PS General Slocum facts for kids

|

|

Quick facts for kids History |

|

|---|---|

| Name | General Slocum |

| Namesake | Henry Warner Slocum |

| Owner | Knickerbocker Steamship Company |

| Port of registry | United States |

| Builder | Divine Burtis, Jr., of Brooklyn, New York |

| Laid down | December 23, 1890 |

| Launched | April 18, 1891 |

| Maiden voyage | June 25, 1891 |

| Fate |

|

| General characteristics | |

| Class and type | Sidewheeler passenger ship |

| Tonnage | 1,284 grt |

| Length | 264 ft (80 m) |

| Beam | 37.5 ft (11.4 m) |

| Draft | 7.5 ft (2.3 m) unloaded; 8 ft (2.4 m) - 8.5 ft (2.6 m) loaded |

| Depth | 12.3 ft (3.7 m) |

| Decks | three decks |

| Installed power | 1 × 53 in bore, 12 ft stroke single cylinder vertical beam steam engine |

| Propulsion | Sidewheel boat; each wheel had 26 paddles and was 31 ft (9.4 m) in diameter. |

| Speed | 16 knots (30 km/h) |

| Crew | 22 |

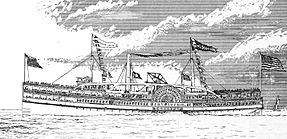

The PS General Slocum was a sidewheel passenger steamboat built in Brooklyn, New York, in 1891. During her service history, she was involved in a number of mishaps, including multiple groundings and collisions.

On June 15, 1904, General Slocum caught fire and sank in the East River of New York City. At the time of the accident, she was on a chartered run carrying members of St. Mark's Evangelical Lutheran Church (German Americans from Little Germany, Manhattan) to a church picnic. An estimated 1,021 of the 1,342 people on board died. The General Slocum disaster was the New York area's worst disaster in terms of loss of life until the September 11, 2001 attacks. It is the worst maritime disaster in the city's history, and the second worst maritime disaster on United States waterways. The events surrounding the General Slocum fire have been explored in a number of books, plays, and movies.

Contents

Construction and design

The hull of General Slocum was built by Divine Burtis, Jr., a Brooklyn boatbuilder who was awarded the contract on February 15, 1891; the superstructure was built by John E. Hoffmire & Son. Her keel was 235 feet (72 m) long and the hull was 37.5 feet (11.4 m) wide constructed of white oak and yellow pine. General Slocum measured 1,284 tons gross, and had a hull depth of 12.3 feet (3.7 m). General Slocum was constructed with three decks (main, promenade, and hurricane), three watertight compartments, and 250 electric lights. She drew 7.5 ft (2.3 m) unladen and was 250 ft (76 m) long overall.

General Slocum was powered by a single-cylinder, surface-condensing vertical-beam steam engine with a 53 inches (1.3 m) bore and 12 foot (3.7 m) stroke, built by W. & A. Fletcher Company of Hoboken, New Jersey. Steam was supplied by two boilers at a working pressure of 52 pounds per square inch (360 kPa). General Slocum was a sidewheel boat. Each wheel had 26 paddles and was 31 feet (9.4 m) in diameter. Her maximum speed was about 16 knots (30 km/h). The ship was usually crewed by a contingent of 22, including Captain William H. Van Schaick and two pilots. She had a legal capacity of 2,500 passengers.

Cabins, storeroom, and machinery spaces were below the main deck. Crew quarters were the second compartment aft from the bow, with a hatch and ladder leading to the main deck. Aft of the quarters was the "forward cabin", also fitted with a companionway to the main deck; it was originally intended to be a cabin space, but had been used as a storeroom and lamp room. The forward cabin also housed the ship's steering engine and dynamo. The forward cabin, measuring approximately 30 ft × 28 ft (9.1 m × 8.5 m) (length × width), was used for general storage and to store and refuel the ship's lamps from oil barrels kept there. Oil had been spilled on the deck of the Lamp Room numerous times, and it was frequented by crew who habitually used open flames in the room. Aft of the forward cabin was the machinery space for engines and boilers. The stern compartment below the main deck (aft of the machinery) was used as an aftersaloon.

The forward part of the main deck was enclosed just forward of the companionway to the forward cabin. The promenade deck, above the main deck, was open except for a small section amidships. The hurricane deck, above the promenade, was where the lifeboats and life rafts were stowed. The pilot house was above the hurricane deck, with a small stateroom immediately aft.

Service history

General Slocum was named for Civil War General and New York Congressman Henry Warner Slocum. She was owned by the Knickerbocker Steamboat Company. She operated in the New York City area as an excursion steamer for the next 13 years under the same ownership.

General Slocum experienced a series of mishaps following her launch in 1891. Four months after her launching, she ran aground off Rockaway. Tugboats had to be used to pull her free.

A number of incidents occurred during 1894. On July 29, while returning from Rockaway with about 4,700 passengers, General Slocum struck a sandbar with enough force that her electrical generator went out. The next month, General Slocum ran aground off Coney Island during a storm. During this grounding, the passengers had to be transferred to another ship. In September 1894, General Slocum collided with the tug R. T. Sayre in the East River, with General Slocum sustaining substantial damage to her steering.

In July 1898, another collision occurred when General Slocum collided with Amelia near Battery Park. On August 17, 1901, while carrying what was described as 900 intoxicated anarchists from Paterson, New Jersey, some of the passengers started a riot on board and tried to take control of the vessel. The crew fought back and kept control of the ship. The captain docked the ship at the police pier, and 17 men were taken into custody by the police.

In June 1902, General Slocum ran aground with 400 passengers aboard. With the vessel unable to be freed, the passengers had to camp out overnight while the ship remained stuck.

1904 disaster

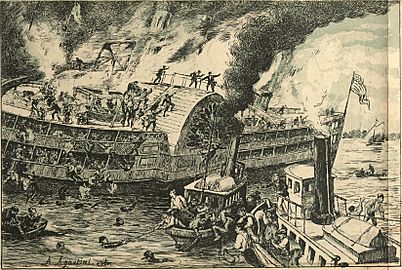

General Slocum worked as a passenger ship, taking people on excursions around New York City. On Wednesday, June 15, 1904, the ship had been chartered for $350 by St. Mark's Evangelical Lutheran Church in the Little Germany district of Manhattan. This was an annual rite for the group, which had made the trip for 17 consecutive years, a period when German settlers moved from Little Germany to the Upper East and West sides. Nearly 1,400 passengers, mostly women and children, boarded General Slocum, which was to sail up the East River and then eastward across the Long Island Sound to Locust Grove, a picnic site in Eatons Neck, Long Island. The official post-disaster report stated there were 1,358 passengers and 30 officers and crew; fewer than 150 of the passengers were estimated to be adult males over 21. Of those on board, there were 957 deaths and 180 injuries. Less than twenty minutes elapsed between the start of the fire and the collapse of the hurricane deck.

The fire

The ship got underway from the recreation pier at Third Street on the East River at 9:30 am; it passed west of Blackwell Island (now Roosevelt Island) and turned east, remaining south of Wards Island. As it was passing East 90th Street, a fire started in the forward cabin or Lamp Room, the third compartment aft from the bow under the main deck; the fire was possibly caused by a discarded cigarette or match. The disastrous fire was fueled by the straw, oily rags, and lamp oil strewn around the room. The first notice of a fire was at 10 am; eyewitnesses claimed the initial blaze began in various locations, including a paint locker filled with flammable liquids and a cabin filled with gasoline. Passengers on the main deck were aware of the fire at the entrance to Hell Gate. Captain Van Schaick was not notified until 10 minutes after the fire was discovered. A 12-year-old boy had tried to warn him earlier, but was not believed. After he was notified of the fire, Van Schaick ordered full speed ahead; approximately 30 seconds later, he directed the pilot to beach the ship on North Brother Island. Following this last command, Van Schaick descended to the hurricane deck and remained there until he was able to jump into shallow water after the ship was beached.

Although the captain was ultimately responsible for the safety of passengers, the owners had made no effort to maintain or replace the ship's safety equipment. The main deck was equipped with a standpipe connected to a steam pump, but the fire hose attached to the forward end of the standpipe, a 100 ft (30 m) length of "cheap unlined linen", had been allowed to rot and burst in several places. When the crew tried to put out the fire; they were unable to attach a rubber hose because the coupling of the linen hose remained attached to the standpipe. The ship was also equipped with hand pumps and buckets, but they were not used during the disaster; the crew gave up firefighting efforts after failing to attach the rubber hose. The crew had not practiced a fire drill that year, and the lifeboats were tied up and inaccessible. (Some claim they were wired and painted in place.)

Survivors reported that the life preservers were useless and fell apart in their hands, while desperate mothers placed life jackets on their children and tossed them into the water, only to watch in horror as their children sank instead of floating. Most of those on board were women and children who, like most Americans of the time, could not swim; victims found that their heavy wool clothing absorbed water and weighed them down in the river.

It was discovered that Nonpareil Cork Works, supplier of cork materials to manufacturers of life preservers, placed 8 oz (230 g) iron bars inside the cork materials to meet minimum content requirements (6 lb (2.7 kg) of "good cork") at the time. Nonpareil's deception was revealed by David Kahnweiler's Sons, who inspected a shipment of 300 cork blocks. Many of the life preservers had been filled with cheap and less effective granulated cork and brought up to proper weight by the inclusion of the iron weights. Canvas covers, rotted with age, split and scattered the powdered cork. Managers of the company (Nonpareil Cork Works) were indicted but not convicted. The life preservers on the Slocum had been manufactured in 1891 and had hung above the deck, unprotected from the elements, for 13 years.

Beaching on North Brother Island

Captain Van Schaick decided to continue his course rather than run the ship aground or stop at a nearby landing. By going into headwinds and failing to immediately ground the ship, he fanned the fire and promoted its spread from fore to aft; the investigating commission later faulted Van Schaick for passing up opportunities to beach the vessel in Little Hell Gate (west of the Sunken Meadows) or the Bronx Bills (east of the Sunken Meadows), which also would have put the prevailing winds astern, keeping flames from spreading along the length of the ship. Van Schaick later argued he was trying to avoid having the fire spread to riverside buildings and oil tanks. Flammable paint also helped the fire spread out of control, which was driven aft mainly along the port side of the ship; passengers, who were on the upper promenade and hurricane decks, were forced into the aft starboard quarter.

Ten minutes after the ship was beached, the fire had essentially engulfed the vessel; no more than twenty minutes had elapsed since the first flames came up from the Lamp Room. Some passengers jumped into the river to escape the fire, but the heavy women's clothing of the day made swimming almost impossible and dragged them underwater to drown. An estimated 100 to 500 died when the overloaded starboard section of the hurricane deck collapsed, casting those passengers into deep water, and others were battered by the still-turning paddles as they tried to escape into the water or over the sides. The commission estimated that 400 to 600 people drowned after the ship was beached, as they jumped off the aft portion of the boat into deep water; those jumping off the bow landed in shallower water.

General Slocum remained beached on North Brother Island for approximately 90 minutes before breaking free and drifting east for approximately 1 mi (1.6 km); by the time she sank in shallow water off the Bronx shore at Hunts Point, an estimated 1,021 . There were 431 survivors. The actions of two tugboats which arrived a few minutes after the Slocum was beached were credited with saving between 200 and 350 people.

The 1904 Coast Guard Report estimated the following figures for casualties of a total of 1,388 persons involved in the disaster:

| Status | Passengers | Crew |

|---|---|---|

| Total on board | 1,358 | 30 |

| Adults | 613 | – |

| Children | 745 | – |

| Dead | 955 | 2 |

| Identified dead | 893 | 2 |

| Missing & unidentified dead | 62 | 0 |

| Injured | 175 | 5 |

| Uninjured | 228 | 23 |

The captain lost sight in one eye owing to the fire. Reports indicate that Captain Van Schaick deserted General Slocum as soon as it settled, jumping into a nearby tug, along with several crew. He was hospitalized at Lebanon Hospital.

Many acts of heroism were committed by the passengers, witnesses, and emergency personnel. Staff and patients from the hospital on North Brother Island participated in the rescue efforts, forming human chains and pulling victims from the water.

Aftermath

Eight people were indicted by a federal grand jury after the disaster: the captain, two inspectors, and the president, secretary, treasurer, and commodore of the Knickerbocker Steamship Company. Only Captain Van Schaick was convicted. He was found guilty on one of three charges: criminal negligence, for failing to maintain proper fire drills and fire extinguishers. The jury could not reach a verdict on the other two counts of manslaughter. He was sentenced to 10 years imprisonment. He spent three years and six months at Sing Sing prison before he was paroled. President Theodore Roosevelt declined to pardon Captain Van Schaick. He was not released until the federal parole board under the William Howard Taft administration voted to free him on August 26, 1911. He was pardoned by President Taft on December 19, 1912; the pardon became effective on Christmas Day. After his death in 1927, Schaick was buried in Oakwood Cemetery (Troy, New York).

The Knickerbocker Steamship Company, which owned the ship, paid a relatively small fine despite evidence that they might have falsified inspection records. The disaster motivated federal and state regulation to improve the emergency equipment on passenger ships.

The neighborhood of Little Germany, which had been in decline for some time before the disaster as residents moved uptown, almost disappeared afterward. With the trauma and arguments that followed the tragedy and the loss of many prominent settlers, most of the Lutheran Germans remaining in the Lower East Side eventually moved uptown. The church whose congregation chartered the ship for the fateful voyage was converted to a synagogue in 1940 after the area was settled by Jewish residents.

The victims were interred in cemeteries around New York, with 58 identified victims buried in the Cemetery of the Evergreens, and 46 identified victims buried in Green-Wood Cemetery, both in Brooklyn. Many victims were buried at Lutheran Cemetery in Middle Village, Queens (now Lutheran All Faiths Cemetery) where an annual memorial ceremony is held at the historical marker.

In 1906, a marble memorial fountain was erected in the north central part of Tompkins Square Park in Manhattan by the Sympathy Society of German Ladies, with the inscription: "They are Earth's purest children, young and fair."

The sunken remains of General Slocum were salvaged and converted into a 625-gross register ton barge named Maryland, which sank in 1909 and again in the Atlantic Ocean off the southeast coast of New Jersey near Strathmere and Sea Isle City during a storm on December 4, 1911, while carrying a cargo of coal. All four people aboard Maryland survived the sinking.

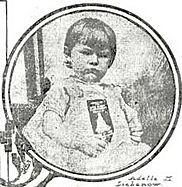

Survivors

On January 26, 2004, the last surviving passenger from General Slocum, Adella Wotherspoon (née Liebenow), died at the age of 100. At the time of the disaster, she was a six-month-old infant. Wotherspoon was the youngest survivor of the tragedy that took the lives of her two older sisters. When she was one year old, she unveiled the Steamboat Fire Mass Memorial on June 15, 1905, at Lutheran All Faiths Cemetery, in Middle Village, Queens. Before Wotherspoon's death, the previous oldest survivor was Catherine Connelly (née Uhlmyer) (1893–2002) who was 11 years old at the time of the accident.

In popular culture

Literature

- 1922 – A few references are made to the disaster in James Joyce's Ulysses, the events of which take place on the following day (June 16, 1904).

- 1925 – A few references to the disaster occur in John Dos Passos' novel Manhattan Transfer.

- 1939 – Journalist Nat Ferber's autobiography, I Found Out: A Confidential Chronicle of the Twenties, begins with his reporting on the General Slocum tragedy.

- 1975 – Robert Shea and Robert Anton Wilson's satirical The Illuminatus! Trilogy briefly mentions the disaster as attributable to the 23 enigma, since 19+04=23. Cartwright alleges that the disaster was an Illuminati technique for "transcendental illumination" through human sacrifice.

- 1996 – Eric Blau's novel The Hero of the Slocum Disaster is based on the disaster; it was later adapted by Patrick Tull and Emily King into a one-person play.

- 2000 – The story of General Slocum was described as an "Avoidable Catastrophe" in Bob Fenster's book, Duh! The Stupid History of the Human Race, in Part One, which discusses stories involving stupidity.

- 2003 – Ship Ablaze by Edward O'Donnell is a detailed history of the event.

- 2003 – The disaster is featured in one of the chapters of author Clive Cussler's book The Sea Hunters 2 when he finds the wreckage of the barge Maryland, which was the converted Slocum after she was salvaged.

- 2003 – The protagonist of Pete Hamill's Forever: A Novel describes the event both as the worst disaster in New York's history at its time, and the point at which Germans left Kleindeutschland for Yorkville, effectively vacating the present-day Lower East Side, which was then adopted by Central European Jews.

- 2004 – The 2005 Hugo Award-nominated novella Time Ablaze by Michael A. Burstein (Analog, June 2004) concerns a time traveler who comes to record the disaster. The story was published to commemorate the 100th anniversary of the disaster.

- 2006 – The General Slocum disaster is at the center of the novel Kiss Me, I'm Dead, by J.G. Sandom, also published as The Unresolved using the pen name of T.K. Welsh.

- 2008 – The General Slocum disaster plays a prominent role in Richard Crabbe's novel Hell's Gate.

- 2009 – The General Slocum tragedy is described in detail in Glenn Stout's 2009 biography of Gertrude Ederle, Young Woman and the Sea. Stout uses the incident, in which many women and young children drowned, to help explain the history of how women, including Ederle, were afforded opportunities to learn to swim during the early part of the century.

- 2010–2012 – The disaster plays a prominent role in the novels In the Shadow of Gotham (2010) and Secret of the White Rose (2012) by Stefanie Pintoff.

- 2011 – The sinking and the spirits of the dead near the site of the sinking at the Hell Gate Bridge are a major plot line in the supernatural novel Dead Waters by Anton Strout.

- 2013 – In the Dean Koontz novel Innocence, deaths caused by the sinking of General Slocum prompted the construction of secret rooms dedicated to the memory of a family lost.

Film, television, music

- 1904 – The Slocum Disaster - This silent American Mutoscope and Biograph Company (#2932) documentary short filmed by G. W. Bitzer features footage of the collecting of bodies on North Brother Island, the temporary morgue at the offices of Public Charites, and mourners at St. Marks German Evangelical Lutheran Church, taken on June 16 and 17, 1904 and released that same month on the 22nd.

- 1904 – The American composer Charles Ives (1874–1954) wrote the tone poem "The General Slocum", a musical portrait of the disaster.

- 1915 – Regeneration is an early gangster film directed by Raoul Walsh and produced by William Fox. The film was lost until the 1970s. It has a lengthy scene in which an excursion picnic ship burns in dramatic fashion while passengers jump overboard, an obvious reference to the General Slocum disaster. Walsh shot the scene in New York, not far from where the real disaster occurred.

- 1934 – The first scenes of the film Manhattan Melodrama recreated the disaster.

- 1998 – German television produced and aired Die Slocum brennt! (The Slocum is on Fire!), an hour-long documentary by Christian Baudissin about the disaster and its impact on the German community of New York.

- 2001 – A description of the disaster and the following events, in comparison with the September 11 attacks, is given by David Rakoff in an episode of the radio program This American Life.

- 2002 – The General Slocum disaster was featured in the documentary My Father's Gun.

- 2004 – Ship Ablaze was a documentary made by History Channel, with production help from NFL Films, featuring a filmed reenactment of the disaster along with interviews of the two remaining General Slocum survivors. The documentary takes its name from the book by Edward O'Donnell, who is interviewed in it.

- 2004 – Fearful Visitation, New York's Great Steamboat Fire of 1904, produced by Philip Dray and Hank Linhart, running time 53 minutes, premiered at the New-York Historical Society for the 100-year commemoration in 2004, and was broadcast on PBS. It features interviews with the last two living survivors and historians Ed O'Donnell, Kenneth T. Jackson, and Lucy Sante.

- 2012 – The disaster was featured in Season 4, Episode 3 of the program Mysteries at the Museum.

- 2017 – The American Housewife TV series episode on May 2 featured a child cast member who had a morbid fear of water which derived from reading about the sinking of General Slocum. She cited several facts about the event.

- 2017 – History Retold: Fire at Sea is a documentary that describes the disaster among other disasters involving ships catching fire at sea.

- 2022 – The folk music group The Longest Johns reference the sinking in their song "Downed and Drowned."

See also

In Spanish: PS General Slocum para niños

In Spanish: PS General Slocum para niños