Nostradamus facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Michel de Nostredame

|

|

|---|---|

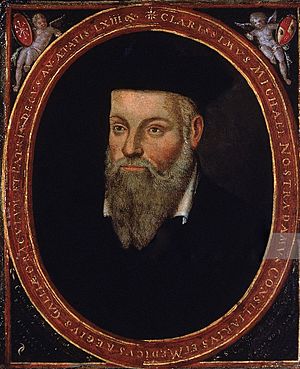

Nostradamus: original portrait by his son Cesar, c. 1614, nearly fifty years after his death

|

|

| Born | 14 or 21 December 1503 |

| Died | 1 or 2 July 1566 (aged 62) Salon-de-Provence, Provence, Kingdom of France

|

| Occupation |

|

| Known for | Prophecy, treating plague |

| Signature | |

Michel de Nostredame (December 1503 – July 1566), usually Latinised as Nostradamus, was a French astrologer, apothecary, physician, and reputed seer, who is best known for his book Les Prophéties (published in 1555), a collection of 942 poetic quatrains allegedly predicting future events.

Nostradamus's father's family had originally been Jewish, but had converted to Catholic Christianity a generation before Nostradamus was born. He studied at the University of Avignon, but was forced to leave after just over a year when the university closed due to an outbreak of the plague. He worked as an apothecary for several years before entering the University of Montpellier, hoping to earn a doctorate, but was almost immediately expelled after his work as an apothecary (a manual trade forbidden by university statutes) was discovered. He first married in 1531, but his wife and two children died in 1534 during another plague outbreak. He fought alongside doctors against the plague before remarrying to Anne Ponsarde, with whom he had six children. He wrote an almanac for 1550 and, as a result of its success, continued writing them for future years as he began working as an astrologer for various wealthy patrons. Catherine de' Medici became one of his foremost supporters. His Les Prophéties, published in 1555, relied heavily on historical and literary precedent, and initially received mixed reception. He suffered from severe gout toward the end of his life, which eventually developed into edema. He died on 1 or 2 July 1566. Many popular authors have retold apocryphal legends about his life.

In the years since the publication of his Les Prophéties, Nostradamus has attracted many supporters, who, along with some of the popular press, credit him with having accurately predicted many major world events. Academic sources reject the notion that Nostradamus had any genuine supernatural prophetic abilities and maintain that the associations made between world events and Nostradamus's quatrains are the result of (sometimes deliberate) misinterpretations or mistranslations. These academics also argue that Nostradamus's predictions are characteristically vague, meaning they could be applied to virtually anything, and are useless for determining whether their author had any real prophetic powers.

Contents

Life

Childhood

Nostradamus was born on either 14 or 21 December 1503 in Saint-Rémy-de-Provence, Provence, France, where his claimed birthplace still exists, and baptized Michel. He was one of at least nine children of notary Jaume (or Jacques) de Nostredame and Reynière, granddaughter of Pierre de Saint-Rémy who worked as a physician in Saint-Rémy. Jaume's family had originally been Jewish, but his father, Cresquas, a grain and money dealer based in Avignon, had converted to Catholicism around 1459–60, taking the Christian name "Pierre" and the surname "Nostredame" (Our Lady), the saint on whose day his conversion was solemnised. The earliest ancestor who can be identified on the paternal side is Astruge of Carcassonne, who died about 1420. Michel's known siblings included Delphine, Jean (c. 1507–1577), Pierre, Hector, Louis, Bertrand, Jean II (born 1522) and Antoine (born 1523). Little else is known about his childhood, although there is a persistent tradition that he was educated by his maternal great-grandfather Jean de St. Rémy—a tradition which is somewhat undermined by the fact that the latter disappears from the historical record after 1504 when the child was only one year old.

Student years

At the age of 14, Nostradamus entered the University of Avignon to study for his baccalaureate. After little more than a year (when he would have studied the regular trivium of grammar, rhetoric and logic rather than the later quadrivium of geometry, arithmetic, music, and astronomy/astrology), he was forced to leave Avignon when the university closed its doors during an outbreak of the plague. After leaving Avignon, Nostradamus, by his own account, traveled the countryside for eight years from 1521 researching herbal remedies. In 1529, after some years as an apothecary, he entered the University of Montpellier to study for a doctorate in medicine. He was expelled shortly afterwards by the student procurator, Guillaume Rondelet, when it was discovered that he had been an apothecary, a "manual trade" expressly banned by the university statutes, and had been slandering doctors. The expulsion document, BIU Montpellier, Register S 2 folio 87, still exists in the faculty library. However, some of his publishers and correspondents would later call him "Doctor". After his expulsion, Nostradamus continued working, presumably still as an apothecary, and became famous for creating a "rose pill" that purportedly protected against the plague.

Marriage and healing work

In 1531 Nostradamus was invited by Jules-César Scaliger, a leading Renaissance scholar, to come to Agen. There he married a woman of uncertain name (possibly Henriette d'Encausse), with whom he had two children. In 1534 his wife and children died, presumably from the plague. After their deaths, he continued to travel, passing through France and possibly Italy.

On his return in 1545, he assisted the prominent physician Louis Serre in his fight against a major plague outbreak in Marseille, and then tackled further outbreaks of disease on his own in Salon-de-Provence and in the regional capital, Aix-en-Provence. Finally, in 1547, he settled in Salon-de-Provence in the house which exists today, where he married a rich widow named Anne Ponsarde, with whom he had six children—three daughters and three sons. Between 1556 and 1567 he and his wife acquired a one-thirteenth share in a huge canal project, organised by Adam de Craponne, to create the Canal de Craponne to irrigate the largely waterless Salon-de-Provence and the nearby Désert de la Crau from the river Durance.

Occultism

After another visit to Italy, Nostradamus began to move away from medicine and toward the "occult". Following popular trends, he wrote an almanac for 1550, for the first time in print Latinising his name to Nostradamus. He was so encouraged by the almanac's success that he decided to write one or more annually. Taken together, they are known to have contained at least 6,338 prophecies, as well as at least eleven annual calendars, all of them starting on 1 January and not, as is sometimes supposed, in March. It was mainly in response to the almanacs that the nobility and other prominent persons from far away soon started asking for horoscopes and "psychic" advice from him, though he generally expected his clients to supply the birth charts on which these would be based, rather than calculating them himself as a professional astrologer would have done. When obliged to attempt this himself on the basis of the published tables of the day, he frequently made errors and failed to adjust the figures for his clients' place or time of birth.

He then began his project of writing a book of one thousand mainly French quatrains, which constitute the largely undated prophecies for which he is most famous today. Feeling vulnerable to opposition on religious grounds, however, he devised a method of obscuring his meaning by using "Virgilianised" syntax, word games and a mixture of other languages such as Greek, Italian, Latin, and Provençal. For technical reasons connected with their publication in three instalments (the publisher of the third and last instalment seems to have been unwilling to start it in the middle of a "Century," or book of 100 verses), the last fifty-eight quatrains of the seventh "Century" have not survived in any extant edition.

The quatrains, published in a book titled Les Prophéties (The Prophecies), received a mixed reaction when they were published. Some people thought Nostradamus was a servant of evil, a fake, or insane, while many of the elite evidently thought otherwise. Catherine de' Medici, wife of King Henry II of France, was one of Nostradamus's greatest admirers. After reading his almanacs for 1555, which hinted at unnamed threats to the royal family, she summoned him to Paris to explain them and to draw up horoscopes for her children. At the time, he feared that he would be beheaded, but by the time of his death in 1566, Queen Catherine had made him Counselor and Physician-in-Ordinary to her son, the young King Charles IX of France.

Some accounts of Nostradamus's life state that he was afraid of being persecuted for heresy by the Inquisition, but neither prophecy nor astrology fell in this bracket, and he would have been in danger only if he had practised magic to support them. In 1538 he came into conflict with the Church in Agen after an Inquisitor visited the area looking for anti-Catholic views. His brief imprisonment at Marignane in late 1561 was solely because he had violated a recent royal decree by publishing his 1562 almanac without the prior permission of a bishop.

Final years and death

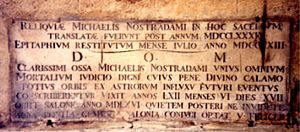

By 1566, Nostradamus' gout, which had plagued him painfully for many years and made movement very difficult, turned into edema. In late June he summoned his lawyer to draw up an extensive will bequeathing his property plus 3,444 crowns (around US$300,000 today), minus a few debts, to his wife pending her remarriage, in trust for her sons pending their twenty-fifth birthdays and her daughters pending their marriages. This was followed by a much shorter codicil. On the evening of 1 July, he is alleged to have told his secretary Jean de Chavigny, "You will not find me alive at sunrise." The next morning he was reportedly found dead, lying on the floor next to his bed and a bench (Presage 141 [originally 152] for November 1567, as posthumously edited by Chavigny to fit what happened). He was buried in the local Franciscan chapel in Salon (part of it now incorporated into the restaurant La Brocherie) but re-interred during the French Revolution in the Collégiale Saint-Laurent, where his tomb remains to this day.

Works

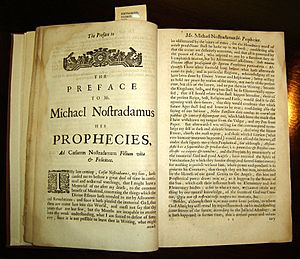

In The Prophecies Nostradamus compiled his collection of major, long-term predictions. The first installment was published in 1555 and contained 353 quatrains. The third edition, with three hundred new quatrains, was reportedly printed in 1558, but now survives as only part of the omnibus edition that was published after his death in 1568. This version contains one unrhymed and 941 rhymed quatrains, grouped into nine sets of 100 and one of 42, called "Centuries".

Given printing practices at the time (which included type-setting from dictation), no two editions turned out to be identical, and it is relatively rare to find even two copies that are exactly the same. Certainly there is no warrant for assuming—as would-be "code-breakers" are prone to do—that either the spellings or the punctuation of any edition are Nostradamus's originals.

The Almanacs, by far the most popular of his works, were published annually from 1550 until his death. He often published two or three in a year, entitled either Almanachs (detailed predictions), Prognostications or Presages (more generalised predictions).

Nostradamus was not only a diviner, but a professional healer. It is known that he wrote at least two books on medical science. One was an extremely free translation (or rather a paraphrase) of The Protreptic of Galen (Paraphrase de C. GALIEN, sus l'Exhortation de Menodote aux estudes des bonnes Artz, mesmement Medicine), and in his so-called Traité des fardemens (basically a medical cookbook containing, once again, materials borrowed mainly from others), he included a description of the methods he used to treat the plague, including bloodletting, none of which apparently worked. The same book also describes the preparation of cosmetics.

A manuscript normally known as the Orus Apollo also exists in the Lyon municipal library, where upwards of 2,000 original documents relating to Nostradamus are stored under the aegis of Michel Chomarat. It is a purported translation of an ancient Greek work on Egyptian hieroglyphs based on later Latin versions, all of them unfortunately ignorant of the true meanings of the ancient Egyptian script, which was not correctly deciphered until Champollion in the 19th century.

Since his death, only the Prophecies have continued to be popular, but in this case they have been quite extraordinarily so. Over two hundred editions of them have appeared in that time, together with over 2,000 commentaries. Their persistence in popular culture seems to be partly because their vagueness and lack of dating make it easy to quote them selectively after every major dramatic event and retrospectively claim them as "hits".

Origins of The Prophecies

Nostradamus claimed to base his published predictions on judicial astrology—the astrological 'judgment', or assessment, of the 'quality' (and thus potential) of events such as births, weddings, coronations etc.—but was heavily criticised by professional astrologers of the day such as Laurens Videl for incompetence and for assuming that "comparative horoscopy" (the comparison of future planetary configurations with those accompanying known past events) could actually predict what would happen in the future.

Research suggests that much of his prophetic work paraphrases collections of ancient end-of-the-world prophecies (mainly Bible-based), supplemented with references to historical events and anthologies of omen reports, and then projects those into the future in part with the aid of comparative horoscopy. Hence the many predictions involving ancient figures such as Sulla, Gaius Marius, Nero, and others, as well as his descriptions of "battles in the clouds" and "frogs falling from the sky". Astrology itself is mentioned only twice in Nostradamus's Preface and 41 times in the Centuries themselves, but more frequently in his dedicatory Letter to King Henry II. In the last quatrain of his sixth century he specifically attacks astrologers.

His historical sources include easily identifiable passages from Livy, Suetonius' The Twelve Caesars, Plutarch and other classical historians, as well as from medieval chroniclers such as Geoffrey of Villehardouin and Jean Froissart. Many of his astrological references are taken almost word for word from Richard Roussat's Livre de l'estat et mutations des temps of 1549–50.

One of his major prophetic sources was evidently the Mirabilis Liber of 1522, which contained a range of prophecies by Pseudo-Methodius, the Tiburtine Sibyl, Joachim of Fiore, Savonarola and others (his Preface contains 24 biblical quotations, all but two in the order used by Savonarola). This book had enjoyed considerable success in the 1520s, when it went through half a dozen editions, but did not sustain its influence, perhaps owing to its mostly Latin text (mixed with ancient Greek and modern French and Provençal), Gothic script and many difficult abbreviations. Nostradamus was one of the first to re-paraphrase these prophecies in French, which may explain why they are credited to him. Modern views of plagiarism did not apply in the 16th century; authors frequently copied and paraphrased passages without acknowledgement, especially from the classics. The latest research suggests that he may in fact have used bibliomancy for this—randomly selecting a book of history or prophecy and taking his cue from whatever page it happened to fall open at.

Further material was gleaned from the De honesta disciplina of 1504 by Petrus Crinitus, which included extracts from Michael Psellos's De daemonibus, and the De Mysteriis Aegyptiorum (Concerning the mysteries of Egypt), a book on Chaldean and Assyrian magic by Iamblichus, a 4th-century Neo-Platonist. Latin versions of both had recently been published in Lyon, and extracts from both are paraphrased (in the second case almost literally) in his first two verses, the first of which is appended to this article. While it is true that Nostradamus claimed in 1555 to have burned all of the occult works in his library, no one can say exactly what books were destroyed in this fire.

Only in the 17th century did people start to notice his reliance on earlier, mainly classical sources.

Nostradamus's reliance on historical precedent is reflected in the fact that he explicitly rejected the label "prophet" (i.e.

Given this reliance on literary sources, it is unlikely that Nostradamus used any particular methods for entering a trance state, other than contemplation, meditation and incubation. His sole description of this process is contained in 'letter 41' of his collected Latin correspondence. The popular legend that he attempted the ancient methods of flame gazing, water gazing or both simultaneously is based on a naive reading of his first two verses, which merely liken his efforts to those of the Delphic and Branchidic oracles. The first of these is reproduced at the bottom of this article and the second can be seen by visiting the relevant facsimile site (see External Links). In his dedication to King Henry II, Nostradamus describes "emptying my soul, mind and heart of all care, worry and unease through mental calm and tranquility", but his frequent references to the "bronze tripod" of the Delphic rite are usually preceded by the words "as though" (compare, once again, External References to the original texts).

See also

In Spanish: Nostradamus para niños

In Spanish: Nostradamus para niños