Norman Heathcote facts for kids

John Norman Heathcote (21 June 1863 – 16 July 1946) was a British author, watercolourist and photographer, who wrote the book St Kilda, published in 1900, about the Scottish Hebridean archipelago of St Kilda.

Family and biography

Norman Heathcote was the second child and eldest son of John Moyer Heathcote and Louisa Cecilia MacLeod who married in 1860. His father (whose mother was the youngest daughter of Nicholas Ridley-Colborne, 1st Baron Colborne) was a barrister and distinguished amateur player of real tennis. His mother was the eldest child of Norman Macleod, 25th chief of Clan Macleod. As a child Norman lived in London, Brighton and at Conington Castle.

Heathcote was born in 1863 and attended Eton College and then Trinity College, Cambridge from 1882, where he took a BA degree in 1885. He became a Justice of the Peace in 1906 and was High Sheriff of Huntingdonshire in 1917/18. On his father's death in 1912, he inherited Conington Castle, Conington, Huntingdonshire with its estate of over 7,000 acres (2,800 ha) and lived there for many years. He also inherited the lordship of the manor of Steeple Gidding which he sold to a Mr Tower in 1915. In 1933 he owned a steam yacht called Ketch.

St Kilda

St Kilda

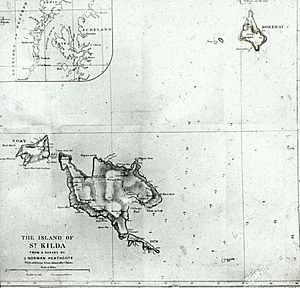

In 1898 and again in 1899 Heathcote visited the archipelago with his sister, Evelyn. At that time St Kilda was owned by his uncle, Reginald MacLeod of MacLeod. He went on to write a book about the islands which was published in London by Longmans, Green in 1900 and reprinted in 1985. It included eighty of his own illustrations – photographs (taken with a handheld camera), sketches, paintings and a map. He was the first to record several bird species on the islands. The book deals with the people of St Kilda, their history and customs; the wildlife (particularly birds) and his and his sister's experiences boating and climbing with the St Kildans.

In 1898 Heathcote and his sister arrived after a four-hour voyage on the Martin Orme steamer SS Dunara Castle for a stay of ten days. Dunara and the McCallum steamer Hebrides between them visited about once a fortnight but only in the three summer months. There were about twenty visitors, some were tourists but others had arrived to start building the new schoolhouse – until that time lessons had been given in the kirk. In 1898 Evelyn laid the foundation stone and by the time of their 1899 visit the school had been completed and the kirk had been completely renovated. The resident population numbered seventy and most spoke only Gaelic although the children were taught English at school.

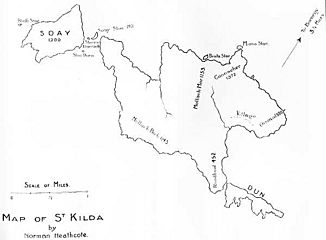

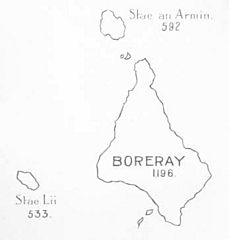

In 1899 their visit lasted two months and in July Heathcote and Evelyn were rowed to Boreray and from there they together climbed the sea stack Stac Lee. He wrote that Stac Lee was "not a difficult climb" and that, before Evelyn, two other women had reached the summit. However, after exploring Boreray and setting off to row back to the main island, Hirta, the weather deteriorated and they were forced to spend the night in their boat, sheltering in a sea cave on Boreray. When he visited Stac Levenish he was told he was the first person who was not a St Kildan ever to have been there. Unable to board the boat again, he had to climb the stack so as to descend on the other side where the boat could be in more sheltered water. He considered the most difficult stack to climb was Stac Biorach, saying that Richard Manliffe Barrington was the only non-St Kildan to have climbed it.

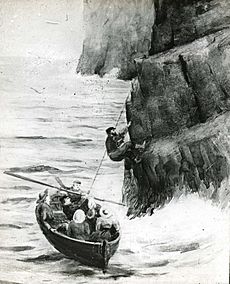

Journal articles

He also published a paper "A Map of St Kilda" in the Geographical Journal of 1900 describing his surveying methods in producing the map that was included in the St Kilda book. Except at Village Bay on Hirta it is difficult to climb down to the shore and indeed from the top of the cliffs it is often impossible to conveniently see the coast. At Soay and Boreray he did not even try to get his theodolite ashore. A year later in "Climbing in St Kilda" in the Scottish Mountaineering Club Journal he gave an account of his experiences climbing. He gave details of climbing Stac Lee saying it was "comparatively easy" although getting ashore onto the stack was "a most appalling undertaking" involving jumping ashore and climbing an overhanging cliff covered in slippery seaweed to a stanchion twenty feet (six metres) above sea level. He recommended taking off boots and climbing in socks.

- SMCJ (1901) maps of St Kilda (not to same scale)