Norse funeral facts for kids

Norse funerals, or the burial customs of Viking Age North Germanic Norsemen (early medieval Scandinavians), are known both from archaeology and from historical accounts such as the Icelandic sagas and Old Norse poetry.

Throughout Scandinavia, there are many remaining tumuli in honour of Viking kings and chieftains, in addition to runestones and other memorials. Some of the most notable of them are at the Borre mound cemetery, in Norway, at Birka in Sweden, and Lindholm Høje and Jelling in Denmark.

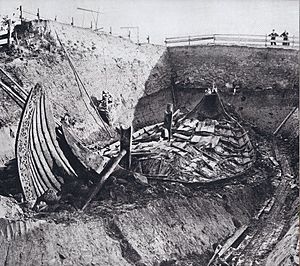

A prominent tradition is that of the ship burial, where the deceased was laid in a boat, or a stone ship, and given grave offerings in accordance with his earthly status and profession. Afterwards, piles of stone and soil were usually laid on top of the remains in order to create a tumulus. Additional practices included sacrifice or cremation, but the most common was to bury the departed with goods that denoted their social status.

Contents

Grave goods

It was common to leave gifts with the deceased. Both men and women received grave goods. A Norseman could also be buried with a loved one or house thrall, or cremated together on a funeral pyre. The amount and the value of the goods depended on which social group the dead person came from. It was important to bury the dead in the right way so that he could join the afterlife with the same social standing that he had had in life, and to avoid becoming a homeless soul that wandered eternally. The grave goods had to be subjected to the same treatment as the body, if they were to accompany the dead person to the afterlife.

The usual grave for a thrall was probably not much more than a hole in the ground. He was probably buried in such a way as to ensure both that he did not return to haunt his masters and that he could be of use to his masters after they died. Slaves were sometimes sacrificed to be useful in the next life. A free man was usually given weapons and equipment for riding. An artisan, such as a blacksmith, could receive his entire set of tools. Women were provided with their jewelry and often with tools for female and household activities. The most sumptuous Viking funeral discovered so far is the Oseberg Ship burial, which was for a woman (probably a queen or a priestess) who lived in the 9th century. These grave goods not only symbolized status, but also represented key moments or successes within the individuals life. Specific quantities of weapons like arrows could signify the extent of one's military prowess.

Some researchers have also proposed that grave goods served a practical social function within viking society. In the absence of rigid inheritance customs, or developed financial markets, the burial of grave goods may have served to mitigate potential intrafamilial inheritance conflicts. This has been offered to explain the predominance of illiquid assets in viking burials, as well the regional variation in grave contents.

The scope of grave goods varied throughout the viking diaspora, signifying the adaptability of viking funeral practices as they were influenced by these new cultures. While some factors such as animal themed ornamentation amongst jewelry and relics remained universal throughout the viking diaspora, some objects varied because of differing cultural influences, a common example being the integration of Christian iconography such as crosses in jewelry.

Funerary monuments

A Viking funeral could be a considerable expense, but the barrow and the grave goods were not considered to have been wasted. In addition to being a homage to the deceased, the barrow remained as a monument to the social position of the descendants. Especially powerful Norse clans could demonstrate their position through monumental grave fields. The Borre mound cemetery in Vestfold is for instance connected to the Yngling dynasty, and it had large tumuli that contained stone ships.

Jelling, in Denmark, is the largest royal memorial from the Viking Age and it was made by Harald Bluetooth in memory of his parents Gorm and Tyra, and in honour of himself. It was only one of the two large tumuli that contained a chamber tomb, but both barrows, the church and the two Jelling stones testify to how important it was to mark death ritually during the pagan era and the earliest Christian times.

On three locations in Scandinavia, there are large grave fields that were used by an entire community: Birka in Mälaren, Hedeby at Schleswig and Lindholm Høje at Ålborg. The graves at Lindholm Høje show a large variation in both shape and size. There are stone ships and there is a mix of graves that are triangular, quadrangular and circular. Such grave fields have been used during many generations and belong to village like settlements.

Rituals

The ritualistic practices of the viking diaspora were incredibly pliable as they adapted in response to temporal, cultural, and religious influences. While traces of pagan funeral practices remained a common thread, many of these practices shifted over time throughout these various regions, especially once Christianity began to rapidly influence the viking population. Recent discoveries at a burial site in Carlisle in the United Kingdom demonstrates a hybrid burial between pagan and Christian traditions, demonstrating the shift in ritual practice as the vikings began to slowly assimilate to these new regions.

Death has always been a critical moment for those bereaved, and consequently death is surrounded by taboo-like rules. Family life has to be reorganized and in order to master such transitions, people use rites. The ceremonies are transitional rites that are intended to give the deceased peace in his or her new situation at the same time as they provide strength for the bereaved to carry on with their lives.

Despite the warlike customs of the Vikings, there was an element of fear surrounding death and what belonged to it. Norse folklore includes spirits of the dead and undead creatures such as revenants and draugr.

The funeral ritual could be drawn out for days, in order to accommodate the time needed to complete the grave. These practices could include prolonged episodes of feasting and drinking, music, songs and chants, visionary experiences, human and animal sacrifice. Eyewitness accounts even credit women as having key roles in these ritualistic practices, serving as almost the director of the funeral. These performance styled funeral rituals tended to occur within similar places in order to create a spatial association of ritualistic practice to the land for the community. Places like lakes, clearings, or even around large trees could serve as the central location of these rituals. Ultimately, funeral practices were not just a singular act of burying one person. The scope of these practices tended to exceed the burying of just one individual.

Ship burials

The ship burial was a funeral practice traditionally reserved for individuals of high honor. The practice includes the burying of the individual within a ship, using the ship to contain the departed and their grave goods. These grave goods featured decorative ornamentation that far exceeded the extravagance of traditional burials. Additionally, animal remains such as oxen or horses tended to be buried within the ship. Ship burials can also include the dead being buried in the ground and then on top of the grave, stones are placed in the shape of a ship or a runestone placed on the grave with a ship or scene with a ship carved into the stone.

The ships tended to be ships of pleasure rather than ships utilized for travel or attack. Some ships were potentially chartered for the sake of a ship burial, especially considered they were designed without some necessary features like seats.

Cremation

It was common to cremate the dead and burn the grave offerings on a pyre. Only some incinerated fragments of metal and of animal and human bones would remain. The pyre was constructed to make the pillar of smoke as massive as possible, in order to elevate the deceased to the afterlife.

Funeral ale and the passing of inheritance

On the seventh day after the person had died, people celebrated the sjaund (the word both for the funeral ale and the feast). The funeral ale was a way of socially demarcating the case of death. It was only after drinking the funeral ale that the heirs could rightfully claim their inheritance. If the deceased were a widow or the master of the homestead, the rightful heir could assume the high seat and thereby mark the shift in authority.

Several of the large runestones in Scandinavia notify of an inheritance, such as the Hillersjö stone, which explains how a lady came to inherit the property of not only her children but also her grandchildren and the Högby Runestone, which tells that a girl was the sole heir after the death of all her uncles. They are important proprietary documents from a time when legal decisions were not yet put to paper. One interpretation of the Tune Runestone from Østfold suggests that the long runic inscription deals with the funeral ale in honor of the master of a household and that it declares three daughters to be the rightful heirs. It is dated to the 5th century and is, consequently, the oldest legal document from Scandinavia that addresses a female's right to inheritance.

See also

- Death in Norse paganism

- Burial in Anglo-Saxon England