Norway Debate facts for kids

The Norway Debate, sometimes called the Narvik Debate, was a momentous debate in the British House of Commons from 7 to 9 May 1940, during the Second World War. The official title of the debate, as held in the Hansard parliamentary archive, is Conduct of the War. The debate was initiated by an adjournment motion enabling the Commons to freely discuss the progress of the Norwegian campaign. The debate quickly brought to a head widespread dissatisfaction with the conduct of the war by Neville Chamberlain's government.

At the end of the second day, there was a division of the House for the members to hold a no confidence motion. The vote was won by the government but by a drastically reduced majority. That led on 10 May to Chamberlain resigning as prime minister and the replacement of his war ministry by a broadly based coalition government, which, under Winston Churchill governed the United Kingdom until after the end of the war in Europe in May 1945.

Chamberlain's government was criticised not only by the Opposition but also by respected members of his own Conservative Party. The Opposition forced the vote of no confidence, in which over a quarter of Conservative members voted with the Opposition or abstained, despite a three-line whip. There were calls for national unity to be established by formation of an all-party coalition but it was not possible for Chamberlain to reach agreement with the opposition Labour and Liberal parties. They refused to serve under him, although they were willing to accept another Conservative as prime minister. After Chamberlain resigned as prime minister (he remained Conservative Party leader until October 1940), they agreed to serve under Churchill.

Contents

Background

In 1937, Neville Chamberlain, then Chancellor of the Exchequer, succeeded Stanley Baldwin as prime minister, leading a National Government overwhelmingly composed of Conservatives but supported by small National Labour and Liberal National parties. It was opposed by the Labour and Liberal parties. Since assuming power in Germany in 1933, the Nazi Party had pushed an irredentist foreign policy. Chamberlain initially attempted to avert war by a policy of appeasement, such as the Munich Agreement, but this was abandoned after Germany abandoned diplomatic means and became more overtly expansionist with the occupation of Czechoslovakia in March 1939.

One of the strongest critics of both appeasement and German aggression was Conservative backbencher Winston Churchill who, although he was one of the country's most prominent political figures, had last held government office in 1929. After Germany invaded Poland on 1 September 1939, the United Kingdom and France declared war on Germany two days later. Chamberlain thereupon created a war cabinet into which he invited Churchill as First Lord of the Admiralty. It was at this point that a government supporter (possibly David Margesson, the Government Chief Whip) noted privately:

For two-and-a-half years, Neville Chamberlain has been Prime Minister of Great Britain. During this period Great Britain has suffered a series of diplomatic defeats and humiliations, culminating in the outbreak of European war. It is an unbroken record of failure in foreign policy, and there has been no outstanding success at home to offset the lack of it abroad. ... Yet it is probable that Neville Chamberlain still retains the confidence of the majority of his fellow country-men and that, if it were possible to obtain an accurate test of the feelings of the electorate, Chamberlain would be found the most popular statesman in the land.

Once Germany had rapidly overrun Poland in September 1939, there was a sustained period of military inactivity for over six months dubbed the "Phoney War". On 3 April 1940, Chamberlain said in an address to the Conservative National Union that Adolf Hitler, the German dictator, "had missed the bus". Only six days later, on 9 April, Germany launched an attack in overwhelming force on neutral and unprepared Norway after swiftly occupying Denmark. In response, Britain deployed military forces to assist the Norwegians.

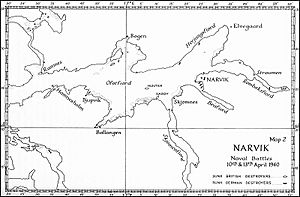

Churchill, as First Lord of the Admiralty, had direct responsibility for the conduct of naval operations in the Norwegian campaign. Before the German invasion, he had pressed the Cabinet to ignore Norway's neutrality, mine its territorial waters and be prepared to seize Narvik, in both cases to disrupt the export of Swedish iron ore to Germany during winter months, when the Baltic Sea was frozen. He had, however, advised that a major landing in Norway was not realistically within Germany's powers. Apart from the naval victory in the Battles of Narvik, the Norwegian campaign went badly for the British forces, generally because of poor planning and organisation but essentially because military supplies were inadequate and, from 27 April, the Anglo-French forces were obliged to evacuate.

When the House of Commons met on Thursday, 2 May, Labour leader Clement Attlee asked: "Is the Prime Minister now able to make a statement on the position in Norway?" Chamberlain was reluctant to discuss the military situation because of the security factors involved but did express a hope that he and Churchill would be able to say much more next week. He went on to make an interim statement of affairs but was not forthcoming about "certain operations (that) are in progress (as) we must do nothing which might jeopardise the lives of those engaged in them". He asked the House to defer comment and question until next week. Attlee agreed and so did Liberal leader Archibald Sinclair, except that he requested a debate on Norway lasting more than a single day.

Attlee then presented Chamberlain with a private notice in which he requested a schedule for next week's Commons business. Chamberlain announced that a debate on the general conduct of the war would commence on Tuesday, 7 May. The debate was keenly anticipated in both Parliament and the country. In his diary entry for Monday, 6 May, Chamberlain's Assistant Private Secretary John Colville wrote that all interest centred on the debate. Obviously, he thought, the government would win through but after facing some very awkward points about Norway. Some of Colville's colleagues including Lord Dunglass, who was Chamberlain's Parliamentary Private Secretary (PPS) at the time, considered the government position to be sound politically, but less so in other respects. Colville worried that "the confidence of the country may be somewhat shaken".

7 May: first day of the debate

Preamble and other business

The Commons sitting on Tuesday, 7 May 1940, began at 14:45 with Speaker Edward FitzRoy in the Chair. There followed some private business matters and numerous oral answers to questions raised, many of those being about the British Army.

With these matters completed, the debate on the Norwegian campaign began with a routine adjournment motion (i.e., "that this house do now adjourn"). Under Westminster rules, in debates like this which are held to allow for wide-ranging discussion of a variety of topics, the issue is not usually put to a vote.

At 15:48, Captain David Margesson, the Government Chief Whip, made the adjournment motion. The House proceeded to openly discuss "Conduct of the War", specifically the progress of the Norwegian campaign, and Chamberlain rose to make his opening statement.

Chamberlain's opening speech

Chamberlain began by reminding the House of his statement on Thursday, 2 May, five days earlier, when it was known that British forces had been withdrawn from Åndalsnes. He was now able to confirm that they had also been withdrawn from Namsos to complete the evacuation of Allied forces from central and southern Norway (the campaign in northern Norway continued). Chamberlain attempted to treat the Allied losses as unimportant and claimed that British soldiers "man for man (were) superior to their foes". He praised the "splendid gallantry and dash" of the British forces but acknowledged they were "exposed ... to superior forces with superior equipment".

Chamberlain then said he proposed "to present a picture of the situation" and to "consider certain criticisms of the government". He stated that "no doubt" the withdrawal had created a shock in both the House and the country. At this point, the interruptions began as a Labour member shouted: "All over the world".

Chamberlain sarcastically responded that "ministers, of course, must be expected to be blamed for everything". This provoked a heated reaction with several members derisively shouting: "They missed the bus!" The Speaker had to call on members not to interrupt, but they continued to repeat the phrase throughout Chamberlain's speech and he reacted with what has been described as "a rather feminine gesture of irritation". He was eventually forced to defend the original usage of the phrase directly, claiming that he would have expected a German attack on the Allies at the outbreak of war when the difference in armed power was at its greatest.

Chamberlain's speech has been widely criticised. Roy Jenkins called it "a tired, defensive speech which impressed nobody". Liberal MP Henry Morris-Jones said Chamberlain looked "a shattered man" and spoke without his customary self-assurance. When Chamberlain insisted that "the balance of advantage lay on our side", Liberal MP Dingle Foot could not believe what he was hearing and said Chamberlain was denying the fact that Britain had suffered a major defeat. The backbench Conservative MP Leo Amery said Chamberlain's speech left the House in a restive and depressed, though not yet mutinous, state of mind. Amery believed that Chamberlain was "obviously satisfied with things as they stood" and, in the government camp, the mood was actually positive as they believed they were, in John Colville's words, "going to get away with it".