusement operators in the United States and Canada. The towns of Cliffside Park and Fort Lee considered using the park's salt-water swimming pool for municipal recreation, only to find that its filtration system had been damaged beyond repair by vandals.

Four high-rise luxury apartment buildings stand on the old park site today. The first two built were Winston Towers. Carlyle Towers followed and then the Royal Buckingham. In 1998, on the centennial of the opening of the original Park on the Palisades, Winston Towers management dedicated a monument to Palisades Amusement Park on its property. The monument is a small park, with the names of the rides inscribed on its bricks, named "The Little Park of Memories." In June 2014, five original roller coaster cars from The Cyclone that were "gathering dust for decades" were returned to Bergen County from Pennsylvania, and were planned to undergo a restoration project, more than 40 years after the park's closing. Though the cars are not functional, they were anticipated to be publicly showcased and displayed.